The Statue of Liberty Was Well Traveled Before She Reached Her Final Home

Parisians called her the “Lady of the Park,” and then said, “Au revoir.”

It was unpleasantly foggy and rainy on October 28, 1886, but New York City was celebrating. That was the day the Statue of Liberty was officially unveiled with much fanfare and ceremony. In the middle of some speech, the statue’s French designer Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi prematurely pulled the rope that released a large French flag draped in front of the statue’s face. When Lady Liberty’s copper visage was revealed, she officially became the tallest structure in the city—305 feet, 6 inches from pedestal base to torch tip. But that wasn’t the first time she had made an appearance. Before that, she had spent several years at home and abroad, and mostly in pieces.

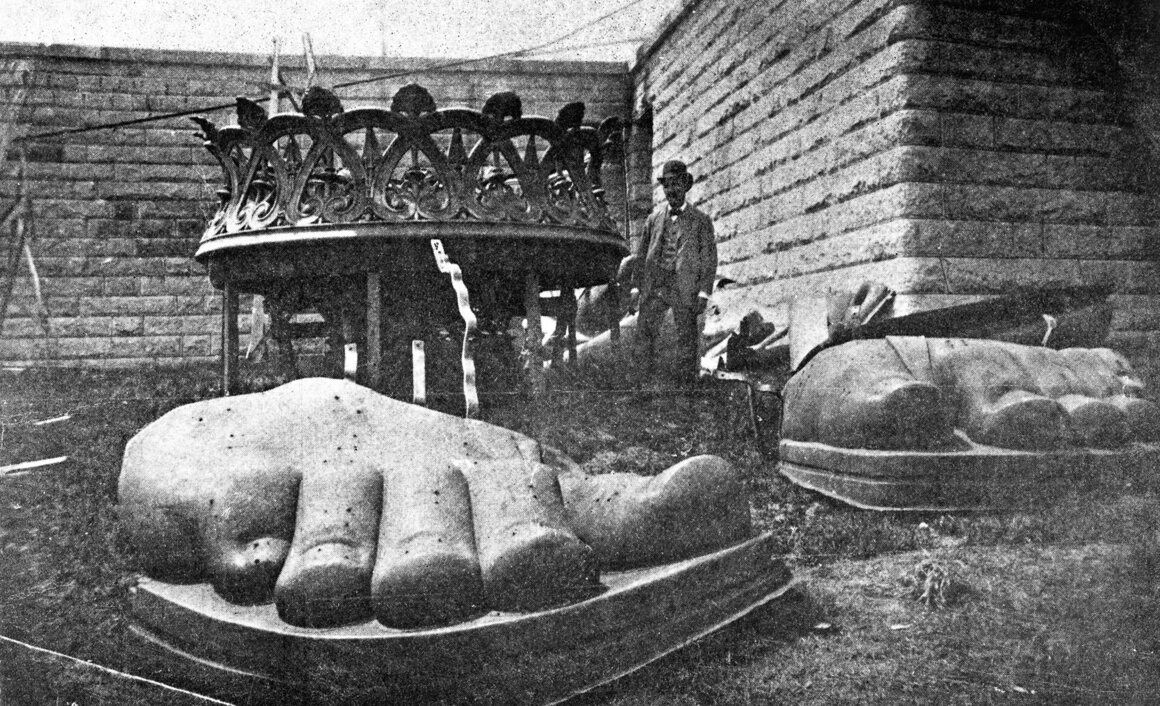

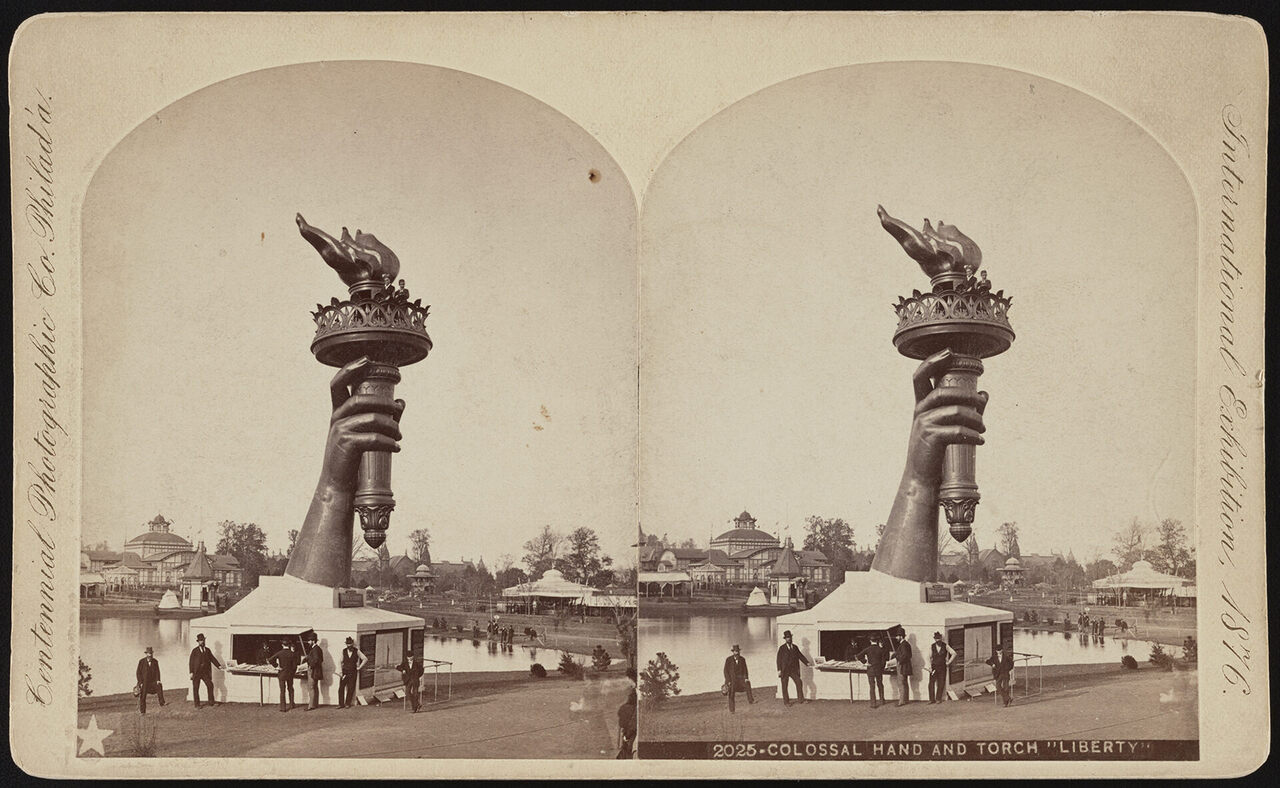

When Bartholdi had artisans begin constructing the sculpture in France in 1876, they started with her extended right arm and the lofty torch. He planned on that part of the statue first, deliberately, to raise attention and especially money, since at the time fundraising both in France (for the statue) and the United States (for the pedestal) was painfully slow. The arm was shown at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, and adventurous visitors