Art

The Taboo History of Women’s Body Hair in Art

Titian

Venus of Urbino, 1538

Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Women think a lot about their body hair—and how to get rid of it. Judging by the multi-billion-dollar success of the global hair removal market, female body hair is still a taboo, one that has dominated Western culture for eons.

Last year, the women’s shaving start-up Billie broke with a century of tradition with an ad campaign featuring women shaving hairy legs, an apparently radical departure from the women dragging razors over perfectly smooth, airbrushed ones in Gillette’s long-running Venus commercials.

Marble statue of Aphrodite, 1st or 2nd century C.E. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

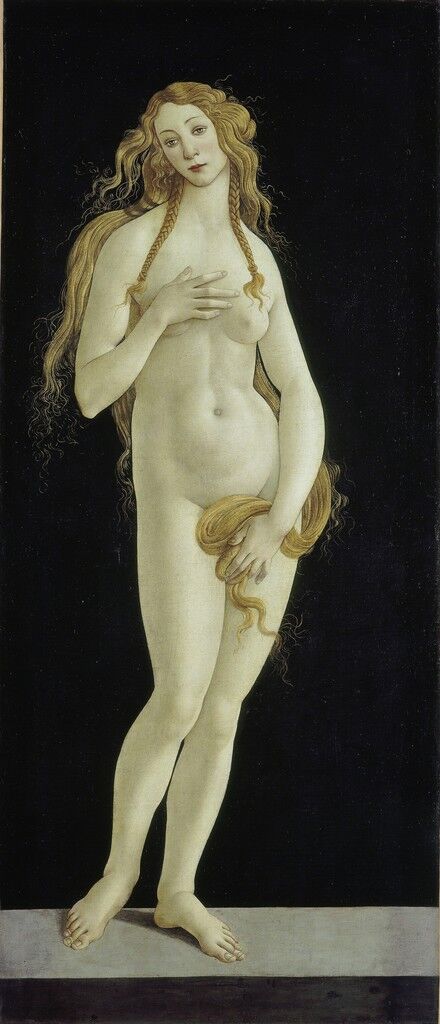

Sandro Botticelli

Venus, 1490s

The media’s adulations seemed to announce that a new era of openness was upon us. As art historian Jill Burke wrote, “Research into women’s personal grooming habits is, in many ways the study of systems of inequality…a woman’s body is imperfect unless it is somehow modified.”

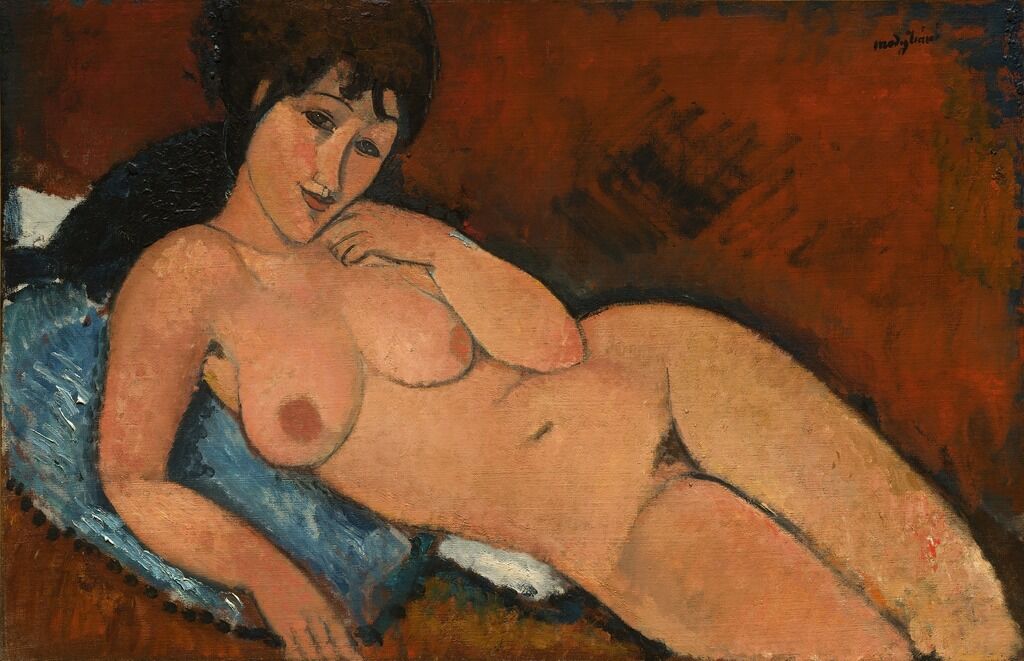

More recently, female body hair has gained a political resonance as many women today forego shaving as a feminist or fashion statement. Feminist artists such as

chose to engage with the body in paintings that strove for honesty. Her 1968 portrait of artist

shows her reclining, odalisque-style, on a couch, unperturbed by her prominent patch of dark pubic hair.

Still, archaic ideas around body hair remain hard to break. The feminine beauty standard of “the hairless ideal” has been molded and reiterated by male artists since ancient times. Female body hair was considered barbaric, uncivilized, or low-class in Greek culture. Recipes to remove hair—from plucking to shaving to sugar waxing—have existed all over the world for thousands of years.

Historian Alice Macdonald observes that in

, the “smooth marble bodies” of their sculptures, “whether hairless because of artistic censure or because they reflected the social custom of depilation—have over the centuries structured the cultural imagination in such a way as to make the glabrous female body an entrenched and irresistible feminine aesthetic.” By contrast, male nudes from the same period have hairless chests, but unlike their female counterparts, sport stylized pubic hair.

’s fourth-century sculpture of a female nude, called the Aphrodite of Knidos, is often considered the origin for some of the most persistent tropes in art and culture about women’s sexuality. The marble goddess places her right hand over her pudendum, chastely covering it while at the same time pointing to her sex. Aphrodite’s sensual pose came to be known as the Venus pudica, and has been endlessly riffed on for centuries. When

ideals and an interest in the human body were revived in Europe during the

, artists returned to the hairless Venus.

In

’s Venus of Urbino (1538), a beautiful nude woman lies supine on a divan with disheveled sheets. Her hand lightly hovers over her smooth pubic region. Macdonald explains, “The marble-like texture of her nude body—so reminiscent of ancient sculptures—suggests that her body is hairless and that the darkness that can be seen between her legs is shadow rather than body hair.”

The Three Graces, Roman copy of the Imperial Era (2nd century C.E.?) after a Hellenistic original. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Venus’s sexuality and missing pubic hair is further invoked by the sleeping dog curled at her feet. This furry addition reflects another long-held belief about the correlation between women’s body hair and eroticism. In ancient Greece, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance, hirsute women were often considered wild or sinful and thought to possess an untameable sex drive.

In one narrative about the Queen of Sheba, amply represented in art from Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, King Solomon forces his exotic visitor to shave her legs before he beds her. The detail about her hairy legs, Alina Cohen wrote for Artsy, “portrays her as an animal—a heathen—to be subdued, feminized, and converted.” In the Medieval Christian artistic tradition, the image of a woman completely covered by her long hair is usually the repentant prostitute Mary of Egypt.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Girl with a Dog, 1770. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Were the real women of the day as suspicious of their body hair? Historian Sandra Cavallo has noted that in the 16th century there was an “explosion in treatments for facial appearance,” evidenced by the many “books of secrets” left behind; they share DIY cosmetic advice on how to remove hair from every part of the body (all while keeping the hair on one’s head luscious and thick!).

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, especially in France,

“revived” the ideals of the Greco-Roman tradition. The French bred a culture with a heightened sense of eroticism. Artists like

played with euphemism in his works, but didn’t stray far from the tropes that had been defining women’s sexuality for hundreds of years. In his painting Girl with Dog (ca. 1770), Fragonard mischievously displaces the female subject’s sex with a little dog over her exposed genitals; her pet’s tail stands in for her pubic hair.

In this increasingly modern era, Michel Foucault argues in Discipline and Punish (1975), there was an “emergence of unprecedented discipline directed against the body” in the second half of the 18th century. Cosmetics, dieting, and depilation, became de rigueur, self-governing practices that continue to regulate women’s lives today.

Two kinds of artists emerged in Europe and the United States in the latter half of the 19th century: those who would continue the staid conventions of the state-sanctioned Academies and those who would fight to break their rules. Salon-approved paintings by artists like

and

are sickly sweet and ridiculously idealized. Perhaps unsurprisingly, both artists took on the Venus theme in their work. Bouguereau’s The Birth of Venus (1879) almost parodies

’s famous version. Venus stands on a clam shell jutting out from the sea but instead of chastely covering her pudendum, she here throws her hands over her head—all the better to view her hairless, sexless genitals.

Artists from the same period who engaged with the fashionable but problematic trend of

, like

and

, applied Western beauty ideals of hairlessness to their exoticizing pictures of Middle Eastern and North African women. They delighted in the opportunity to portray these figures as literal sex objects—nude in the bathhouse of a harem (The Turkish Bath, 1862) or on the auction block as a sex slave (Slave Market, 1866). Even though they are not couched in Classical allegory, these women were still refused their body hair.

Contrast these paintings with works by avant-gardists like

,

, and

, artists preoccupied with capturing modern life, especially the public specter of prostitution. Manet’s Olympia (1863) famously upends the Venus pudica pose of Praxiteles and Titian with a sex worker who openly acknowledges the transactional nature of her trade with the viewer.

By the late 19th century and early 20th, the idea of women’s body hair as a sign of wild sexuality became more illicit. In an ironic twist, artists began to include women’s pubic or underarm hair in their works to emphasize their sexuality. Underarm hair was not seen in public, so it was especially erotic in art.

’s L’Origine du monde (1866) is the ultimate pro-body hair statement but it’s his Woman in the Waves (1863) that offers a less aggressive, more sensual view of unexpected hair. A Venus-like nymph relaxes in a pool of water, her arms lazily perched on her head—a pose that serves the dual purpose of lifting her perky breasts and exposing her hairy underarms.

At the same time, certain modern artists clung to the sanitized version of women’s sexuality that demanded they be clean shaven even as society opened up around them.

is perhaps the biggest offender of this view of female nudity. His Bather Arranging Her Hair (1893) is essentially the same painting as Titian’s Venus Rising from the Sea (ca. 1520), made hundreds of years earlier.

Overall, these changes in modern art were reflected by the consideration of women’s body hair in popular culture. In response to the rise of sleeveless dresses at the turn of the century, Gillette released the Milady Décolleté, the first razor marketed to women, in the United States in 1915. The same year, Harper’s Bazaar ran a scandalous shaving ad in their May issue; a model in a sleeveless dress throws up her hands. Lo and behold, no armpit hair.

In our current century, more and more women—and men—wax, thread, shave, or laser themselves bare. No matter how women choose to present their hair, the uncomfortable fact is, we have it. Our society and our beauty ideals might have followed a very different course if artists had been more open and faithful to the true perfection of the female form, body hair and all.

Julia Wolkoff is an Editor at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment