Your complimentary articles

You’ve read all of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Further History of Sexuality: From Michel Foucault to Miley Cyrus

Peter Benson philosophically explores changing attitudes towards sexuality.

When Michel Foucault died in 1984 he left unfinished a proposed sequence of four books with the overall title The History of Sexuality. Only the first three volumes were published. Furthermore, his plan for the sequence had changed drastically between the publication of the first volume in 1976 and the second, which appeared in the year of his death. One thing he didn’t change, however, was the title of his project, and this was quite enough by itself to ruffle the feathers of his many detractors. Although attitudes to sexuality clearly change over time, can it be right to claim that human sexuality itself has a history? Surely it is a natural characteristic which only alters in the long, glacially slow perspective of evolution?

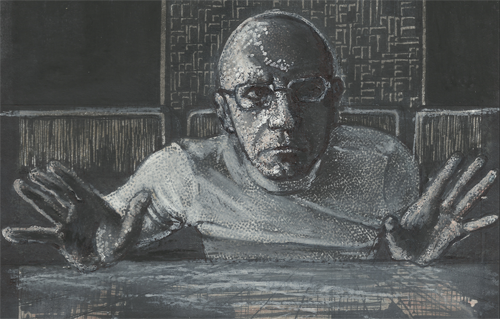

French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926-1984) portrait by Woodrow Cowher, 2017

A History of Foucault’s Thought

Questions of this kind were not new issues in relation to Foucault’s work. They had been a source of controversy ever since the time of his first major book, The History of Madness (1961). There, too, the title promised not merely a history of the treatment of madness, but a history of madness itself. This implies that madness too belongs among the category of things that have a history, not among those that are historically unchanging facets of human existence. Foucault disputed that there was a readily recognizable human ailment called ‘madness’ which had always existed, but had been treated differently in different eras. Rather, the way we talk about madness – the particular behaviours that we characterize by this term – changes over time, and there is no way to recognize who is mad outside of this shifting discourse. This gives to madness a narratable history.

It is at this point that a number of misunderstandings are apt to arise, which are used to berate Foucault as well as similar thinkers in the Continental tradition, so it is important to emphasize what he is not saying. He is not claiming that there is no reality to madness outside of our discourses about it. No-one, to the best of my knowledge, has ever seriously made such a claim. Experiences of madness are undoubtedly real, serious, and distressing. Their causes may lie either in neurological or social conditions, or perhaps some combination of both. As yet, however (despite the frequently excessive confidence of psychiatrists), we are unable to catalogue these causes with any confidence. In the meantime the category of ‘madness’ variously morphs according to changes in our theories. These shifts, widening or narrowing the class of ‘the mad’, can be mapped chronologically. By becoming aware that madness was once thought of in very different terms from our own, we can acquire a degree of detachment from current views, rather than being immersed blindly within them. In this idea, as in many other ways, Foucault was greatly influenced by Nietzsche, who wrote of the importance of ‘untimely’ thoughts – thoughts at odds with those of our present era, either because they are borrowed from the past, or because they presage a different future.

Similar ideas sustain Foucault’s History of Sexuality. Here too he wanted to challenge the view that human sexuality was a fixed feature of our biological and psychological lives which different societies have variously sought to limit, condemn, or express. On the contrary, Foucault takes the view that the diverse forms of human sexuality are brought into being by the way they are discussed: the biological basis of sexuality is elaborated and shaped by the language we use to describe it. Indeed, the very concept of someone having a ‘sexuality’ is a very recent idea, which did not exist before the eighteenth century.

Today we are familiar with discussions about people’s sexuality, which is usually taken to refer to whether they are homo-, hetero-, or bi-sexual. But Foucault explains in the first volume of his History that although for many centuries in Europe the law forbade and punished homosexual acts, it was only in the nineteenth century that individual people began to be spoken of as ‘homosexuals’. Foucault dates the idea of ‘the homosexual’ as a particular type of person, with distinctive psychological characteristics – rather than someone who succumbs to a vice that might be a temptation for anyone – to an article published in 1870. As he writes: “The sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species” (p.43). However, this characterization “also made possible the formation of a ‘reverse’ discourse: homosexuality began to speak in its own behalf, to demand that its legitimacy or ‘naturality’ be acknowledged, often in the same vocabulary, using the same categories by which it was medically disqualified” (p.101).

