How Art Has Depicted the Ideal Male Body throughout History

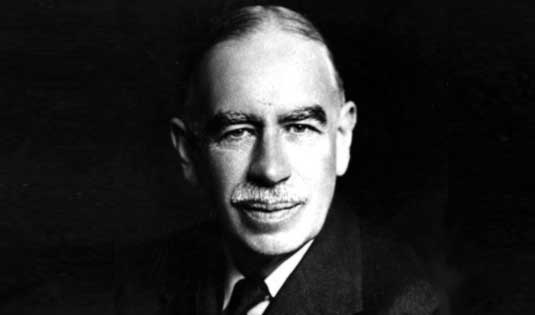

In the history of masculinity, it is money rather than muscle that tends to be articulated. Class or status has been the determining factor in the defining of male exemplars. Be it in the East or West, the epitome of a handsome man has generally been an idealized version of an upper-class individual, an archetype that has itself changed over time.

Because of this, people in many cultures have confronted muscle—today more commonly understood as a symbol of virile masculinity—as a problem. For much of history, muscles have been seen as vulgar, meaty indicators of labor; rather than strength they have suggested oafishness or, at best, potentially deviant self-regard.

Even today, we’re not clear on whether muscle is an indication of health or narcissism, menace or manliness. (And on women, they present a whole other set of problems.) The ideal man—the gentle-man—has no muscles because he does no physical work; he is also pale, because he has not toiled in the sun; and he is tall because he is well-nourished.

It’s a type that began to take shape in early 19th-century Europe, in England in particular, and held sway until very recently. Despite the more developed physiques found in Tarzan or James Bond films, athleticism has been far less esteemed throughout history than a body formed by ease, alcohol, and cigarettes. And while the first mass fitness revolution occurred in the early ’70s, the masculine figure it celebrated—the thin, jogger’s frame—remained aesthetically identical to the old upper-class ideal, if perhaps a bit less winded.

Things began to change only around 2000, with the proliferation of access to information about health via the internet. Today, the cost of access to the highest-quality food and gyms, as well as to the best information about how both ought to be used, has spiked. As a result, privilege is signified by figures with low body-fat percentages that showcase taught muscles, by the leisure to afford long workouts in expensive gyms, by eating regimens crafted by coaches and trainers, by tans that bespeak travel, and by fitted, expensive clothing that accentuates these advantages. The greatest attitude shift, however, has been toward beefcake.

The notion of muscularity was reintroduced to the world in the mid-16th century, with the discovery of what came to be known as the Farnese Hercules, a Roman copy of an ancient Greek sculpture. But, it had an extremely limited influence until the current era. Only after the myths surrounding muscle—that it contributed to heart disease, made one slow and inflexible, and was not something produced through training but was instead a God-given marker of a low caste—were debunked did it become a marker of health and prosperity.

Oddly enough, the withering of gender stereotypes was just as powerful a filter in changing how male bodies are seen. As the vilification of homosexuality became less intense, male bodies were increasingly sexualized—and men’s attention to their appearances became acceptable. All forms of male self-fashioning—from building muscle to sartorial extravagance to grooming—have become not just socially accepted but expected.

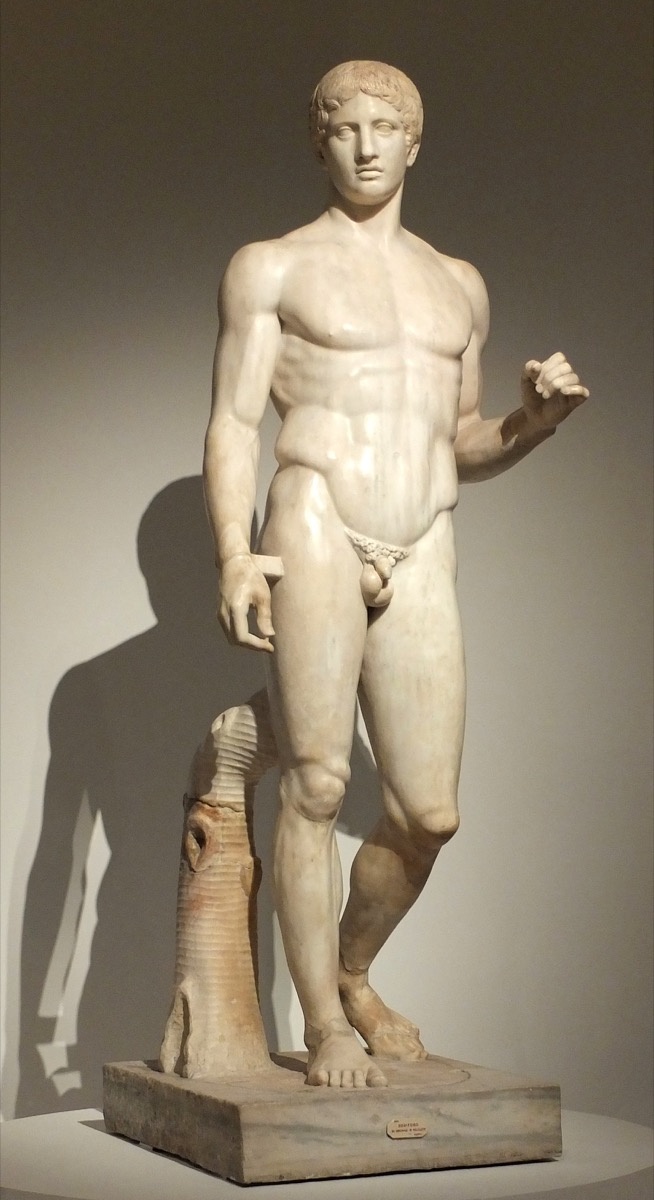

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), Roman copy of 440 BCE Greek original. Archaeological Museum of Naples, Pompeii. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), Roman copy of 440 BCE Greek original. Archaeological Museum of Naples, Pompeii. Via Wikimedia Commons. Yashima Gakutei, Three Great Wise Men of the Han Dynasty, 19th Century. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Yashima Gakutei, Three Great Wise Men of the Han Dynasty, 19th Century. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Doryphoros, Polykleitos, circa 440 B.C.

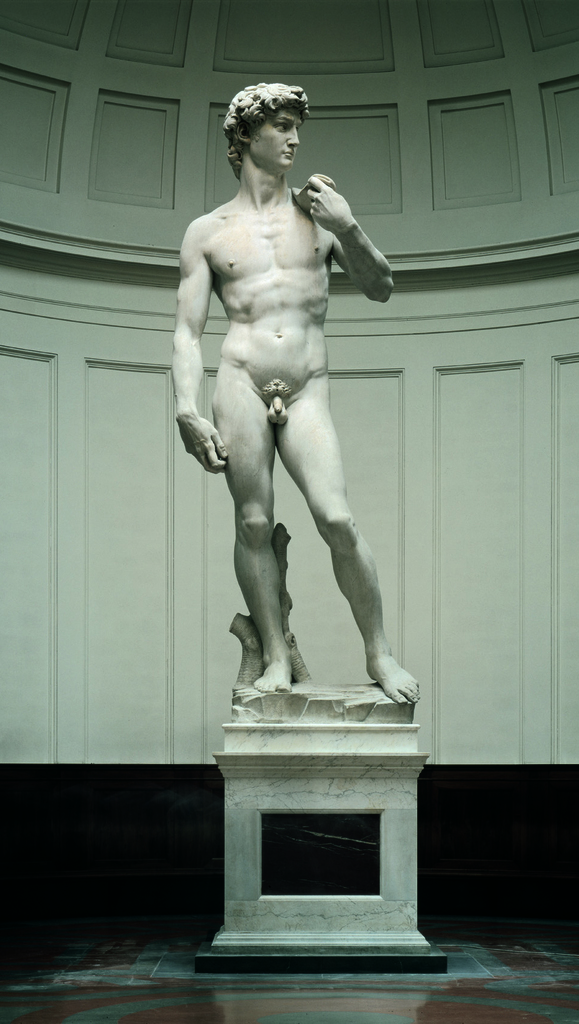

Along with similar ancient Greek statues of warrior-athletes, the Doryphoros, or “Spear-Bearer,” established a standard of male beauty that abides today in the West: the muscular, athletic mesomorph. Although common in art—from Michelangelo’s David (1501–1504) to Arno Breker’s fascist sculptures—the physique depicted was considered unattainable until very recently.

Chinese aristocrats, Later Han Dynasty, A.D. 25–220

In traditional Chinese paradigms of masculinity, the concept of wen (literary and cultural achievement) exists inseparably paired with wu (physical and martial acumen). Nonetheless, wen has been seen as more elite and has predominated since at least the middle of the Han Dynasty. The value of stillness superseded that of action, while physical activity was regarded as ungentlemanly.

Andrea di Bartolo, The Crucifixion [reverse], 1415

The advent of Christianity in late antiquity saw a valorization of spiritual over worldly values. Emaciation signified a pious denigration of the flesh, and the rigors of attaining it made the devotee an “athlete for Christ.” That wasting, otherworldly aesthetic recurs somewhat cyclically, popping up, for instance, among hippies in the 1960s and in the heroin chic of the early 1990s.

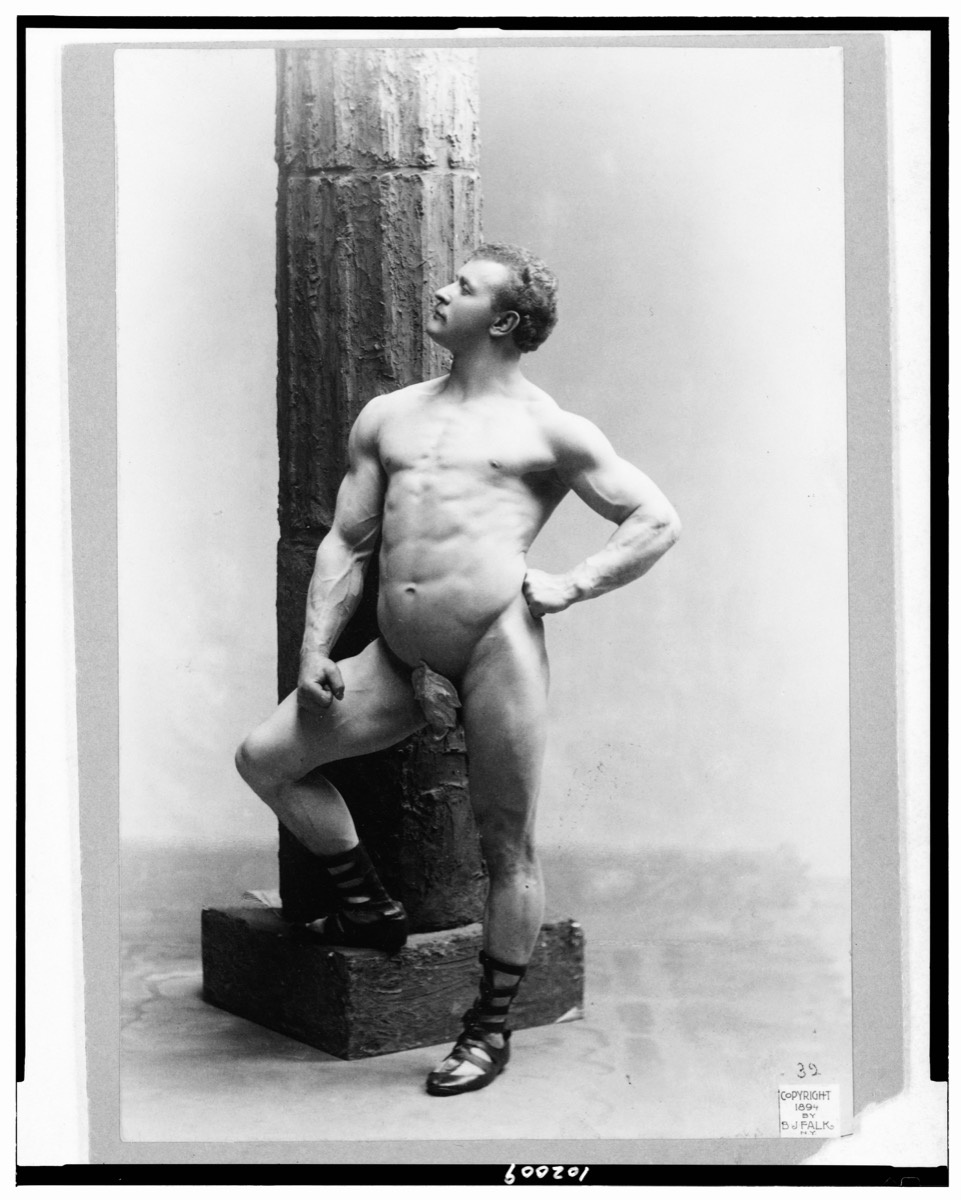

B.J. Falk, Eugen Sandow, full-length nude portrait, standing by column, facing left, 1894. Copyright by B.J. Falk, N.Y. Courtesy of The Library of Congress.

B.J. Falk, Eugen Sandow, full-length nude portrait, standing by column, facing left, 1894. Copyright by B.J. Falk, N.Y. Courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Donatello, David, 1428–32

Alongside, or perhaps in opposition to, the image of the hairy, testosterone-fueled muscleman stands a softer icon. As Donatello’s sculpture argues, a male with feminine graces can be both heroic and beautiful. That more effeminate model has had its artistic champions throughout history, from the figure of Endymion to androgynous rockers of the ’70s, to the photographs of Ren Hang.

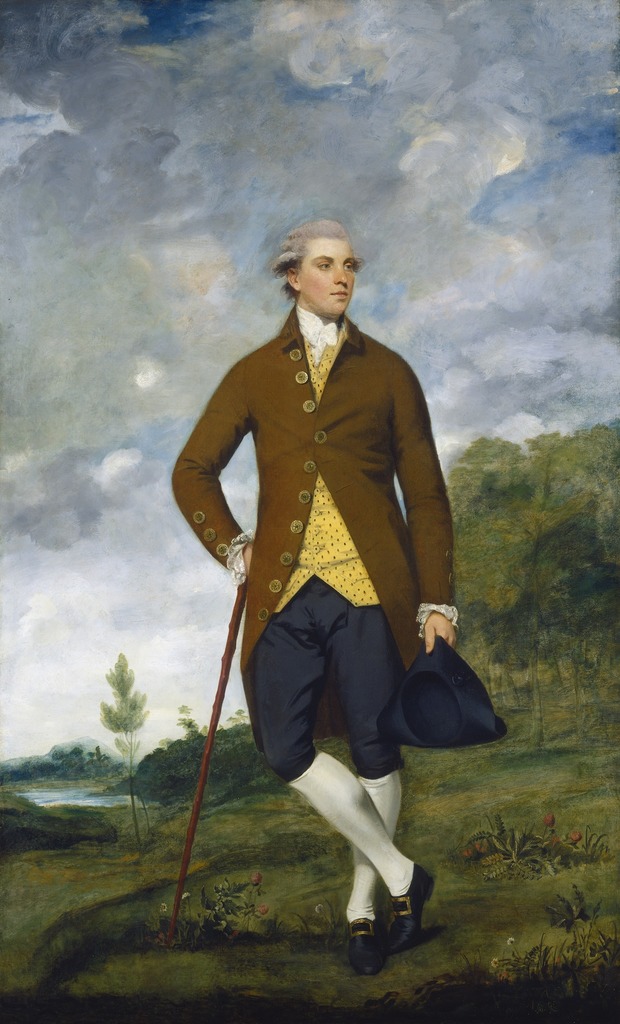

Sir Joshua Reynolds, John Musters, 1777–c. 1780

Masculine beauty in the 18th century, as in the 16th and 17th centuries, was expressed in adornments—an attractively patterned waistcoat, a finely coiffed wig—more than through physical attributes. However, there are exceptions. In the age of horseback riding, tight pants showed off well-turned legs and fine hips, for instance.

B.J. Falk, Eugen Sandow, full-length nude portrait, standing by column, facing left, 1894

A German strongman, Sandow uniquely became known more for his physique than for feats of strength. In 1894, he posed for one of the world’s first commercial film strips, which was produced by Thomas Edison, and in London seven years later he mounted the world’s first bodybuilding contest. It would, however, take some three-quarters of a century before male preening became acceptable to the wider culture.

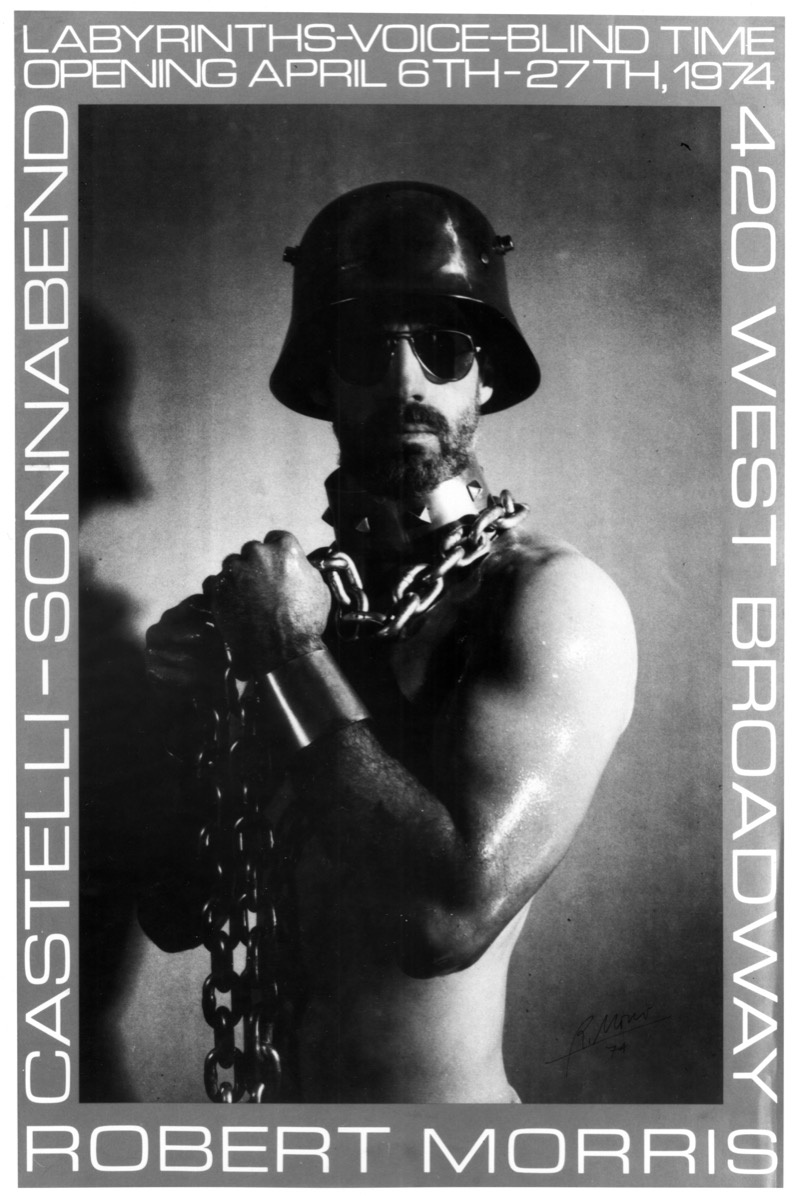

Robert Morris, Castelli-Sonnabend poster, 1974. Courtesy of Castelli Gallery.

Robert Morris, Castelli-Sonnabend poster, 1974. Courtesy of Castelli Gallery.

Slim Aarons, Prince Philip Receives Windsor Cup at Ascot Polo Tournament, 1955

For more than two centuries, the traits associated with the European aristocratic man have been held up, whether consciously or not, as the sex’s most desirable. Thus, Humphrey Bogart, playing a down-and-out detective in the 1946 film noir The Big Sleep, looked more like a prince than a palooka. Here Prince Philip exemplifies the look: Thin, though hale, with the narrow chest and spindly arms of a man unaccustomed to lifting much more than a silver cigarette case.

Robert Morris, 1974 poster for Castelli show

The Castro clone look, which sprang up in mid-1970s San Francisco, valorized such working-class attributes as facial hair, blue jeans, leather jackets, and muscles. Although the clone look ought to be seen within the context of a growing, culture-wide appreciation of the working class at the time, it also marks an initial instance of public sexualizing of male bodies.

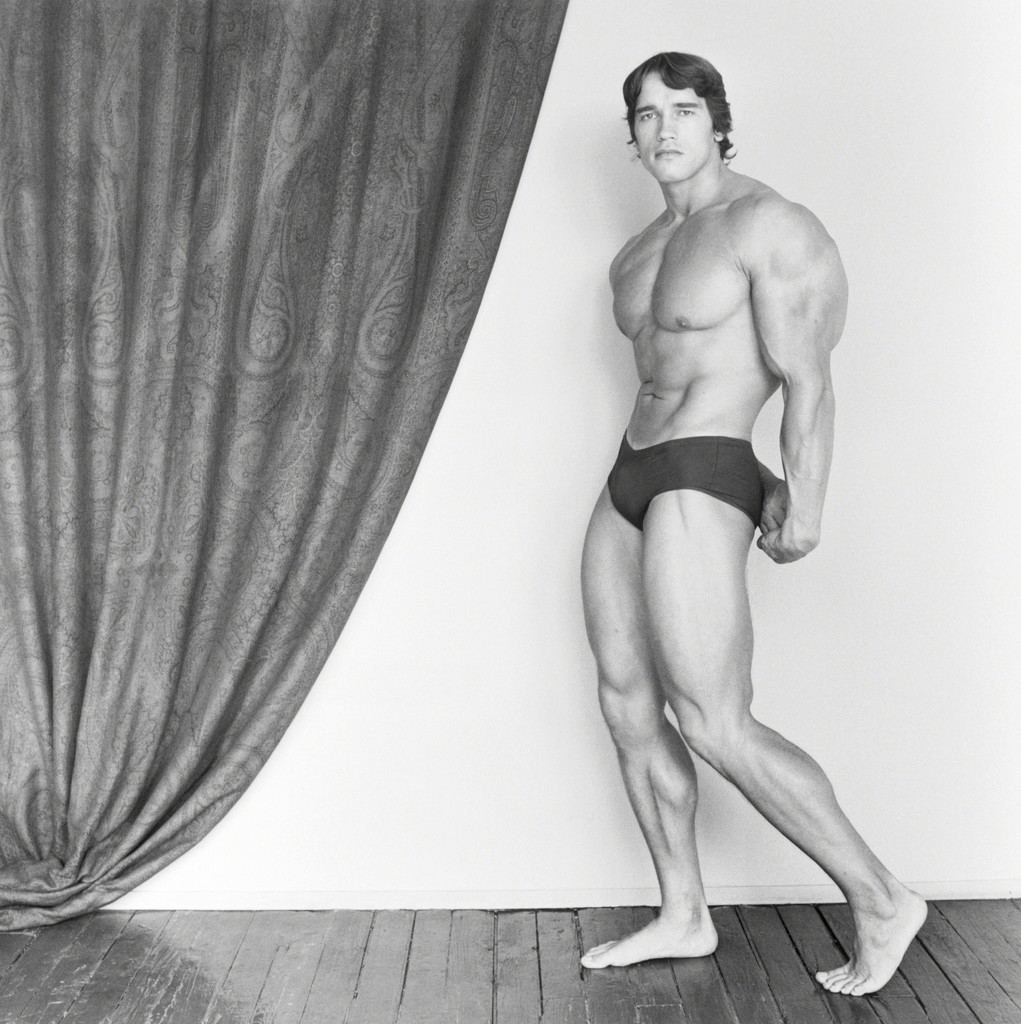

Robert Mapplethorpe, Arnold Schwarzenegger, 1976

Bodybuilding was brought to the broader public consciousness by Schwarzenegger and the 1977 film Pumping Iron. It offered an ideal of exaggerated musculature that was obviously unattainable, no matter how much effort one put in, without technological enhancement in the form of steroids and specialized weight machines.

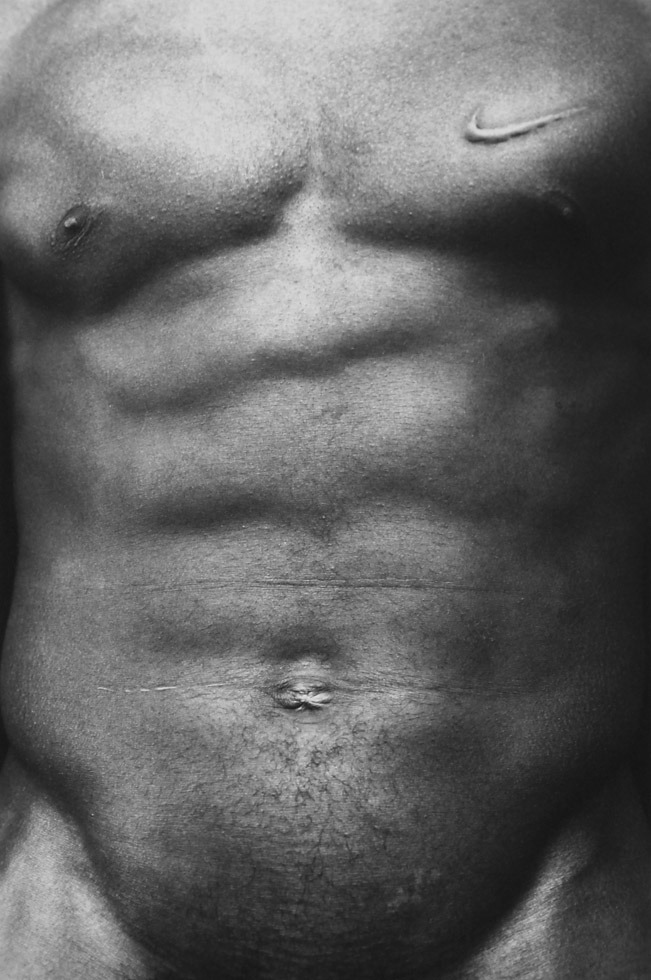

Hank Willis Thomas, Branded Chest, 2003

While today’s muscular ideal harkens back to the Doryphoros, with its athletic figure, it has expanded to include men of all skin colors, races, and ethnicities. But, as Thomas’s work suggests, such bodies are increasingly branded—made dependent on various corporate entities, owned and exploited by them for the information the body contains, or objectified and marketed by us through social media, among other distribution systems.

Frank Benson, Juliana, 2014–15

Does the penis make the man? Benson’s sculptural depiction of the trans artist Juliana Huxtable illustrates just how blurry the sharp distinction between male and female has become. While some traditionally male features remain, like confidence, alongside traditionally female ones, like grace and smoothness, the work suggests that agency, the power to create oneself, has become the supreme ideal.

—Daniel Kunitz