|

|

|---|

Rome’s Newly Reopened Museum of Civilizations Is Decolonizing Its Collection. It Is a Rare Success Story

The institution, designed during the reign of totalitarian leader Benito Mussolini, carries heavy histories within its walls.

Following a six year renovation and, more significantly, a pivotal redo, Italy’s Museum of Civilizations reopened its doors to the public on October 26. In recent years, many encyclopedic museums around the world began to anxiously tackle the ideologies and modes of presentation behind their ethnological collections—not to mention their often spotty provenance. Rome, which has been slow to confront its colonial past in the public discourse, is decolonizing the state-owned museum’s collection with remarkable clarity of vision, steered by Italian curator Andrea Viliani.

Having taken up the directorship of the Museum of Civilizations (known in Italian as the Museo Delle Civilta) only this past March, Viliani didn’t waste any time implementing a “progressive radical revision process” that will unfold over the next four years, as different collections in the museum’s holdings will gradually reopen to the public.

The encyclopedic collection counts over two million items and documents that came under one roof as the result of merging several state collections that have been closed to the public for years. It includes prehistoric artifacts, paleontology, and mineralogy collections, as well as items representing Italian folk traditions, ethnological collections, and the collection of the former Colonial Museum of Rome, which was inaugurated by Mussolini in 1923. The latter will most likely prove most challenging to study, as the Colonial Museum never used scientific methods of archiving and cataloguing, nor has it kept the biographies of the objects it had amassed.

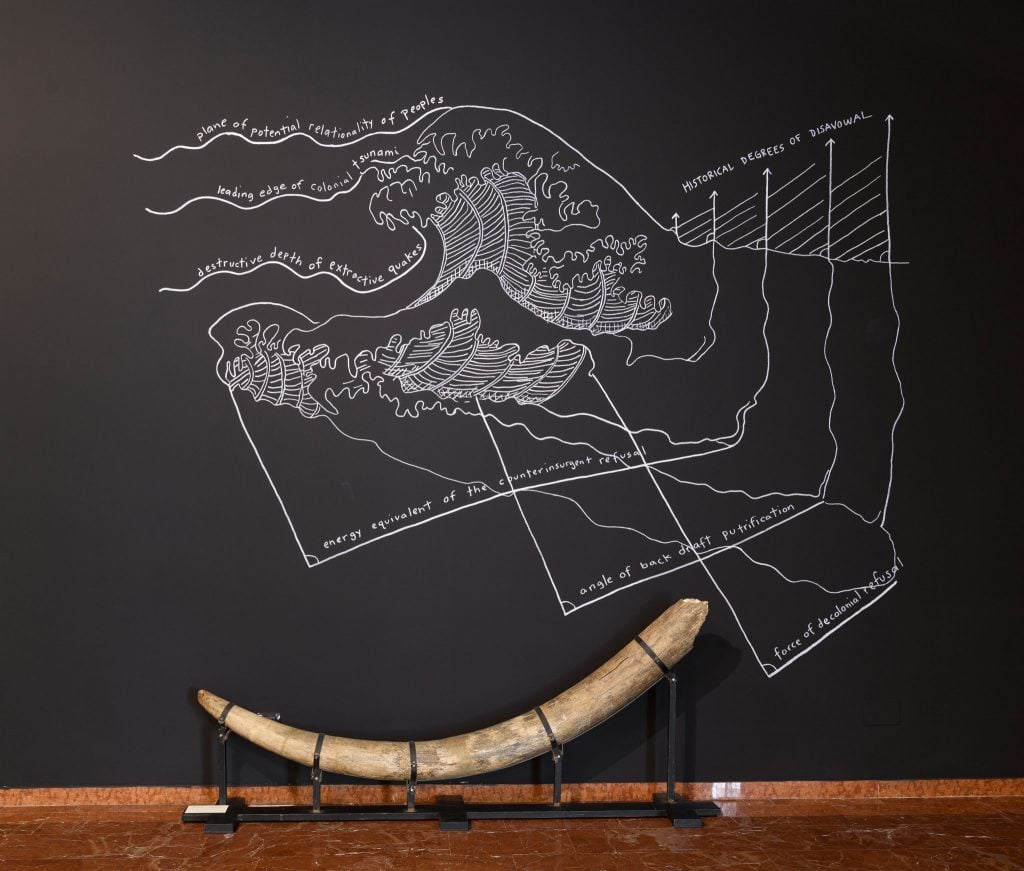

Museum of Civilizations, Rome. Installation view. Photo: Giorgio Benni. Courtesy Museum of Civilizations

For Viliani, an erudite, soft-spoken force of nature, the most coherent way to present and contextualize the vast holdings was self-evident. “The museum should tell the stories of how human beings related to each other, sometimes respectfully, sometimes disrespectfully, violently, and in self-destructive ways for society and the planet. And to show that it happened everywhere, all throughout history,“ he told Artnet News. But there’s also another, parallel story. “The projects of encyclopedic and anthropological museums started in the 19th century, from a positivist, Eurocentric culture driven by ideas of dominance,” he added. “We need to tell these paradigms as well, in particular because it happened at the same time as the unification of Italy, as the new nation was born.”

Viliani is rethinking the museum within the specific context of Italian history, and the othering that helped to shape a nascent national identity. But one chapter of Italian history looms particularly large. The multi-part museum is located in Rome’s EUR district, a sprawling marble-and-concrete “model city” built by Mussolini to glorify the fascist project and house the 1942 World Fair, which never took place due to World War 2.

Frescoes of Palazzo delle Arti e Tradizioni Popolari (EUR, Roma). Photography Courtesy Museo delle Civiltà, Roma / Museum of Civilizations, Rome. Photo © Corrado Bonora

Back in March, when the team of researchers and curators got to work, no one could have known that the museum’s reopening would coincide with the beginning of another troubling chapter in Italian politics. It came as no surprise that Italy’s New Culture Minister, Gennaro Sangiuliano, didn’t attend the grand opening.

But Massimo Osanna, who is director-general of all Italian museums, working within the ministry of culture since 2020, was beaming at the press preview. Asked how the new government (which is not the one that appointed him) might respond to the museum’s progressive overhaul, he replied that “it‘s important to include different points of view in every museum because culture is not monolithic. Culture is fluid, it’s a process of hybridization,” he told Artnet News. “It’s wrong to think there is one true point of view.”

View of Piazza Guglielmo Marconi (EUR, Rome). Photography Courtesy Museo delle Civiltà, Roma / Museum of Civilizations, Rome. Photo © Andrea Ricci

The Role of Contemporary Art in Showing Multiplicity

Osanna stressed the importance of contemporary art in shaping the museum’s approach, and illuminating the many narratives connecting past and present. To that end, curator Matteo Lucchetti joined the museum‘s team as head of contemporary art and programs after nearly a decade abroad working with artists such as Sammy Baloji and Otobong Nkanga, who deal in their art with colonial legacies and extractive industries.

Lucchetti invited six artists to act as research fellows and develop longterm, autonomous projects around the museum’s archive and collections, in addition to the scientific and provenance research that’s taking place. “As long as the museum is changing, these changes will be accompanied by contemporary interventions.” said Lucchetti. Rather than highlighting contemporary work commissions, which could appear as if the institution attempted to “artwash” its collection, Lucchetti is taking a nonhierarchical approach where old and new are integral to the museum’s identity. “It’s a site-specific contemporary collection which is a byproduct of the role of contemporary art in the research,” he told Artnet News.

Among the fellows are Maria Thereza Alves, Sammy Baloji, DAAR-Decolonizing Architecture-Art Research (Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti), Bruna Esposito, Karrabing Film and Art Collective, and Gala Porras-Kim. Works giving insights into their practice and approach to the collection were installed in the building’s massive, marble-covered entrance. There, the curator also included photographs and pieces that refer to the museum’s architecture and location in the district of EUR. A work by Peter Friedel titled Tripoli (2015), shows a model of the Fiat factory that was meant to be built in Tripoli, Libya, under Italian colonial rule in the early 20th century, part of his research that looks at the connections between modernity, fascism, and colonialism.

Museum of Civilizations, Rome. Installation view Photo: Giorgio Benni. Courtesy Museum of Civilizations

What Came Before History?

Upstairs, visitors can view the prehistoric collection, which is the first to have been rehung and recontextualized. (Next up is the geological collection, set to open in mid-December under the title “Animals, Plants, Rocks and Minerals—Steps to a Multispecies Museum.”) Even the very use of the term “prehistoric” was put into question: Why do we mark the beginning of history with the first records of written language? Aren’t the traditions, artifacts, and rituals whose material evidence is stored here deserving of a non-prefixed term?

With more than 150,000 artifacts, the Museum of Civilizations preserves Italy’s largest collection of findings from archaeological sites dating from the Stone Age to the earliest forms of writing. The new display exhibits items that haven’t been accessible to the public before, such as the Guattari 1 Neanderthal skull found in Circeo; the three fertility “Venuses” found in Italy’s Savignano, Lake Trasimeno, and La Marmotta sites; and the gold Praeneste fibula bearing one of the oldest examples of Latin writing, which brings the tour to a close.

Museum of Civilizations, Rome. Installation view Photo: Giorgio Benni. Courtesy Museum of Civilizations

Here, Lucchetti invited the indigenous group Karrabing Film Collective’s Italian member Elizabeth A. Povinelli, a trained anthropologist, to add contemporary thinkers and texts to the displays. A quote by scholar Kathryn Yusoff for example reframes the anthropocene (a geological epoch that begins with humanity’s impact on Earth ecosystems) as “a politically infused geology and scientific / popular discourse just now noticing the extinction it has chosen to continually overlook in the making of its modernity and freedom.”

Elsewhere, visitors are offered more visual experiences of the same criticality. Lebanese artist Ali Cherri’s video work The Digger (2014) is installed within the prehistoric presentation. It shows an archeological excavation in the Emirates, and the person doing the digging is a worker from Pakistan. It speaks to one of Lucchetti’s aims with the rehang, which he said is to “to stress” that “behind the creation of a historical collection there was a declaration of a national identity through othering.”