JUST WEIRD

The Most Scandalous Artworks of Marcel Duchamp

In addition to Marcel Duchamp’s famous readymades, during his life he created less known works that were provocative and caused a scandal among the public. Sexuality together with irony, were major themes in Duchamp’s later artworks. Beginning in the 1950s, he focused his attention on topics like the body, eroticism, and sexual symbolism. His pieces challenged the viewer, making them feel uncomfortable by looking at, and even touching them.

“Anything is art if an artist says it is.”

Marcel Duchamp

The Most Scandalous Artworks of Marcel Duchamp

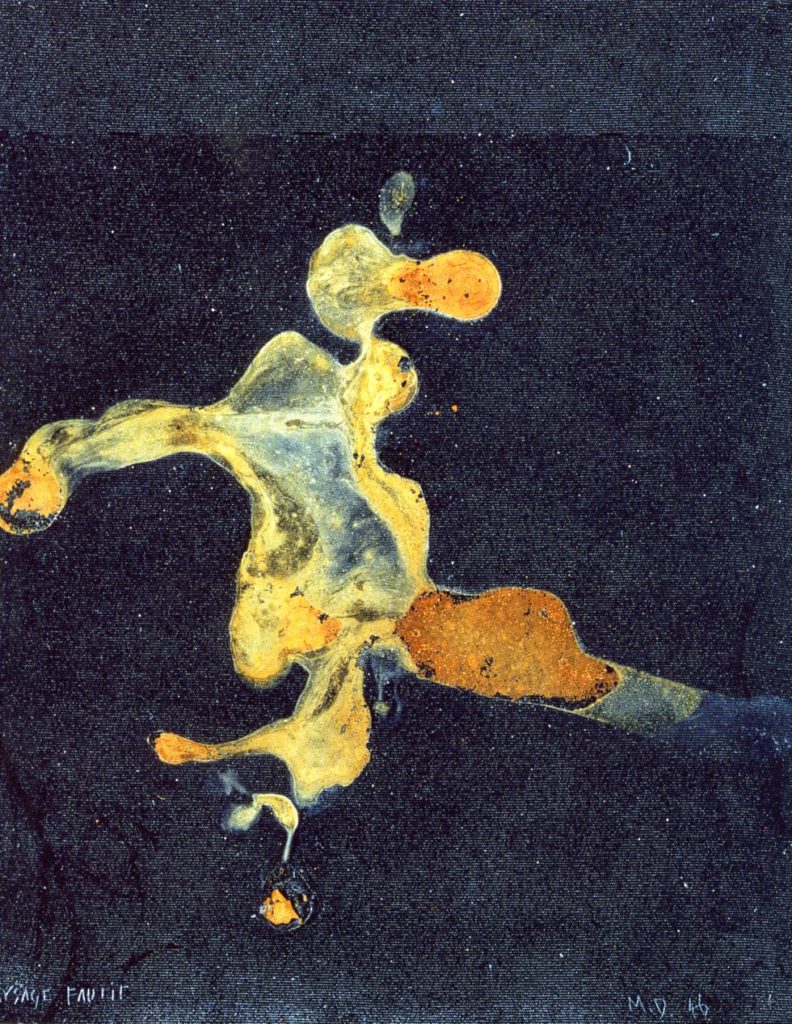

Faulty Landscape

Paysage fautif or Faulty landscape is one of the most original works of Marcel Duchamp. It was made in 1946 and dedicated to Maria Martins, a Brazilian sculptor and Duchamp’s lover whom he met in 1942. It represents a response to experimentation on the body and with the body in the art, a practice spread especially in the late fifties. This is considered such an original and provocative piece because of the material he used to create it – his own sperm. (Although it was not discovered until 1989 that’s Duchamp’s seminal liquid was used.) Even in 1946 this piece marked the beginning of a series of works, drawings, objects, and magazine covers which refer to eroticism and Freudian ideas.

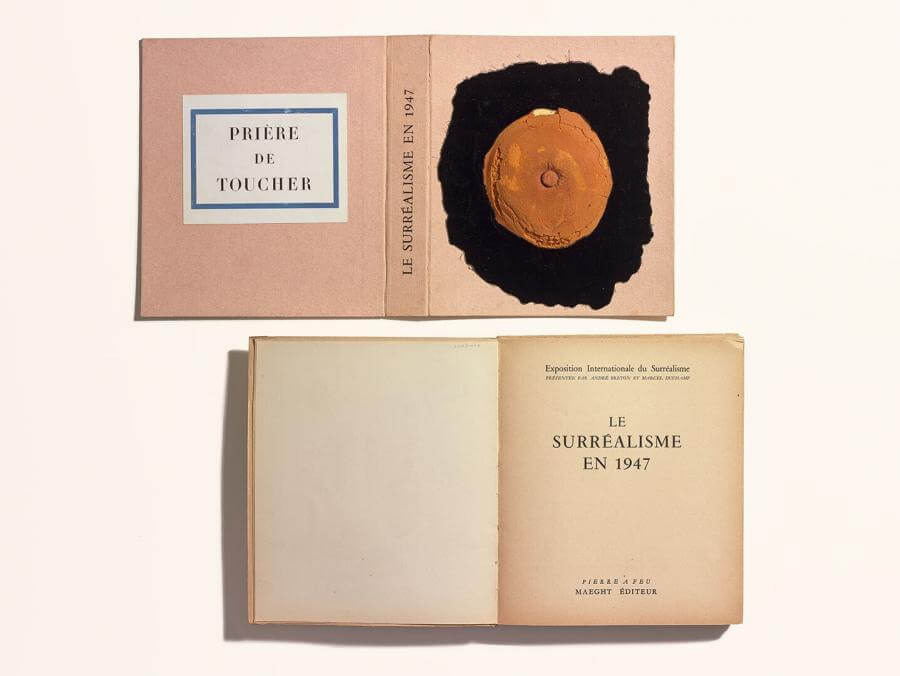

Please Touch

A year later, in 1947, Duchamp created a three-dimensional rubber breast on a black velvet background. He calls this piece Prière de toucher or Please touch. It was dedicated to Duchamp’s lover Maria Martins. This piece was designed to be the cover for a luxurious edition of the catalog called Le Surréalisme en 1947. The catalog was to accompany the exhibition Exposition Internationale du Surréalism. In contrast to most art, touching this work, is not only allowed, but encouraged.

