The Art Angle

The Art Angle Podcast: How the Medicis Became Art History’s First Influencers

This week, art historian Eleanor Heartney joins Ben Davis to discuss the influential Italian family.

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join host Andrew Goldstein every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more with input from our own writers and editors as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

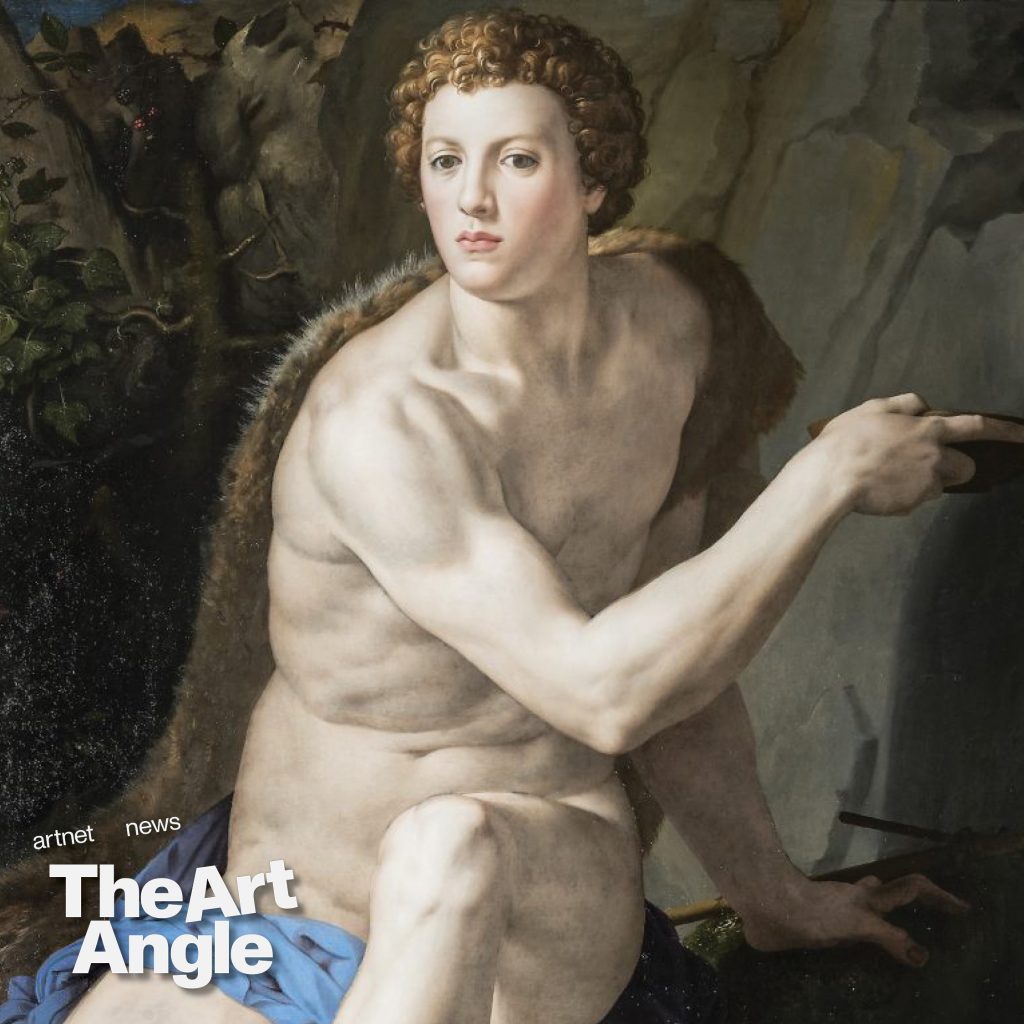

If you’re a fan of Italian Renaissance art and you’re in New York, right now the Metropolitan Museum of Art has a treat for you. It’s called “The Medici: Portraits and Politics, 1520-1570” and it offers a spectacular sampling of 90 works of art from Florence’s 16th century. But there’s a twist.

It probably comes as no surprise to anyone that Italian Renaissance art was connected to the most powerful people in society.

Still, even today if you call someone a Medici, you probably mean to say that they are a visionary patron of the arts, when it could just as well mean that you are calling them a ruthless oligarch. This exhibition actually tries to show how some of the classics of art in this time were not just works of beauty, which the Medici happened to do on the side, but part of a carefully calibrated political PR campaign that deliberately shaped how the public sees this family in their time and up to our own.

Art historian Eleanor Heartney wrote an essay for Artnet News, looking at the Met show and the world of the Medici, asking how the history behind the art changes how we look at what the Metropolitan Museum accurately advertises as some of the most famous European paintings of all time.

This week on the podcast, Heartney sits down with Artnet News’s Ben Davis to discuss the influential Italian family.

Listen to Other Episodes:

The Art Angle Podcast: How Two Painters Helped Spark the Modern Conservation Movement

The Art Angle Podcast: The Hunter Biden Controversy, Explained

The Art Angle Podcast (Re-Air): How Photographer Dawoud Bey Makes Black America Visible

The Art Angle Podcast: Tyler Mitchell and Helen Molesworth on Why Great Art Requires Trust

The Art Angle Podcast: How High-Tech Van Gogh Became the Biggest Art Phenomenon Ever

The Art Angle Podcast: How Much Money Do Art Dealers Actually Make?

The Art Angle Podcast: What Does the Sci-Fi Art Fair of the Future Look Like?

The Art Angle Podcast: How Kenny Schachter Became an NFT Evangelist Overnight

The Art Angle Podcast: How Breonna Taylor’s Life Inspired an Unforgettable Museum Exhibition

Shattering the Glass Ceiling: Art Dealer Mariane Ibrahim on the Power of the Right Relationships

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: