Moonlight Etchings of the Forgotten Artist who Taught Edward Hopper

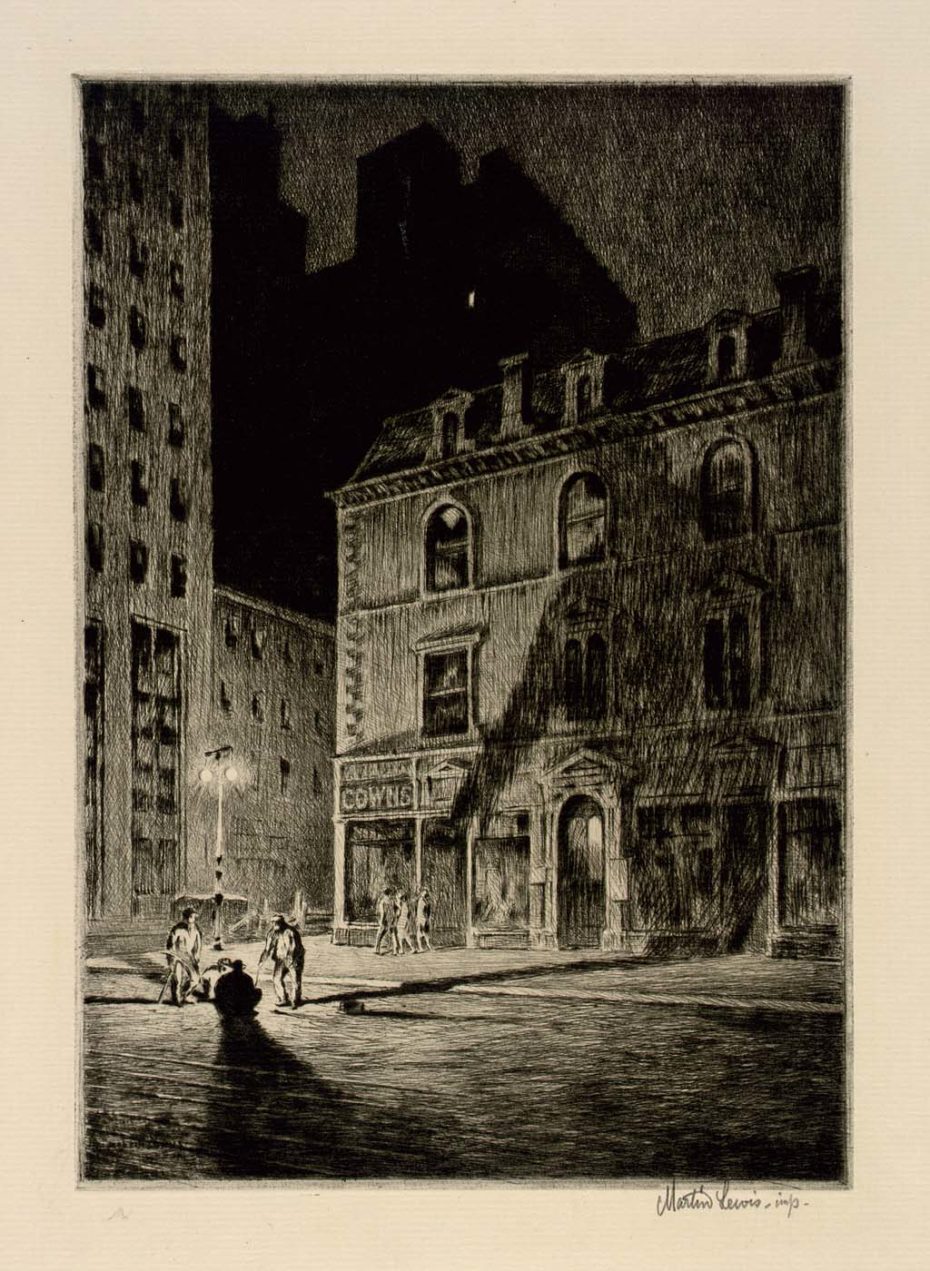

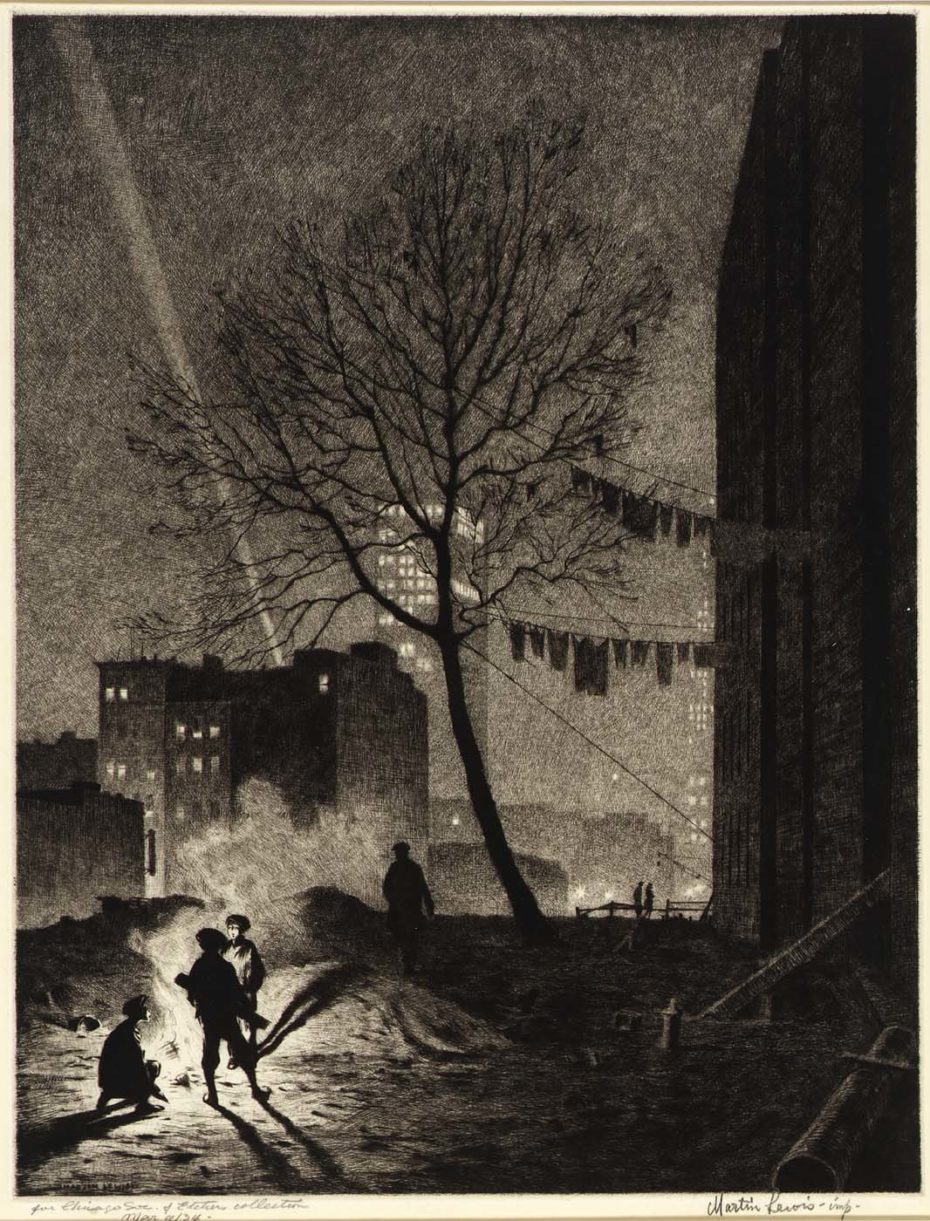

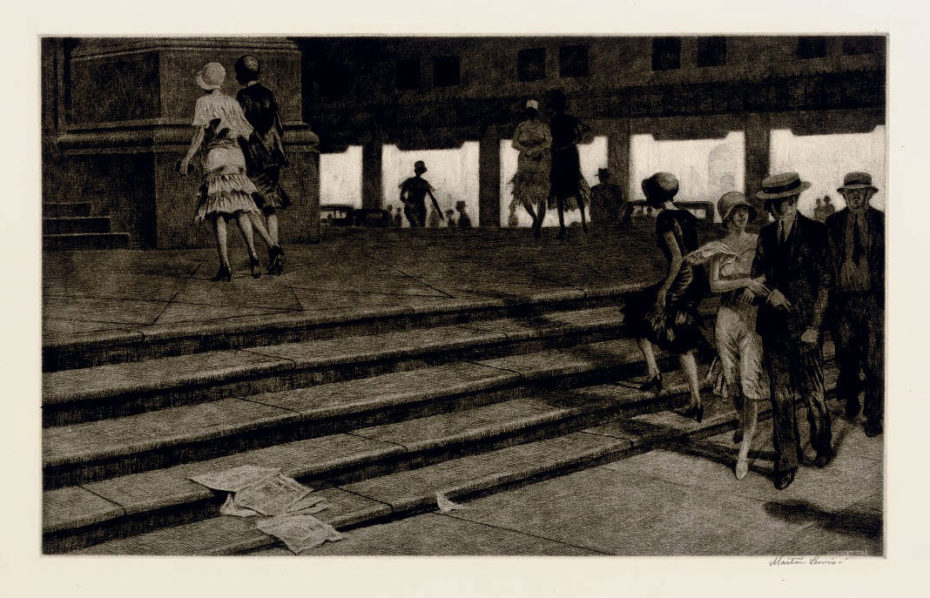

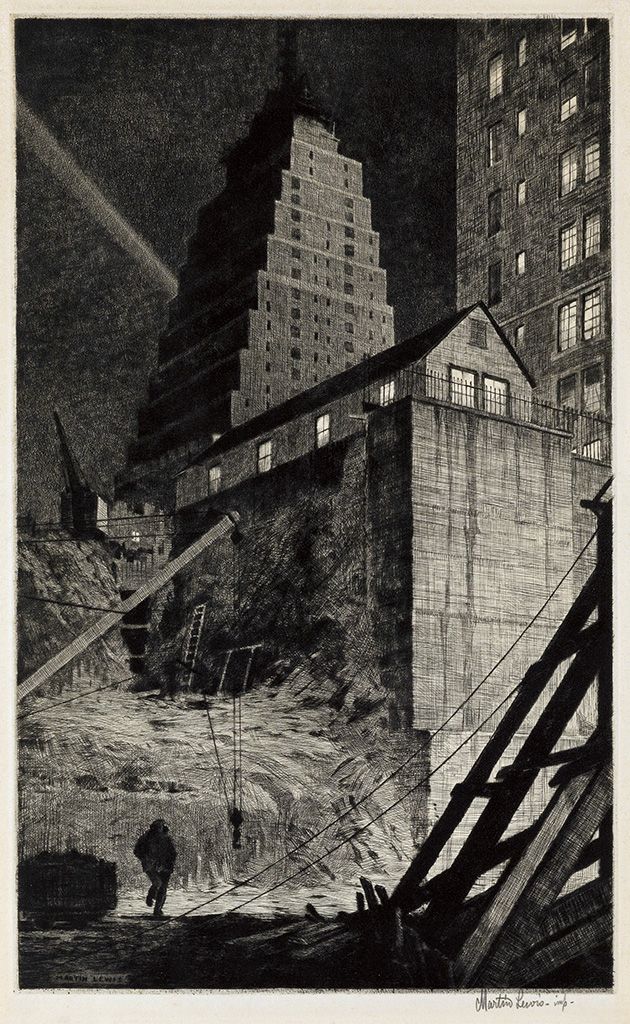

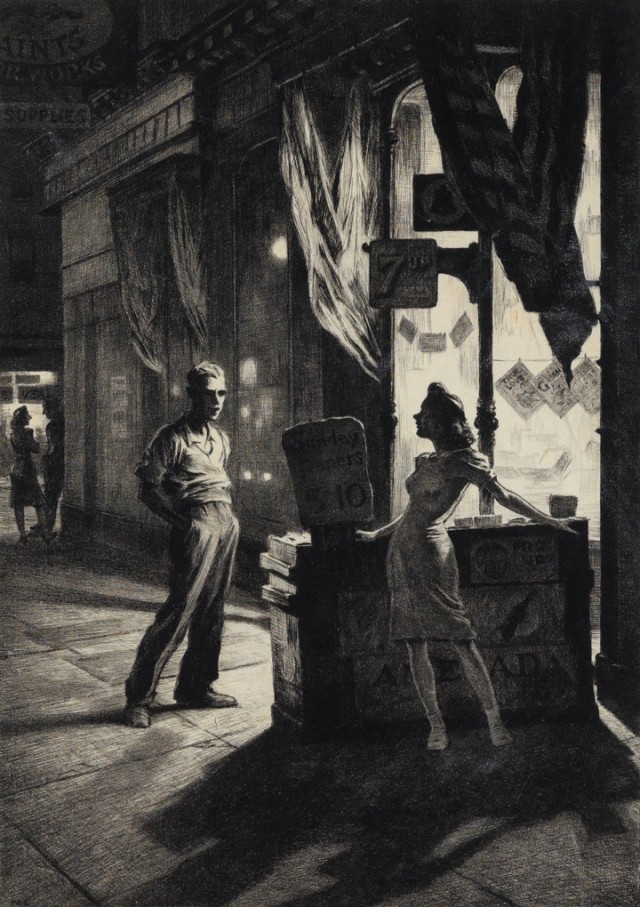

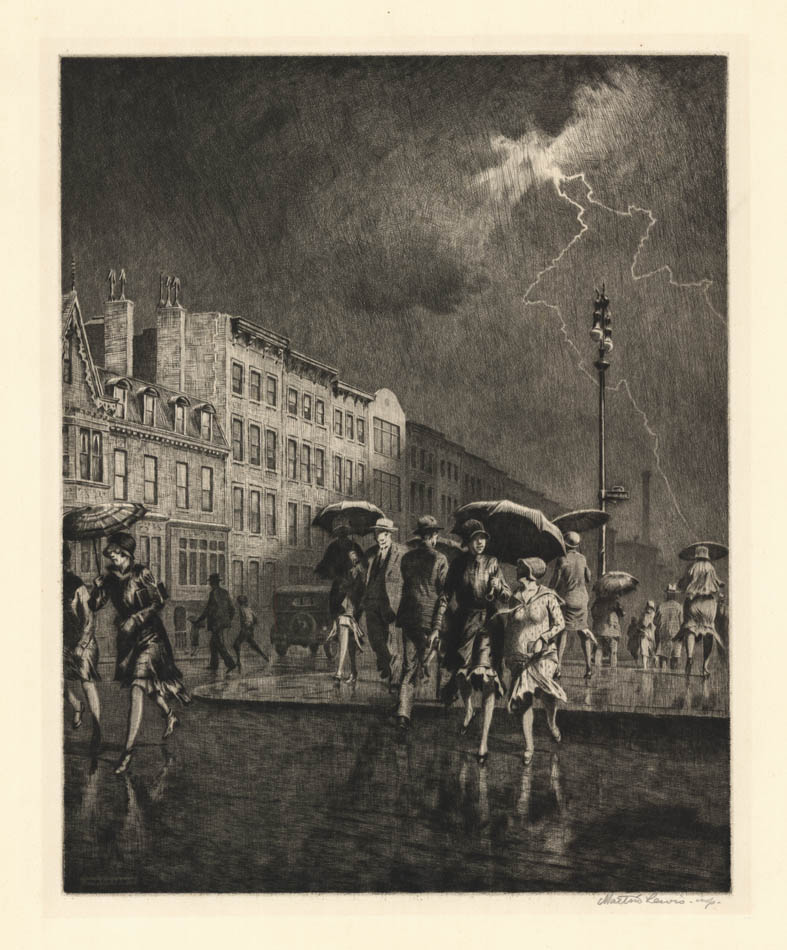

Martin Lewis died in obscurity in 1962; a retired art teacher who had found some success in his early career, but was largely forgotten after the Great Depression took away the demand for his craft, leaving Lewis to spend his last three decades teaching other people how to etch. History chose Edward Hopper, but Martin Lewis was his mentor.

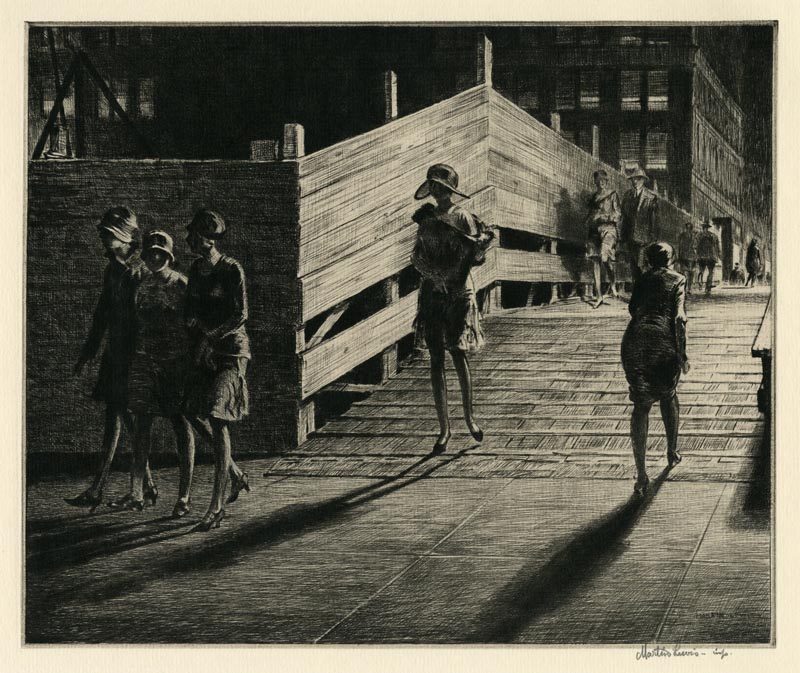

“After I took up my etching, my painting seemed to crystallise,” Hopper is quoted in his biography. It was Martin Lewis, an Australian emigré who had moved to New York in 1909, that helped Edward learn the basics of etching. The two became good friends on the artists circuit where eachothers’ work was presented to the public at various art clubs and small exhibitions.

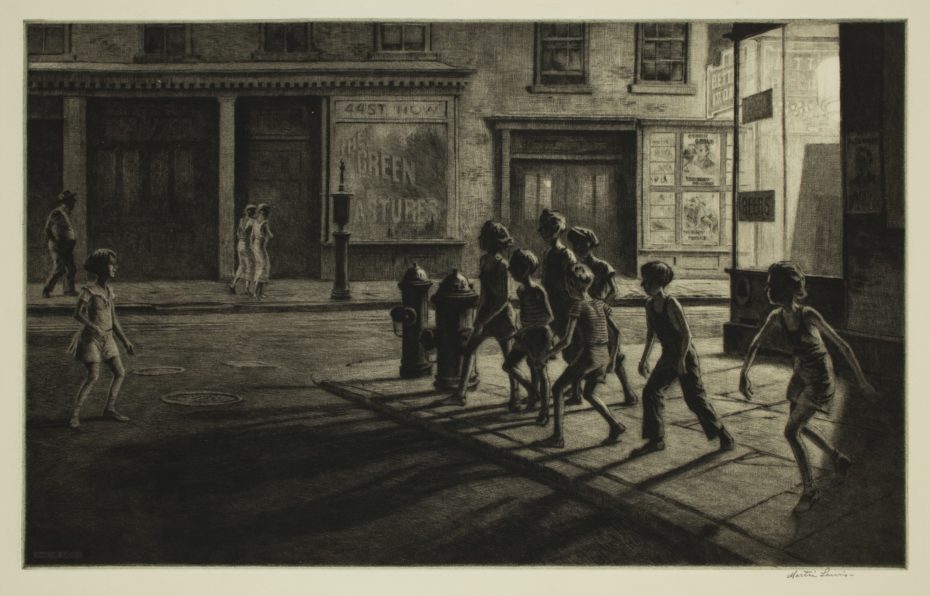

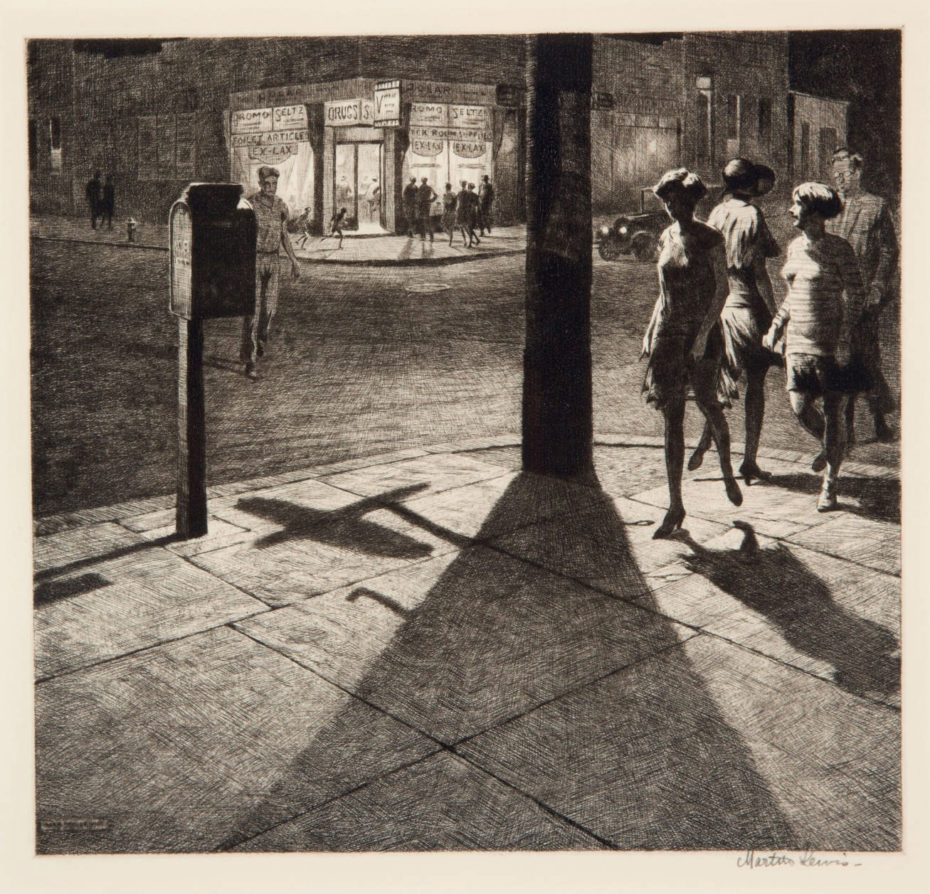

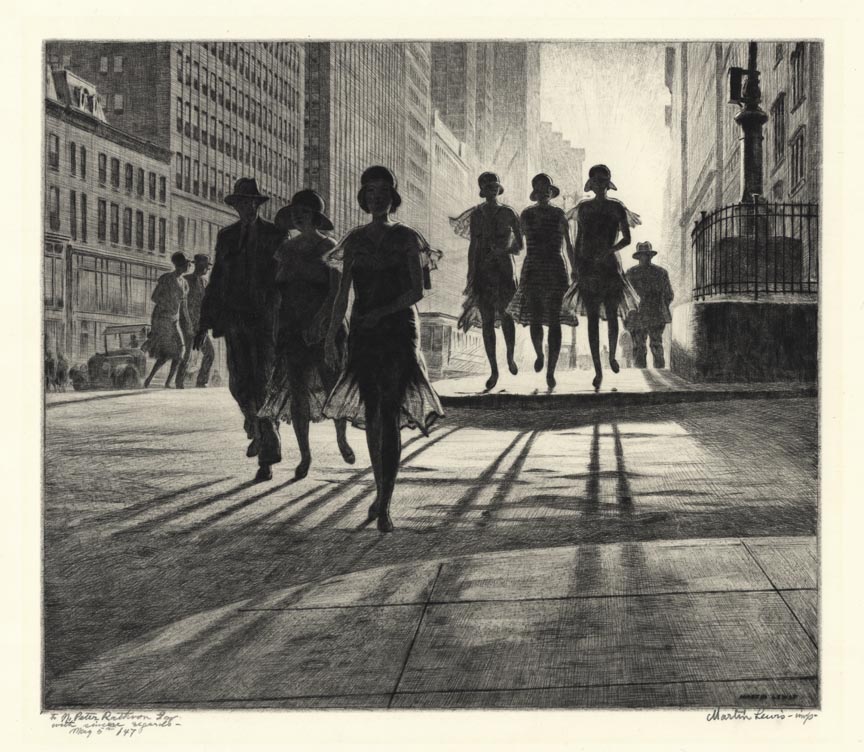

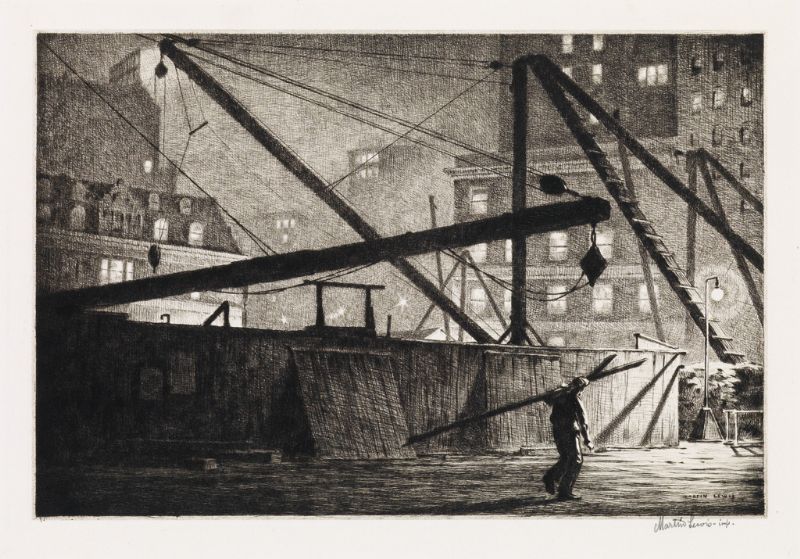

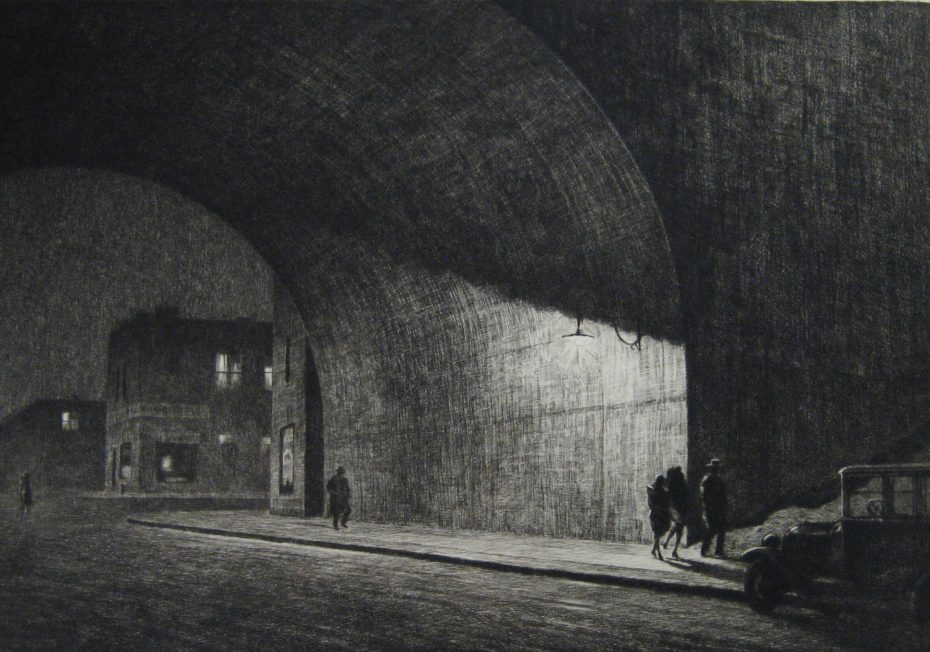

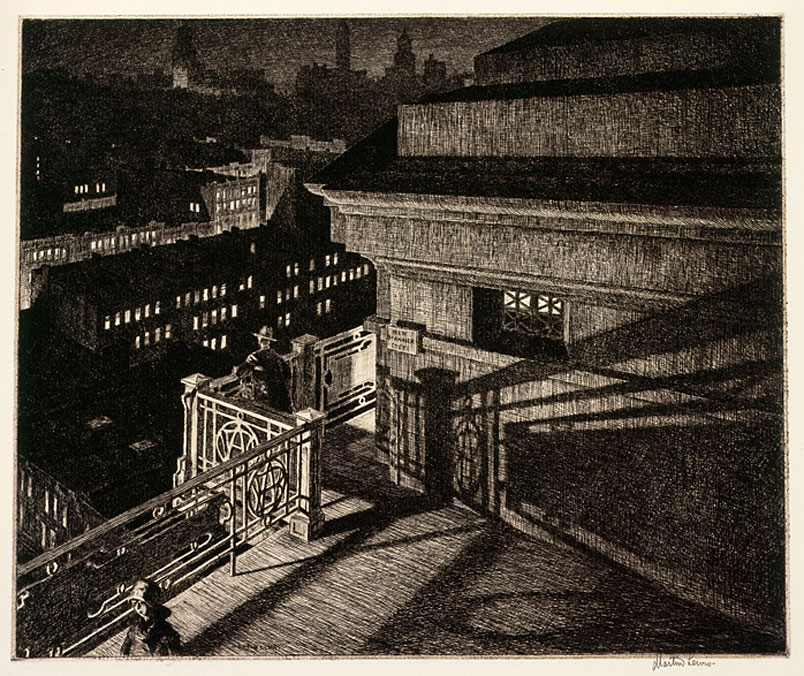

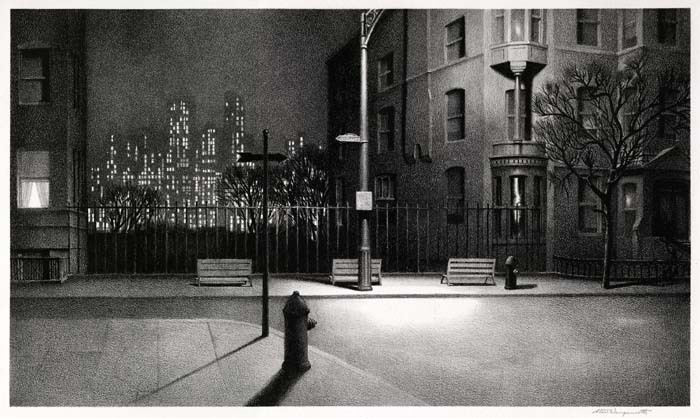

Lewis had taken up printmaking by 1915 and was using the etching press to produce prints which became widely admired and collected by the East coast elite. While making a name for themselves in New York City, Hopper asked his friend if he could study alongside him to learn his techniques, making Lewis his mentor for a brief while. As his student, Hopper learned the finer points of etching and both artists used the great American metropolis at night as their muse.

Years later, when Hopper was preparing for a one-man show in Pittsburgh at the height of his career, he rejected the notion that Lewis’s work had influenced his own or that he had studied “under Lewis” as implied by the exhibit’s biographical essay. “Lewis is an old friend of mine,” he countered. “When I decided to etch, he, who had already done some, was glad to give me some tips, on the purely mechanical processes, grounding the plates, printing etc”. By this time, the two artists were no longer friends however. According to Edward’s wife Josephine, Lewis and his wife Lucille had given the Hoppers up, “quite understandably. It had been too much of a blow to have E.H so successful.”

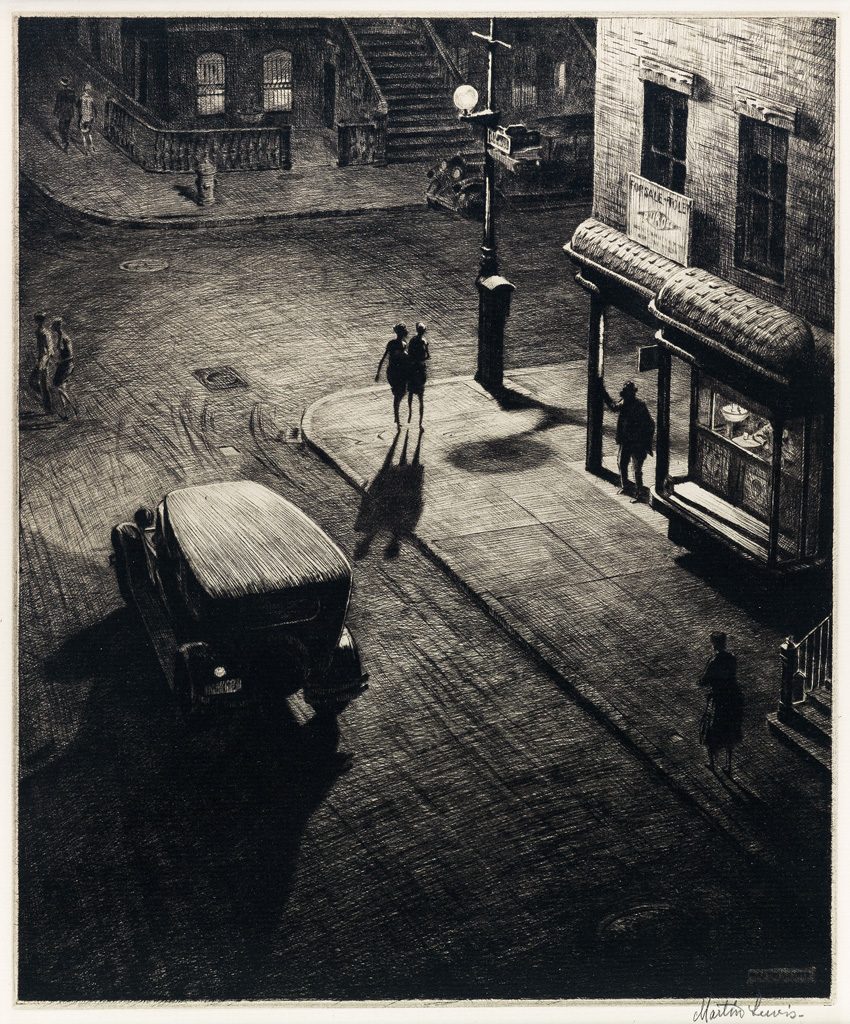

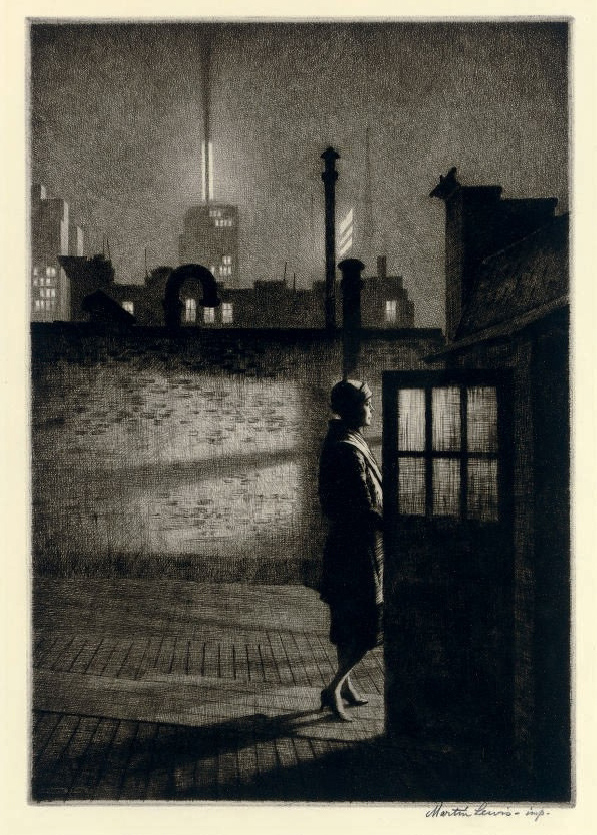

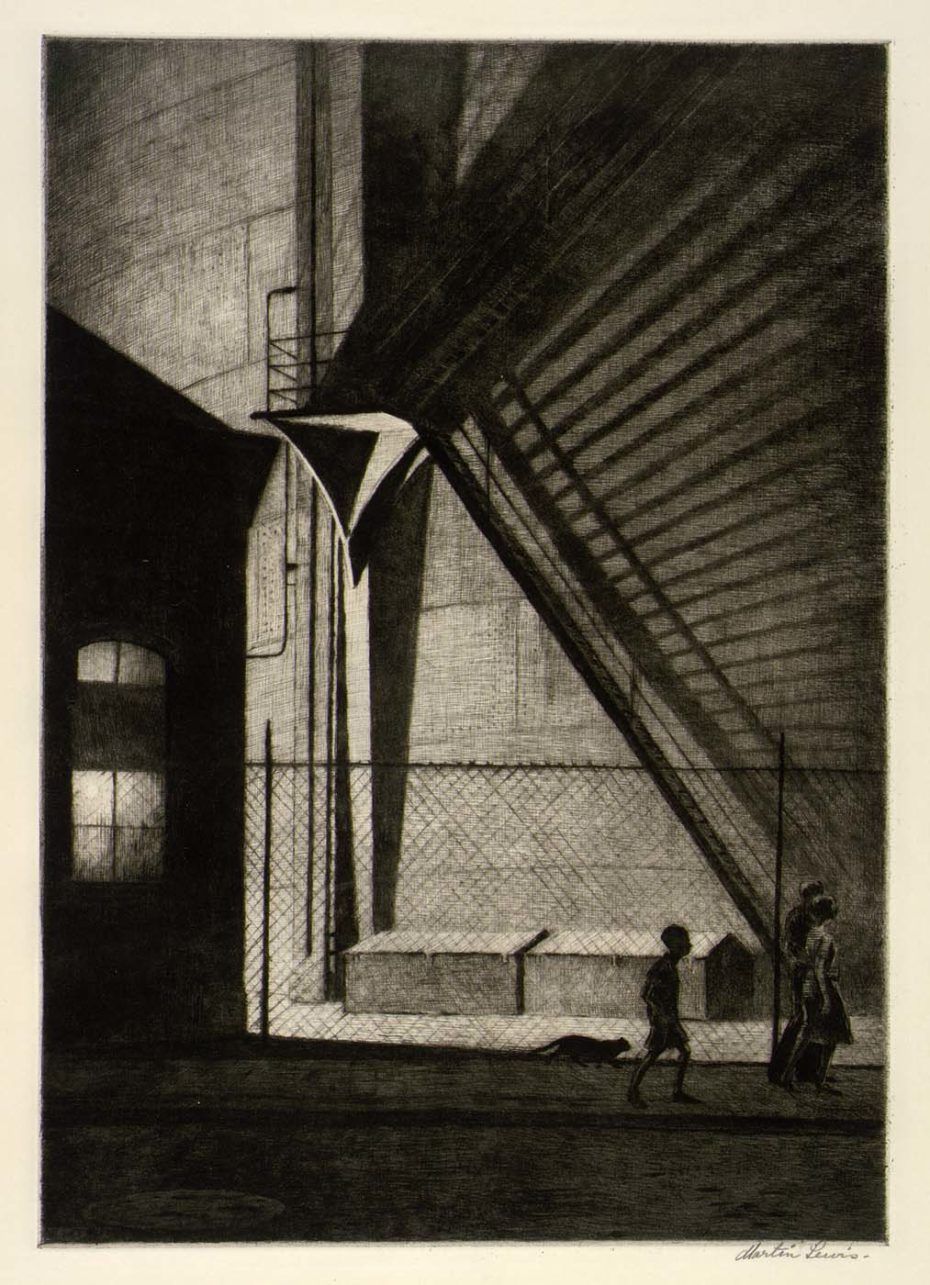

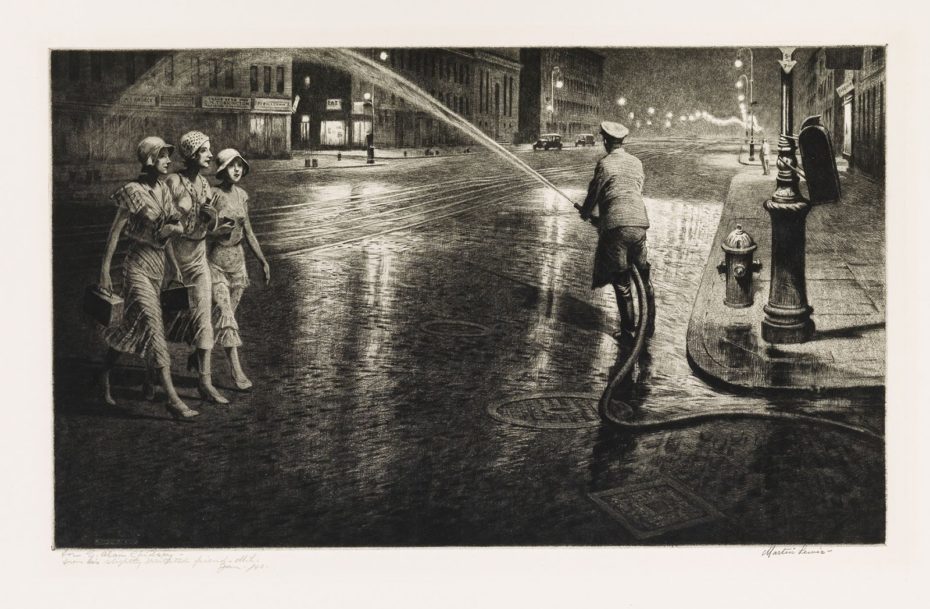

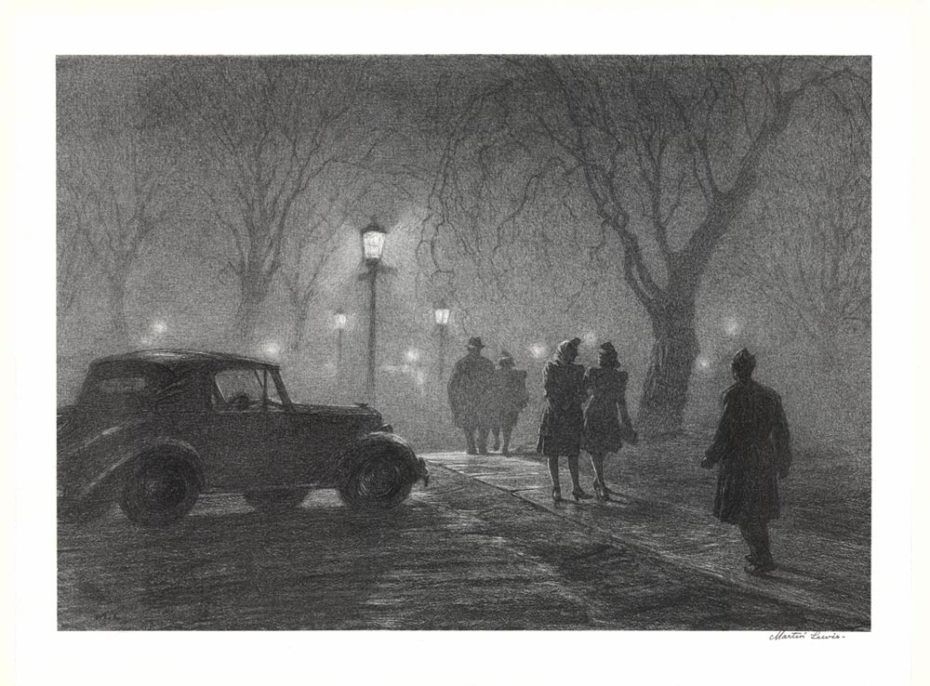

Nearly 50 years after his death, Lewis’s print, Shadow Dance (pictured above), sold for $50,400 at an auction in New York, setting a record price for the artist at auction. He had found a renewed, posthumous appreciation in the new millennium, whereas decades earlier, auction houses couldn’t sell off his prints at all and entire lots failed to reach their reserve price.

Much of his work may yet to be discovered. In 1920s, he was supported and collected by numerous etching societies and museums, but so many works are now held privately, out of public view. We would love to see more, wouldn’t you?

Prints for sale can be found on The Old Print Shop.