|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Thursday, February 8, 2018

Pranks the Art World with Dumb Jokes—and Serious Painting Chops

Portrait of Jamian Juliano-Villani. Photo by Scott Indrisek.

The art world tends to play by its own inscribed rules and sense of decorum, but every now and then a foul-mouthed, chain-smoking, irreverent outlier from New Jersey comes around to upset that balance. Such is the case with Jamian Juliano-Villani, 31, a painter known for shoving compositional logic off a cliff. One typical example, from 2017, shows the artist as an orange tabby cat, lounging in the sunshine of a Greek island while surrounded by bottles of Proactiv skincare products. In The Pleasure Garden (2016), two ballerinas dip their toes into a garden salad while the portly shadow of Alfred Hitchcock looms above them. Everything is a blending of tones and moments, a borderland where sci-fi landscapes might tumble over borrowed Japanese advertisements, fonts cut from the New Yorker, D-list celebrities, classic animation, corporate logos, and one-liners.

A few years ago, Juliano-Villani was a studio assistant for the artist Erik Parker, laboring over her own paintings out of a cramped Brooklyn bedroom. She’s since risen to her own buzzy level of acclaim, with a fan club that includes the mega-curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist. The Whitney acquired a painting. She’s also had solo shows at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit, at Tanya Leighton in Berlin, and at Studio Voltaire in London. The artist now keeps a significantly more spacious studio in Ridgewood, Queens, where I meet her a few weeks after the opening of “Ten Pound Hand,” her most recent solo show at JTT in New York.

She’s a little hungover, and has just come from dealing with a domestic dilemma that seems ripe to be translated into a Juliano-Villaniesque painting: The artist has a mouse in her house. She’s nicknamed him Biscuit. She imagines him scrounging last night’s Indian takeout from the fridge, wrinkling his rodential nose in disgust.

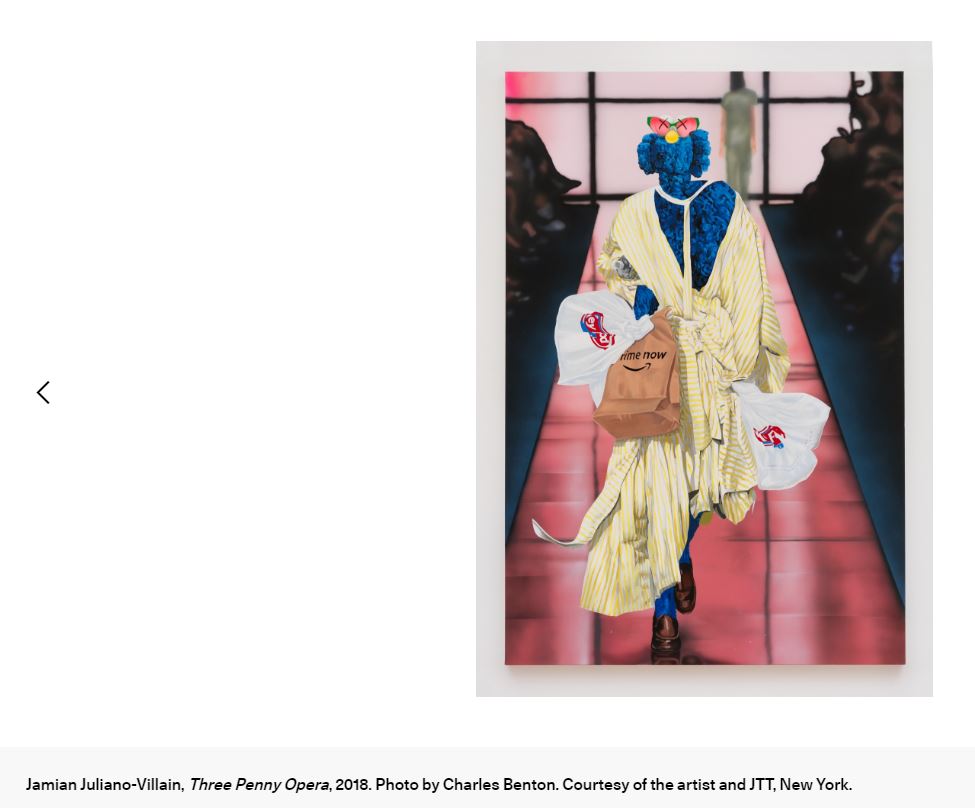

Jamian Juliano-Villain, October, 2018. Photo by Charles Benton. Courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York.

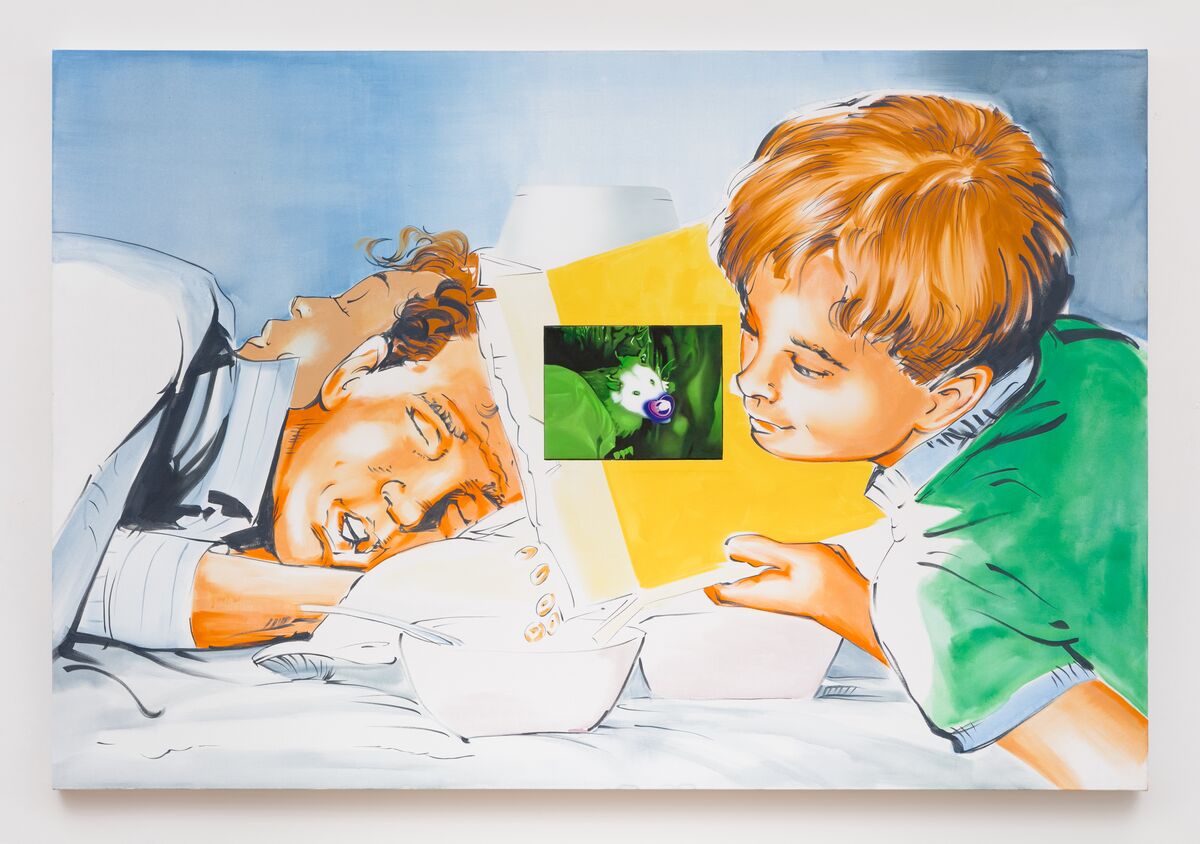

The studio at the moment is fairly bare, the blank walls streaked with the residue of paintings that have since shipped out. Small reproductions of the works in “Ten Pound Hand” are taped in one corner. “It looks like I had a seizure and made a show,” the artist says, reflecting on the selection, which includes a portrait of the white Texan rapper Paul Wall, a painting of a mob of motorbike riders on their way to a wedding, and a large-scale composition that appropriates a planning image for a cereal commercial and a hazy photograph of an opossum. That last one is called Penis Breath(2018), because, why not?

When asked if there’s a throughline connecting all of these disparate moments, Juliano-Villani tells me that she thinks of the works as a collection of self-portraits. They’re the product of intricate airbrushing, vinyl stencils, projectors, “drunk Photoshop,” and promiscuous appropriation. What they’re not—at least, in the artist’s mind—are an offshoot of Surrealism, or cartoons, two things that she’d really, really like critics to stop comparing her work to.

Juliano-Villani’s practice can seem both flippant (nothing matters!) and intense (everything is ridiculous and pointless, but it also still matters a lot, somehow!). “Ten Pound Hand” opens with a sort of confusing, purpose-built foyer room, in which the artist has hung intentionally crappy, graffiti-style works on the walls, and decorated the space with a rug branded with the logo for Robbi, a silk-screening company that her father runs. The blatantly ugly installation, which Juliano-Villani thinks of as a sort of send-up of bro culture, is called If Balls Could Talk (2018). The title “Ten Pound Hand” is a reference—to put this somewhat delicately—to a man’s overeager physical maneuvering in order to initiate oral sex.

Given all this lowbrow clowning, one could be forgiven for thinking that the artist is just messing around, having a laugh at the art world’s expense. In some ways, she is. But that middle-finger attitude is joined by a suspicious level of care and craftsmanship, not to mention a hypercharged work ethic. “I joke around about these being so dumb,” she says of her paintings’ subject matter, “but I love all of these things. I take them very seriously, and I’m not making fun.”

Yet at the same time, Juliano-Villani seems to be in tension with some basic existential issues—what painting can even do, for instance. When I ask her about Gone with the Wind (2018)—a photorealistic rendering of an image of the California wildfires, paired with a tiny, David Salle-style inset canvas depicting a fish drinking Coca-Cola—she seems to suggest that the goal is to have two images that “cancel each other out,” that end up at “nothing.”

During the course of our conversation she compares that sensation as akin to having two magnets pushed together, or to reiki; later, she draws an analogy between painting and the simple relief of defecating: “It’s embarrassing, but I’m glad I did it.” One painting-in-progress she equates to the aesthetic of R.L. Stine’s classic series of Goosebumps novels for young adults. “I don’t know what the point of these things is,” she says, other than, perhaps, “‘I haven’t seen something that stupid yet, and I wanted to make it.’”

5 Images

View Slideshow

The brainstorming process for Juliano-Villani’s recent work involved a lot of circuitous, labor-intensive research and development. Barely any of it ended up affecting the finished paintings, but the artist doesn’t seem to regret having wasted time. Through her friend Nathan Fielder of Nathan for Youfame—himself a sort of maestro of circuitous time-wasting—Juliano-Villani commissioned an L.A.-based comedy writer to generate dozens of short scenarios that she could then paint. The goal was to challenge notions of authorship, she says. “I thought it’d be interesting if someone else dictated what to paint, and I just did it,” the artist explains. “And if they sucked, I wasn’t responsible.”

Unfortunately, the ideas themselves proved unusable—too many specific brand references, for one thing. “A house made of Altoids tins belonging to Channing Tatum (we know this because the mailbox says ‘C. Tatum’ on it.) The house is nothing fancy, he’s a modest man!” read one. And another: “A person using a neti pot with spaghetti coming out of it OR a snake or SOMETHING other than snot and water, perhaps into a wine glass or into the mouth of a yelling person.”

Equally fruitless was an experiment in which Juliano-Villani and an artist friend visited a local bar, pretending to be affiliated with the ABC reality show Wife Swap, and asked strangers to fill out a Mad Libs-style form that could be used to generate future paintings. (Apparently everyone involved was drunk enough that this nonsensical cover story made sense.) “All these bros,” Juliano-Villani laments, recalling some typical answers, from equity to jell-o shot.

