Older writers find younger ones irritating, Martin Amis writes in “The Rub of Time,” his fourth nonfiction miscellany, because their emergence is like a series of telegrams from the boneyard. “They are saying, ‘It’s not like that anymore. It’s like this.’”

Zadie Smith must be particularly galling to him. It’s not just that she was born in 1975, he in 1949. Her novels, beginning with “White Teeth” at the turn of the century, have deactivated many of the power instruments of Amis and his literary generation.

Smith, who is English-Jamaican, has prized open in her fiction a modern, multicultural, post-post-colonial England. In addition to being devastatingly good, her novels describe the ways society has changed in advance of phenomena like — to give just one example — the arrival of a figure like Meghan Markle as the Duchess of Sussex. Amis’s recent work can’t help but feel a step behind.

Yet they are friends, Amis and Smith. She warmly mentions him several times in “Feel Free,” her new book of essays. In his book, Amis says he reads her “with a constant smile of admiration.”

If this review were a text message, I would string kissy-face emoticons here. Instead I will simply cite the poet Paul Muldoon on the horror of “this tiresome trend / towards peace and calm.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In the way that all actors want to play Hamlet or Willy Loman, critics seem to have an innate desire to hurl themselves against Amis. Most want to knock the imaginary chip off his shoulder.

His scowling face — he seems to be sniffing his own sulfur — is, as the Twitter kids like to put it, strangely punchable. Critics like to write about Smith because it allows them to sagaciously read the tea leaves of fiction and society.

I’m here to do neither of these things; not primarily, at any rate. Amis’s new book, like the collections that preceded it, is the product of a ferocious yet sensitive mind. Even when he is considering writers he’s assessed many times before (Saul Bellow, Philip Larkin, John Updike, Christopher Hitchens), his aim is so unerring that he resembles a figure out of Greek myth, firing arrows through ax-heads lined up in a row.

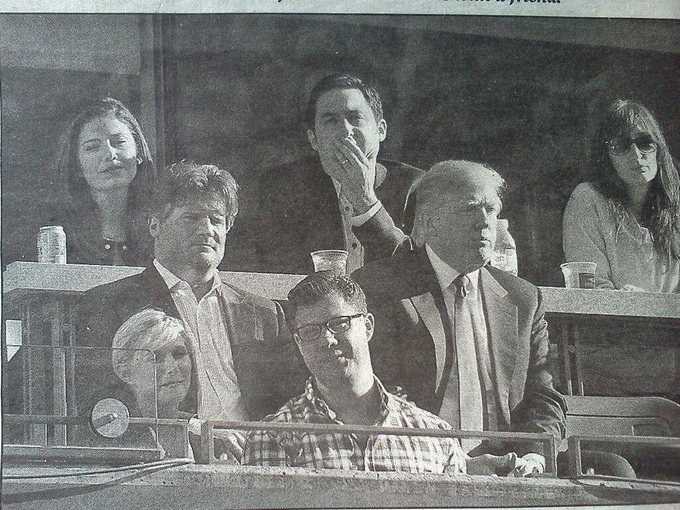

He also visits a porn set in Los Angeles (disgusted, he leaves before the money shot), plays in the World Series of Poker, and considers book tours, tennis, terrorism, Princess Diana and the era of Donald J. Trump, about whom he writes: “There’s nothing there. No shame, no honor, no conscience, no knowledge, no curiosity, no decorum, no imagination, no wit, no grip and no nous.”

Smith’s “Feel Free” is a gentler ride. If Amis’s book is like hurtling down a black-diamond ski run, hers is more like a brisk day on the cross-country trails. She writes a good deal about art and gardens and travel, and about non-controversial — at least for her New York Review of Books readers — topics like libraries (good) and global warming (bad).

In the best of these pieces, however, Smith presses down hard as a cultural critic, and the rewards are outsize. Who else would deliver an observation quite like this one, from her profile of Jay-Z?:

“Asking why rappers always talk about their stuff is like asking why Milton is forever listing the attributes of heavenly armies. Because boasting is a formal condition of the epic form.”

Smith prints two shrewd pieces about Jordan Peele, one before and one after his success as the director of the indie horror movie “Get Out.” Here she is on the compendium of black fears that Peele’s movie illuminates:

“Banjos. Crazy younger brothers. Crazy younger brothers who play banjos.” And: “Well-meaning conversations about basketball. Spontaneous arm-wrestling, spontaneous touching of one’s biceps or hair. Lifestyle cults, actual cults. Houses with no other houses anywhere near them. Fondness for woods. The game Bingo!”

Trump figures only slightly in Smith’s essays, which were written almost entirely before his presidency. But in a bitter piece about Brexit composed for The New York Review of Books, she takes aim at its spiritual fathers, David Cameron and Boris Johnson.

About them, she declares: “‘Conservative’ is not the right term for either of them anymore: that word has at least an implication of care and the preservation of legacy. ‘Arsonist’ feels like the more accurate term.”

For six months, Smith was a book critic for Harper’s Magazine, and the results are printed here. These reviews are a mixed bag, mostly because the titles seem random and often infra dig.

She’s penetrative, however, on the Mitfords and Edward St. Aubyn and Paula Fox and the essayist Geoff Dyer, about whom she notes, perfectly, “Dyer seems always to be questing to comprehend somebody else’s quest.”

The topic of aging surfaces frequently in Smith’s essays. She’s 42, no longer the whiz kid, and she’s considering how to be in middle age. Aging is the upfront obsession, from the title onward, of Amis’s essays.

“Writers die twice,” he observes in an essay on Nabokov. “Once when the body dies, and once when the talent dies.” Can we pinpoint when a writer’s talent begins to fail?

Amis posits that Nabokov’s prose started to lose velocity with the novel “Ada.” The last good novel from his father, Kingsley Amis, he suggests, was “The Old Devils,” though he went on to write five more.

Updike’s final collection of stories, “My Father’s Tears,” Amis reviews posthumously and finds to be “perhaps his least distinguished,” the stories “products of nothing more than professional habit.”

It’s an assessment Amis hates to commit to print. He wouldn’t have done so, he writes, were Updike, whom he elsewhere called “a NORAD of data gathering and microinspection,” still alive.

How many strong books does Amis, who will be 70 next year, have left in him? “We are all of us held together by words,” he writes here. “And when words go, nothing much remains.”