Visual Culture

The Story behind the Surreal Photograph of Salvador Dalí and Three Flying Cats

Before photographer

and

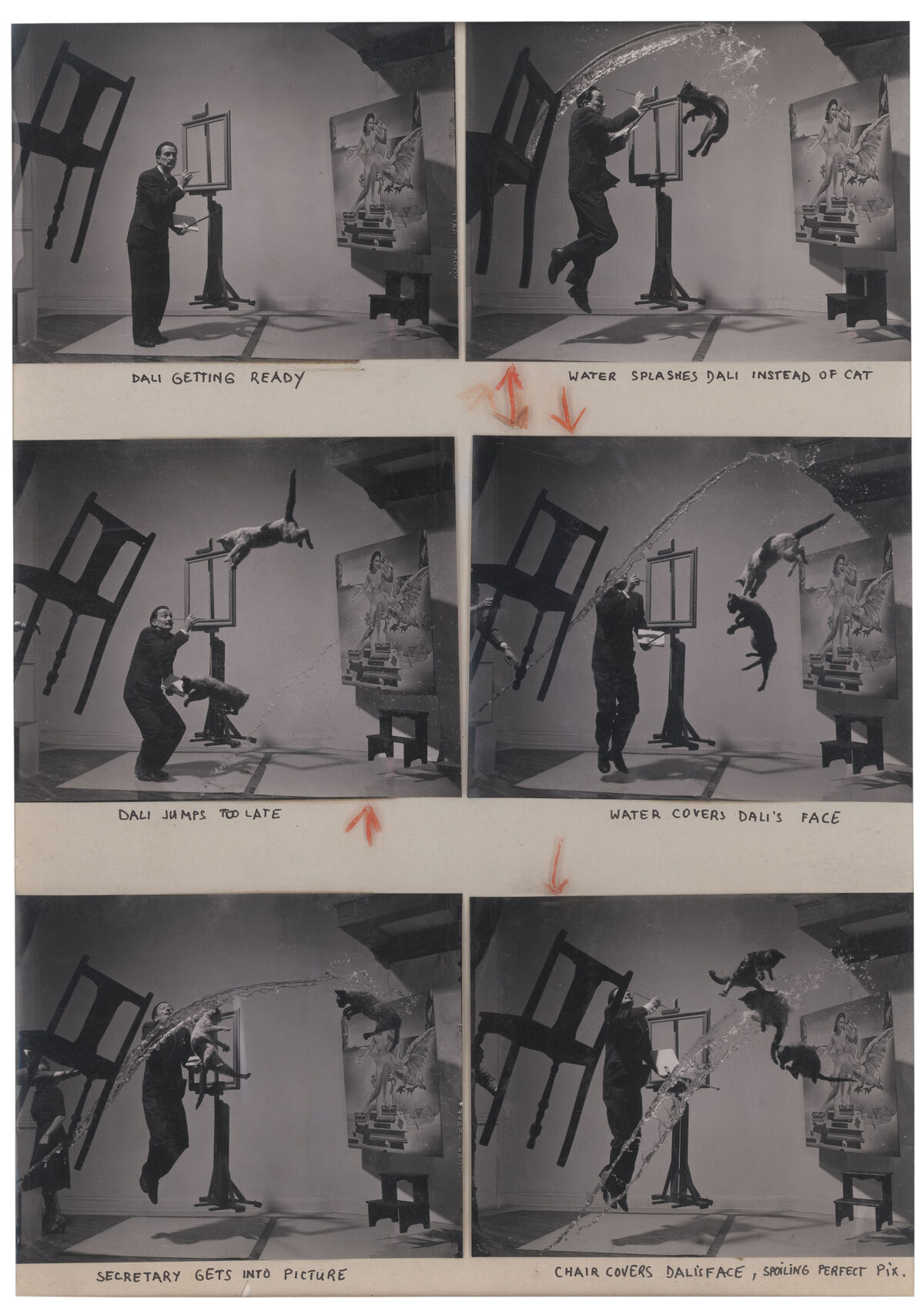

settled on the idea of tossing three cats into the air for the photograph Dalí Atomicus (1948), the Spanish artist suggested they blow up a duck using dynamite. Considering it took 26 attempts to pull off the picture of a levitating Dalí in a chaotic airborne scene, Halsman’s insistence against the first idea was decidedly the best course of action.

Halsman, a mid-century portrait photographer, sought to lift the veil on his subjects, however briefly, to reveal their innermost being. “A true photographer wants to try to capture the real essence of a human being,” he once famously said. But capturing the essence of Dalí was a complex task. Over nearly four decades, Halsman photographed the artist on many occasions, spurring the most iconic black-and-white portraits of the Surrealist.

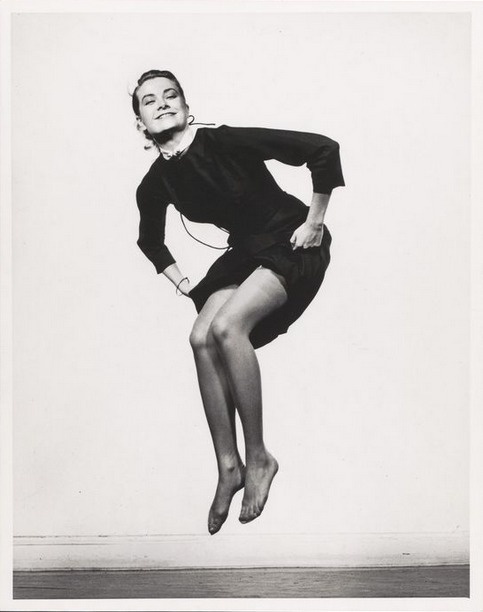

Dalí Atomicus was an early example of the practice Halsman called “jumpology.” To capture the true spirit of his subjects—primarily celebrities and public figures who were accustomed to having a lens trained on them—he began asking them to take a jump after each photo session. “When you ask a person to jump, his attention is mostly directed toward the act of jumping and the mask falls so that the real person appears,” he once explained.

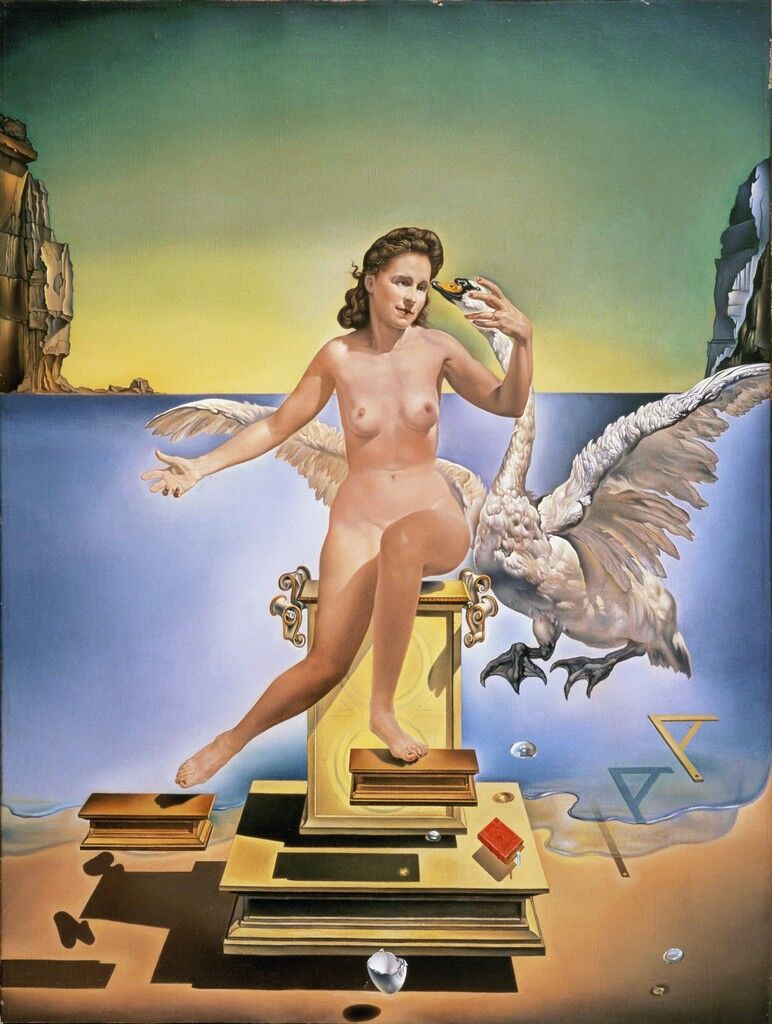

Salvador Dalí

Atomic Leda, 1949

Teatro Museo Dalí, Figueres

But years before he convinced Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Richard Nixon, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor to each take a leap of faith, he staged the outlandish (and, ultimately, duckless) shoot of Dalí. The artist appears suspended in the air amid three flying cats, a stream of water, and floating furniture.

When Dalí and Halsman became close friends in the 1940s, Halsman had experienced a great deal of hardship in his life. The photographer, born in Riga in 1906, was falsely convicted of killing his father in 1928, and he was sentenced to four years in prison, where he contracted tuberculosis. He was released two years early, following a successful campaign led by his sister, Liouba, which included a letter by German physicist Albert Einstein. Einstein would come to Halsman’s aid again in 1940 after the photographer had established his career in Paris, obtaining a U.S. visa for Halsman in order to help him escape the Nazi invasion of France. (Halsman’s deeply emotional portrait of Einstein, taken seven years later, would become one of his most famous works.)

4 Images

View Slideshow

The first portrait that Halsman took of Dalí in 1941, atop a New York roof, cemented their friendship. It led to bodies of work such as the absurdist (and aptly titled) book Dalí’s Mustache (1954), featuring 36 views of his collaborator’s famous waxed mustache. Other compositions, which placed Dalí in uncanny worlds not unlike those of his own imagination, took time and painstaking detail to pull off. In Popcorn Nude (1949), Dalí thrusts his leg into a high kick as popcorn kernels and baguettes explode around a nude model. And to create In Voluptas Mors (1951), it reportedly took Halsman three hours to arrange the women’s bodies so that they formed the illusion of a skull.

Dalí Atomicus also required intense preparation. Halsman drew his inspiration from the artist’s painting Leda Atomica (1949)—the work, which Dalí began in 1945, is pictured in the back-right of the scene. But unlike the painting, he wished to have all elements of the photograph hang in the balance.

Philippe Halsman, Dali Atomicus, 1948. © Philippe Halsman/Magnum Photos.

The original, unretouched version of the photo reveals its secrets: An assistant held up the chair on the left side of the frame, wires suspended the easel and the painting, and the footstool was propped up off the floor. But there was no hidden trick to the flying cats or the stream of water. For each take, Halsman’s assistants—including his wife, Yvonne, and one of his daughters, Irene—tossed the cats and the contents of a full bucket across the frame. After each attempt, Halsman developed and printed the film while Irene herded and dried off the cats. The rejected photographs had notes such as “Water splashes Dalí instead of cat” and “Secretary gets into picture.”

When Halsman was finally satisfied with the composition, Dalí added a finishing touch to the printed photograph: the swirls of paint that appear on the easel. The final image was published in Life magazine. (Halsman, incidentally, holds the record for the most Life covers ever shot—101 in total.)

Though they were two creative minds at the height of their careers, the relationship between Dalí and Halsman was never competitive, as Irene Halsman explained in a 2016 video about the photograph for Time. “Dalí never really wanted to photograph; Philippe never really wanted to pick up a paintbrush,” she said. “But together, they collaborated and made the most outrageous pictures.”

Jacqui Palumbo is Artsy’s Visual Culture Editor.