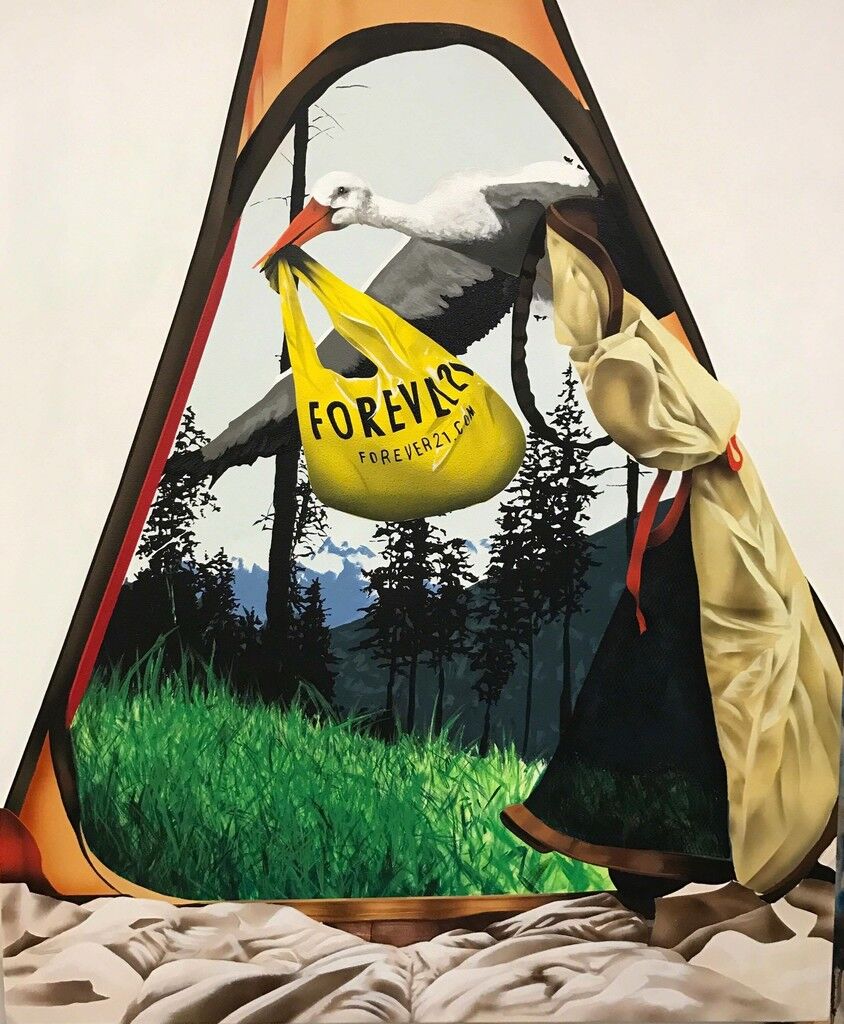

Jamian Juliano-Villain, Penis Breath, 2018. Photo by Charles Benton. Courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York.

Thankfully, the internet has always been there, waiting to be plundered. “I’m just the DJ, editing the playlist,” Juliano-Villani says of her basic tactic: scouring image databases, obscure websites, DeviantArt, and other sources for imagery that can be recontextualized. She’s not unaware that this can be a controversial move. Peers like Jeanette Hayes have been widely attacked for testing the line between appropriation and plagiarism; Juliano-Villani is no stranger to similar controversies.

Earlier in her career, the artist recalled, she might specifically request permission to sample someone’s work; for a painting that culled liberally from the animator Ralph Bakshi, Juliano-Villani made a personal call to get his blessing. “Now, if I did that for everything, I’d be on the phone all day,” she tells me. Plus, asking permission can drain some of the thrill. A 2017 painting in the JTT show borrows the face of a doll made by the artist KAWS. “I thought he was going to be pissed, [but] I asked him: Is this cool?” KAWS said it was, indeed, cool. “I was like: ‘Fuck! This is so not fun after he says it’s okay—it’s not evil anymore.’”

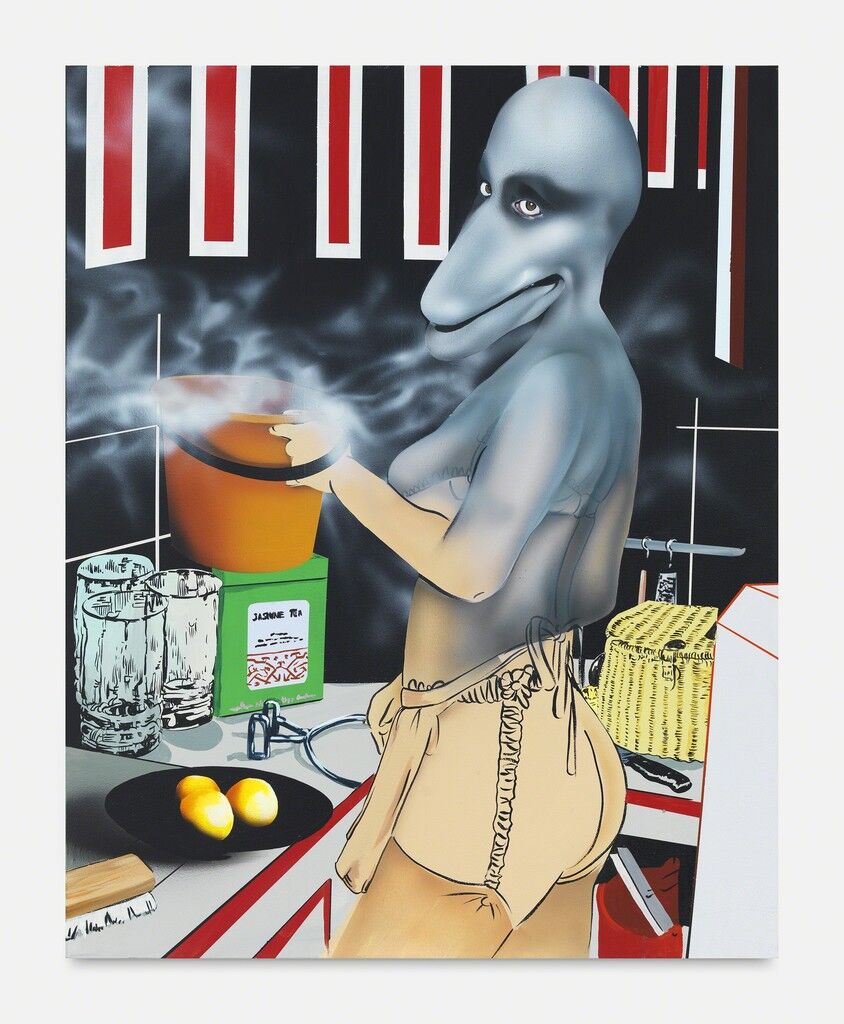

Jamian Juliano-Villain, Shut Up, the Painting, 2018. Photo by Charles Benton. Courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York.

For a 2016 work, My Memories Projected in the Hallways of the Titanic, the artist borrowed from herself. A vertiginous view of the interior of the doomed ship is populated by floating images—a BEWARE OF DOG sign, an external hard drive, a few ghostly heads—some of which are plucked from previous paintings. A brooch owned by Juliano-Villani’s grandmother is transformed into a Disneyesque figure, clambering up the Titanic’s staircase. Beneath all the pop cultural noise and absurdity, it’s a deeply sentimental picture.

And though she can sometimes seem eager to undermine the importance of painting, Juliano-Villani also feels a real responsibility to the medium—and to her strange, unlovely subjects. “It’s almost like no one wants to paint these things,” she says. “No one wants to paint Paul Wall, or a traffic light that says SHUT UP. A frog with a giant ass. But I want to. It feels like: Yes. Finally.”

Scott Indrisek is Artsy’s Deputy Editor.

Stay up to date with Artsy Editorial

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)