|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

What Makes an Abstract Expressionist Painting Good?

What Makes an Abstract Expressionist Painting Good?

ARTSY EDITORIAL

BY ISAAC KAPLAN

DEC 21ST, 2016 5:02 PM

Photo by Bastian, via Flickr.

One of my responsibilities here at Artsy Editorial is to ponder the art-historical questions that are perhaps best answered either with a raised eyebrow or by saying, “because duh, that’s why.” Today’s entry in this series: What makes a work of Abstract Expressionist art good?

As in previous iterations (see: Why buy a painting when you can make your own?), the simplest of queries sometimes raises interesting and compelling ideas if one stares at it hard enough. In exploring subjective questions of quality and their relationship to the art-historical canon, one finds that a “good” AbEx work is one that is determined to be so by both the viewer and the critics and experts, as well as being the result of societal biases (more on that last part later).

Abstract Expressionism is perhaps one of the most recognized historical genres. Blame it on the impact of these typically large-scale, vibrant works, their permanent presence in the Art History 101 curriculum, or the skeptical cries of “My kid could do that!” The term originally rose to prominence in the mid-20th century to describe a group of artists working in New York following World War II. You know their names: Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline—the list goes on.

The painters were championed or chided (often both) by critics of the day such as Clement Greenberg, who had both unparalleled influence and art-historical clout, unlike critics of our current age. They had their own standards of AbEx quality—how flat a painting was, for example.

Though broadly interested in using abstraction as a way to convey individual emotions, the painters who worked in an AbEx mode actually spanned a wide range of techniques, styles, and intentions. In short, like all art-historical groupings, AbEx is both broad and somewhat limiting in how it brings together a diverse range of artists. Each artist had a signature style, from Pollock’s spontaneous, chaotic drip technique to Rothko’s atmospheric squares.

An understanding of this historical background and criticism are important, but really appreciating Abstract Expressionism is “not about reading a textbook,” said Gwen Chanzit, curator of modern art at the Denver Art Museum, who curated this year’s “Women of Abstract Expressionism” exhibition. Indeed, the quality of an Abstract Expressionist work can be gauged mainly by how it makes you feel.

This is, of course, true of much art. But AbEx works in particular—with their intense color, large scale, and, in Pollock’s case at least, frenzied application of paint—can elicit an emotional response from viewers that requires a physical, often prolonged, encounter with them. And the more you encounter these works, the more you’re able to judge them; this is true even for the pros. “You cannot be a curator in a vacuum. You have to be out into the world to see a lot of things. Then hopefully you recognize quality,” said Chanzit.

It’s key to recognize, though, that the canon of AbEx masters was also the product of societal biases, and that our subjective opinions are not always free from the influence of broader cultural realities. Most of the major AbEx figures are white men, despite there having been both artists of color and women working in the genre (see: Norman Lewis or Lee Krasner).

This is something Chanzit quickly learned as she curated her exhibition. “The truth is I did not set out to do a women’s show; I really set out to see who’d been left out of the canon of Abstract Expressionism,” she said. “When I began to see which people had been left out, I realized there was a whole gender missing.” She brought together over 50 works by 12 women painters associated with AbEx, including Krasner, Judith Godwin, Grace Hartigan, and Ethel Schwabacher.

But when one sees two abstract works side-by-side, regardless of the artist’s identity, how to determine which is better? How does one judge the quality of two similar works by Rothko, for instance? Part of the answer is time. “If you’re looking at a painting by Rothko, you need to give it time, so that you can almost lose yourself within that canvas,” said Chanzit. “You can’t walk by a Rothko and get very much out of it. But if you spend the time to immerse yourself within it, that’s when there’s a reward.”

There is, of course, also the historical significance of Rothko’s work. While his style may seem predictable now, at the time no one else was painting such rich, immersive fields of pure color that engulf one’s eyes.

Looking beyond the individual experience, I wondered how the market determines the quality of an AbEx painting—that is, how dollar and cent values are ascribed to paintings. Michael Macaulay, Senior Vice President and Head of Evening Sales Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s, is quick to note that the wide breadth of AbEx art means the label can lose some of its usefulness.

The result is that market evaluation is “artist-specific and then focused painting-by-painting,” he said. “We are of course bearing in mind its historical significance. We are evaluating a number of more quantifiable factors, like scale, palette, mode of execution, condition. And then there are a lot of softer factors to consider, like aesthetic appeal, which of course is very subjective.” Collectors have different tastes independent of the art-historical canon, too, perhaps valuing a Rothko over a Pollock, for whatever reason. And just as the general canon values women and AbEx artists of color less than their male counterparts, so too does the market.

Taking that earlier example of evaluating two Rothko works, Macaulay advises looking at the date, given that what year the artist created the work is “very critical” and can be connected to major moments in the artist’s career and art history generally. For the Rothko market, a golden year is 1954, “the year of his first solo exhibition at a major museum in the United States, held at the Art Institute of Chicago,” said Macaulay, adding that 1950 is another important year in the artist’s career, when he found his stride working in the “classic, stacked rectangular color form” he is known for.

No wonder, then, that the two most expensive Rothkos sold at Sotheby’s are No 1 (Royal Red and Blue) from 1954 and White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose), painted in 1950. Of course, both these works are stunning and rare. “I think at a certain level these works are all exceptional,” said Macaulay. “We can’t become too lazy in describing these masterworks as being a dime a dozen.” And saying one is “better” simply because it fetched more at auction is a limited metric, to say the least.

Macaulay also emphasizes how crucial it is to see these pieces in person. “You can’t replicate the experience of standing in front of a Mark Rothko, you can’t replicate the experience of standing in front of a Jackson Pollock,” he said. “The quality, the execution, the kind of intensity of the layers of paint, the quality of the drip is relatively discernible when you see these things first-hand. And it’s very important that you focus more on quality than anything else.”

And he cautions against leaning on the AbEx label as a crutch. Slapping it on an artist’s work obscures variations within their practice—see De Kooning’s flirtations with figures in works, for example (“there are so many chapters in his life,” said Macaulay). And at worst, such categorization asks us to evaluate an artist within a set of historical criteria rather than simply experiencing it. So when asking what makes a work of Abstract Expressionism good, read the wall label and the date, know a thing or two about the history, and check your own biases. But don’t forget to look.

—Isaac Kaplan

Censorship, “Sick Stuff,” and Rudy Giuliani’s Fight to Shut Down the Brooklyn Museum

Censorship, “Sick Stuff,” and Rudy Giuliani’s Fight to Shut Down the Brooklyn Museum

ARTSY EDITORIAL

BY ISAAC KAPLAN

DEC 23RD, 2016 11:41 PM

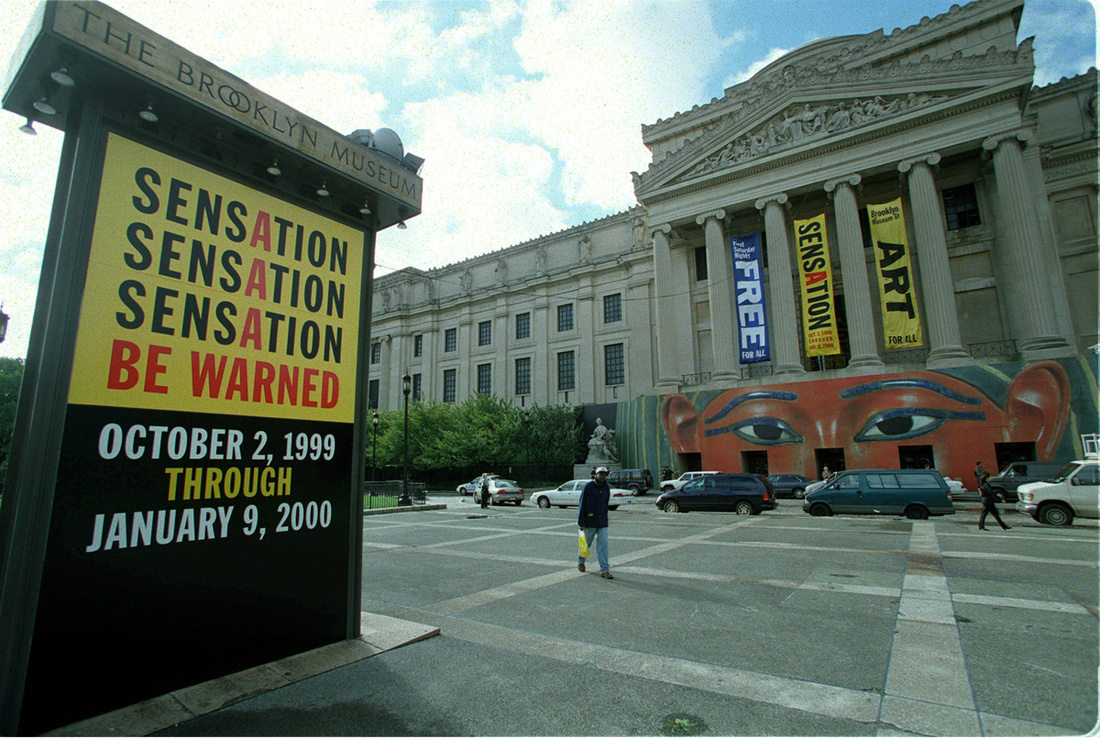

Photo by John Roca/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

It began, as many great New York City controversies often do, in the tabloids. On September 16th, 1999, the Daily News ran a little ditty (not even 600 words) headlined “B’Klyn Gallery of Horror. Gruesome Museum Show Stirs Controversy.” The exhibition in question, “Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection,” was described as a slasher flick—“R-rated” and brimming with “animals sliced in half, and graphic paintings and sculptures of corpses and sexually mutilated bodies.” Certainly not fit for the Brooklyn Museum, the paper implied, where it was due to open in a little under two weeks time. In defending the show, the museum’s director Arnold Lehman issued a warning to visitors that you would expect to find at a movie theater. And, ominously, Sunny Mindel, the press secretary of then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani, told the paper, “assuming the description of the exhibit is accurate, no money should be spent on it.”

The ensuing free-speech fight over “Sensation” would center around just that: whether the City of New York could cut off funding to the Brooklyn Museum over the controversial exhibition. The escalating battle threatened the literal existence of a major cultural institution in a way rarely seen since. On one side of the “Sensation” fight were Catholic groups and Giuliani, New York City’s pugilistic chief executive. On the other side of the battle was the Brooklyn Museum, which refused to call off the show, backed by legendary lawyer Floyd Abrams and the New York Civil Liberties Union. And in the middle of it all, a work of art: Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), which plays off classical iconography, depicting Virgin Mary as a black woman made of cow dung and set against a shimmering gold background replete with vaginas cut from pornographic magazines.

What happened over the fall and winter months of 1999 is a timely reminder that civil liberties are not won or lost in perpetuity but rather constantly being challenged and negotiated. And it is artists, irreverent by accident or by design, who often test the limits of the law and public opinion in ways that place them on the periphery of such conflicts.

The Stage is Set

Even before it arrived in Brooklyn, “Sensation” came to be defined, not so much by the works on view, but by what angry members of the public hurled at those works in protest. Featuring provocative Young British Artists (YBA) like Tracey Emin, Marcus Harvey, and Damien Hirst and drawn from the collection of the equally controversial ad-man Charles Saatchi, the exhibition began at the Royal Academy of Art in London in 1997. It was controversial overseas. But in England, the objections primarily focused on a portrait of the infamous Moors Murderer, Myra Hindley, who along with her partner Ian Brady, killed five children in the Manchester area during the mid 1960s. For his 1995 painting Myra, Harvey recreated an iconic image of Hindley on a large scale, using casts of children’s hands, in a work critics called an attempt to make money out of the murders.

