Art

Why Manet’s Empathetic Painting of a Parisian Prostitute Still Resonates Today

Édouard Manet, Nana, 1877. Kunsthalle Hamburg. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

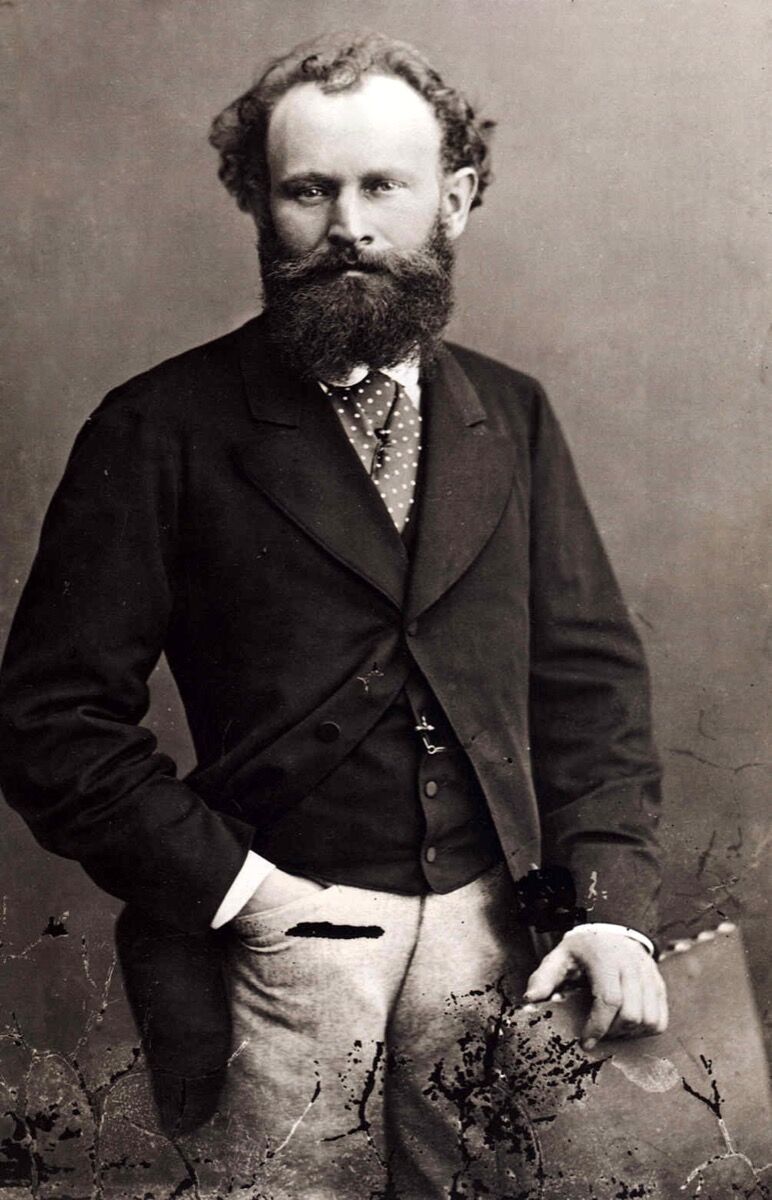

Nadar, Portrait of Édouard Manet, ca. 1867-70. Photo via Wikimedia Comm

Nineteenth-century Paris was obsessed with prostitutes. Courtesans (as the expensive mistresses of politicians, businessmen, and princes were known) rose from poverty to enjoy the glitz and glamour of the city’s wealthiest elite using what can only be called sheer hustle. They commanded the era’s imagination, not only with their luxurious apartments and opulent jewels, but with the power they exerted over some of the most influential men of the time.

The artists of the era were similarly preoccupied: French painting, drawing, and sculpture from the time is replete with images of prostitutes. “Painters suddenly decided to paint what was around them, what they were actually seeing,” historian Anka Muhlstein told Artsy. “So instead of painting allegories or historical things, they would paint what they encountered in everyday life.”

While these artists may have focused on the same subject, they went about it in very different ways.

depicted the more socially palatable world of theater and dance, a sexually murky sphere where ballerinas and actresses operated as prostitutes on the side. His paintings weren’t monumental; the subjects rarely face the viewer, looking more like the unassuming and impoverished dancers they were.

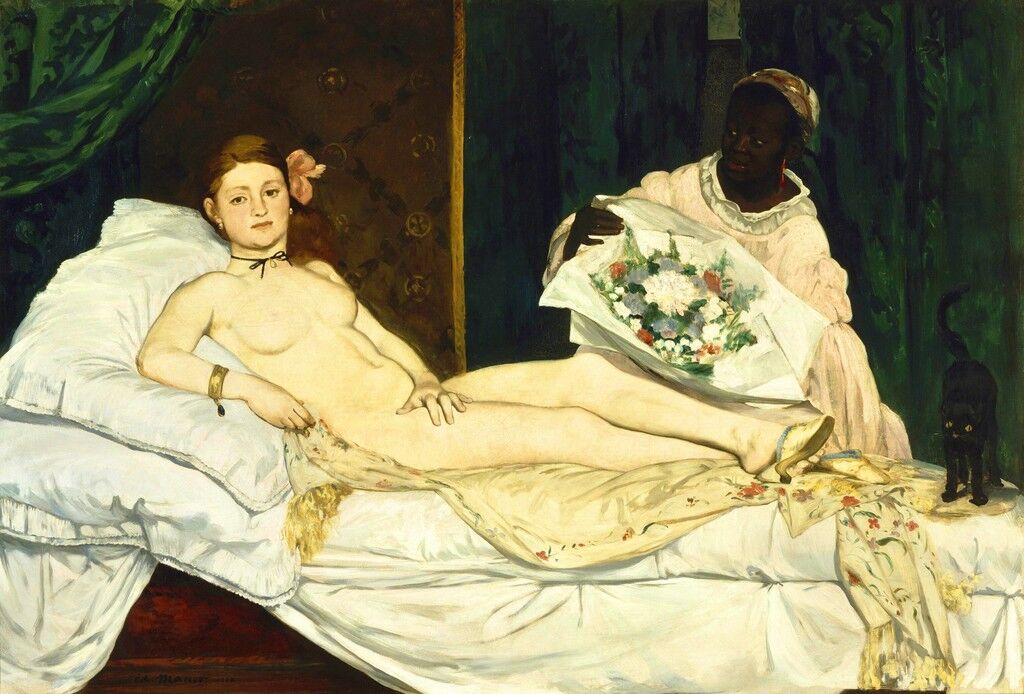

, on the other hand, favored canvases too large to ignore. His renditions of prostitutes, portrayed with refinement and femininity, stare boldly out at the viewer. Case in point: his 1877 painting Nana.

This piece is a nearly life-size work of playful homage to the courtesans of the era. Nana, the prostitute, is the star of the scene: Her body, from blonde head to delicately pointed toe, fills the entire central third of the painting. Her presence is bold, almost imposing; she overshadows her male customer, cut in half by the frame and blending into the background with his dark suit. With a little half-smile on her lips, she stares directly out at the viewer, implicating them in whatever illicit scene they have stumbled onto. Rather than the typical societal shame associated with prostitution, Nana appears both open and proud. She is a woman who is aware of her power and how to use it.

Although today it hangs proudly in Hamburg’s Kunsthalle, when the painting was first shown, the reception was far from friendly. At the time, the art world was more comfortable with painted nudes featuring a heavy dose of

. It certainly wasn’t used to seeing a modern-day courtesan portrayed as a “pretty girl, practically winking at you, practically making fun of the old man with his top hat,” notes Muhlstein, whose book The Pen and the Brush explores the relationship between 19th-century French painters and writers. “The fact that she looked sympathetic, she looked appealing.…She looks extremely pleased with herself, and I think that probably was shocking for people.” The French Academic Salon, the only real path to artistic success in 19th-century France, rejected the painting from its 1877 exhibition.

Manet nevertheless found a way to display the work. In lieu of the salon, he hung it in the window of a trinket shop on the Boulevard des Capucines, one of Paris’s main thoroughfares. The painting became a popular attraction, toying with the visual pun of a painted prostitute displayed on the same street real-life prostitutes would frequent at night.

Manet was close friends with the writer Émile Zola; both lived in the Montmartre neighborhood of Paris, where they traded ideas and inspiration with other artists such as Degas and

. (The group dubbed themselves the Batignolles and would eventually form the

.) In dialogue with Manet’s painting, Zola went on to write a book about the fictional prostitute’s rise to fame. Completed in 1880, it was also titled Nana.

Zola’s novel stands in great contrast to Manet’s painting. Where Manet was cheeky, Zola was moralizing; where Manet was observant, Zola was judgmental. The writer describes Nana at one point as “the Beast of the Scriptures,” whereas “the painting is really the epitome of art without moral dimension,” Muhlstein notes. “Manet just shows something, he doesn’t judge.”

Today, Zola’s Nana is read mostly as a clunky period piece. It’s hard to take his outrage about the prostitute seriously. Perhaps one reason Manet’s image resonates more strongly today is because of his sense of empathy—he allowed Nana to be both a powerful woman and a prostitute, without assigning fear to that concept in the way that Zola did. He wasn’t afraid to attribute the figure of Nana with real societal power.

And, as a result, “prostitutes appeared as real people,” says Muhlstein. “If you take the example of Nana, there you have a young prostitute, a courtesan, looking at you straight in the face. She’s a person—you can’t just brush her aside as you would if you encountered a streetwalker. Suddenly, you’re face to face with her.”

No comments:

Post a Comment