This piece is the second in a two-part series that analyzes the future and sustainability of the gallery sector through the lens of professional sports. We recommend starting with Part I.

Like commercial galleries, professional sports leagues receive a lot more attention for what they produce than for how they’re structured, or why. And yet it’s remarkable how differently the two industries have evolved over nearly the same timeline, at least here in the US. The grand irony is that, despite a few years’ lead, the gallery system today is far less professionalized than any of the major American sports—and, I would argue, far less sustainable as a result.

Red Grooms, Home Run Sculpture at Miami Marlins Park during a preseason game against the New York Yankees in April 2012. Courtesy of Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images.

Head to Head

Let’s compare, shall we?

Knoedler, among the first commercial galleries founded on American soil, opened in New York in 1846. It wasn’t until 25 years later, in 1871, that the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players became the game’s original “major league”—and the first true pro sport in the US (contributing to its status as “America’s pastime”). This association would eventually morph into the National League, whose champion met the winner of the upstart American League in the first World Series in 1903.

What has transpired since then? Major League Baseball (MLB), as the two conjoined pro leagues are now known, consists of 30 individual franchises overseen by a central commissioner and governed by a

373-page agreementcovering everything from player transfers to revenue sharing to a robust talent development system (AKA the minor leagues). Overall, MLB generated over $10 billion in revenue in 2017, and it continues to serve as the model for baseball leagues now operating in 122 countries around the globe.

In comparison to this buttoned-up profile, the gallery system comes across like the type of sweat-streaked, wild-eyed “entrepreneur” who offers to “get you in on the ground floor” of some nebulous enterprise from the darkened corner of a dive bar.

Again, we have no reliable revenue numbers or other operational data for galleries, thanks to the fact that every known one of them remains privately held. Although all typical commercial laws apply to the trade, its only internal codes of conduct remain siloed within voluntary professional associations, such as the

Art Dealers Association of America, or by-application-only events, such as

Art Basel.

We’re not even really sure how many galleries and dealers there

areworldwide, given that the last time we had two reports to judge from, their estimates differed by about 600 percent. (

UBS and Art Basel’s 2017 reportestimated over 296,000 private sellers, while the

TEFAF Art Market Reporttallied only about 51,000.)

Most importantly, while the disparate franchises in MLB thrive together, an entire tier of galleries—as well as many of the non-star artists they exist to champion—are being pummeled into submission by recent conditions, threatening the stability of the entire ecosystem.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Regardless of the many differences between pro sports and contemporary art, the former provides a framework for how to build a niche collection of like-minded business owners into a sustainable network that serves each member’s different needs and incentives.

George Steinmetz, New York Air. Photo by George Steinmetz, courtesy Anastasia Photo.

The Game Plan

Changes on this scale don’t happen overnight—or even over a few years. It took about a century for Major League Baseball to morph into the sleek organizational juggernaut it is today. The sport’s two major divisions—the American League and National League—technically didn’t merge into a single legal entity until 2000, although they operated in harmony for decades before.

In short, I’m not suggesting that the gallery sector follow in the footsteps of an impossible ideal here.

Without tracking every twist and turn in the saga, what enabled professional baseball to flourish was a process called collective bargaining.

The idea is straightforward: Large groups empower a few trustworthy representatives to negotiate on their behalf in pursuit of terms that everyone in the collective can live with. Those terms get ratified in a mutual, publicly available contract that runs for a handful of years, after which the sides re-engage to hammer out a new collective bargaining agreement informed by how well (or not) the last one worked.

Today, every major American professional sport runs on the path cleared by collective bargaining. For each league, the agreement guiding the business represents a compromise between the owners and the players’ union. All of this is enabled by what’s generally referred to as the “league office”—basically, the internal oversight body created to facilitate and, when necessary, enforce the terms of the collective bargaining agreement on both sides.

Now, it would be ideal if artists could become the equivalent of the players’ union in this comparison. It would also expand the potential impact of any collective bargaining agreement, since, legally speaking, I don’t believe regulations on artist-specific issues (like anti-poaching protections) could be enacted unless the artists are involved in the negotiations.

But while I think it would be to artists’ advantage to organize, their participation doesn’t seem to be strictly necessary for substantial gallery reform on other subjects of consequence, like the possible creation of revenue-sharing pools or even a cooperative “minor league” system of the kind presaged, perhaps, by the

partnership between Metro Pictures and 47 Canal.

Instead, the parallel that matters is the one between the owners of pro sports franchises and the owners of galleries, not least because both deal with some of the same inherent tensions.

William Klein, Baseball Cards (1955). Photo: artnet.

Family Feud

While anyone who owns a controlling share in a pro team in 2018 is hugely wealthy by almost any other standard, the key is that there are significant gaps separating owners within their own ranks. The most crucial of these is the one between “big market” and “small market” or “mid-market” cities—a distinction useful for imagining compromises between high-end and mid-tier or emerging galleries.

How does that distinction materialize in practice? Broadly speaking, the owners of the New York Yankees want certain aspects of baseball to be regulated differently than the owners of, say, the Kansas City Royals.

For example, the Yankees would argue against implementing compensation payments to any franchise whose players get signed away by another team at the end of their contract, because they are one of the most likely franchises to have to pay that compensation. The Royals, whose smaller market (and smaller cash reserves) makes them less likely to acquire top free agents, would take the opposite side.

The larger point is that these schisms between the richest franchise owners and the less well-off tear open anew—and must be mended again—every time a new collective bargaining agreement needs to be written. In some cases, these divisions between owners can be as extreme as the ones between the owners and players.

Christian Marclay, Still from The Clock (2010).

Crunch Time

This is where the league office comes in—or more specifically, the commissioner, whose entire job consists of facilitating the continued growth and smooth function of the sport as a whole. These duties naturally include making peace between ownership factions, which can only be done when everyone involved agrees (however begrudgingly) that the league’s bylaws are working for them.

Of course, it’s not as if the commissioner of any pro league descended from the clouds on a ray of light and imposed order on a cabal of resistant owners. The owners themselves had to decide to establish the league office and select a smart, talented, and experienced professional to run it. What they didn’t have to do was resolve their internal disputes and competing interests all by themselves. They just had to agree it was crucial for the overall business’s sustainability to find someone else to help them do it.

The gallery sector has reached this same crossroads. A mega-gallerist could craft the most brilliant, elegant fix to the system imaginable, but this magical solution would evaporate into the ether if it were simply proposed from the stage of a conference and

casually discussed in the aisles of the next art fair. To make change real, the gallerists themselves need to organize in a dedicated way.

How does this happen? The obvious origin point would be the existing professional associations at different levels of the market and in different geographical regions: the ADAA, NADA,

Comité Professionnel des Galeries d’Art, and others.

If each of these organizations elected a few representatives to carry forward the concerns of the different factions within their larger group, collective bargaining sessions could be facilitated. The reps could then take the results of those sessions back to their constituencies for reactions and refinement. Wash, rinse, repeat until everyone discovers enough common ground to formalize a possible agreement.

Maybe these collective bargaining sessions would be overseen by an impartial arbitrator—a proto-commissioner of sorts who understands the incentives and challenges facing the full cross-section of galleries. Maybe they should also include representatives from the various art fairs, given how critical (

and controversial) those events have become to the trade. Or maybe all you need is a closed-door meeting with a quorum of gallerists dedicated to moving the ball forward on a handful of universally important issues.

Questions about the exact parameters of these meeting aren’t what’s preventing them. A lack of vision and a lack of commitment are. Everybody loses if no one ever gets on the field.

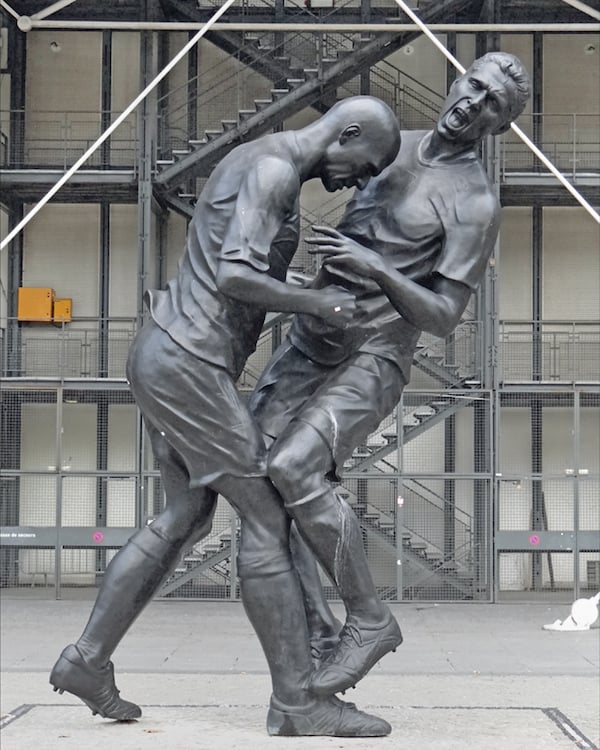

A man stands on baseball bats in an untitled piece by American artist David Adamo on October 23, 2013 in Paris at the FIAC International Contemporary Art Fair. Photo: Francois Guillot/AFP/Getty.

Upon Official Review

Now, I can anticipate the criticisms about micro-management, corporatization, and my own naiveté. How preposterous is it to believe that a collective of gallerists with different interests could even agree on which restaurant to meet at, let alone how to solve problems as complex as the middle-market massacre?

Well, first off, rival owners in every American pro sport did it decades ago. There are plenty of other precedents, too. Again, forms of collective bargaining power industries as varied as teaching, manufacturing, Hollywood filmmaking, and yes, even

museum work. These are hard problems, but it’s not like we’re trying to terra-form a new Earth here.

Second, it’s either ignorant or disingenuous to act as if implementing a limited set of mutually beneficial, common-sense regulations is the same as turning the gallery sector into a soulless, mechanized dictatorship. Buying into these types of false equivalencies is exactly how you paralyze an ecosystem being pillaged by changing environmental conditions.

Besides, if galleries are truly being obliterated unnecessarily by a broken system, why should we hesitate or half-step on reform? Call me crazy, but I’m willing to let the pilots try anything they want, as soon as they want, if all the evidence tells me that letting the plane stay on its current course will crash us into a mountain.

George Kalinsky, Patrick Ewing and the Knicks win the NBA Eastern Conference Championship, June 5, 1994. Photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

The Will to Win

Although we should never forget the impact of a

dramatic shift in buyer behavior, galleries have nevertheless reached the present crisis partly by choice, and choice is the only thing that can extricate them from it.

Art sales will continue with or without reform. It’s just a matter of whether they will happen in a healthy, sustainable ecosystem, or whether the mega-galleries will completely monopolize the trade through brute-force acquisitions of smaller galleries and the creation of vertically integrated talent pipelines that begin in leading MFA programs and end in the white cube—

an all-too-real future I’ve written about elsewhere.

Remember, the actors with the least incentive to change are always the ones succeeding as things are.

Still, even at the apex of the gallery hierarchy, there’s a growing awareness that recent trends could be bad for business, perhaps sooner than later. For example, top sellers definitely have the resources to establish entire departments (and likely, separate spaces) for the development of young artists. But I’m also convinced that they don’t want to spend the time and money required to do so unless it’s absolutely necessary (or at least, cheaper and more efficient than continuing to use mid-tier galleries as an organic feeder system).

If gallerists across tiers are cognizant enough of the industry’s structural problems to debate

a band-aid solution like an art-fair tax, then, let’s hope they’re just as serious about engaging on an unprecedented set of changes that could actually put the trade on a path to sustainability. Even if the rest of my proposal strikes you as asinine, one lesson from pro sports is undeniable: Despite all other factors, sometimes what matters most is the sheer will to push yourself beyond your old limits.

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.