Art World

The Carnegie Museum Discovers a Forgotten George Romney (and Other Treasures) Hiding in Its Storage Vault

The museum's thrilling findings are the subject of a new exhibition.

More than a dozen works in the Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection are the subject of new attributions or major new discoveries following a marathon research initiative. Three years ago, the 120-year-old Pittsburgh museum decided to hunt through its vaults to re-examine works from the Enlightenment era that had rarely been shown.

The results are, well, enlightening. A number of objects have been re-attributed, including one painting now confirmed to be by the celebrated English portrait painter George Romney. That work, along with dozens of others, will be shown for the first time in decades in the exhibition “Visions of Order and Chaos: The Enlightened Eye,” which opens at the Carnegie on March 3.

“We’ve got all these interesting paintings that have not been properly appreciated,” Louise “Lulu” Lippincott, the Carnegie’s curator of fine arts, tells artnet News. She explains that the institution’s earliest holdings are heavy on British portraiture because Gilded Age collectors in Pittsburgh took cues from the wealthy Mellon and Frick families, who were also buying them.

But “as the works went out of fashion, they went off view,” Lippincott says. “A great many things just sort of disappeared into storage.”

The prolonged research effort involved investigations into “condition, provenance, conservation, and interpretation of the meanings of some works,” she says. Some of the new discoveries were exciting, while others—like the downgrading of a work originally believed to be by British artist John Hoppner—were deflating.

“The good thing is that because we’re a museum, the impact on value is not a primary consideration,” Lippincott says. “We are mostly interested in getting it right, even if it means that the name of the artist is not as prestigious or valuable as before.”

Below, Lippincott walks us through some of the Carnegie’s most consequential new discoveries.

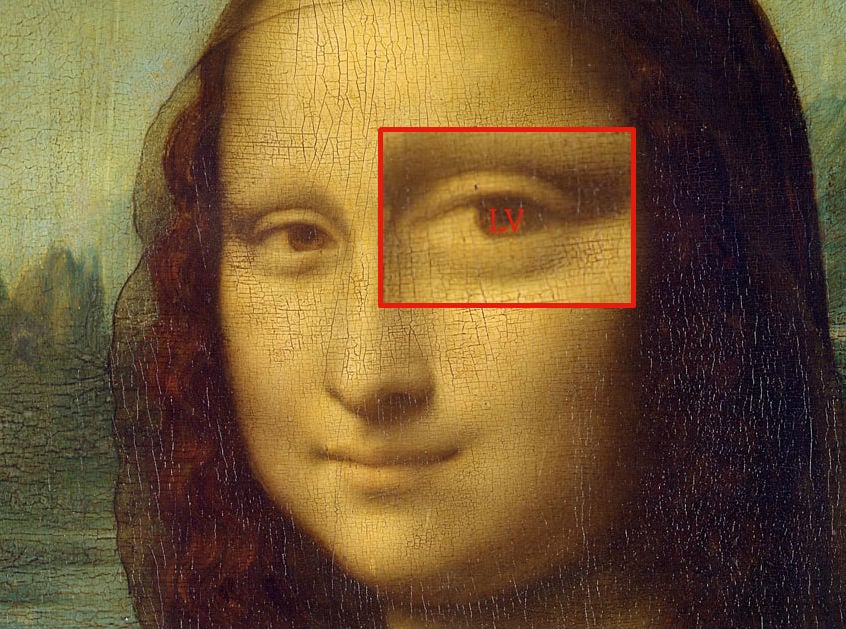

A Romney Work Hiding in Plain Sight

Carnegie experts long believed that this painting (above), one of many in storage, was by the British portraitist Francis Cotes. So when the author of the catalogue raisonné for the far more renowned British painter George Romney asked the curators for a rundown of their Romney holdings, they didn’t even consider sharing this one. Later, when the Romney catalogue raisonné was published, they spotted a familiar image: their very own “Francis Cotes” painting. While the catalogue had marked the location of the work “unknown,” the Carnegie knew just where it was—sitting in its own storage unit.

Further research allowed the museum to “very securely” confirm it was an early work of George Romney, Lippincott says. Furthermore, researchers were able to re-identify the sitter as a relative of the person it was originally thought to depict.

