| The First Art Newspaper on the Net |   | Established in 1996 | Monday, October 19, 2020 |

|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

| The First Art Newspaper on the Net |   | Established in 1996 | Monday, October 19, 2020 |

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

|

A work by Andreas Gursky sold in 2011 for more than the combined auction sales of every contemporary German photographer in the first half of 2020.

For more than a decade, their massive images of stock exchanges, Brutalist facades, and opera houses were a must-have for top collectors. Photographs by members of the Düsseldorf School—a group of German photographers that includes Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, and Thomas Ruff—were snapped up by the likes of mega-collector Eli Broad, actor Leonardo DiCaprio, and gas-company billionaire Leonid Mikhelson. One London hedge fund reportedly purchased five of Gursky’s stock-exchange photos to decorate its trading floor.

These days, however, the supersize works are considerably less in demand. Back in 2011, a single print by Andreas Gursky sold for more than the cost of every contemporary German photographer’s work brought in at auction in the first half of 2020—combined.

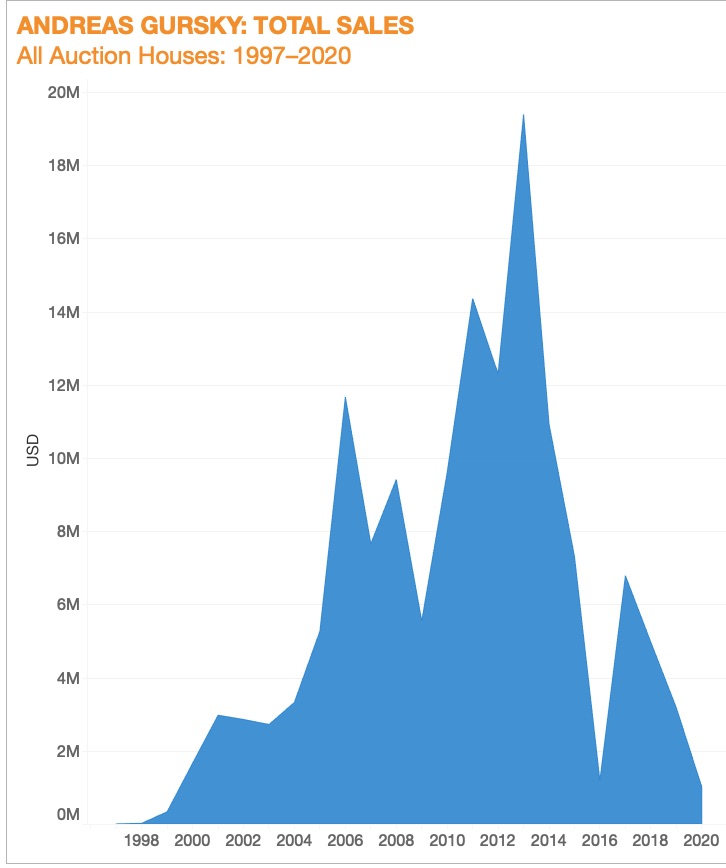

In 2011, work by contemporary German photographers generated a combined $21 million at auction. Last year, that total fell by almost 50 percent, to $10.6 million, according to the Artnet Price Database. In the first half of this year, sales by the group (defined as German photographers born after 1945) shrank even more dramatically, bringing in just $3.9 million at auction.

Andreas Gursky, Rhein II (1999). Image courtesy Christie’s.

The Düsseldorf School artists studied under influential photography duo Bernd and Hilla Becher for years before putting their individual conceptual spins on the medium and (literally) blowing it up with the help of digital technology. In the late aughts and early 2010s, the market couldn’t get enough.

“All of these artists appeared around the same time,” the art advisor Todd Levin tells Artnet News. “Advancements in printing techniques allowed the creation of photographs on a much larger, cinematic scale. It provided a new way of thinking about photography and what it could be.”

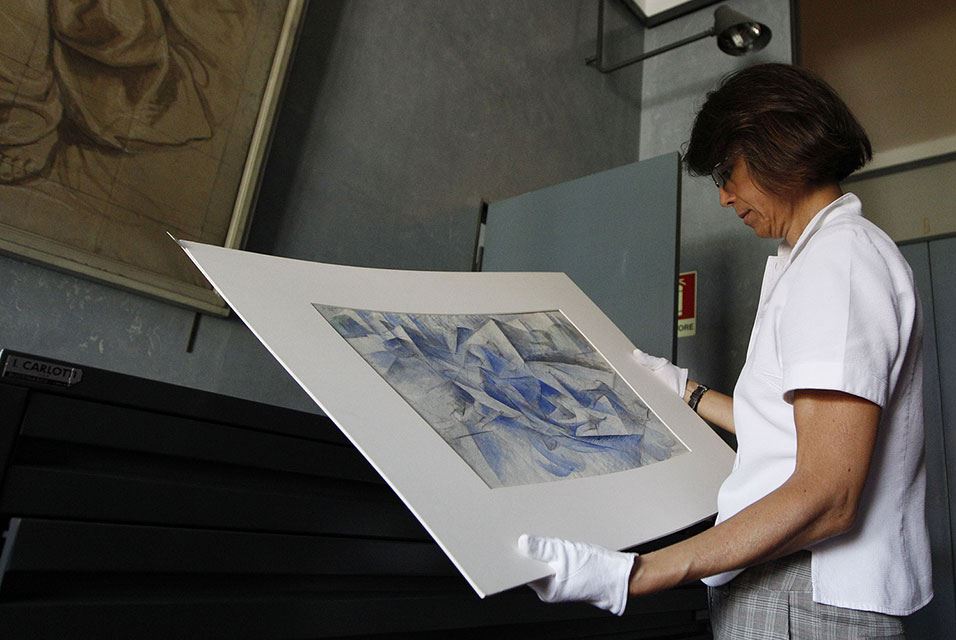

Of the three best-known members of the school, Gursky is by far the most expensive—and has also seen his auction prices tumble most dramatically. In 2011, his average work sold at auction for almost $600,000. This year, that figure tumbled more than 85 percent, to just $84,655.

Nearly nine years ago, Rhein II (1999), a wide-angled view of the riverbank, realized $4.3 million, setting the record for the most expensive photograph ever sold at auction. (The buyer for that work, it should be noted, was the now-jailed art dealer Inigo Philbrick.)

Gursky’s second-highest auction price, $3.3 million, was set in 2007 for his oft-reproduced image of a 99-cent store. But the artist—whose work broke the $1 million mark at auction at least once a year from 2006 to 2017 (with the exception of post-crash 2009)—hasn’t passed the seven-figure threshold in three years.

Ruff, who is known for his oversize passport-style portraits of young people, has experienced a similar, though less dramatic, trajectory, with his average auction price falling 45 percent between 2011 ($28,035) and the first half of 2020 ($15,978). Struth, celebrated for his images of tourists dwarfed by cultural wonders, saw his average price rise just over eight percent during this same period, while his total auction sales fell 52 percent.

There is no shortage of critical acclaim, exposure, or scholarly attention for any of these artists. Berlin and Los Angeles gallery Sprüth Magers is presenting a show of Gursky’s first new work in nearly three years in Germany, in addition to an online show titled “Space Is Time” (through November 14). In December, the German photographer will be the subject of a major exhibition at the Museum der bildenden Künste in Leipzig.

Struth, meanwhile, had a show of roughly 130 works at the Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain at the start of 2019, and Ruff was the subject of a solo exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2017. A solo presentation of 30 years’ worth of his work is on view at K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, while another one-man show is due to open at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in 2021.

Thomas Ruff, Jpeg pt01 (2006). Image courtesy Christie’s.

How can three artists with impeccable collectors, museum presence, and curatorial attention fall into such a rut on the auction block? Experts attribute the dynamic to a combination of factors, starting with oversupply.

As more and more work surfaced on the market, demand was eventually met—and buyers became picky. Most top photographers might put out eight to 12 images a year, typically in editions of six to 10, which means a ballooning supply year over year. The largest, most sought-after works by the Düsseldorf School artists come in editions of four to eight. Still, Todd Levin says, “after serious private and institutional collectors have accessed those works they deem crucial, the market tilts towards oversupply.”

Darius Himes, international head of photographs at Christie’s, says the buoyant market for these photographers in the early 2010s was the result of a perfect storm.

“The top prices for those relatively few works were achieved in the marketplace at a moment when the attention by major museum exhibitions coincided with [the artists’] entrance into the auction market within contemporary art departments” as opposed to photography auctions, Himes notes. Presenting their work in a contemporary art context was important at a time when top collectors were already accustomed to shelling out far more than $1 million for a blue-chip trophy.

As for Rhein II, the record-setting Gursky photograph, many of its editions are in institutions, driving up the value of the example that appeared on the market. “Though photographic works are often editioned, the supply is not limitless and therefore a ‘market’ for an artist can seemingly go quiet after a flurry of public visibility simply because the supply wanes,” Himes says.

Another huge factor, the experts point out, is practical. These works are big. “The sheer scale is a tremendous limiting factor that, at first, people were willing to put up with because they were sincerely interested in the work,” Levin says. Unlike a painting, these images cannot be rolled or compacted for moving.

“Large-scale photography, when framed or backed with some of the latest aluminum or polymer backings, are not forgiving like canvases,” says Jonathan Schwartz, president of storage and shipping company Atelier 4.

Tales abound of the incredible logistical challenges that come with moving these works from trucks to hallways to Park Avenue apartment buildings. There have been instances, Levin recalls, of art handlers being unable to fit them into elevators, opting instead to slide them on top for the ride.

Source: Artnet Analytics

Gursky and Ruff’s dealers, Monika Sprüth and Philomene Magers, caution that auction prices are just one part of the picture. A representative of Marian Goodman Gallery, which represents Thomas Struth, says the gallery does not comment on market-related issues, though sources say his works range in price on the primary market from $25,000 for a small example to $250,000 for a museum-quality piece.

“The interest in Andreas’ works has been very steady over the years,” Sprüth and Magers say of Gursky, with whom they have worked since 1993. Since he only creates a few works per year, “the demand is significantly higher than the supply.”

Installation of Andreas Gursky’s current show at Sprüth Magers Gallery in Berlin. Image courtesy Sprüth Magers.

In addition to the allure of famous images like Rhein II, 99 Cent II, and the various stock exchanges, Gursky’s new work depicts a cruise ship under construction, an image that has “gained an extra level of meaning and significance due to the current global situation,” the gallerists say. New works by the artist are priced at up to €1 million ($1.2 million).

Meanwhile, Ruff’s new series is priced at €45,000 ($52,000) for flower.s (2018), produced in an edition of six, and €85,000 ($99,900) for tableau chinois (2019), in an edition of four. Ruff’s auction record is lower than his two peers: $240,000 for Jpeg pt01 (2006), sold at Christie’s in 2017.

Sprüth Magers has been working with Ruff since 2016 and the dealers say they have seen increased demand for the artist’s “Stars,” “Substrates,” and “Photograms” series in particular over the past few years.

Thomas Ruff, Substrat 32II (2007). Image courtesy Sprüth Magers.

Phillips head of photographs Sarah Krueger concedes that while the primary market for these artists is solid, the secondary market “is quite selective, so you won’t necessarily see a great deal of these at auction in any one season.” When they do appear, she says, “and are priced to achieve an accurate representation of the market, collectors remain committed to bidding and are willing to overcome any logistical issues that arise when purchasing works of such monumental scale.”

She notes that in 2016, Gursky’s Athens (1995), a work that is over 12 feet wide, sold for $400,000 against a low estimate of $250,000. Another work by the artist, São Paulo, Sé (2002), offered at Phillips on October 14 with an estimate of $400,000 to $600,000, failed to sell online, but Phillips noted it may sell privately.

In a 2018 New York Times profile, Gursky seemed more than comfortable with the arc of his career. “Asked if his fame and fortune caused him discomfort, Mr. Gursky laughed. Money had, of course, changed his life, he said, because he could afford to travel wherever he wanted.”

“I’m just interested in making images,” the photographer said.

It looks like you're using an ad blocker, which may make our news articles disappear from your browser.

artnet News relies on advertising revenue, so please disable your ad blocker or whitelist our site.

To do so, simply click the Ad Block icon, usually located on the upper-right corner of your browser. Follow the prompts from there.

|

|

|---|

The surge in online viewing rooms is poised to change the art industry's uneasy relationship to price transparency.

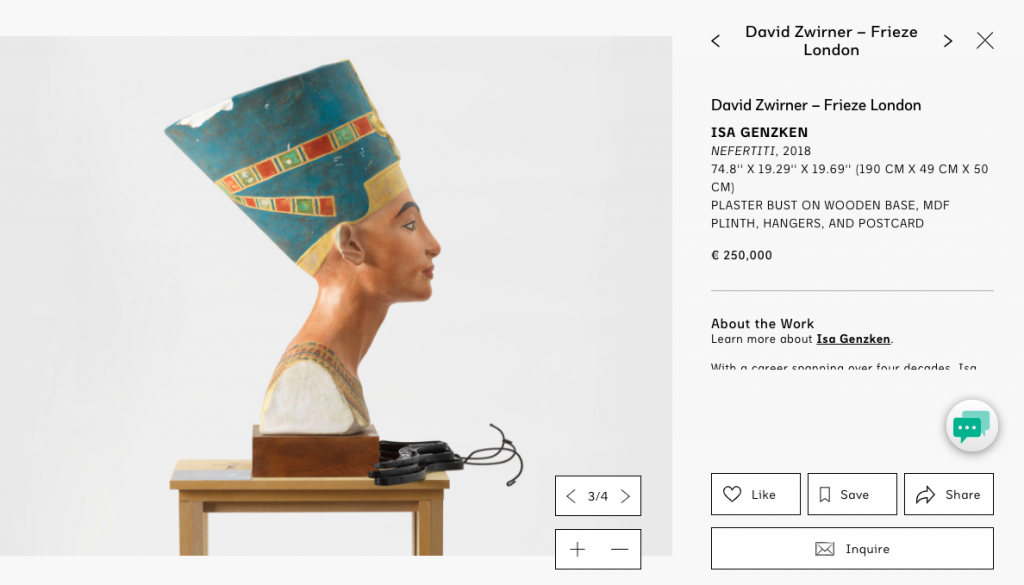

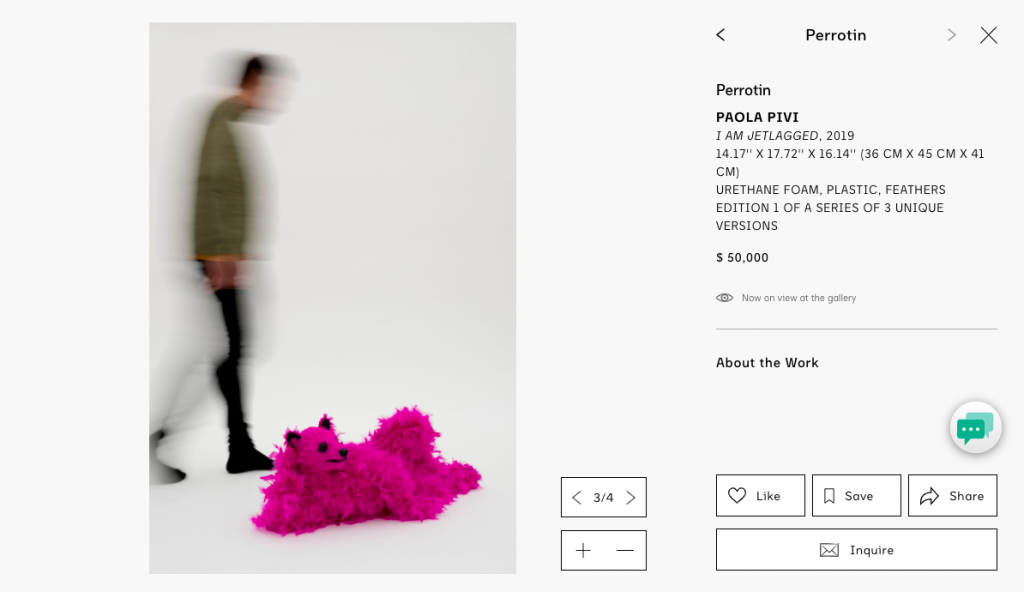

As collectors clicked through Frieze London’s first online-only fair last week, they found plenty of similarities to fairs of years past. David Zwirner was there with photographs by Wolfgang Tillmans and William Eggleston; Pace offered sculptures by Lynda Benglis; Perrotin had works by JR and Daniel Arsham.

But there was one key difference: Almost across the board, prices were clearly listed.

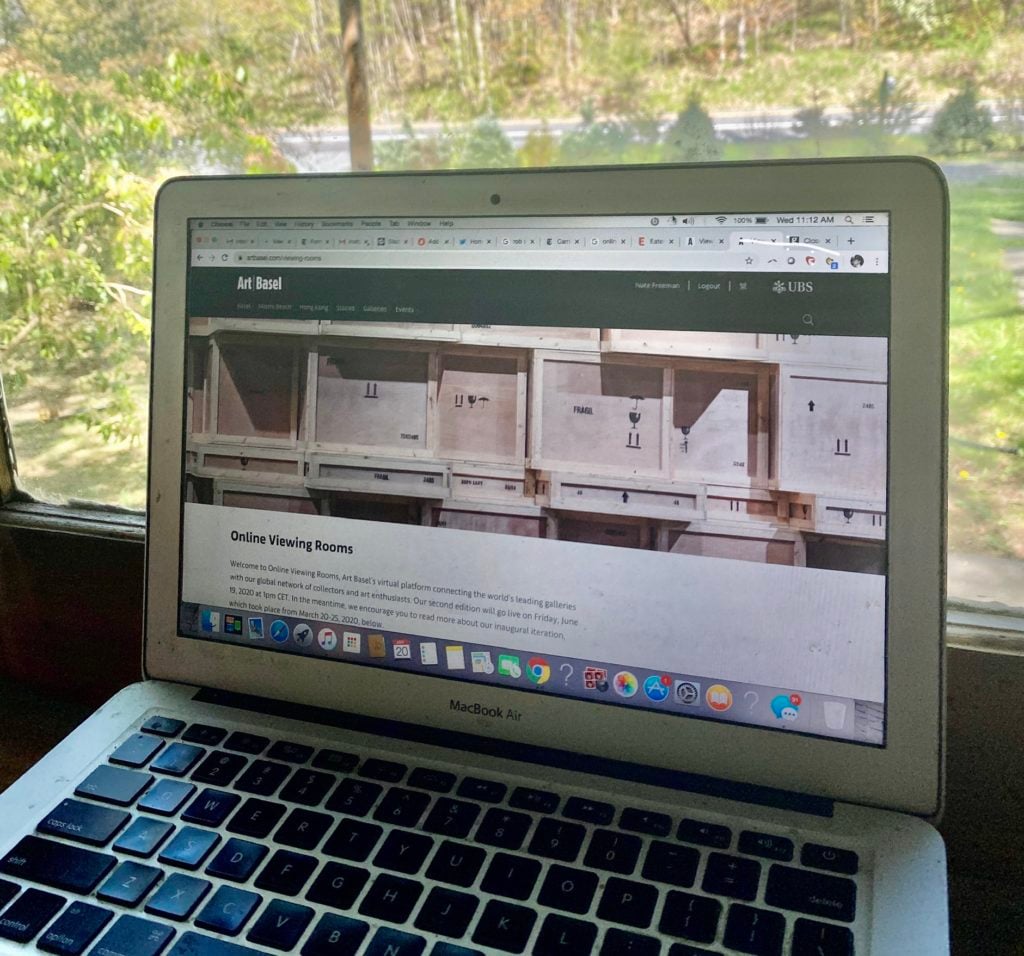

The shutdown that rippled across the globe in the first half of 2020 accelerated the development of online viewing rooms and, with them, pricing in the notoriously opaque art market has grown markedly more transparent. Galleries at Art Basel that never would have posted prices on their booth walls suddenly opted to include them in their online “rooms” at the digital edition of the Hong Kong fair in March—the kind of one-glance transparency that buyers today expect when shopping online.

David Zwirner’s viewing room as part of Frieze London 2020. Courtesy Frieze.

Around the same time, David Zwirner launched an online sales platform to sell works by smaller New York galleries that were struggling to stay afloat amid the lockdown. They too tended to list prices.

“Having a price visible to all audiences, not just VIP collectors, who were the only ones privy to that information in the past, moves the art world into a positive and more open direction,” Elena Soboleva, director of online sales at Zwirner, tells Artnet News.

Thaddaeus Ropac, who runs galleries in Paris, Salzburg, and London, is the rare dealer who has long displayed an openness toward disclosing prices. “At the fairs, we are happy to tell anyone interested and this conversational aspect is part of what makes the experience so personal and social,” he says. But the shift online has pushed him even further toward transparency. “With prices visible on our online viewing room we found that incoming inquiries tended to be serious clients with a definite interest in the works available and that new collectors or those unfamiliar with an artist were able to inquire with confidence.”

Technically, galleries—at least in the art market capital of New York—are supposed to post prices just like any other retail store. Since the mid-1960s, New York City’s consumer protection and regulatory agencies have legally required galleries to conspicuously post prices on their exhibition floors. But art dealers ignored the law and, in 1988, the agencies vowed once again to enforce it in order to combat the “price manipulations” that the city’s department of consumer affairs said were “endemic” to the art market.

Perrotin’s viewing room at Frieze London 2020. Courtesy of Frieze.

For the next three decades, however, galleries carried on flouting the rules—because they had significant business incentives to do so. For one thing, a gallerist may not want to do further harm to an artist whose prices are flagging by displaying the markdowns. They may also not want to disclose prices to competitors, or reveal the preferential prices they give to certain loyal or VIP collectors.

“Not displaying prices can create room to maneuver when a client walks into the gallery,” says Olav Velthuis, a sociologist of the arts at the University of Amsterdam. “Depending on the dealer’s assessment of his willingness to pay, the price can be adjusted upward or downward.”

Bucking convention might also delegitimize a gallery in the eyes of collectors who take a traditionalist not-how-things-are-done-here view of prices in the art market. “It is considered not ‘chic’ and is part of a wider ethos within the art market that monetary concerns are vulgar or impure and should not contaminate ‘pure’ artistic or aesthetic concerns,” Velthuis says.

The Art Basel viewing room as seen on a laptop. Photo courtesy Nate Freeman.

For the earliest patrons of the arts, price was no object. You could either afford to participate or you couldn’t, and the marketplace largely retains this Renaissance-era convention. But with the rise of the salon in the late 18th century, patrons began to disguise the financial aspects of the exchange. They saw themselves not merely as shoppers but instead “understood themselves to be joining a conversation,” says Nathan Clements-Gillespie, artistic director of Frieze Masters.

Dealers and collector-patrons colluded to claim that both sides were motivated purely by the priceless attributes of art, and not its role as a status marker, a symbol of wealth, an asset, and a form of capital.

“Historically, the art market has lacked transparency because the symbolic value of an artwork had to be highlighted as opposed to its existence as a commodity comparable to other non-symbolic goods,” says the art advisor Marta Gnyp. “And yet, despite the supposedly priceless quality of art, art functions not only as a socio-cultural market but also as a carrier of economic capital.”

The complex set of less-than-transparent mechanisms that determine art’s value also makes it easier to obscure its role as a commodity. For one thing, art isn’t produced on the scale of a global retailer with a uniform price structure. Another reason for the industry’s lack of price clarity is that it functions more like the stock market, says Hong Gyu Shin, who runs New York’s Shin Gallery.

“The lack of price availability of artworks is related to the various ways the value of art changes, which, like a stock, is reflected by the activities of various actors,” he says, and “the potential for art to either increase or decrease in value.”

But even still, the financial value of art is not only dependent on the price willing sellers and buyers agree upon, but also on art-historical references, provenance, and other areas of knowledge that are by nature not public. Instead, this insider knowledge is often exclusive to deep networks of families, business associates, and institutions.

Amani Lewis, Negroes in the Trees #3 (2019), which appeared in Christie’s “Say It Loud” sale. Image courtesy the artist and Destinee Ross-Sutton 2020.

When we claim that the art market lacks transparency, it would be more accurate to say that it lacks transparency for some people. “Value in the art market—as in most markets—is more transparent than it might first seem,” says Frieze’s Nathan Clements-Gillespie. “Value is clear to those who have done their homework and have researched the prices achieved in recent transactions, before committing to one themselves.”

While prices have not always been readily available, established collectors who understand how provenances work, know the patterns of pricing for a particular medium, or have relationships with galleries or advisors will have a better sense of what a work of art costs than a novice collector. Price availability, on the other hand, may be only helpful to a buyer without the knowledge and networks of a more experienced patron.

“For new collectors, visible pricing is a key educational facet of learning what is within their budget and builds confidence in their choices,” Soboleva says. “Collectors are excited when they discover David Zwirner has many works under $10,000, and that is wonderful to see.”

These new non-connoisseurs may include speculators who buy art purely as a financial asset, but also more welcome categories of collectors who had previously been shut out from the market simply due to their race or class.

Eniwaye, The Breakfast (2020). Image, courtesy the artist and Destinee Ross-Sutton 2020

The contract arranged by curator and art advisor Destinee Ross Sutton for the Christie’s selling exhibition “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” in August 2020 functions as a potential model for how to balance the upside of price transparency—to entice new collectors—while also guarding against speculation. The terms were that 100 percent of the sales would go to the artist, with a five-year hold on resale, at which point buyers who do choose to resell must give 15 percent of the profit back to the artist.

“I don’t want this to be a ‘thank you, come again’ situation—I want it to go beyond that,” Ross Sutton says. “There is a value in being a true steward of the work and potential patron of the artist and the arts, as someone who is trying to help move the culture forward in any way, as opposed to just buying and profiting from it.”

The worry among some that price transparency is eroding connoisseurship is not likely to go away anytime soon. And it remains to be seen whether new collectors and, in turn, the artists they support, really do benefit from greater price availability in the long term. Prices alone do not offer enough information to determine a good value when it comes to art. But since the online art marketplace appears here to stay, those once elusive price tags may be, too.

It looks like you're using an ad blocker, which may make our news articles disappear from your browser.

artnet News relies on advertising revenue, so please disable your ad blocker or whitelist our site.

To do so, simply click the Ad Block icon, usually located on the upper-right corner of your browser. Follow the prompts from there.