|

What Opera Might Be

Ahead of its South London Gallery performance, how Tom Phillips’s Irma – a work that questions the genre of opera itself – is being staged

Ahead of its South London Gallery performance, how Tom Phillips’s Irma – a work that questions the genre of opera itself – is being staged

Just over 50 years before its performance at the South London Gallery this September, Tom Phillips's Irma: An Opera (1969/2014) was a dusty, non-descript Victorian novel in a Peckham flea market, a mile or two down the road. In the late 1960s, London's culture of experimental art and performance was thriving, with practitioners and audiences sliding fruitfully between old disciplines and institutions in ad hoc spaces among the city's 19th-century suburbs. A seemingly limitless creativity was opening up in the wake of the increasing influence of John Cage, William Burroughs, and more, and often it was given a peculiarly English twist of modesty, humour and historicism. All of this was demonstrated when Phillips, accompanied by his friend, the artist R. B. Kitaj, found himself browsing second-hand books and wagered that 'the first book I can find for threepence I'll work on for the rest of my life.'

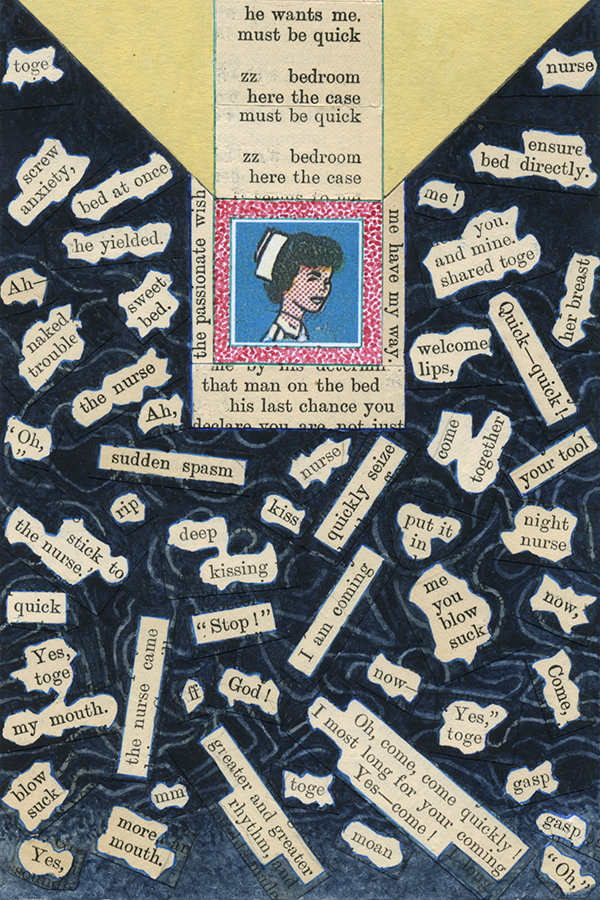

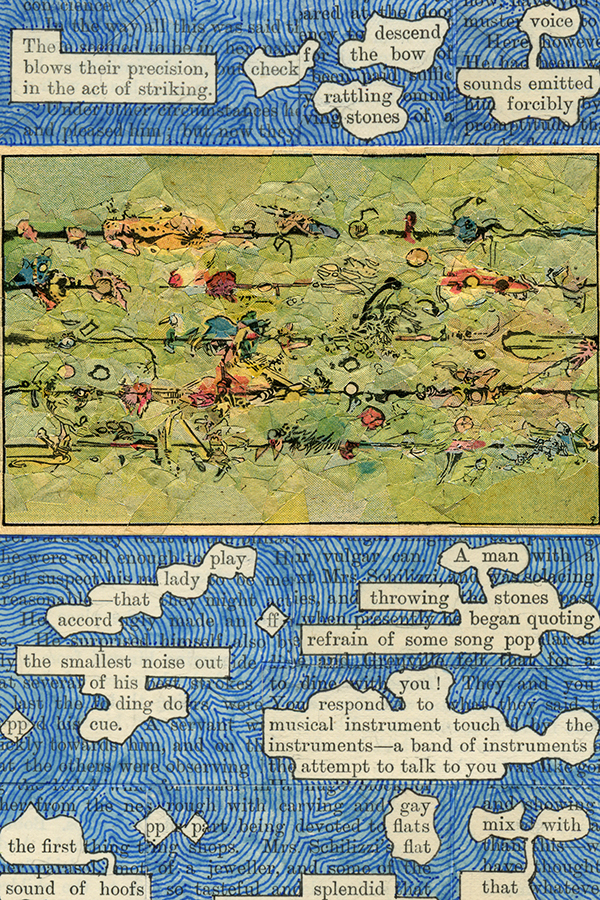

The book was the largely unremarkable 1892 romance A Human Document by William Hurrell Mallock, and Phillips went about treating it, shuffling it and adorning its pages with a quiet tenderness over a period of 50 years. The result is his magnum opus A Humument (1966–2016). The first volume was produced in 1970 and the sixth and final one appeared last year. One of the hallmarks of A Humument is Phillips's technique of isolating certain words on the page and painting over the rest, enabling a beguiling poetry to rise out. But it is not just concrete poetry, or even the visual field as a whole, that Phillips is concerned with. He soon created Irma Opus XII (1969), a large single-page score for an opera on which directions for libretto, mise-en-scène and sound were generated by that same technique of serendipitous word-finding. This was recently expanded into a score of 119 pages, again deriving from A Humument, and dubbed Irma Opus XIIB (2014).

The task of realizing such an elaborate graphic score fell to director and designer Netia Jones, together with her company Lightmap, and Anton Lukoszevieze and his ensemble Apartment House. The world premiere of Irma Opus XIIB at South London Gallery this weekend celebrates Philips's 80th birthday and the completion of A Humument. 'I am moved by the very fact of it now being finished, the idea that a life's work can come to some kind of completion,' says Jones. 'And yet of course, it will always live on because [Tom has] left it wonderfully open-ended. As a gesture, that's very beautiful.' Part of the intrigue of the graphic scores that sprang up in the 1960s is their open-endedness in relation to resulting sound – the most alluring ones don't make the task of generating sound more exact, but its possibilities more inspiring.

Jones and Lukoszevieze transformed the poetry of Irma Opus XIIB into libretto, music, characters, dance, decor, costumes, pre-recorded sound and video. Doing so involved plumbing the layers of history: the present, the 1960s, and the late Victorian origin, which finds another echo in the space and architecture of the South London Gallery. 'I felt like an archaeologist,' Lukoszevieze told me. 'All these fragments in the score, bits and pieces of material and suggestions for what could be in it.' Noticing a focus on time and timepieces in parts of the material, Jones and Lukoszevieze decided to lay a 60-minute timeline as a foundation, with performers referring to clocks throughout for orientation. They then decided to unfurl this time palindromically, inspired by one of Phillips's images: 'everything that happens in the first half happens backwards in the second half,' observes Lukoszevieze.

One of the more suggestive lines in the score is 'art officers in uniform, illuminated' – this was expressed as a Greek chorus of three sharp-suited men observing and judging the action. At the centre of it are Grenville and Irma, names appearing in Mallock's original text, as well as a nurse and Toge, a surrogate for Phillips himself, who reads his text on recordings played back during the performance. Jones discovered A Humument when she was 13 and has heard Phillips reading from it many times. 'For me it was very important to have Tom's voice as a central part,' she says. 'He reads it in a very particular way, of course he does, because he's lived with it every day.'

Diverse and open, as a work Irma begins to question the genre of opera itself, something which Phillips, Jones and Lukoszevieze weave in as a wry self-awareness about operatic tropes. Like many operas, it is named after a woman, it has pastoral and drinking scenes, even a waltz derived from a 19th-century example that Phillips cut-up and re-ordered. Jones doesn't see it as an opera – 'I see it as something that's about opera, or the idea of what opera might possibly be.'

Lukoszevieze goes further: 'No one knows what an opera is. The idea of opera most people have is a 19th-century construct. There has to be a stage, with curtains and proscenium arch and orchestra. The original Latin word just means ‘work’, it just means putting things together.'

The word gesamtkunstwerk – describing a work in which every form and medium of art is employed and determined – has reached the point of cliché, but it's worth remembering that it was first used to describe opera, specifically, those of Wagner. Jones sees Phillips as 'the archetypal cross-media artist – he doesn't even see the boundaries between art forms.' As a result, Phillips has been slow to gain the recognition that many of his monomedia contemporaries have. The rich aesthetics and histories of opera – whatever opera is – provide the ideal site to encounter a figure who has played a part in many aspects of postwar British creativity, from graphic design to film. But Phillips is no Wagner: rather than trying to be the absolute ruler of the gesamtkunstwerk, Phillips is a connecting node between disparate strata of the past and present and all the scatterings of creativity among them. As Jones puts it, his task, and that of those adapting it, is to 'open up as much interpretive space as possible.' Just as Phillips curates Mallock's texts, so Jones and Lukoszevieze and their teams (and the audience, ultimately) curate his.

Performances of Tom Phillips’s Irma: An Opera at South London Gallery, 16-17 September 2017, are sold out – the audio-visual installation during the day, animating the score through soundscape and video works, is free to enter.

Main image: Tom Phillips, Irma Opus XIIB, 2014, detail from score. Courtesy: the artist and Flowers Gallery