Tate Modern Finally Gives Pop Art’s Long-Ignored Female and Global Artists Their Due

Sep 17th, 2015 2:33 pm

Pop Art, the British artist Richard Hamilton famously wrote in a January 1957 letter, is “popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, big business.” Tate Modern’s show “The World Goes Pop,” opening to the public on Thursday, makes a case for adding “globalized” to that list.

For it is not the likes of Hamilton, Peter Blake, and Patrick Caulfield—British artists that occupy wall space in Tate Modern’s permanent collection—but 68 other artists from 29 countries mostly outside the U.S. and U.K. that are the subject of this exploration into Pop Art’s international idioms.

For it is not the likes of Hamilton, Peter Blake, and Patrick Caulfield—British artists that occupy wall space in Tate Modern’s permanent collection—but 68 other artists from 29 countries mostly outside the U.S. and U.K. that are the subject of this exploration into Pop Art’s international idioms.

- Bez Buntu (Without Rebellion), 1970

“This Pop Art is quite different,” says Tate Modern director Chris Dercon, speaking at the exhibition’s preview on Monday. “It’s the language of Pop telling another story: the story of politics, feminism.” According to the director, many of the artists on show were relatively unknown in their native countries, and this exhibition stands to reevaluate their significance.

The show is split into 10 rooms, with most of the art sourced from Pop’s apotheosis in the 1960s and ’70s. Recurring themes in the work—which varies dramatically in quality and taste—are the Vietnam War, the Cold War, civil rights issues, commerce, mass media, and protest. According to curator Jessica Morgan, director of Dia Art Foundation, these artists were often “unaware of what was happening in the U.S.,” and were addressing “a shift in the media and culture worldwide,” particularly the rising ubiquity of television and commercial art. In the work exhibited, they embraced the latter through subversion and replication as opposed to the vocabularies of their domestic avant-garde.

The Western counterpart to this is well known: in the U.S., Pop was a conceptual alternative to Abstract Expressionism, employing the language of advertising, cinema, and newspapers. It followed on from U.S. art critic Clement Greenberg’s definition of kitsch, accessible art borrowing from a fully realized cultural tradition, drawing “its life blood [...] from the reservoir of accumulated experience.” In “The World Goes Pop,” that pool contains depictions of everything from Hinduism and Chairman Mao to Leonardo da Vinci. Indeed, as one moves through the exhibition, the amount of competing cultural product is often overwhelming. The show’s curators have struggled to contain the quantity of work they have assembled, grouping rooms very loosely by theme—“Pop Politics,” “Pop Folk,” and “Pop Consumption”—leaving the viewer struggling to keep up.

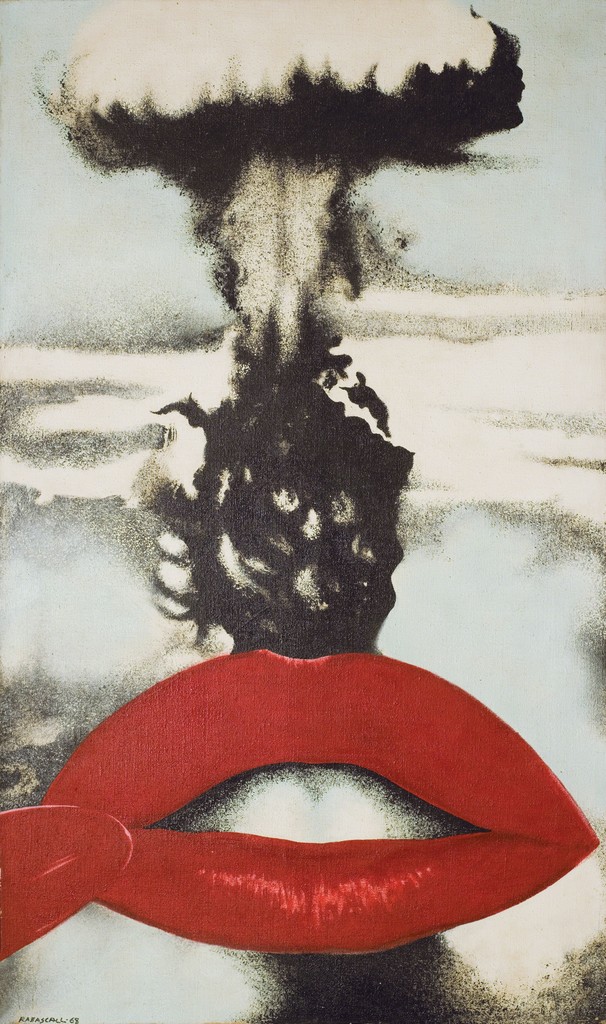

- Atomic Kiss, 1968

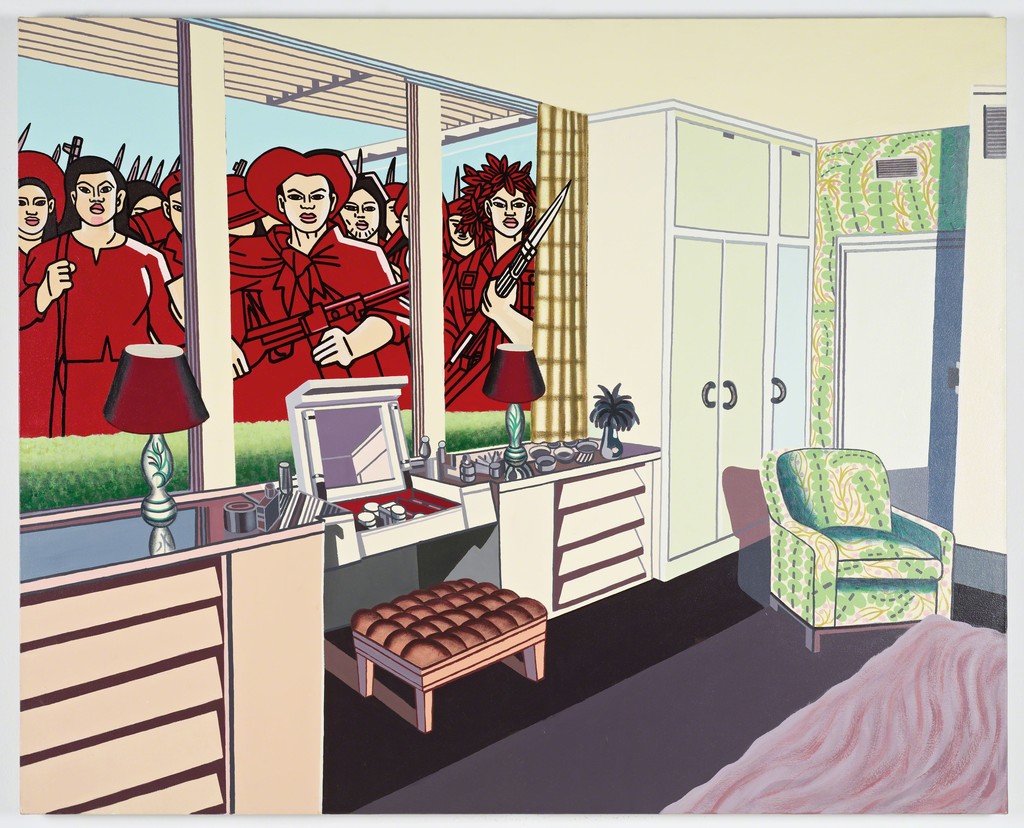

- American Interior #1, 1968

The first room serves as an introduction to the show, in which gimmickry and obviousness abounds. Jerzy Ryszard “Jurry” Zieliński’s Bez Buntu (Without Rebellion) (1970) shows a stylized face, its eyes eagles representing Polish national emblems, its fabric tongue extended out into three dimensions and nailed, silenced, to the floor. Nearby, Spanish collective Equipo Crónica has directly appropriated the language of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol in Socialist Realism and Pop Art in the Battlefield (1969), picturing El Greco issuing a speech bubble containing the entire canvas, a collage of Pop Art imagery inside. It is billed, rather evasively, as attempting to encapsulate “the global debate over representational art during the Cold War”—and feels as familiar as Peter Blake.

- El realism socialista y el Pop Art en el campo de batalla, 1969

- Bombs in Love, 1962

If Pop speaks to people in their own language, then its artists are most true to the movement’s ideals when appropriating the media. A room dedicated to Catalan Eulàlia Grau and Brit Joe Tilson is more effective in its messages. In Grau’s series “Ethnography” (1972-3), grainy prints of Richard Nixon, his eyes blocked out as if censored, are juxtaposed with an image of a chimp reclining in bed. Just opposite, Tilson’s work manages to avoid such triteness with his screenprint and wood relief, a fusion of pillow-like fabric sewn by Tilson’s wife, Joslyn Morton, and screenprints of Pop imagery—like the 1968 Olympics Black Power salute—along with articles laid out like the covers of revolutionary magazines.

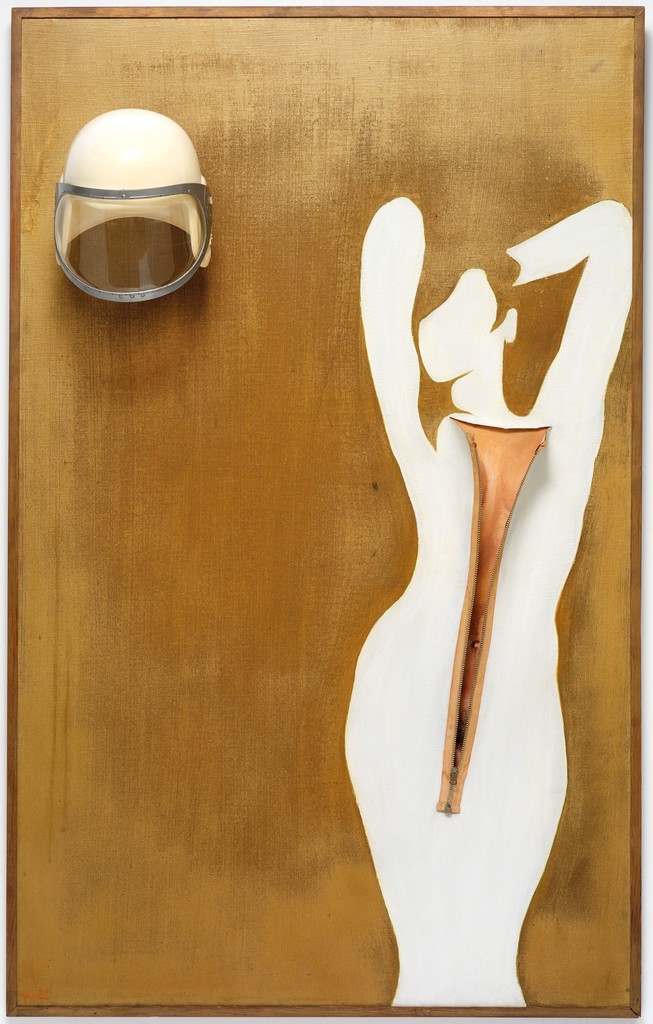

The show’s undoubted highlight is its strong women, showcased partly in a dedicated room exploring “Domestic Revolution.” These include the Argentine Marta Minujín’s Mattress (1962), a colorful, textile sculpture resembling a body (in their day users were allowed to interact with such pieces, re-enacting the artist’s experience of the object, but no such luck here) and Ruth Francken’s witty Man Chair (1971), based on a plaster cast of a male model, sexualizing anyone sitting on it. As curator Flavia Frigeri explains, “Very often Pop is associated with the male gaze, but when we started traveling we realized there were a whole wealth of women reflecting on their body. Not just [reflecting] on the way they were being depicted, but [reflecting] on their own selves.” Judy Chicago’s pristine “Hoods,” car hoods sprayed with sexual imagery, have a level of execution that puts much of the other art here in the shade.

Explore the Tate Modern on Artsy.

So is the show a success? For readdressing the U.S.- and U.K.-centric views of Pop Art, then undoubtedly it is. But due to the (over)abundance of material and its sheer density, some viewers may struggle to unite the nuanced concerns of the many competing nations here without greater cultural and political context.

—Rob Sharp

“The World Goes Pop” is on view at Tate Modern, London, Sept. 17 - Jan 24, 2016.

Explore the Tate Modern on Artsy.