Writing in The Independent, arts correspondent Tamsin Blanchard captured the ensuing scene as the show opened: “First red and blue Indian ink, then an egg, were smuggled through the security cordons and hurled on to the controversial painting of Myra Hindley. Before that we had shattered glass, megaphones, placards, images of media manipulation, tears, confusion and bewilderment. And that was just in the courtyard.” Though police from London’s vice squad patrolled the exhibition, they found nothing illegal, a determination that Blanchard, attuned to the show’s desire to push the limits, called “a damning piece of art criticism.” The dawn of the contemporary blockbuster, “Sensation” became the highest attended contemporary art exhibit in Britain of the previous 50 years. And many visitors felt the protests and reaction were out of proportion to the work and its message—one that powerfully juxtaposed childish innocence with the face of a killer. A survey showed 90% who actually saw “Sensation” believed the RA had the authority to mount the exhibit.

In the leadup to the exhibition’s U.S. opening on October 2nd, 1999, the Brooklyn Museum wasn’t looking to soothe public opinion, running ads that said “be warned” in red capital letters. But court documents eventually revealed that Lehman informed the mayor about the exhibition over two months before it opened. Lehman received no objections at the time, though the mayor later charged the full scope of the exhibit wasn’t made clear. The museum may have briefed the mayor about “Sensation” no matter who held the office. After all, the city provided significant funding and leased the building to the institution. But Giuliani perhaps warranted particular care since, after his election in 1993 on a platform of law and order and quality of life, the mayor was no stranger to impinging on the first amendment, to the displeasure of artists.

In the 1990s, such free speech fights were the “heart and soul” of the ACLU, recalls Norman Siegel, the former executive director of the civil liberties union’s New York branch. “I was shocked when I heard Giuliani was going to run for mayor because my recollection of Rudy Giuliani was the he was not a people person,” Siegel told me of the man who was also his classmate at NYU law school. Before leaving the NYCLU in 2001, Siegel kept a scorecard of first amendment cases brought during the subsequent mayoralties of Ed Koch, David Dinkins, and Giuliani. As Siegel remembers it, the NYCLU brought and won the most free speech cases under Giuliani. An American Bar Association article described how “law professors in New York (and elsewhere) have been thanking Mayor Rudolph Giuliani for ‘constantly generating classroom hypotheticals’ for teaching the First Amendment.” But still, controversial works of culture, even those dealing with the Catholic faith to which Giuliani subscribed, had passed without much in the way of real scorn from the mayor. “Sensation” might have been among them.

But then, on September 22nd, Rudy Giuliani held a press conference.

Photo By Jonathan Elderfield/Getty Images

The Fight

Giuliani had only seen a catalogue for “Sensation” when Mary Gay Taylor, a CBS reporter, asked him a question about the show at the prompting of the mayor’s aides. “Well, it offends me,” Giuliani replied, immediately singling out Ofili’s image of the Virgin Mary. “The idea of, in the name of art, having a city-subsidized building have so-called works of art in which people are throwing elephant dung at a picture of the Virgin Mary is sick. If somebody wants to do that privately and pay for that privately, well that’s what the First Amendment is all about,” he said, adding, “The city shouldn't have to pay for sick stuff.” Those two words—“sick stuff”—came to define the criticism of the show mounted by some Catholics who felt that using dung in a work with a religious icon like the Virgin Mary was offensive and sacrilegious. And certainly something that shouldn’t get public funding.

Even as Lehman and others defended the show, the mayor ramped up his rhetoric against the museum and threatened the $7 million it received from the city in operating expenses. This represented a mortally significant chunk of the museum’s $23 million budget. Also at stake were $20 million in capital improvement grants. Upping the ante, Michael D. Hess, the city’s corporate counsel, sent a letter to the museum saying that it was violating the terms of its lease and that the government could step in and replace the board of trustees with people who “have better judgment as to what is appropriate for this type of museum.” The potential of eviction loomed. Some wondered why Giuliani was taking such a strong stance. Did it have something to do with shoring up support among New York State Catholics in advance of a potential Senate run against Hillary Rodham Clinton? Did he really just hate the work? And if he did, was it because of the dung or because the Virgin Mary was black?

Then lawsuits began to fly as talks between the mayor and the museum faltered. On September 28, the museum filed a preemptive suit asking for a judge to prevent the city from withholding public funds meant to be paid to the institution each month. The city went ahead and held back an October 1st payment of $497,554 anyway. Two days later, lawyers for the city filed a suit of their own arguing for the immediate ejectment of the museum on the grounds it violated its lease, its funding contract, and its enabling legislation. “What’s he going to do, take all the artwork and throw it out on the street?” Siegel remembers thinking at the time. By way of legal justification, the city devised numerous, sometimes seemingly contradictory arguments, challenging everything from the private funding of the exhibition by Saatchi to the museum’s policy requiring those under 17 to see “Sensation” with an adult. “First we are told how vile and degenerate the exhibition is, and now we are being expected to open it up to children?” an incredulous-seeming Lehman told the Times.

Though at moments it approached a sad farce, at the core of the debate was the serious question of if public funding could be withdrawn from a museum because of the works displayed inside were seen as offensive. Did that violate the first amendment’s guarantee to free speech? Groups like NYCLU filed briefs in support of the museum saying yes, charging the government with censorship and writing that “the First Amendment also bars Mayor Giuliani from using City funding to dictate the content of a curated art exhibition.” They had Supreme Court jurisprudence on their side. “There is no doubt now, and there hasn’t been doubt for some time, that there is broad, even sweeping, protection for the arts as a result of the first amendment,” Floyd Abrams, the museum’s attorney at the time, told Artsy. Though obscenity laws have been found constitutional—a legal standard set by another art related court case in which Karen Finley battled against the NEA—the justices also ruled that while nothing compels the government to fund art, the state cannot withdraw funding due to the contents of a work of art.

As the case proceeded through the courtroom, outside, a battle in the larger court of public opinion insued. “I felt we needed to do something more than just be in the court. The instinct here was that this is something you should make larger than life,” Siegel said. “And it was also important, for us, to urge the arts community not to be timid, intimidated, or chilled by this misdirected efforts by the government. Instead it should be bold, creative, visible, and vocal in opposing censorship or intimidation.” The reminder was perhaps needed, with some critiquing the relatively tepid statement issued by the Met and the MoMA. Then-Met director Philippe de Montebello published an op-ed, critiquing the mayor’s position but also the contents of the work as lacking substance. “Even as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he is not to be the judge of what the public deems ‘good’ or ‘bad’ any more than Mayor Giuliani,” shot back a reader’s letter to the Times.

As the debate unfolded, a rally in support of the museum was held nearby and attended by thousands, including celebrities and artists from Susan Sarandon to Norman Mailer. “I didn’t want to go home that night,” said Siegel, who MC-ed the speakers. “You have these moments that you know are pure. Closing my eyes now, I remember where I was standing, just seeing a sea of people, racial diversity, different ages. And people really coming to understand the importance of the first amendment.” Another, though reportedly smaller rally, was held nearby on the same day by the the Catholic League’s president Bill Donohue, an early critic of the show for both “its anti-Catholic nature” and “the fact I’m paying for it,” he told me. In response to the museum’s decision to erect mock health warnings that “the contents of this exhibition may cause shock, vomiting, confusion, panic,” Donohue handed out 500 vomit bags during the demonstration. “I said yes, we would agree with you on that. And we wanted to make sure no one slipped on the barf,” he told me. “We passed out the vomit bags to make a point.” (Not above working together, Donohue and Siegel held a joint press conference during the debate to jointly condemn bigotry.)

Once again, people made their displeasure known. Scott LoBaido, today a Trump supporting artist, hurled horse manure at the museum over the work. (It was not the last time he would tussle with the institution over works perceived as anti-Catholic.) But a poll conducted by the New York Daily News showed that 60 percent of all New Yorkers and 48 percent of Catholics disagreed with Giuliani's position. With each side’s case made to the public, all eyes turned back to the courtroom.

The Aftermath

On November 1, Federal Judge Nina Gershon delivered a 40 page opinion. In it, she ruled that the Brooklyn Museum had a high likelihood of prevailing if the case continued to trial. Gershon went further, issuing an injunction forbidding the city from withholding any more funding, evicting the museum, or replacing the board of trustees. The first amendment, she ruled, barred the government from using funding as means to coerce speech. It was a sweeping victory for the Brooklyn Museum. “The Judge is totally out of control,” Giuliani said in response to the verdict. But in March, bluster gave way to resolution. The parties settled out of court, with both sides paying their own legal fees and agreeing that the museum would be safe from future acts of retaliation from the city.

Today, over 15 years later, the impact of the decision can still be felt. “I think the notoriety of the Brooklyn Museum case has served as a significant protector for the arts thereafter,” Abrams said. He pointed to an exhibition of classified NSA materials shown as part of Laura Poitras’ Whitney exhibition in February and March of 2016. “No one even talked about the possibility of prosecution of the Whitney,” he said. “It’s like the Sherlock Holmes story about the dog who didn’t bark. The fact that there was not even a public discussion about whether [the Whitney] was at risk or should be prosecuted is telling about the degree to which the first amendment has come to play a continuing role in the protection of the arts.” Granted, who knows what might have happened if someone other than Barack Obama was living in the White House.

Even when artists win these lawsuits, they can have a chilling effect on the work people make or what institutions choose to show. Such self-censorship is “one of my goals,” said Donohue, who doesn’t want the government censoring exhibition. Donohue said that he will continue to protest those he finds offensive in hopes artists voluntarily avoid such subjects in the future. Still, a Chris Ofili retrospective at the New Museum in 2014 proved not only that museums were not afraid, but also reminded viewers that his output amounted to more than one work, in one exhibition, over a decade ago. “We thought that it was also important to show the impressive range of his work, from the work he’s more well known for—the extremely intricate and ornate paintings that he made in the ’90s—to the subtle blue paintings and vibrant and expressive recent paintings that he’s been [making] since his move to Trinidad in 2005,” Margot Norton, one of the New Museum curators told Artsy in 2014.

“Sensation” continues to provoke debate. It was evidence that spectacle could get visitors into the gallery. And the personal benefit Saatchi received from a museum show of his collection—which was also partially sponsored by Christie’s—continues to be controversial as the art world continually privatizes. (Many remain critical of corporate sponsorship of public museums.) Even though the Brooklyn Museum case was a resounding victory for the museum, the culture wars of the 1970s and 1980s ended with an obscenity law firmly intact and a National Endowment for the Arts that has seen funding gutted and relevance diminished. And even with legal protections, those most vulnerable to government interference are the artists and institutions which lack the resources or public pull to defend themselves in court.

The presidential election results have many taking stock of past victories and future controversies. It seems reasonable to think that at some point over the next four years, a work of art could again find itself in the government’s crosshairs. “While it’s not predictable where challenges are likely to arise in the next four or eight years, it is predictable that there will be challenges to the arts generally, to museums particularly,” Abrams said. Thinking about the future, Siegel looks back to the past, on his experience in the civil-rights era South, working with black and white activists and lawyers. “They always taught me that you have to fight back,” he told me. “You have got to to try to win, but sometimes just fighting back is empowering. And you can’t be silent.”

—Isaac Kaplan

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)