Art dealers have the experience economy all wrong

And it's hurting their chances with the young clients they need

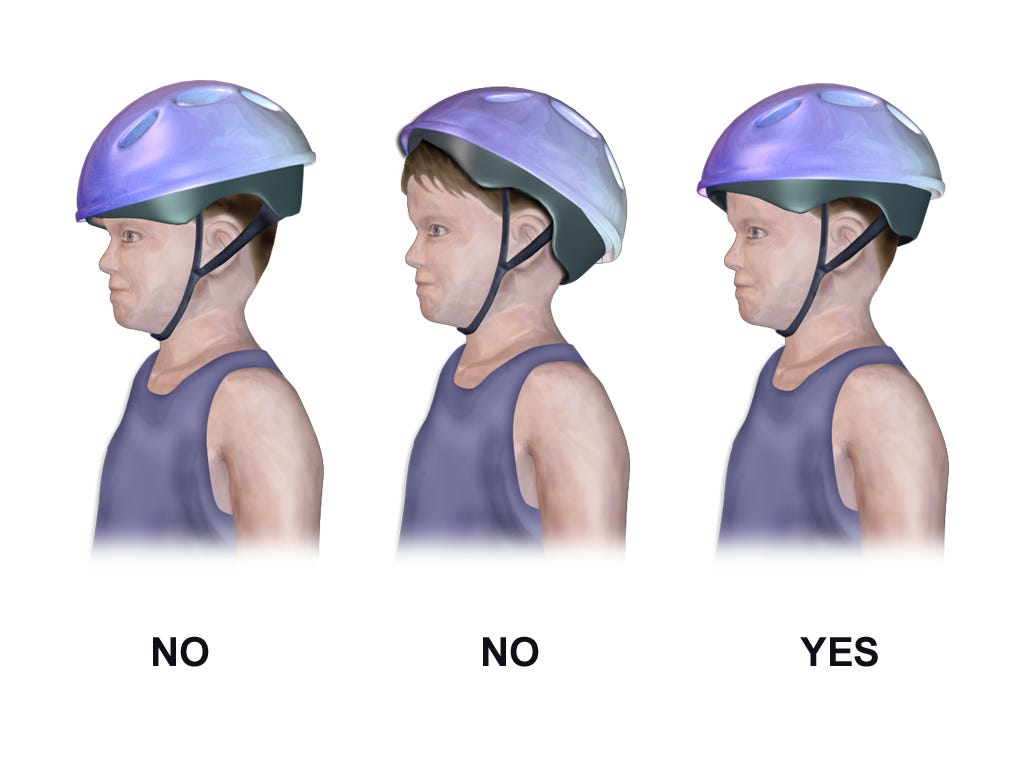

A 2016 instructional graphic on the proper placement of a youth bike helmet. Image by Bruce Blau, courtesy of Wikimedia (via Creative Commons license)

I’ve joked before that the art industry has gotten so obsessed with the marketing potential of “immersive experiences” that some galleries have used the phrase to describe shows with paintings hung on all four of their walls. But the deeper I’ve dug into the challenges of getting younger people interested in buying art, the more convinced I’ve become that there’s some counterintuitive wisdom buried in what I used to think was just a decent punchline.

Within the art trade, the most prominent narrative about people under age 45 is that they tend to be more interested in spending money on experiences than objects—a storyline that seems to have begun around 2018 with a study paid for by, it’s often forgotten, a live-events company.1 This preference allegedly makes millennials and zoomers tough to convert into collectors and even tougher to envision evolving into connoisseurs. The framework has a foundation of truth, but I’m concerned that it’s also been exaggerated into a false binary that’s now hurting art sellers’ prospects for connecting with younger clients more than it’s helping.

The reason is simple: positive experiences have a long track record of motivating people of all ages to buy related stuff, even when the experiences themselves cost a sizable amount of money in the first place. An entire universe of souvenirs, memorabilia, and merchandise depends on this dynamic, in fact, and selling it has been a good business for a very long time.

