Josef Koudelka: The Black Triangle

Josef Koudelka’s powerful black and white panoramas of the Black Triangle bear witness to the environmental destruction of this Czech border region

Josef Koudelka Around a coal-mine. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1993. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka A former mining area. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1992. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

"Man is not an omniscient master of the planet who can get away with doing whatever he likes and whatever may suit him at the moment"

- Václav Havel

Josef Koudelka A new rubbish disposal site. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1991. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka Coal mining. The Black Triangle. Czech Republic. 1993. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka An area in which many companies worked: H. Göring Werke in 1943, the Stalin Firms in 1945, the Chemical Firms of the Soviet-Czechoslovakian Friendship in 1954 and Chemopetrol in 1990. The Black Tri (...)

License |

Josef Koudelka A brown coal mine. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1991. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka An effort at recultivation. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1992. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka The Bilina riverbed has been dug-up and replaced 65 times as a result of coal mining. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1993. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka Coal mining. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1992. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

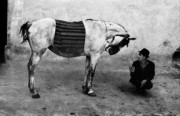

Josef Koudelka The Black Triangle. Czech Republic. 1992. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka The landscape has been completely ruined by coal mining. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1991. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka Coal mining. The Black Triangle, Czech Republic. 1992. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |