RE: O perigo é a minha profissão?

The Visionaries by Wolfram Eilenberger review – four women who changed the world

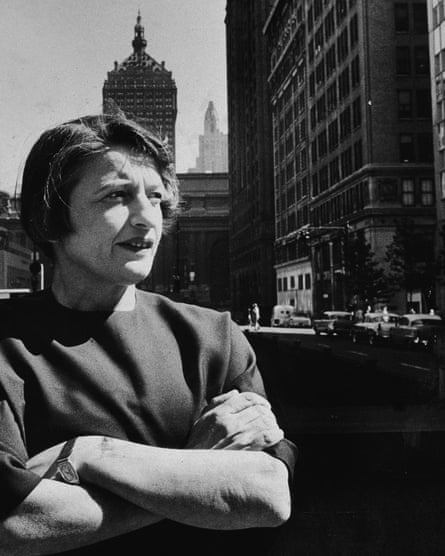

The complicated lives and questing minds of Ayn Rand, Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir and Simone Weil

In the summer of 1933, four women, all in their 20s, were busy contemplating the meaning of their own existence and the importance of others to it. The word existentialism had not yet been invented, but the quartet were intrigued by the idea of finding a new philosophy, using their own intelligence to change themselves and the world, while working out how the individual and the collective played into the malaise of modern times. Over the next decade, as Wolfram Eilenberger writes, they all crossed paths intellectually, sometimes agreeing, more often not, though it seems that they never actually met.

The eldest was an uncompromising and astute 28-year-old Russian who had got herself to Hollywood and changed her name from Alisa Rosenbaum to Ayn Rand. Through screenplays and fiction she set out to convey what she saw as the struggle for the autonomy of the soul, with “enlightened egoism” as her new vision for the world. Thus Spoke Zarathustra became “something like her house bible” and phrases such as “Nietzsche and I think …” peppered her philosophical notes.

Hannah Arendt, a former student of Martin Heidegger who was driven out of Germany at the age of 27 and suffering from a sense that she had lost all she held dear, did not share Rand’s total self-absorption. She believed the only way to confront the political turmoil of her times was to identify and tell the truth, and accept that no one can escape from history. Having been sensitised to her own Jewishness by the rise of Hitler, she planned to work for Jewish causes and get to grips with human rights and Zionism.

Simone de Beauvoir, linked to Jean-Paul Sartre in a pact of intellectual fidelity “as a single entity, placed together at the world’s centre” round which others circled, concentrated on herself against all others. She regarded humanity “as a backdrop to stimulate thought games”. Simone Weil, who, like Arendt, had fled Germany in 1933, was employed by a school near Lyon and spent her evenings tutoring factory workers in Saint-Étienne. The youngest of the four, and the most religious, Weil was sickly and self-denying. For her, the future had to lie in the subordination of the individual to the collective.

The Visionaries covers 10 years in these women’s lives as they faced alienation, fears for the future and disappointment, while searching for an intellectual framework by which to live. All four found writing an intense and on the whole enjoyable pursuit. Using letters, diaries, memoirs and published works, Eilenberger follows Rand as she revels in what he describes as something akin to a “narcissistic personality disorder” and embarks on The Fountainhead, which has, in Howard Roark, one of the more selfish and unpleasant characters in fiction. He traces Weil’s anguished identifying with the suffering of others, and Arendt’s search for “how to be both”, at once part of a loving couple and at the same time remaining true to your own identity.

For De Beauvoir, the 30s involved navigating the choppy waters of personal freedom and trying to be sympathetic towards all suffering human beings while paying attention mainly to herself. By the middle of the decade, her “coupledom” with Sartre was being threatened by a growing collection of shared young lovers – “all like snakes, mesmerised”, as one of them put it – to whom they allocated certain nights of the week.

The outbreak of civil war in Spain saw Weil determined to join the fighters and De Beauvoir determined not to, though she was outraged by the lack of intervention by France and Britain. Even if the rapidly approaching second world war was not a good time for philosophical missions of any hue, the four women kept writing, kept thinking, kept wondering about what constituted a “just war” and the nature of the violence it would entail. In New York, Rand, announcing that altruism was the enemy of freedom, set up a group of “intellectual aristocrats” and embarked on an “orgy of writing”. The Fountainhead, published in 1943, was a huge bestseller. De Beauvoir and Sartre went bicycling happily through Vichy France and ate Maryland chicken with André Malraux, even as Jews were being sent to internment camps, into one of which, Gurs, Arendt would soon be placed.

Three of the women survived the war. Weil, weakened by tuberculosis, starved herself to death in a sanatorium, leaving behind remarkable notebooks. Later, Albert Camus would say that she had been “the only great mind of our time”. Of them all, Arendt was probably the one who came closest to developing a new philosophical perspective. In his enjoyable book, Eilenberger manages to convey not only his characters’ complicated lives but the convoluted flow of their endlessly agitated minds. Rand may come across as intolerably egocentric, and De Beauvoir as little better, even if she was soon to become a founder of modern feminism – but the ceaseless intellectual questing of all four makes for fascinating reading.