This exemplifies Foucault’s general theory that all social and political power generates its own opposition, creating conflict even as it tries to suppress it. Thus the term ‘homosexual’, designating a particular class of persons, was first used by figures in authority: doctors, psychiatrists, judges. It named a particular problematic group who might then be subjected to treatment, punishment, or tolerance. Even those who advocated a relaxed attitude towards these people did so, first, by characterizing them and then, most typically, declaring the causes of their condition to be irreversible. In a second stage of this historical process, the designated group adopted and adapted their designation, accepting the term ‘homosexual’ or some equivalent, and regarding themselves as representatives of a suppressed and misunderstood group, engaged in resisting social oppression. Hence began a long process of covert and overt protest, from the time of Oscar Wilde to the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1970s. The self-adoption of the word ‘gay’ as a non-pejorative alternative to other slang terms, and the promotion of this word until it has now become generally accepted, was an immensely successful example of linguistic rebellion, running in parallel with, and influencing, the steady change in social attitudes. The central Foucauldian point, however, is that it was power which created the category ‘homosexual’, which then became a location of resistance to that power. That is to say, power creates its own resistance: the resistance does not come from somewhere outside the particular regime which provokes it.

Once this resistance had led to the crumbling away of condemnation and punishment, however, there was no longer any strong need for people designated ‘homosexual’ to band together in solidarity against their oppressors. Nor was there any need to think differently about homosexual activity than any other variety of sexual interaction. In the years since Foucault’s death, these taboos have indeed largely evaporated. Many people no longer feel that homosexual actions would put them into a special social category, and hence they no longer have any strong motivation to avoid them. This new situation has been accurately described by the actress Kristen Stewart, who, in response to a question about her sexuality, said, “I think in three or four years there are going to be a whole lot more people who don’t think it’s necessary to figure out if you’re gay or straight” (Nylon magazine, 2015). The only word Stewart is willing to use about herself in this connection is ‘fluid’. This is a word that has recently become fashionable, and has also been used by, among others, the model and actress Cara Delevingne and the pop star Miley Cyrus, who has become a vocal spokesperson for these new attitudes. She has not only given voice to the experiences of many people today, but also influenced attitudes among her wide audience.

In an interview with Le Monde newspaper in 1980 Foucault had declared:

“From philosophy comes the movement through which… one detaches oneself from received truths and seeks other rules of the game… [it brings about] the modification of received values and all the work [is] done to think otherwise, to do something else, to become other than what one is.”

He therefore concluded that we should recognize philosophy as wherever analysis is accompanied by “changes in behaviour, the actual conduct of people, their relationships with themselves and with others.” It follows that philosophy is not something to be left to professional philosophers. Original ideas can bubble up in many different areas of our culture, and, when they are challenging received opinions, may equally deserve the name of ‘philosophy’. Clear thinking and fresh thoughts are far from being the preserve of academics. (Indeed, academia is often the last place one should look for them.)

Miley Cyrus: Pansexuality

Throughout 2015 Miley Cyrus gave a series of interviews which in my view place her at the forefront of contemporary thinking about gender and sexuality. Provocative and clearly expressed, these interviews ably display her considerable intelligence and honesty.

But before discussing what she had to say, I’d first like to take a step back, to explain what had led her to take such a public stand on these issues and to become (in the words of one of the magazines that interviewed her) “the world’s most unlikely social activist.”

Miley Cyrus, a popular singer

Photo: facebook.com/mileycyrus

Miley has been a popular and successful singer since the age of fourteen, when the Disney TV channel gave her the lead role in their children’s programme Hannah Montana. Her attitude towards her financial success, however, is remarkably refreshing and unusual in our highly competitive society. “People in this industry think ‘I just gotta keep getting more money’, and I’m like, ‘What are you getting more money for? You probably couldn’t even spend it all in this lifetime’… The question is: what am I going to do with it? I don’t want to just sit and hoard it. Or chase more.” She adds that “I should not be worth the amount I am while people live on the streets. Nothing I do will justify that. But I have so much influence as a pop star, it’s important I use it” (Marie Claire, US, Sept 2015).

Miley was particularly concerned about the number of homeless young people she could see on the streets of L.A., and began to investigate the reasons for it. It quickly became evident that one of the most common reasons for a teenager to be living on the streets was that their parents had thrown them out for being gay or otherwise sexually unconventional. This shocking fact made the issue very personal to Miley, whose own sexual feelings had never been confined to a single gender. In different circumstances, with less supportive parents, she herself might have been sleeping under a bridge somewhere.

Determined to take some action on this issue, her campaign has taken three routes. First, she set up a charity (the Happy Hippy Foundation) to offer practical help to homeless young LGBTQ people. Secondly, she made various public pleas for tolerance, emphasizing that she was not trying to change anybody’s way of life, only asking them to be more accepting of different lifestyles. Thirdly, she has spoken candidly about her own life and feelings in the interviews I mentioned. It is not unusual today for people in the entertainment industry to announce that they’re gay or bisexual – in such circles at least, prejudice has largely evaporated. Miley, however, dislikes the word ‘bisexual’, and prefers ‘pansexual’ to describe herself. For one thing, ‘bisexual’ implies that there are just two sexes to choose from, into which everyone falls. This is factually untrue. Hermaphroditism, or intersexuality, is far more common than most people realize. By some estimates, one in every two thousand babies has intersex characteristics, which, world-wide, is several million people. So even physically, not everyone is clearly male or female. If one adds to this the social and psychological assumptions that have accrued around ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’, a great many more people will not be readily classifiable in those terms, or will feel uncomfortable with any such classification.

“I don’t relate to being a boy or a girl,” explained Miley, “and I don’t have to have my [sexual] partner relate to [being] boy or girl.” She contends that “Once you’re an adult, you can choose who you are. We’re born humans… I don’t relate to what people have made men and women into” (Elle, UK Oct 2015). When she finds somebody attractive, she explains, she is responding to that person as an individual, not as a member of a category such as ‘male’ or ‘female’. What type of genitals they have is not important until one is actually making love, at which time one can modulate one’s behaviour accordingly.

Many people may find this attitude difficult to empathize with. But a practical demonstration can be found in Miley’s ‘InstaPride’ campaign, which invited transsexuals and others of indeterminate or unfixed gender to post pictures of themselves on Instagram. Some of these people are very obviously physically beautiful, without us knowing anything about their genitalia. So it becomes clear that we can find someone attractive without knowing their gender. Attraction to a particular person comes first, and knowledge of their gender is secondary. In the face of this refreshing attitude, the work of academic feminist philosopher Judith Butler begins to seem timid: her theories never leave behind the binary divisions of conventional gender, or the alternatives of being either homo- or heterosexual. People like Miley have moved on from such limiting perspectives.

At the end of her concert performances in 2015 Miley took to the stage wearing a colourful wig, a horse’s tail, fake breasts, a unicorn’s horn in the centre of her forehead and a huge sculptured phallus strapped to her crotch. In this wonderful costume she drifted gently round the stage singing her poignant song, ‘Karen Don’t be Sad’. In this context the song became a supportive call to all gender non-conformists to resist attempts at normalization: “’Cause they’ll crush you if they can/They’re just a bunch of fools/And you can make them powerless/Don’t let them make the rules.”

In June 2015, Miley posted a picture of herself on Instagram (where she has 26 million followers) wearing a T-shirt bearing the slogan ‘Gender is Over’, and looking very cheerful about the idea. She has remarked that in the past, when people asked her for an autograph, they used to mention some song or performance of hers that they particularly liked, but now the most common thing they say is, “Thank you for what you stand up for.”

It will certainly take some time for her views to become widespread, but there is a definite movement underway, which could not have found a better spokesperson. There is nothing hectoring or aggressive in her pronouncements, but only good humour and tolerance. It is worth remembering that she first became popular on childrens’ TV because of her likeable personality, and that is one thing that hasn’t changed at all.

Shulamith Firestone & The End of Gender

The end of gender was predicted in 1970 by the feminist philosopher Shulamith Firestone in her book The Dialectic of Sex. There she wrote:

“The end goal of feminist revolution must be…. not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally. (A reversion to an unobstructed pansexuality … would probably supersede hetero/homo/bi-sexuality)” (p.19, her emphases).

At the time this probably seemed like a utopian dream, but as we have seen, it is now coming much closer to realization.

Firestone’s brilliant book is the Das Kapital of feminism. Building on the work of Marx and Engels concerning the primary division of labour between the sexes in prehistory, Firestone argues that no socialist revolution will be complete until this original division is overcome. In the same way that Marx saw the industrial development of society as the basis on which class division could be overcome, no longer serving any necessary purpose, so Firestone saw the development of greater control over reproduction through contraception and other medical technologies as the necessary ground for ending the class division between men and women. Industrial technology also has its part to play, as it ends any need for brute strength as an advantage in human activities. Hence all forms of employment become open to both sexes, and discrimination by gender-class is unnecessary. Indeed, in many countries it is already illegal. In this context, Firestone predicted, the social significance of gender will begin to evaporate.

Firestone shares Marx’s belief in the dialectical nature of historical transformations, whereby history progresses through the clash of opposing classes or ideas. This is one point that distinguishes her from Foucault, who avoided making predictions about the future course of social change, and always remained wary of the dialectical philosophies of history propounded by Hegel and Marx. However, this dichotomy between Foucault and dialectical philosophy is not as absolute as it might appear. In his 1970 inaugural lecture at the Collège de France, Foucault suggested, “we have to determine the extent to which our anti-Hegelianism is possibly one of his tricks directed against us, at the end of which he stands, motionless, waiting for us.”

The widespread anti-Hegelianism in French philosophy at the time was in part the result of contentious interpretations of Hegel – notably those of Alexander Kojève – which placed an undue emphasis on historical inevitability and on the all-embracing completeness and closure supposedly possessed by Hegel’s system. It is in Kojève’s writings, not in those of Hegel himself, that we find the notion of an eventual ‘end of history’, later popularized by Francis Fukuyama.

Until recent years, the considerable popularity of Kojève’s interpretations of Hegel prevented more subtle engagement between political philosophy and Hegelian thought. Today, writers such as Slavoj Zizek have helped to free Hegel from these misleading interpretations, and it is now easier to see how much Foucault and Hegel have in common. For both thinkers, historical change takes place not as a continuous evolution but through abrupt transformations, in which one form of society is replaced by another. For Foucault, the difference between these regimes was correlated with different arrangements of political and social power. Hence in Discipline and Punish (1975) he contrasts the unified sovereign power of the feudal era with the more dispersed and fragmented disciplinary power of industrial society. But he does not directly address the causes of these changes. By contrast, Firestone considers that “feminism is the inevitable female response to the development of a technology capable of freeing women from the tyranny of their sexual-reproductive roles” (p.37). Furthermore, “Culture develops not only out of the underlying economic dialectic, but also out of the deeper sex dialectic” (p.179).

As we have seen, Foucault’s analysis of the shifting significance of homosexuality in Western culture over the last two centuries identifies two stages, corresponding to the production by power of its own opposition:

(i) Homosexuals identified as a ‘deviant’ group, the target of medical and legal intervention.

(ii) Homosexuals accepting this identity, as gay people, and campaigning for equality and integration into general society.

This second stage can be said to have culminated in the recent acceptance, in many countries, of gay marriage. But the ending of thisconflict inevitably generates a completely new situation, in which:

(iii) The division homosexual/normal having been overcome, the category of ‘homosexual’ itself loses its rigid borders and begins to dissolve into contemporary ‘pansexuality’.

With this third step, which has only developed in very recent years, since Foucault’s death, we can see a new dialectical triad beginning to form. This is the kind of triad which, for Hegel, Marx, and Firestone constitutes the underlying structure of historical development. So, although Firestone predicted pansexuality to be one of the results of a feminist revolution, we can today see it as contributing towards that revolution, bringing it closer to realization. Such a revolutionary change, bringing about an end to the oppressive social structures of gender, will soon produce a better world for everyone: women, men, and everyone else as well. It is time for all of us to embrace and encourage these changes.

© Peter Benson 2017

Peter Benson accepts the pronoun ‘he’, but considers himself to be gender neutral. His favourite Miley Cyrus track is ‘Space Boots’.