Dashed Hopes for Hoppner

John Hoppner, Miss Home with Kitten (circa 1795). Carnegie Museum of Art, J. Willis Dalzell Memorial Collection, gift of Mrs. J. Willis Dalzell

Not every new attribution has been an upgrade, however. Museum officials originally believed that this 18th-century portrait of the adorable Miss Home and her furry feline was the work of celebrated English portrait painter John Hoppner. While conducting research on the work ahead of the show, an expert uncovered handwritten notes from esteemed art historian Sir Ellis Waterhouse, who had long ago cast serious doubt on that attribution. Now, the Hoppner name is officially followed by a question mark. However, there is no doubt that the portrait of Master Order (below) is the real deal.

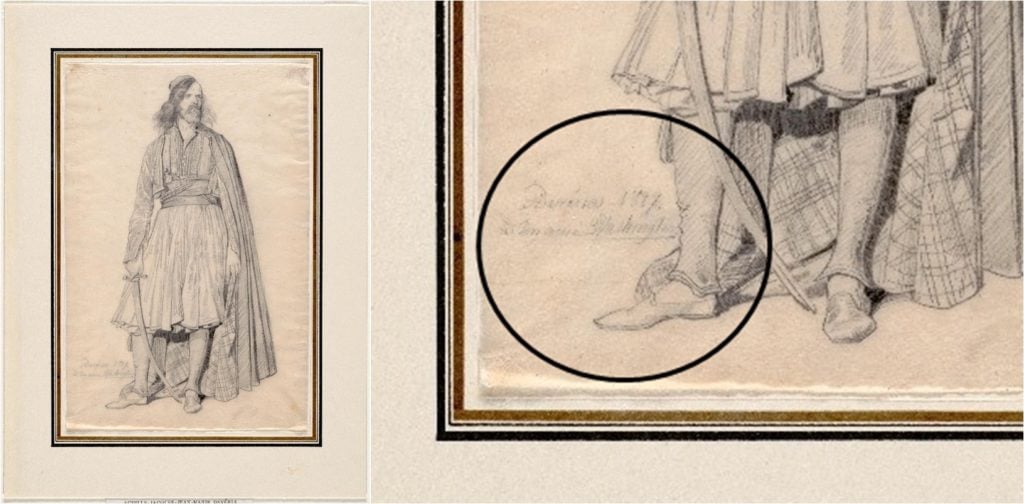

A Potentially Famous Original Owner of This Ghostly Tracing

Achille Devéria, Soldat Souliote (Souliote soldier) (1827). Graphite on translucent paper

Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Daniel Fishkoff

Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Daniel Fishkoff

French artist Achille Devéria’s tracing of his original drawing of a Greek freedom fighter (circa 1826–7) has long been part of the Carnegie’s collection. (The Louvre owns the original.) The Carnegie’s version on translucent paper bears an inscription on the lower left that reads: “A mon ami Washington… [to my friend Washington…].” Now, experts have set out to confirm the identity of the mysterious “Washington.”

They suspect it could be the American writer Washington Irving, who was in Paris serving as a diplomat at the time. He was also known to be a major supporter of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire, which would make a drawing of a freedom fighter a fitting gift. But while Lippincott says “it’s possible” the Washington referred to in the note is Irving, only further art historical sleuthing will prove it for sure.

French artist Achille Devéria’s drawing and detail of signature, right. Courtesy of the Carnegie Museum.

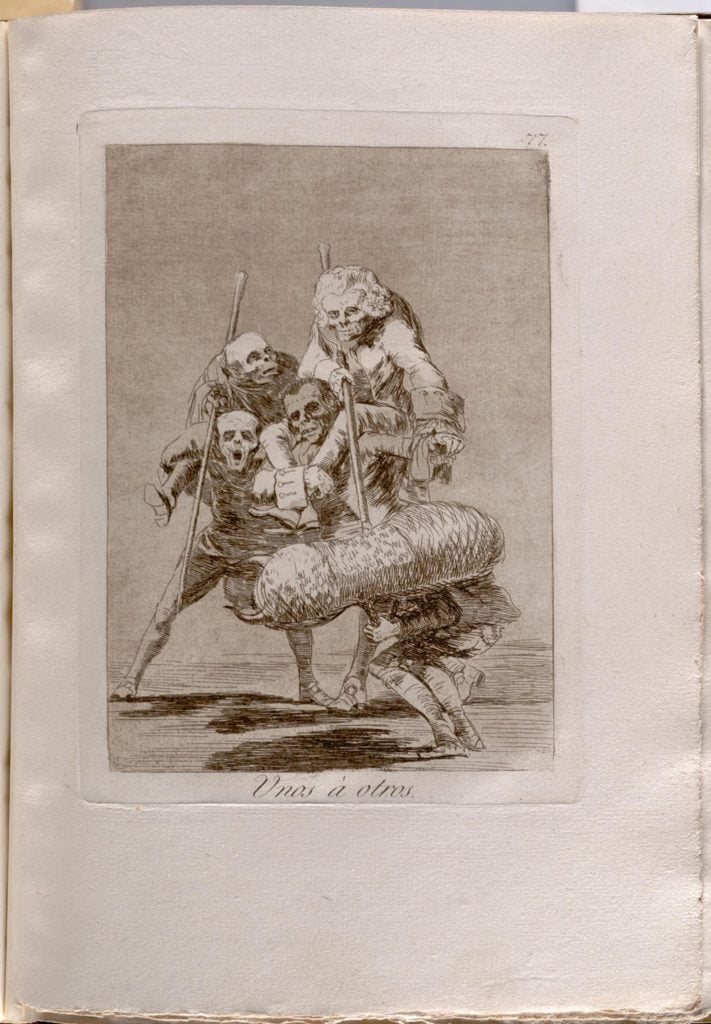

A Serious Upgrade for Goya’s ‘Los Caprichos’

Francisco de Goya Los Caprichos (The Caprices) (1796–1799)

Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Charles J. Rosenbloom

Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Charles J. Rosenbloom

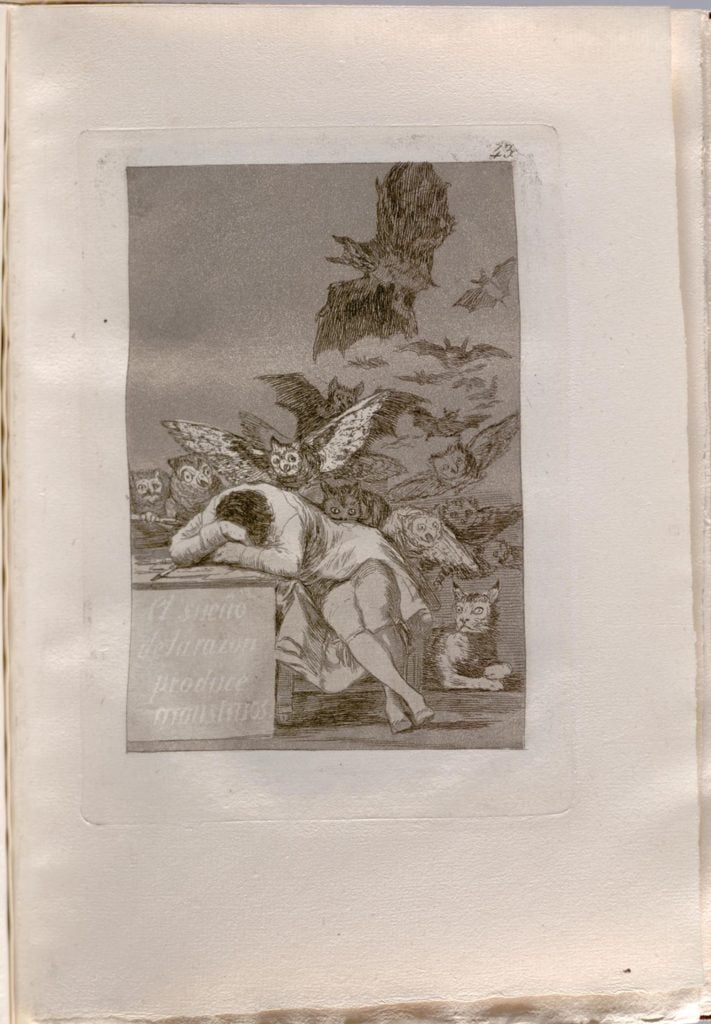

The Carnegie has always treasured its set of Goya’s satirical 80-print series “Los Caprichos.” But it wasn’t until very recently that curators learned, with the help of Old Master expert Armin Kunz at C.G. Boerner in New York, that its version is actually a first edition in its original binding. It also includes a number of proofs for Goya’s most famous image, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos).

“We knew it was Goya. We knew it was ‘Los Caprichos.’ But we did not understand the importance of that first edition or the presence of so many proofs,” Lippincott says. “This is a case where we had to add two zeroes to the value.”

Who ever said art history doesn’t pay?

Francisco de Goya, El sueño de la razon produce monstruos. (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.). Courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Charles J. Rosenbloom

“Visions of Order and Chaos: The Enlightened Eye” is on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh from March 3 to June 24.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE