United Nations Headquarters - North by Northwest, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959)

From Vertigo to Psycho, how Hitchcock changed the role of architecture in film

Writer: Pete Collard

This summer sees a limited cinema re-release of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, timed to celebrate the film’s 60th Anniversary. Although originally released to a lukewarm reception, the film has today become one of the most acclaimed cinematic works of the 20th century and marks an important moment in the director’s pioneering approach to architecture and interiors.

Podesta Baldocchi florists - Vertigo, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Paramount, 1958)

Ernie’s Restaurant/Shipyard offices - Vertigo, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Paramount, 1958)

As a director Alfred Hitchcock was responsible for some of the most seminal moments in cinematic history. His career in film began as a production manager and set-designer, formative experiences that would later help to develop his unique visual style when in charge of the camera. For each of his films he would sketch pages of storyboards and layouts, often based on real locations, that his design teams would then build. For Hitchcock, a film set was never simply a background for the actors, each acts as a supporting character within the plot and is used to channel the psychological mood of the scene.

Based on the 1954 novel D’Entre les Morts, Vertigo follows ex-detective Scottie Ferguson (played by James Stewart) as he searches for the elusive Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak) across San Francisco and the surrounding coastline. Due to debilitating bouts of agoraphobia, Scottie is at times unable to physically act or intervene as events unfold, with dramatic perspectival shifts in the camerawork emphasising the fragility of his mental condition.

Hitchcock’s symbolic use of architecture was developed further in North by Northwest, bringing high modernism to the screen as a cinematic language

Reviewing the film in 1958, The Los Angeles Times described Vertigo as ‘part thriller and part panorama’, acknowledging the director’s lingering, almost obsessive, gaze over the city. Hitchcock selected many of the locations before the script was completed, emphasising the importance of the vertiginous city to his narrative, as Scottie’s investigations take him to a series of major city landmarks. These include the dramatic Civil War-era Fort Point at the underside of the Golden Gate Bridge, the fine dining rooms of Ernie’s Restaurant on Montgomery Street and Podesta Baldocchi, one of the city’s oldest florists.

Midge’s apartment - Vertigo, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Paramount, 1958)

North by Northwest opening titles, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959)

An equally fastidious attention to detail was given to the film’s interior sequences. Each was shot on sets built at the Paramount Studios, but intricately planned and designed to further emphasise the roles of the individual characters in the plot. The grandiose wood panelled offices of shipping magnate Gavin Elster act as a theatrical stage, as the industrialist narrates to Scottie the tale of his wife Madeleine’s unusual behaviour. Scottie’s first sighting of Madeleine takes place in the plush setting of Ernie’s Restaurant, where the red silk walls instantly frame her as an object of his desires and mark the beginning of a descent into paranoia.

Across town, overlooking Russian Hill, the homely studio apartment of his fashion designer confidant Midge Wood offers a safe haven for Scottie from the unexplained events spiralling out of control outside. With her pastel yellow walls, George Nelson daybed and Harry Bertoia chairs, Midge (played by Barbara Bel Geddes, daughter of industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes) is presented as a character living very much in the present, a stark contrast to Scottie’s increasing obsession with incidents seemingly connected to the distant past.

Hitchcock’s symbolic use of architecture was developed further with his next film, North by Northwest, bringing high modernism to the screen as a cinematic language. Advertising executive Roger Thornhill (played by Cary Grant) becomes drawn into a complex tale of mistaken identity and stolen government secrets, pursed by a group of mysterious foreign agents across urban and rural America. As Thornhill finds himself in ever graver danger, Hitchcock uses a mixture of real and imagined American landscapes to heighten the suspense, concluding with a gunfight atop the Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota.

Vandamm House - North by Northwest, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959)

The film begins in New York and brings several notable modernist landmarks onto the screen, including Oscar Niemeyer’s newly completed headquarters for the United Nations. Equally contemporary was Harrison & Abramovitz’s CIT Building on Madison Avenue, finished in 1957, and presented here as the offices of Thornhill’s advertising company. The slick black granite and stainless steel facade was used by Hitchcock to capture reflections of the rush hour chaos of downtown Manhattan below, with the grid-like exterior also used as the template for Saul Bass’ iconic graphic identity and title sequences.

Hitchcock tasked production director Robert F Boyle with designing a residence that could imitate the eponymous style of Frank Lloyd Wright, then the most celebrated architect working in America

The film’s script also specified a series of purpose-built sets, including the famous mountaintop residence of the film’s nefarious villain, Phillip Vandamm. Hitchcock tasked production director Robert F Boyle with designing a house that could imitate the eponymous style of Frank Lloyd Wright, then the most celebrated architect working in America. With its bold horizontal projections, the exterior evokes Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece Fallingwater, while the interior is typical of his ‘Usonian’ housing concepts of the 1930s and 1940s, a simplified but modern American style, featuring informal open-plan living areas centred around a fireplace.

Yet despite the level of design detail, the house was was never actually built as a complete design. The interiors were built as separate stage sets, with Boyle and his production team painting the exterior views onto vast ten-metre-high matt canvas backdrops, which was later cut into separately filmed sequences of Cary Grant. The exaggerated concrete cantilever of the house, extruding high out over the mountain, is matched by the deliberately angular perspective of the camera’s viewpoint, building tensions as the film nears its climatic conclusion.

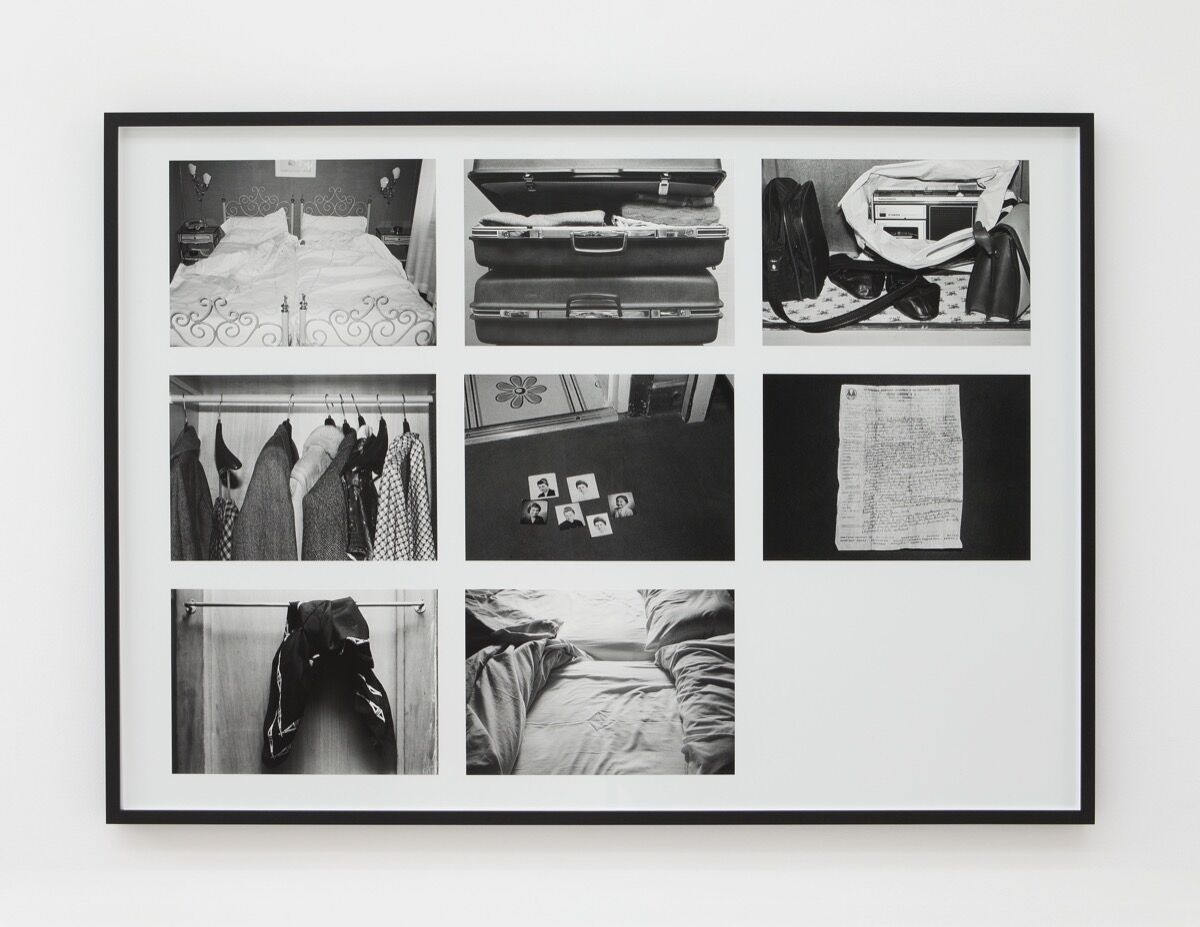

United Nations Headquarters - North by Northwest, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959)

Similar matt painted backdrops were needed to replicate the interior of Oscar Niemeyer’s United Nations Headquarters. Despite Hitchcock’s high profile and a production budget of $3 million ($25 million today), permission was refused to film inside or outside the recently completed modernist masterpiece. Instead, views of the building’s interior were painted as backdrops, with the brief exterior scenes shot clandestinely. A van housing a hidden camera was parked across the street, and using a long lens the team was able to capture the actors as they performed with the unwitting public walking around them.

North by Northwest is perhaps the definitive expression of high-modernism seen in Hitchcock’s films. Robert J. Boyle was nominated for an Academy Award for his work on the production design and would later collaborate again with the director for The Birds, creating the gloomy, seaside atmosphere of Bodega Bay onto which horror descends from above. Throughout the initial storyboarding and production design process Boyle kept an image of Edvard Munch ‘The Scream’ in mind as his main point of reference.

Vertigo, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Paramount, 1958)

Vertigo, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Paramount, 1958). Image courtesy of Park Circus/Universal

Hitchcock’s next project was Psycho, a return to the voyeurism of his earlier film Rear Window but with murderous consequences. In contrast to the wide open panoramas of North by Northwest, Psycho is shot predominantly in close-up, creating terror through the simple reframing of mundane domestic spaces. The contrast between the anonymous but functional architecture of Norman Bate’s motel and his mother’s crumbling gothic house on the hill above, symbolises his split personality, yet one that is revealed only incrementally.

Such sequences reveal the mastery of Hitchcock’s films, by deliberately keeping dialogue to a minimum, tension is built instead through the gradual revealing of information and events, but dictated by the layout of the buildings themselves. For Rear Window, an everyday Greenwich Village city block is visible only through the limited perspective of the windows in the apartment opposite, becoming the sole means by which we understand the events glimpsed from distance, altering the mood significantly.

Vertigo, dir: Alfred Hitchcock (Paramount, 1958). Image courtesy of Park Circus/Universal

The influence and legacy of Hitchcock is visible throughout cinema history. His masterful use of architectural space can be seen in the empty yet haunting corridors of the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, and the rainy, future-noir Los Angeles portrayed in Ridley Scott’s Bladerunner, a city of cavernous monolithic structures rising above crumbling street level apartments. More recently the enfolding architectural mazes created for the multiple dream levels of Christopher Nolan’s Inception and Wes Anderson’s obsessive interior styling in The Grand Budapest Hotel both owe a debt to Hitchcock’s ability to make architecture speak as loudly as the actors. §