helped raise funds by paying to climb a ladder in the statue’s forearm to the torch balcony. “It’s amazing (and even a little unsettling) to see the Statue’s disembodied head or arm today— and certainly no one in Bartholdi’s day had seen a work of art of this size,” says Carly Swaim, vice president of History Associates Inc., who worked on the recently opened Statue of Liberty Museum. The fire-bearing arm was then relocated to Madison Square Park in Manhattan, one of the most fashionable spots in the city, where it served, for blocks around, as an advertisement for the grandeur to come. Her arm stayed there for six years.

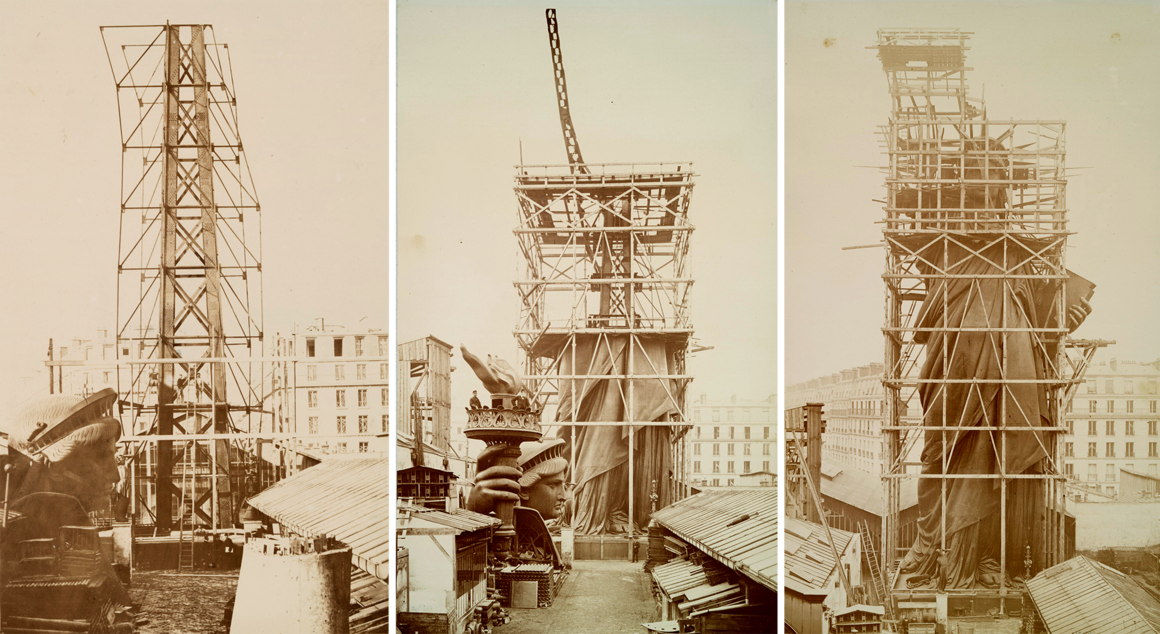

Lady Liberty’s head and shoulders were completed next, and they also had an independent, promotional life. While the right arm was in residence in Midtown Manhattan, her bust went on display at the Paris International Exposition in 1878. Once again visitors bought tickets to explore inside the statue—and they could also purchase entry to observe the bustle of activity at the construction workshops. “Bartholdi was immensely proud of his design,” says Swaim. “He hired professional photographers to document his team’s artistic and engineering prowess, but also to raise awareness and money for its construction … he hoped that these ‘action shots,’ along with many other fundraising efforts, would help the cause.”

Between 1881 and 1884, the entire statue—after the right arm was sent back across the Atlantic—was eventually assembled in a public park in Paris, to test the structure that would hold her up and together (engineered by Gustav Eiffel; you may have heard of him). The French people lovingly referred to her as the “Lady of the Park.”

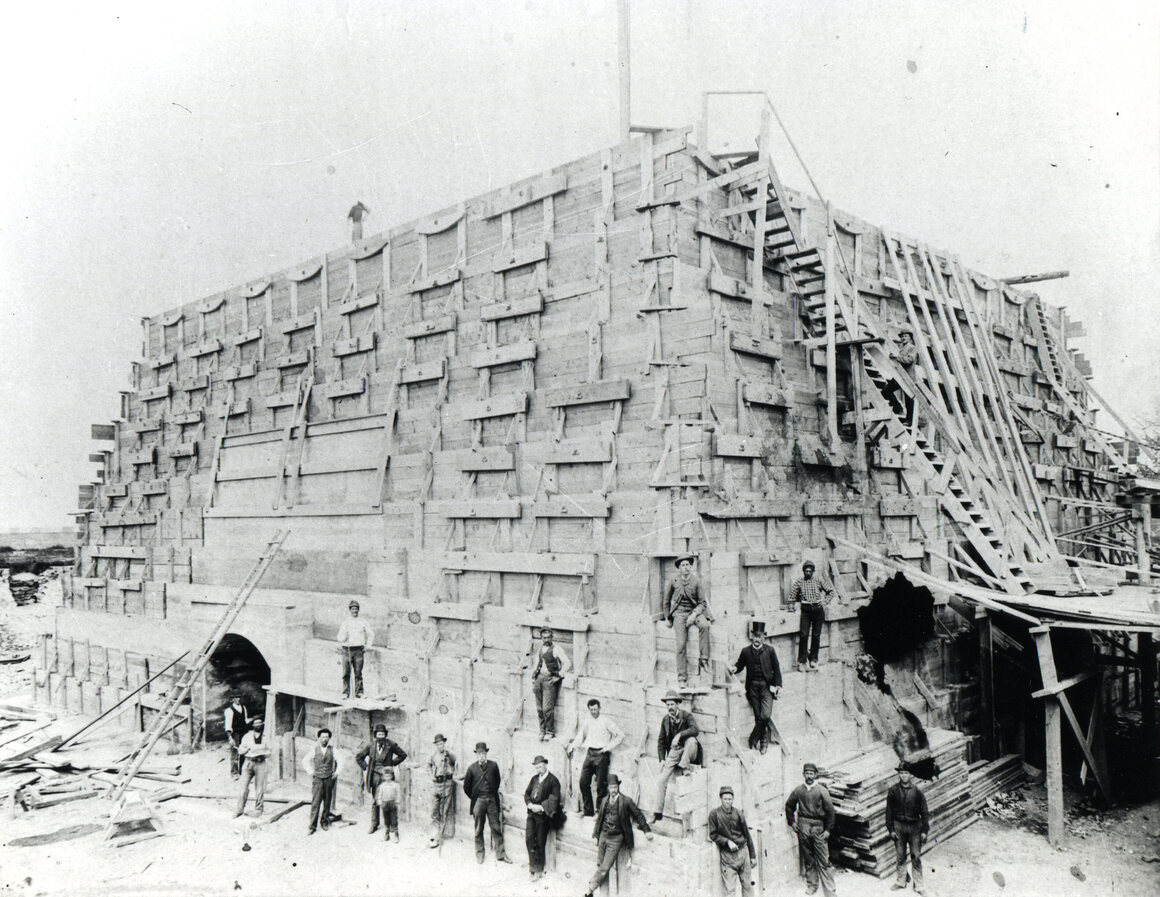

Her structural integrity established, she was dismantled into about 350 copper and iron pieces (ranging from 150 pounds to four tons) that were then packed in more than 200 wooden crates and loaded onto the French warship Isère. She made the crossing in 1885, and then had to wait, still in pieces, while her new home completed the pedestal on the to-be-renamed Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor. It took another year, but once it was done, construction crews worked quickly to assemble the enduring symbol of American values. It makes some degree of sense—after all, most of them were immigrants.

Her structural integrity established, she was dismantled into about 350 copper and iron pieces (ranging from 150 pounds to four tons) that were then packed in more than 200 wooden crates and loaded onto the French warship Isère. She made the crossing in 1885, and then had to wait, still in pieces, while her new home completed the pedestal on the to-be-renamed Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor. It took another year, but once it was done, construction crews worked quickly to assemble the enduring symbol of American values. It makes some degree of sense—after all, most of them were immigrants.