Live music is one case in point. While global ticket sales for concerts generated an estimated $34.8bn in 2024, per the analytics firm Custom Market Insights, people spent another $14.0bn worldwide on physical and digital music merch, according to the industry research group Midia.2 Granted, not all of that buying happens at live shows, but enough of it does that the merch booth has been the touring musician’s sturdiest lifeline in the post-Covid streaming economy.

One of my core principles is that the art business has to be understood first and foremost as a social network. The number of people who buy paintings, sculptures, drawings, and other physical works exclusively from a cold, clinical distance may not be zero, but it’s pretty damn close. This is why dozens and dozens of Silicon Valley Geniuses© have failed to revolutionize the art market by focusing on making the process of buying work as frictionless as possible: a lot of the so-called “friction” is what makes collectors care enough to spend the money!

Take away the opening receptions, the studio visits, the art fair weeks (including all the related parties and activations), the Saturdays spent gallery hopping, the panel discussions, the conversations with other art people about which artists you’re thrilled by and which ones you’re sick of (or even which ones are a good investment and which ones’ markets are tanking), and what do you have left? The bloodless efficiencies of pure-play e-commerce, which reduces even good artworks to terminally unsexy home décor items.

If you were looking for one word to encapsulate all the aforementioned events, relationships, and other participatory encounters that elevate art into a passion for thousands of people, you could do a lot worse than calling them a grand “immersive experience.” In that sense, a gallery show with paintings on all four walls really could qualify as one, too, as long as it’s thought of as a single component of this larger, intangible whole.

Once the art industry is understood in this way, doesn’t it start to sound, frankly, kind of dumb to believe that young people’s interest in memorable experiences would be an obstacle to selling them objects that double as permanent points of connection with those experiences?

If you disagree, it effectively means arguing that Broadway fanatics are generally against buying memorabilia from productions they love, that amusement park maniacs are mostly immune to spending extra cash on souvenirs of their favorite rides, or that people who love scuba diving would have no interest in installing home aquariums to house cool tropical fish. All of which sound dubious to me. So why should the decision tree work any differently with art?

Talking back

The automatic rebuttal to my line of logic here is that merch from a music festival or a stage play, let alone a novelty keychain of the Eiffel Tower sold by some random Paris street vendor, costs so much less than a work of art that it’s stupid to compare them. But this counterargument is flimsier than it seems at first glance, in two respects.

First, the width of the financial gap between the categories in question depends a lot on how you define the terms. If you’re comparing, on one hand, some 19-year-old hessian plunking down $30 for a t-shirt of their favorite metal band after moshing their brain out at a free show in some disused warehouse and, on the other hand, some young private equity bro buying a $300,000 painting from the VIP opening of a serious art fair during a trip to a glamorous international city, then I’ll admit that it’s awfully tempting to just dismiss the entire equivalency exercise.

But what about if we instead consider someone who paid $5,000+ for a special “Club Renaissance” floor seat at Beyoncé’s 2023 tour and another $600 for a Balmain-designed hoodie from the merch booth? Is it fair to use that person, who spent around $5,600 combined, as a comp for, say, a young lawyer interested in buying a $5,500 painting by an emerging artist they fell in love with after getting into NADA’s most recent New York fair with a $55 single-day ticket? Personally, I think it is.

This leveling of the playing field leads to my second counter: the dollar value someone spent on an object is only as meaningful as your knowledge of how much of a discretionary bankroll they had to work with in the first place. Imagine our hypothetical teen metal fan above is supporting himself on a part-time, minimum-wage job that only makes ends meet if he goes to depressing extremes on food and shelter. Suddenly, spending $30 on a band t-shirt looks more like a serious financial commitment than a throwaway purchase, doesn’t it?

The same could be said for working-class parents who scrimped and saved for months to take their three kids on a day trip to Disney World, then spent another few hundred bucks on stuffed animals, novelty popcorn buckets, and commemorative rollercoaster photos while they were there. One person’s souvenir is another person’s meaningful splurge. It all depends on your resources.

When art pros talk about potential next-generation collectors, it’s understood that the people in question are wealthy, or at least wealthy enough to buy art without thinking all that much about the financial impact. So when comparing art spending to other types of purchases spurred by other types of experiences (paid or not), it’s the consumer psychology that matters most. And on that front, much of the art business is still missing the key lesson.

Updating the experience economy

For art sellers angling for young clients, the operative question isn’t so much “How do I sell art objects to people who are mainly interested in paying for memorable, positive experiences?” It’s more like “How do I make buying art objects feel like part of a memorable, positive experience?”

On one level, this isn’t such a different question than what some dealers have been asking themselves for decades. Some of the most successful galleries since at least the middle of the 20th century have built their business on creating a lively, exciting scene around their program. In those cases, collectors who bought from them weren’t just acquiring objects; they were supporting the entire social and cultural ecosystems that influenced the production of those objects. In other words, they were effectively buying souvenirs of immersive experiences that could go on for years.

Campaigns like this are taking on new forms at the top of the gallery sector. The most extravagant example is the growing empire of upscale hotels, restaurants, and bars owned and operated by Manuela and Iwan Wirth, two of the co-founders of mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth.3 But dealers aren’t the only entities in the art business pushing the traditional boundaries of scene-building in the 2020s.

Art fairs, for instance, understand that cultivating welcoming, enriching experiences for visitors makes those visitors more likely to buy art from their exhibitors (who are the fairs’ main clients). But hospitality may need to look different if the goal is to embrace genuinely new demographics. For instance, at its Miami Beach show in 2024, Art Basel partnered with Airbnb to offer three types of paid experiences, including one in which the fair’s director, Bridget Finn, led ticket-buyers on a tour through the aisles. An initiative like this probably would have been heretical to Art Basel’s founders in Switzerland 50+ years ago, but try running a 1970s playbook on just about any aspect of our current era and let me know if it lands you anywhere other than in a quagmire.

None of this is to say that dealers need to become corporate partners, let alone hoteliers or restauranteurs, to sell art to people under age 45. On the contrary, I think newer galleries run by newer blood actually have an advantage, especially in this unsettled economy, because they’re free of the monolithic stature and elitist expectations of their counterparts at the high end. What could be better for building an ongoing “immersive experience”—which is to say, a scene—than the license to be nimble, experimental, and unabashedly excited about what you’re showing and how you’re showing it, especially if you’re making everyone who comes by to see it feel like they deserve to be there regardless of their background?

The recipe isn’t easy to execute by any means. But we’ll learn a lot more about art’s appeal to young buyers from those few intermediaries who can pull it off than we will from years-old talking points sponsored by an events company.

Again, in the immortal words of the late investor Charlie Munger, show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome.

I considered using ticket sales for live sporting events and spending on sports merch as another reference point, but the data there reinforces my suspicions that direct experiences aren’t necessarily what’s driving sales of jerseys/kits, team/club t-shirts, and more. Custom Market Insights found that ticket sales for live sporting events in 2024 reached $20.5bn, which is actually around 44% less than the estimated $36.4bn spent on licensed sports merch in the same year, according to Grand View Research. That imbalance makes sense since so much sports fandom revolves around TV and radio broadcasts, but it also makes this too messy a comparison to be of much use in a post about art’s experience economy.

Technically speaking, the various properties I’m referencing here—like the two Manuela restaurants in New York and LA, the Fife Arms Hotel in Scotland, and London’s members-only Groucho Club—are owned by Artfarm, an entirely separate company established by the Wirths. At the same time, the hospitality properties are so infused with work by Hauser & Wirth’s artists that it seems willfully blockheaded to view the two firms as anything other than symbiotic.