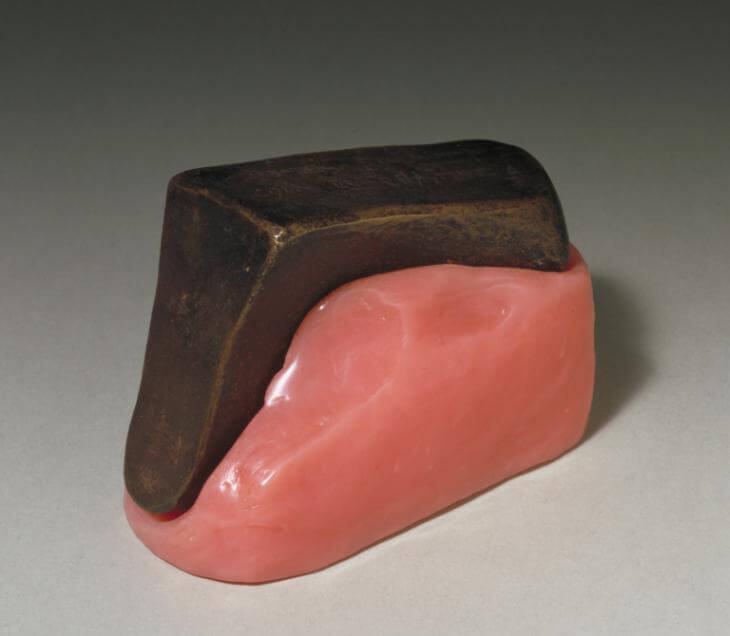

Four Small Erotic Objects

Duchamp continued to fragment the body, both male and female. This is the case with the bronze-plated plaster objects he created in 1950. In these works, the personal dimension emerges. Also the objects are all dedicated to women who had an important impact on his life. For example, Duchamp dedicated a small sculpture called Coin de chasteté or Wedge of Chastity as a gift to his second wife, Alexina Teeny Matisse (a daughter-in-law of Henry Matisse), on the occasion of their wedding in 1954.

This work is made up of two parts, a galvanized plaster piece stuck in red dental plastic. It is reminiscent of female genitalia, much like another Duchampian readymade Not a Shoe. (This is thought to be an early version of the Wedge of Chastity and it stands out from the group because of its name.) By bringing the word “shoe” into play, Duchamp immediately forces the viewer to interpret this otherwise ambiguous object as a shoe.

Object Dard, another one of Duchamp’s erotic pieces, is a phallic object made first in plaster and then in a bronze casting. The French title is a pun that alludes to an object d’art, or in other words, a work of art. While the word “dard” or “dart” suggests a masculine aggression, the phallic form could also refer to impotence. In this way, Duchamp mixes erotic and artistic meanings to curate a sense of ambiguity. On the contrary, Feuille de vigne femelle or Female Fig Leaf explicitly offers erotic meaning in the clear imprint taken directly from a female body (probably his wife’s).

Marcel Duchamp, Wedge of Chastity, 1954, Tate Modern, London, UK. Marcel Duchamp, Not a Shoe, 1950, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France. Marcel Duchamp, Dart Object, 1951, Tate Modern, London, UK. Marcel Duchamp, Female Fig Leaf, 1950-1961, Tate Modern, London, UK.

Étant Donnés

After Duchamp’s death, these bronze pieces were found to be connected with the last artwork of his career called Étant donnés or Given. Duchamp worked on this piece in secret from 1946 to 1966. It is now installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and was conceived to be mounted and exhibited after his death. Its full title is Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’eclairage or in English, Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas.

The viewer enters a separate room in the museum and is confronted with a massive old wooden door, framed in brick, in the center of a grey plaster wall. As one approaches it becomes apparent there are two eye-holes in the door. When one looks into the holes they are surprised to discover a panorama.

Behind the door lies a female body with legs spread holding in her left hand an illuminated gas lamp. She is in an unexpected landscape with waterfalls, a spectacular sight. This is visible only by looking through the peepholes, to create something truly extraordinary. The Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins obviously served as a model for the female figure. Duchamp used original materials such as pig hair for the female pubes to create a more realistic appearance of the whole trompe d’oeil.

It is difficult to understand the hidden meaning behind Étant Donnés. We can still see some connections with Sigmund Freud’s teachings about sexual impulses, oneiric states of mind, and Eros in general. Duchamp offers a physical and empirical vision. The spectator is obliged to enter with his own eyes to be able to observe the whole scene as a voyeur.

Since Duchamp did not leave any notes about his latest masterpiece, it remains enigmatic to this day. This three-dimensional realization or assemblage plays between inner and outer vision, between what is hidden and visible. For me, it is one of the most powerful, captivating, and breathtaking testaments to Duchamp’s unorthodox and revolutionary artistic skill.

If you enjoyed the scandalous artworks of Marcel Duchamp, you might want to read: