Ray Hahn

The Tragic End

of August J. Bulte

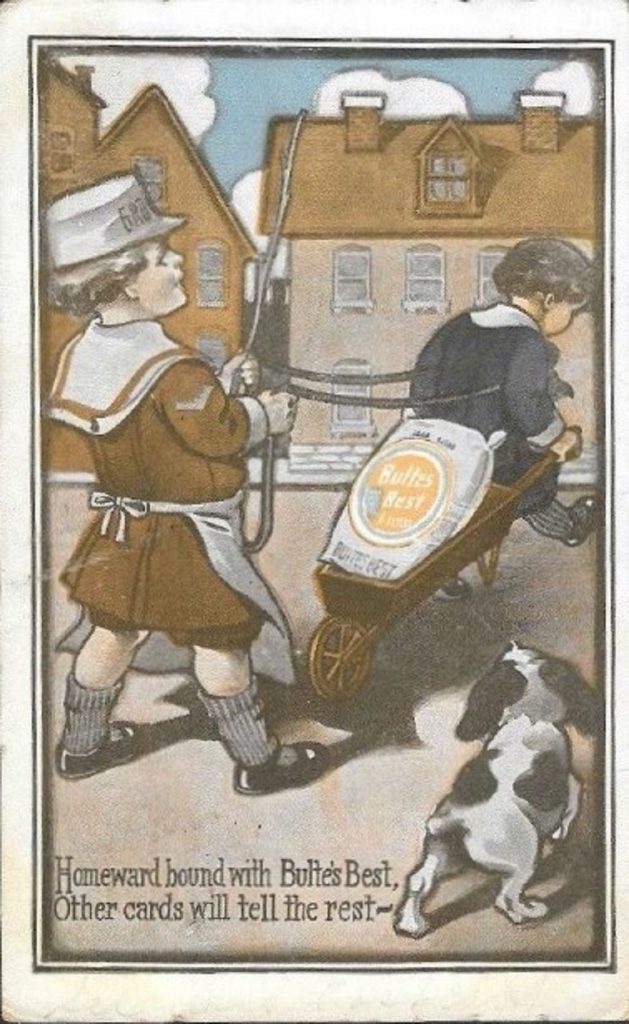

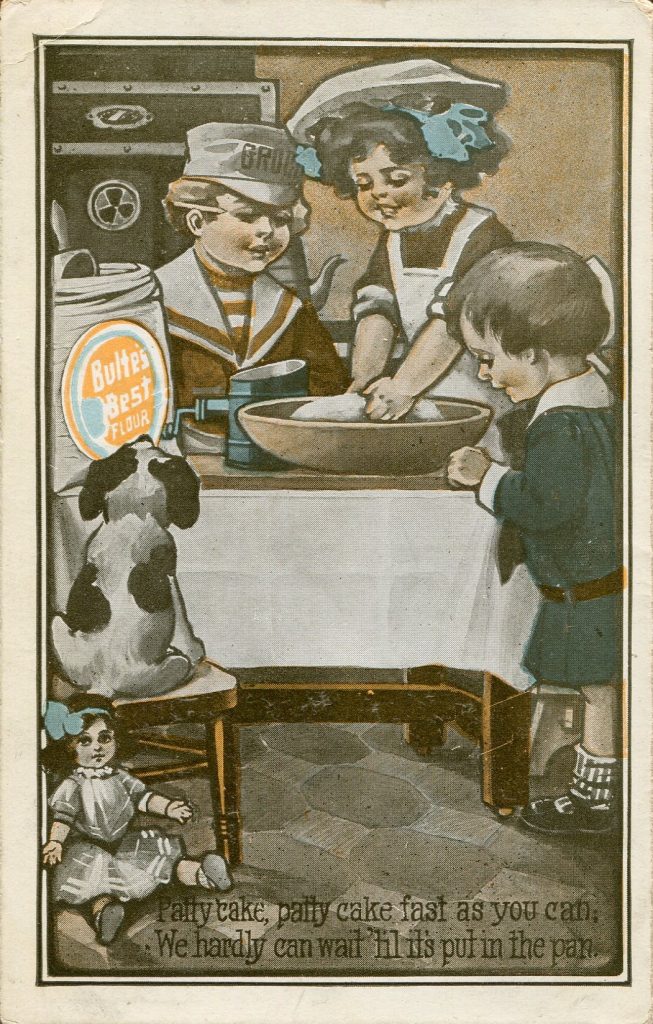

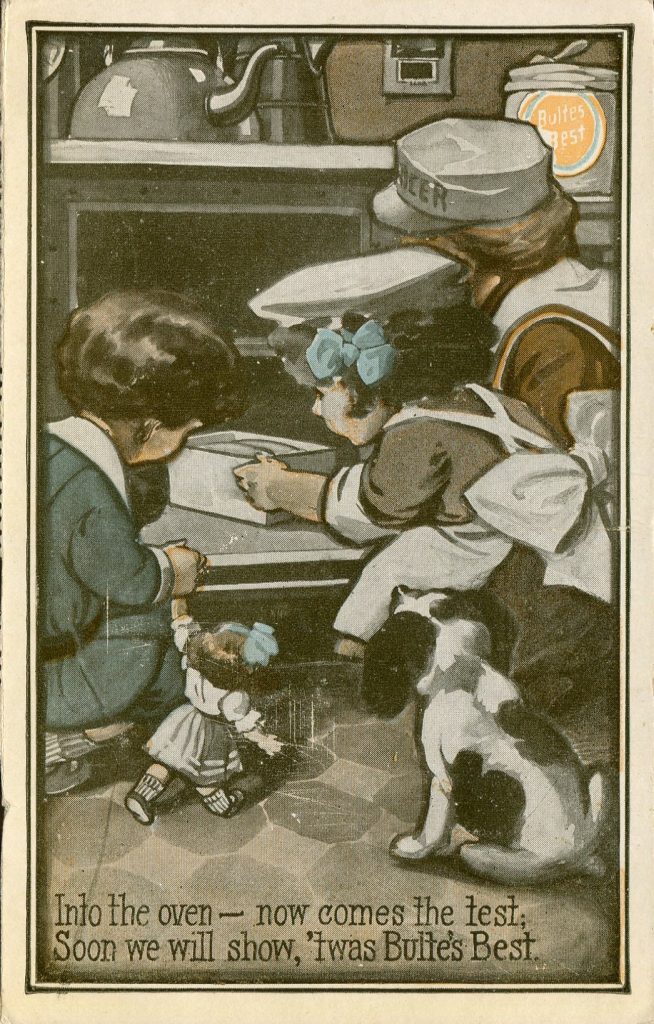

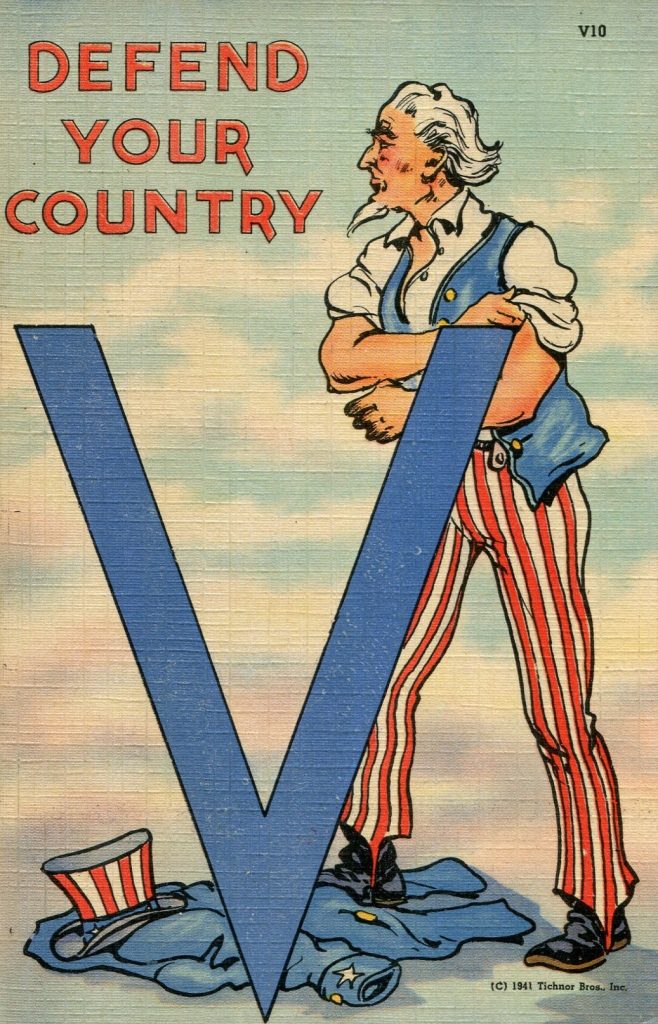

The average collector of advertising postcards will, when asked, give you a dozen good reasons for collecting, but the most common is that advertising cards symbolize elements that enhance the curiosity we have in social history. The postcards we examine here are wonderful examples, but they are so “sterile” that there is little to say about them that the images fail to portray.

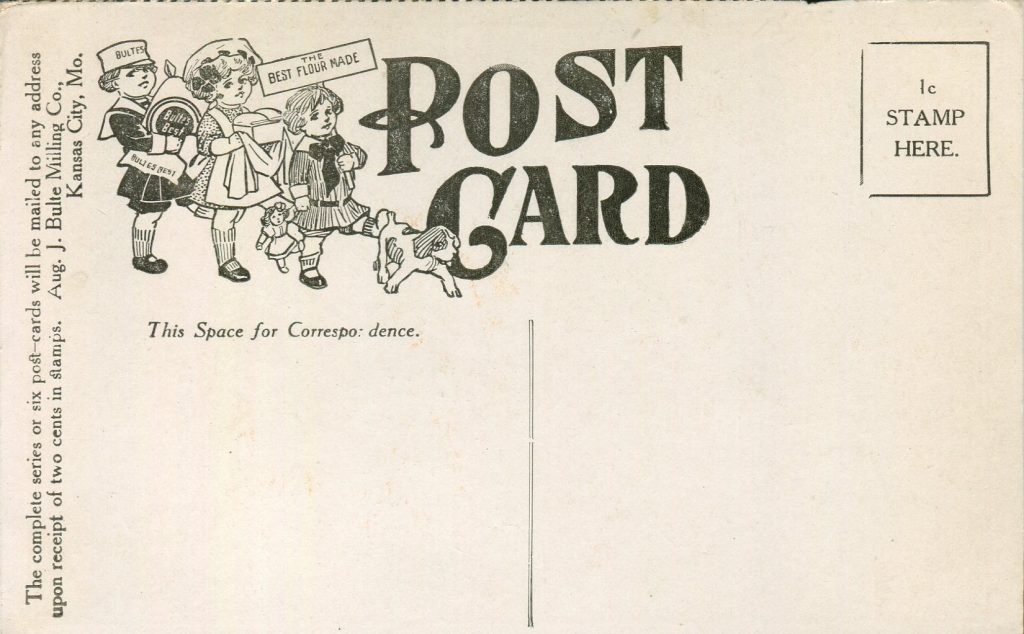

Each card has this wonderful post card apparatus that uses the same characters from the story-telling images to advertise the availability of the cards to anyone who sends two-cents in stamps to Aug. J. Bulte Milling Co., Kansas City, Mo.

The five cards on file at Postcard History are captioned:

Normally Postcard History would delay the presentation of such a story until the last card is found, but this one is too good to wait. And, it all has to do with the Bulte family and the horrible end that befell two of its members.

* * *

The oldest public documents signed by Casper H. (Heinrich). Bulte (spelled with an “o” instead of a “u”) are two deeds for land purchased from the United States government on October 1, 1845, and January 15, 1856, respectively. Casper, his wife Ann, and their three children: William, Catherine, and Frances (all born in Prussia) appear in the Seventh Census of the United States, 1850 as farmers.

Casper’s and Ann’s only son, William married between 1850 and 1854, and in the Eighth Census, 1860, he, his wife, and son August and his three baby-sisters were living with Casper and Ann in Franklin County, Missouri.

August J. Bulte (or Augustus, as he appears in other sources, i.e., the University of St. Louis academic records – was not among the students with an asterisk after his name. An asterisk was used to indicate students of high academic achievement) was born in St. Louis on May 27, 1862. Information about his youthful years is scarce but in a city directory from 1879 he is found as a clerk in a grocery store named Meyer and Bulte; likely co-owned by an uncle or great-uncle.

August disappeared from the public records until 1909 when he reappeared as the president of the Aug. J. Bulte Milling Company. This could well be within the period of the postcards mentioned above.

On October 16, 1916, A J’s wife Lena died at age 47. There is no way of knowing how his wife’s passing affected Mr. Bulte’s business affairs, but just three years later the A. J. Milling Company became Larabee Flour Mill Corporation.

August remarried in 1921 and assumed a job as vice-president and general manager of the Larabee Mill in Kansas City.

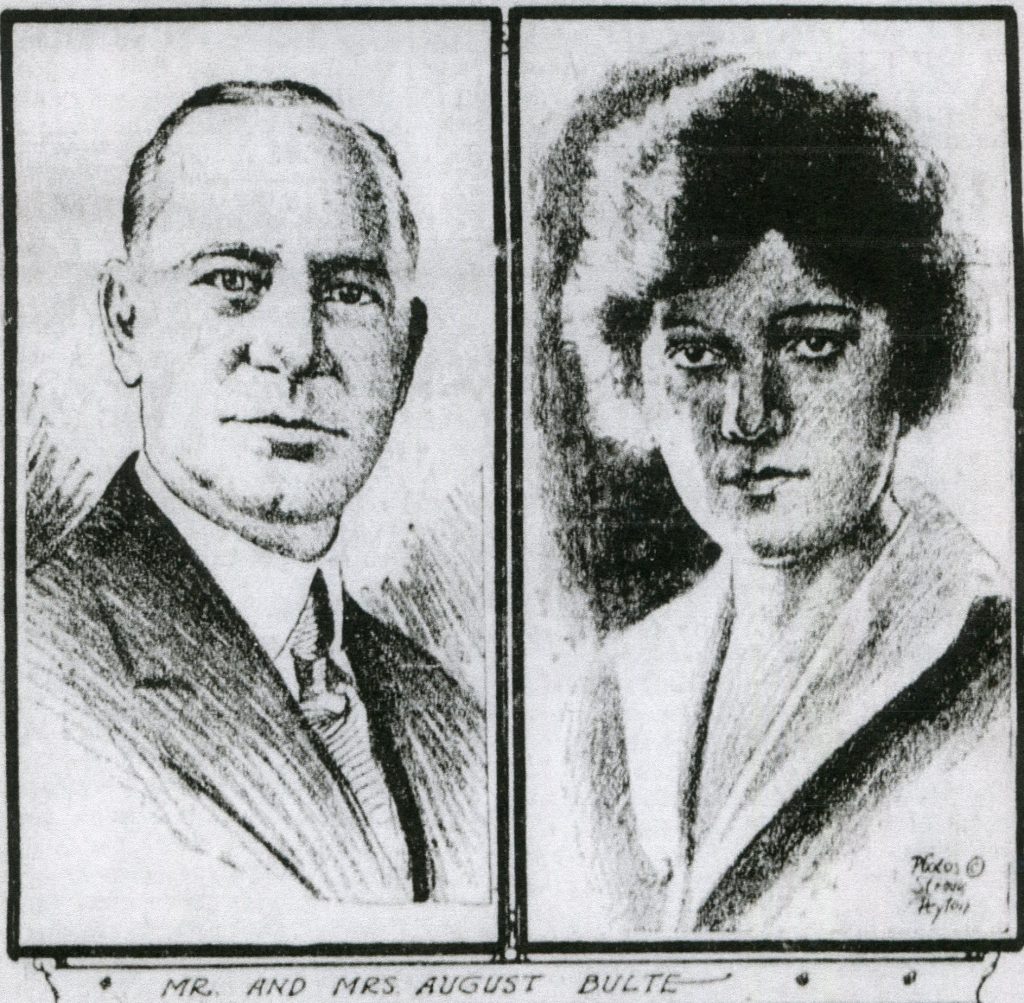

Then came March 7, 1922, when Mr. and Mrs. Bulte and their friends, Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence C. Smith, left Kansas City for a vacation in Florida and Cuba. (The following has been gleaned from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of March 25, 1922, and subsequent issues.)

One way-point destination for the vacationing couples was the Island of Bimini, one of the Bahamian Islands. The thrill of the trip to the island was as exciting as the destination. At some time after nine o’clock in the morning of March 22, 1922, the Bultes and Smiths arrived at the home hangar of Miss Miami, a seaplane (also dubbed a flying-boat) owned and piloted by one Robert Moore. Joining the others was a Mrs. Dixon of Memphis, Tennessee.

When the five passengers and their luggage were loaded the plane took off to the east into a fairly stiff breeze but as they crossed the shoreline and when out over the ocean all was well. The flight was uneventful until about twenty minutes west of their destination. Suddenly a piece of the propeller broke off and the plane immediately lost its momentum.

Mr. Moore attempted to land his flying boat near a fishing vessel or an island but could not manage his goal. The wind and the heavy sea-surges flipped the plane, and the passengers were forced to scramble for safety by clinging to bits of floating debris.

Eventually the five passengers perished, but Moore was rescued from the Atlantic fifty-five hours after the accident by the crew of the steamship (S. S.) William Greene. Details of the accident were wired to Bimini and forwarded to the Miami Herald.

The pilot’s account of the accident was published in newspapers from Boston to California. The papers in Kansas and Missouri were filled with dozens of hometown sidebars and memoirs of the Bultes and Smiths.

Newspaper sketches of Mr. and Mrs. Bulte

In the days and weeks that followed the story continued with the drama and machinations of the family’s lawsuits against nearly everyone they could find reasons to sue. The Bulte estate was estimated to include $5,000 in real estate and $50,000 in cash, business holding, and personal property. The estate (as best as can be determined from newspaper accounts) was settled in March 1927.