|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Thursday, September 1, 2016

The Importance of Continuing Education for Digital Leaders

|

FEATURED ARTICLE

The Importance of Continuing Education for Digital Leaders

To keep up with changing technology, you have to be a perpetual student — no matter how experienced you are.

by Chris Curran

|

Welcome to strategy+business. Here’s what’s new.

The Importance of Continuing Education for Digital Leaders

Chris Curran is a principal with PwC US, based in the Dallas/Fort

Worth area. He is the chief technologist for the firm’s advisory

practice and he leads the firm’s ongoing Digital IQ research.

Whether you’re a newly minted MBA or an experienced leader, you’re always honing your skills and navigating change.

And technology is one discipline in which you really can’t afford to

stagnate. With digital transformation so central to strategy for most

companies, all executives — especially CEOs — must embrace a learning mind-set. Gone are the days you can delegate the job of keeping up with technology to the IT staff.

Chief information officers (CIOs), of course, should regularly brief the management team and the board on new developments, demoing exciting new technology, bringing in external speakers and vendors, and using other tactics that promote tech learning and engagement. But keeping up on technology trends is also the responsibility of every executive. And while that can be daunting given the vast tech landscape and seemingly limitless avenues for learning, it’s also incredibly exciting. So, if your job title doesn’t include the words information, technology, or digital, how do you stay current? And how do you ensure your organization isn’t falling behind? Consulting digitally literate kids, grandkids, or Millennial staff for help, as many chief executives tell us they do, won’t cut it. Here are three easy ways to begin boosting your digital acumen: 1. Get hands-on with new technology. Firsthand experience is a great way to better understand how your organization can apply technology to improve processes, better engage with customers, or create new lines of business. Personal exploration with emerging technologies not only adds to your knowledge base, it also puts you in the shoes of customers and employees. This forces you to think about the human experience, which is often ignored as companies think primarily about the strategic or technological implications of their digital projects. So go ahead: Play Pokémon Go with your kids. Download an AI assistant app. Take a VR walk-through of your kitchen remodeling project at the home improvement store. Or tinker with Internet of Things devices for your home like smart locks or automation hubs. What you learn in the process may surprise you. 2. Become a maker or a mentor. Take the hands-on approach one step further by mimicking makers, those intrepid do-it-yourselfers who play, experiment, and build tech-based projects. Attend a local Maker Faire, design a stapler, jar handle, or other household gadget on a 3D printer at your local library, join a makerspace in your community, and get inspired.

With digital transformation so central to strategy, all executives — especially CEOs — must embrace a learning mind-set.

Even if you’re not inclined to roll up your sleeves in the workshop,

you can still get involved — and get smarter in the process. I recently

had the opportunity to serve as a mentor

for my son’s high school robotics team. Now, in my role as PwC’s chief

technologist, I am immersed in technology innovation on a daily basis

and need only pop into our Emerging Technology Lab or visit one of our Experience Center

digital hubs to see the art of the possible. Yet even I learned a lot

from the experience of guiding a group of smart and enthusiastic teens

as they envisioned, prototyped, tested, and competed with their robots.

In particular, I came away with insight into effective innovation

practices that all enterprises would do well to emulate.

3. Get schooled online. Massive open online courses, or MOOCs, have grown in popularity. Learning platforms like Coursera, edX, and Udacity allow people to sample courses from leading universities. Indeed, the art of continuous learning itself may be the most sought-after skill for tomorrow’s workforce as well as the key to solving tomorrow’s problems. Explore the catalog of courses on any of these platforms to find the fields of study you’d like an introduction to, including design thinking, machine learning, and cybersecurity. In fact, at PwC we’re so bullish about the concept, we’ve recently rolled out a data analytics specialization on Coursera that’s available to everyone, not just our own people. Can’t commit to a MOOC? Become a regular downloader of tech-focused podcasts, such as those produced by 99% Invisible, A16Z, and Freakonomics Radio. And don’t discount the many TED talks, blogs, and newsletters that highlight tech developments, deals, and industry happenings. The trick is to take a disciplined approach, devoting as little as 15 minutes a day to as much as several hours a week. What about your company’s Digital IQ?Now that you’ve charted your own personal digital learning path, take a look at what your organization is doing. Has it been successful in raising its collective Digital IQ?Related Stories

What’s driving your company’s digital strategy? How are your leaders meeting its challenges? Which technologies are you betting on? How much have things changed over the last decade? Please click here to share your insights and reserve a free copy of the report as well as a one-year digital subscription to strategy+business magazine. |

Extraordinary Swimming Pools

From Turrell to Hockney, 8 Artists Who Designed Extraordinary Swimming Pools

Artsy Editorial

By Abigail Cain

Aug 29th, 2016 6:05 pm

Few

things evoke summer more than the swimming pool, its inviting blue

water offering a respite from sweltering heat. Pools have also served as

an unexpected medium for artists, from David Hockney to Katherine

Bernhardt. From filling pools with diet soda to painting them with

signature patterns, these eight artists have designed extraordinary—if

not always functional—swimming pools around the world.

James Turrell, Baker Pool, 2002-2008

Throughout his 50-year career, Turrell

has become famous for manipulating the perception of light and space in

mesmerizing installations. So it’s only fitting that, during a party to

celebrate the completion of Baker Pool in 2008, a

discombobulated guest unwittingly walked down the stairs and straight

into the water; Turrell himself pulled her out. The LED-lined pool,

commissioned for the basement of a barn on a Greenwich, Connecticut

estate, was the first such work the artist completed in the United

States. A previous Turrell-designed swimming pool, built for a French

cultural center, featured a central shaft that swimmers had to dive

under to catch a glimpse of one of the artist’s signature skyscapes.

David Hockney, Roosevelt Hotel, 1988

Known for his bright, airy paintings of Los Angeles swimming pools, Hockney

occasionally used the real thing as his canvas. The most accessible

example is located in Hollywood’s Roosevelt Hotel, where the artist

spent one morning in 1988 covering the pool bottom with a pattern of

swooping half-moon marks. Local officials attempted to paint over the

underwater mural later that year, citing a state safety law that

prohibited the decoration of swimming pools. Informed by a dealer that

the work would likely be valued at $1 million, they quickly changed

their minds and wrote a bill to exempt Hockney’s pool. The work remains

intact to this day.

Mike Bouchet, Flat Desert Diet Cola Pool, 2010

In the case of Bouchet’s Flat Desert Diet Cola Pool, it’s what’s inside that counts. In 2010, the artist filled an entire California swimming pool with Cola Lite,

his homemade, sweetener-free soda, then invited a group of art-world

denizens over to cavort in the syrupy liquid. Bouchet later repeated the

experiment on the roof of Chelsea’s Hotel Americano, hiring two female

bodybuilders to splash around while gallery-goers looked on. Both

installations are part of a series employing Bouchet’s carbonated

beverage as a medium; other works include watery brown canvases painted

with soda (the artist terms it “colachrome”).

Jorge Macchi, Piscina, 2009

In the mid-1990s, Argentinian artist Macchi

began a series of watercolors that merged several incongruous objects

into a single image. In one, a sheep stands on legs made from burnt

matchsticks; in another, the alphabetic tabs of an address book have

been transformed into a bench for a seated figure. The latter served as

the inspiration for Piscina, realized with the help of Brazilian

contemporary art museum Inhotim. One half of the work is crafted from

smooth white cement cut with strips of black granite, forming a

monumental sheet of lined paper. The pool’s focal point, however, is the

staircase of index tabs that descend into the clear blue water.

Samara Scott, Developer, 2016

Much of this young British artist’s work is liquid-based, although one would be ill-advised to take a dip in one of Scott’s

pools. For last year’s edition of Frieze, she gouged large holes in the

floor and filled them with an arresting hodgepodge of ingredients:

water, cooking oil, fabric softener, wax, even food. This month, she has

unveiled her largest project to date—a commission in London’s Battersea

Park, on view through September 25. Scott has transformed the park’s

two Pleasure Garden Fountains, adding multicolored dyes and swaths of

fabric that undulate beneath the surface and engage with the area’s

industrial past.

Katherine Bernhardt, Nautilus Hotel, 2015

Bernhardt’s pool design during last year’s Art Basel in Miami Beach

gave visitors to the Nautilus, a SIXTY Hotel, a chance to swim with

sharks—plus the socks, bananas, and Sharpies that also peppered her

pool-bottom mural. The project,

commissioned by Artsy for Nautilus, also featured Bernhardt-crafted

towels printed with toucans and French fries. Both works serve as prime

examples of the New York-based artist’s signature iconography: a mix of

tropical imagery and city-dweller staples, all rendered in bold, bright

color.

Berthold Lubetkin, Penguin Pool, 1934

This

one is literally for the birds. Lubetkin, a Georgia-born,

Paris-trained, Russian architect, designed this pool for the penguins at

the London Zoo in the 1930s. It was a prime example of pre-war Modern

architecture, earning Lubetkin international praise and establishing his

firm’s reputation as pioneers of the movement. The pool’s distinctive

looping, interlocking walkways were meant to highlight the penguins’

waddling gait. Years later, it was discovered that the sloping paths

were in fact giving the birds arthritis in their feet. The animals have

since been shifted to another habitat, although Lubetkin’s pool

remains—it is now classified as a water feature.

Ed Ruscha, Studio City

Photographed for the first (and only) issue of PUSH! magazine in 1991, this Ruscha-designed

swimming pool features one of the L.A. artist’s signature text-based

works. White tiles are arranged to create an underwater registration

form, confronting swimmers with blanks for their name, address, and

phone number. Ruscha, who made the work for his brother’s Studio City

home, said he considered distorting the words so that they would

straighten out when viewed through the water. In the end, however, he

decided against it—“that would have been an expensive experiment,” he

recalled.

—Abigail Cain

—Abigail Cain

These Photographers Quit Their Day Jobs to Travel the World

These Photographers Quit Their Day Jobs to Travel the World

Artsy Editorial

By Demie Kim

Aug 31st, 2016 1:42 am

Theron

Humphrey was shooting handbags and sweaters for a clothing company in

Idaho when he realized he needed a change. Overworked and uninspired, he

decided to quit and, after some soul-searching, stumbled on a wild

idea: to drive across America and meet and photograph a new person each

day for an entire year. So in August 2011, he set off in his pickup

truck with Maddie, his now Instagram-famous coonhound, and made his way

through all 50 states—even Hawaii—to capture and collect the unique

personal histories of 365 strangers.

Today, Humphrey has a loyal Instagram following of 1.2 million, a published book on his trusty companion, Maddie on Things, and a self-made career that he can take pride in. While it’s no doubt a risky move to leave a stable income, several others have made a similar leap of faith: They quit their jobs, packed their bags, and set off on adventures around the world, pursuing new walks of life that culminated in beautiful works of art. Below, we highlight eight photographers—from living legends, like Sebastião Salgado, to free-spirited nomad Foster Huntington—who’ve quit their day jobs for the thrill of an unknown future.

Today, Humphrey has a loyal Instagram following of 1.2 million, a published book on his trusty companion, Maddie on Things, and a self-made career that he can take pride in. While it’s no doubt a risky move to leave a stable income, several others have made a similar leap of faith: They quit their jobs, packed their bags, and set off on adventures around the world, pursuing new walks of life that culminated in beautiful works of art. Below, we highlight eight photographers—from living legends, like Sebastião Salgado, to free-spirited nomad Foster Huntington—who’ve quit their day jobs for the thrill of an unknown future.

In

1973, while sitting in a rowboat with his wife Lélia and working as an

economist in London, Salgado made the life-changing decision to quit his

job and pursue a newfound passion: photography. In the years prior,

Salgado had made frequent trips to countries in central and east Africa

to help initiate agricultural development projects for the World

Bank—and each time he brought along a Pentax Spotmatic II with a 50-mm

lens, a gift from his wife that had sparked an unanticipated obsession.

Now a world-renowned social documentary photographer, Salgado never

entirely parted ways with his background in economics. “When you go to a

country, you must know a little bit of the economy of this country, of

the social movements, of the conflicts, of the history of this

country—you must be part of it,” he has said.

This desire to understand, and thereby to honor, his subjects is

reflected in Salgado’s award-winning black-and-white documentary

series—including “Workers, “Migrations,” and most recently,

“Genesis”—which shed light on issues of poverty, oppression, and climate

change threatening displaced communities around the world.

Though Drake had never conceived of being a photographer growing up, she realized

in adulthood that “success is what you want it to be.” About a decade

ago, Drake left her New York office job at a multimedia company to

travel on a Fulbright scholarship to Ukraine, where she began to create

photo stories fueled by her interest in Russian, Islamic, and Chinese

cultures. “I was about 30 and I realized I didn’t want to work in an

office for the rest of my life, in New York’s bubble,” she explained.

“I wanted to learn about the world and cross into other communities.”

Wielding her camera, she made some 20 trips to countries in Central Asia

over the next 6 years, which culminated in two celebrated projects: Two Rivers

(2007-11), an in-depth look at the struggling economies, shifting

borders, and environmental calamity in the region between the Amu Darya

and Syr Darya rivers; and Wild Pigeon (2007-13), a collection of

photographs, drawings, and embroideries produced collaboratively with

Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group in western China, whose cultural freedom

is threatened by rapid modernization.

Foster Huntington

As

a concept designer at Ralph Lauren in New York, Huntington “got turned

off of working in fashion and designing things for rich dudes in

Connecticut” and realized

that he “shouldn’t be inside an office building working 70 hours a week

in my early twenties for some big-ass corporation.” So he did what many

stifled employees want to do, but never actually end up doing—he left.

In the summer of 2011, Huntington quit his job, moved into a camper, and

drove some 100,000 miles around the West, surfing and camping along the

way and documenting his journey.

Since 2014, Huntington has been living in a tree house in southern

Washington, along the Columbia River Gorge, which he designed and built

with a group of friends. (Its construction is documented in his book and

short film, both titled The Cinder Cone.) Now with an Instagram

following of over 1 million, Huntington hopes to inspire others to take

up his nomadic lifestyle—to see the world without relying on creature

comforts along the way.

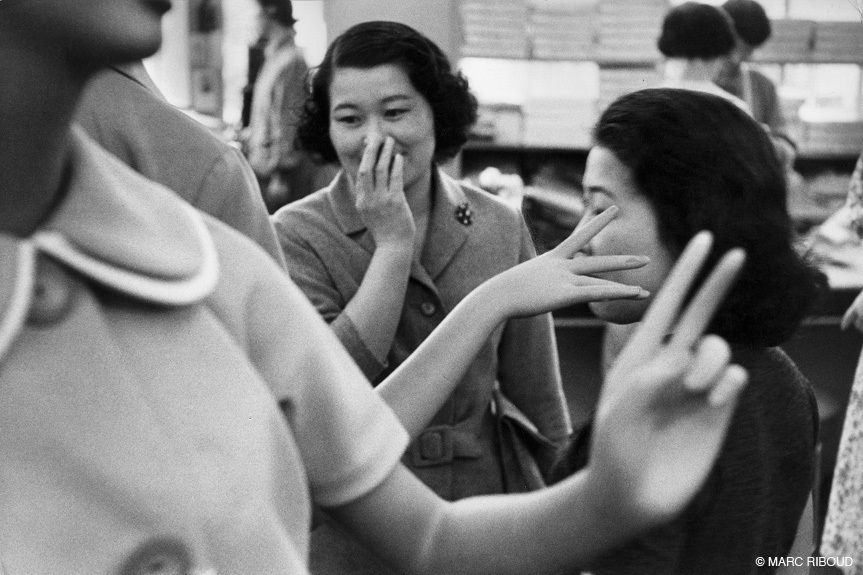

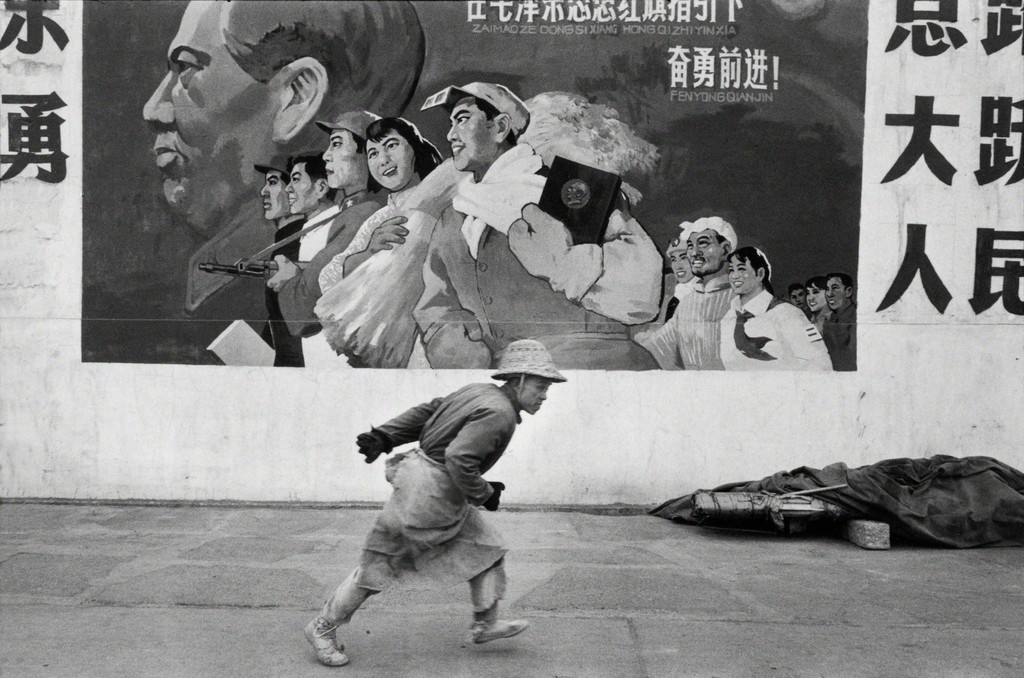

As a teenager—a self-described

“rebel” who later fought in the French Résistance—Riboud took his first

photographs at the Exposition Universelle of Paris in 1937 using the

Vest Pocket Kodak camera his father had gifted him for his 14th

birthday. But it wasn’t until the early 1950s, while on vacation and

photographing a festival in his hometown of Lyon, that he decided to

quit his job as an engineer at a factory, where he admitted he had

“spent a lot of time dreaming of other things and taking pictures on

weekends.” Starting off as a freelance photojournalist, he befriended Henri Cartier-Bresson and, in 1953, was accepted into Magnum—the same year his famous Eiffel Tower Painter photograph was published in LIFE. A fiercely independent spirit, and intimidated by the likes of Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa,

and David “Chim” Seymour, he promptly left France for two years—setting

off a career marked by international travel, most famously to the Near

and Far East. In these now-iconic photographs of civilians on the

streets of Mao-era China and the Vietnam War, Riboud captured quiet,

intimate moments amidst important historical events.

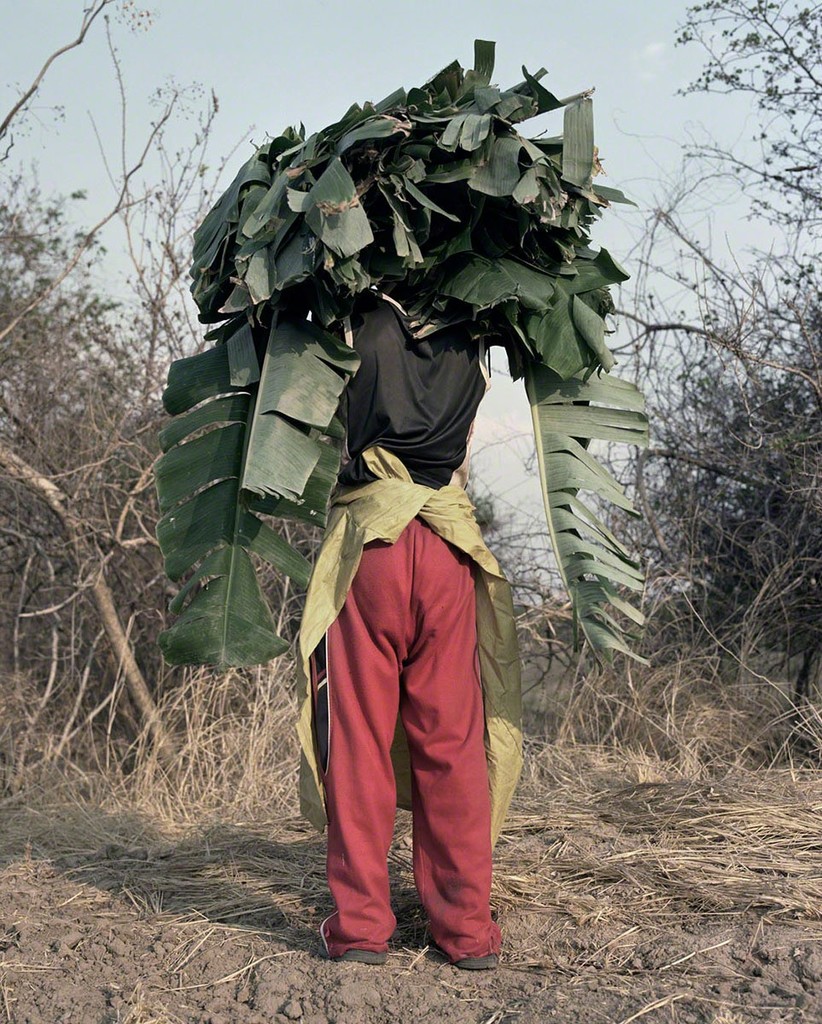

Boston-born

photographer Nickerson worked as a commercial fashion photographer for

the first 15 years of her career, shooting for Vanity Fair and Vogue, among other high-profile clients. Exhausted and disenchanted, she has recalled

thinking, “You’re wasting your life. If you want to do photography,

you’ve got to rethink this whole thing.” So when she accompanied her

friend on a visit to a farm in Zimbabwe in 1997, she became enamored by

the rural landscape and started to use photography as a means of

acquainting herself with local residents. A trip that was supposed to be

a few weeks long stretched into four years—and a new career. “I bought a

small flatbed truck and started to travel all around the country and

then went to South Africa, Malawi, and Mozambique. I took pictures of

everything,” she told TIME. Since then, she hasn’t stopped

traversing the globe, venturing back to Sub-Saharan Africa for portraits

of faceless farm laborers in her 2013 series, Terrain. Even in

recent forays back into fashion, the influence of these efforts is

clear, with the statuesque figures swathed in layers in a 2014 AnOther spread echoing the fashion and rural environs of Terrain. In the same year, Nickerson photographed four of the five Ebola Fighters covers for TIME—becoming the first woman to shoot the Person of the Year in the 87-year history of the magazine.

“It’s too late” is a mentality that sometimes impedes middle-agers from changing careers—but Canadian photographer Michael Levin

was never one to turn down a challenge. Though he had a keen eye since

childhood—“always looking at an interesting rock rather than a landmark”

on family trips—he found himself working as a restaurateur. Five years

later, Levin sold his business and picked up a camera at the age of 35.

He began by shooting stunningly spare black-and-white landscapes

inspired by Mark Rothko and Michael Kenna,

first around his home city, Vancouver, and then around the world—in

France and England, and later Iceland, South Korea, and Japan. He

attributes his marketing chops to his former career. “My job is to

promote my work as much as possible. That’s the reason that the work is

successful,” he once said. To aspiring photographers, he insists

that going full-time is “absolutely possible” if you recognize that

talent alone won’t cut it: “There are so many great photographs being

taken but you have to pursue ways to elevate your work and gain broader

exposure for it.”

In

1962, the now-legendary street photographer Meyerowitz was working as

an art director at an ad agency earning the equivalent of $29,000 per

week. After supervising a publicity shoot with photographer Robert Frank, the 24-year-old Meyerowitz walked around New York as if, he recalled in 2012,

he “was reading the text of the street in a way that I never had

before.” From there, Meyerowitz picked up his camera and began

hitchhiking around the American South and Mexico with his first wife,

his initial foray into the many trips he would take by road in the 1960s

and ’70s. Later, the photographer felt an impulse to “get away from my

familiar tactics and my familiar understanding of the American system,

the American way of life, to see what the rest of the world looked like

and what it would teach me about myself,” as he has explained.

In 1966, with his cherished Leica in hand, Meyerowitz embarked yet

again, this time on a year-long road trip across Europe. He began in

London and made his way across the continent—from France and Spain to

Greece and Italy, with several stops along the way—shooting “life along

the roadside whizzing by at 60 miles per hour.” These iconic

black-and-white photos led to his first show at MoMA in 1968, curated by

photography legend John Szarkowski.

Theron Humphrey

In

2011, North Carolina-born photographer Humphrey, having raised $16,000

on Kickstarter to pursue his wild idea, set off on his journey,

uploading images one by one to his website. En route, his project

evolved: He added an audio component, recording people’s voices, and

started an Instagram account. This was a drastic change from his life

just a few years earlier. On shooting product for a women’s retail

company, and not for himself, he once said,

“you start to lose your creative soul. There is a balance, and you need

to feed yourself, but if you’re only using your camera to shoot someone

else’s vision, it destroys you creatively.” Humphrey’s decision paid

off—he was named a Traveler of the Year by National Geographic in

2012. His advice to aspiring photographers is to “make work that isn’t

easy, that makes you feel uncomfortable, and make a lot of it….The slow

process of investing your time into a single idea is the greatest path.”

—Demie Kim

—Demie Kim

bbff

The Best Photos of the Day

Alphorn

players give a concert on August 28, 2016 in Nesselwang, southern

Germany, during a mass performance of 300 alphorn blowers. Karl-Josef

Hildenbrand / dpa / AFP

The Best Photos of the Day

(L-R)

German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Polish Foreign

Minister Witold Waszczykowski and French Foreign Minister Jean-Marc

Ayrault pose in front of the Goethe-Schiller monument in Weimar, eastern

Germany, where they met to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Weimar

Triangle on August 28, 2016. The Weimar Triangle is a loose grouping

that brings together Germany, France and Poland and was established in

the German city of Weimar in 1991. Jens-Ulrich Koch / AFP

The Best Photos of the Day

In

this photo taken on August 29, 2016, the newly-completed MahaNakhon

skyscraper is seen lit during a light show to celebrate its completion

as the tallest building in Thailand. MUNIR UZ ZAMAN / AFP

Art Demystified: What is the Role of Non-Profits in the Art World?

Art World

Art Demystified: What is the Role of Non-Profits in the Art World?

Can non-profits thrive in the profit-drive art world?

Between commercial galleries, museums, and auction houses

lies the arts non-profit. But in the profit-driven contemporary art

world, what role does the arts non-profit play?

Although every arts non-profit pursues different organizational goals, broadly speaking, non-profits fill the gaps left by the commercial and public sector to advocate issues such as art education, art activism, and promotion of unrepresented artists.01

Related: Art Demystified: What Is The Role of Art Advisors?

Many non-profits such as New York’s White Columns start as artist-run exhibition spaces that grow into fully-fledged arts organizations with dedicated programs. Others such as the Los Angeles-based non-profit Art + Practice are formed to address social issues and to provide education to foster children and kids from low-income families in neighborhoods where arts education may be inaccessible.

According to Jodi Waynberg, director of Artists Alliance,

a New York-based non-profit focused on community outreach and promoting

unrepresented artists, the absence of commercial pressures allows

non-profits be much more responsive to the needs of the arts community

as well as the community at large.

In a telephone interview with artnet News, Waynberg explained, “We’re able to dedicate resources to non-object based work, and projects that are more socially engaged or community engaged that don’t necessarily have a tangible result but are much more relationship oriented or idea oriented.”

Indeed Artists Alliance—which is primarily funded by governmental bodies—operates a gallery inside Essex Street Market on New York’s Lower East Side. Far from being a gimmick, running a gallery between vegetable stands and a butchers shop is a deliberate strategy to expose a section of the population to the arts that may not normally visit galleries or museums; at the same time it’s also a platform for emerging and unrepresented artists.

Waynberg explained, “One of the most important factors within arts

non-profits is that we really do have an obligation and a responsibility

to provide insight and light in dark corners across the art world and

for the communities in which we operate.”

Related: Art Demystified: What Determines an Artwork’s Value?

But is there still room for non-profits in an increasingly profit-driven art world? Waynberg certainly thinks so. “Because there’s such an increase in market-driven decision making…this is a really important moment for non-profits, and it’s a really significant opportunity,” she said. I know there is a lot of lamenting about the drive towards market-based decision making…but it really has created this incredible blank space for arts non-profits to take a greater position within the contemporary art world.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

Although every arts non-profit pursues different organizational goals, broadly speaking, non-profits fill the gaps left by the commercial and public sector to advocate issues such as art education, art activism, and promotion of unrepresented artists.01

Related: Art Demystified: What Is The Role of Art Advisors?

Many non-profits such as New York’s White Columns start as artist-run exhibition spaces that grow into fully-fledged arts organizations with dedicated programs. Others such as the Los Angeles-based non-profit Art + Practice are formed to address social issues and to provide education to foster children and kids from low-income families in neighborhoods where arts education may be inaccessible.

The

Chuchifritos Gallery + Project Space operated by Artists Alliance is a

popular venue on New York’s Lower East Side. Photo: Chuchifritos Gallery

+ Project Space via Facebook.

In a telephone interview with artnet News, Waynberg explained, “We’re able to dedicate resources to non-object based work, and projects that are more socially engaged or community engaged that don’t necessarily have a tangible result but are much more relationship oriented or idea oriented.”

Indeed Artists Alliance—which is primarily funded by governmental bodies—operates a gallery inside Essex Street Market on New York’s Lower East Side. Far from being a gimmick, running a gallery between vegetable stands and a butchers shop is a deliberate strategy to expose a section of the population to the arts that may not normally visit galleries or museums; at the same time it’s also a platform for emerging and unrepresented artists.

Los

Angeles-based non-profit Art + Practice was started by artist Mark

Bradford, activist Allan di Castro, and collector Eileen Harris. Photo:

Art + Practice via Facebook.

Related: Art Demystified: What Determines an Artwork’s Value?

But is there still room for non-profits in an increasingly profit-driven art world? Waynberg certainly thinks so. “Because there’s such an increase in market-driven decision making…this is a really important moment for non-profits, and it’s a really significant opportunity,” she said. I know there is a lot of lamenting about the drive towards market-based decision making…but it really has created this incredible blank space for arts non-profits to take a greater position within the contemporary art world.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

Article topics

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)