Galleries

What Will the Art Gallery of the Future Do? Pace’s Marc Glimcher on the Coming Disruption and Why the ‘Art World Is Not Fair’

artnet News's Andrew Goldstein spoke to the international gallery's CEO about the growing importance of "experiences."

Last month, I had the opportunity to talk to Pace Gallery president and CEO Marc Glimcher about where the art industry is headed and the disruptions around the corner. It was appropriate, in a way, that the talk—part of the inaugural Frieze Los Angeles art fair—took place at Paramount Studios, since Paramount is a poster child for the kind of disruption that has been spreading through the culture industry at large.

One of Hollywood’s great studios, Paramount was a cinematic behemoth in the 1960s and ‘70s, turning out classics like The Godfather and Rosemary’s Baby at an impressive clip; these days, it’s fighting for survival—all because it failed to adapt as the industry evolved from DVDs and theatrical distribution to the age of streaming. This kind of disruption has hit every industry, from film to music to media to book publishing, and you can separate the winners from the losers by looking at who was able to adapt before it was too late.

The art industry, meanwhile, has proven stubbornly resistant to disruption. During the art fair, which was taking place on the other side of the Paramount lot, you could find booth after booth fitted with sculptures and paintings sold by dealers to collectors to put above their sofas, in storage, or maybe in a museum. Although the subject matter and the mode of manufacture of the artworks may be cutting-edge, its basic format—as painting or sculpture—and the business model used to sell it would have been largely recognizable to people in 1960, when Arne Glimcher first founded the Pace Gallery.

Pace Gallery president and CEO Marc Glimcher. Photo by Kris Graves, courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Today, run by Arne’s son Marc, Pace has grown into one of the biggest galleries in the world, with 10 locations internationally—which draw about 4,000 visitors per week—and a roster of dozens of seminal artists and estates. Pace rests upon a storied history, but it is also, perhaps more than any other gallery of its size, taking steps to anticipate dramatic changes in the field’s future. And in fact, art may be on the precipice of major transformation.

The conversation with Glimcher follows below. It has been edited to suit the Q&A format.

Store Days II, Ray Gun Theater performance at The Store, New York (1962). Photo: Robert McElroy/The Getty Research Institute

I’d like to talk to you about where art is going, but let’s start by going back in time. There was a moment in history several decades ago when it looked like art was going to take a turn away from painting and sculpture to something more hybridized and experiential. What happened?

When I was a kid in the 1970s, we were told that painting was dead. And that didn’t literally mean that people were going to stop making paintings, but it meant that the leading edge of art was being advanced by artists who referred to their work as phenomenological—not something to be purchased by a wealthy person and shown on a museum wall. A lot of this was coming out of the Happenings era, and was circulating among Robert Irwin’s students at CalArts.

But we dealers didn’t offer any business model [for experiential art to be financially viable in its own right]—and, lo and behold, painting came back! What a shock. It came roaring back in 1980s, and it has progressed since then in very powerful ways.

James Turrell editions at Pace Prints. Image courtesy of Pace.

What is the business model they were not offered?

The only business model for experiential art is one that is linked to a very large audience—if art experiences are linked to a small audience, it’s not business, it’s philanthropy. Art cannot survive on philanthropy alone, and never has.

So then what’s the business model for experiential art that is not philanthropy?

Well, [Pace executive vice president] Peter Boris came to me about five years ago and started showing me the work of some artists, particularly teamLab, and they knew what the model is—which is that you sell tickets. But in our world, you only sell tickets as a donation to a nonprofit—anything else is is considered debased. It’s okay to sell tickets to a movie, dance, music, or theater performance, but not art.

The funny thing is that people, for the most part, have no problem paying to visit museum or an art fair. What’s inconceivable is the idea of buying a ticket to see art in a commercial gallery.

[If a gallery were to charge tickets to an experiential show] people might think, “Ah, that’s how the art dealer gets paid.” No, that’s how the artist gets paid. Right now, the general public is not permitted to pay the artists. They pay institutions, which are supported by ultra-high-worth-net-worth individuals, and those institutions bring wealthy people’s art to a place where everyone can visit it in exchange for making a small donation. There are no connections between the artist and the public.

Willem Dafoe as the Vincent van Gogh in Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate. (Lily Gavin / CBS Films)

It’s fascinating that, historically, there’s a lot of attention paid to people like Van Gogh—artists who lived in poverty and died in obscurity, only to be lionized later on—but less attention paid to the crucial role that a business model typically plays in the creation of art. Because if you have a business model that supports making paintings, people are going to make paintings. If you have a business model to create something experiential, people are going to do that more often.

Actually, it’s really is the other way around. People make paintings and they are great, so a business model becomes attracted to them. Experiential art is very young and it is attracting a business model, even if that didn’t happen in the ‘70s—this has still been a relatively short period of time. And it will attract a business model because it’s creating something that there is a fundamental demand for in our world.

You recently had a teamLab show in your Palo Alto gallery where you were offering domestically scaled screen works that might give collectors a taste of their famed immersive productions. But what’s fascinating about teamLab is that I’ve heard these objects account for maybe 10 percent of their overall revenue, and that 90 percent of it is actually coming from the ticketed sales.

We don’t really talk about how teamLab makes their money, but we do know that millions of people around the world buy a ticket to see teamLab. They are not burdened by some old-fashioned idea about what artists are supposed to do and not to do. And we know that their practice—which now employs 600-plus people—is supported by the general public, not by a few art collectors.

teamLab’s Universe of Water Particles on a Rock where People Gather, 2018. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

A few years ago, you held three teamLab shows at Pace Gallery, in Palo Alto, London, and Beijing, and more than half a million people attended. Ticket prices were about $20, so if everyone was ticketed it would have brought in about $10 million. You’ve called this success a “proof of concept.” The trick with the art world, of course, is that it is tiny compared to other industries. That $10 million is roughly equivalent to what Beyonce and Jay-Z pulled in across a two-day concert at London Stadium last year. It’s also, incidentally, a fraction of what a single Rothko painting sale could bring in. How is it possible to find the scale that would make the ticking model work in a meaningful way?

It is important to understand that art does have an audience—that’s why museums are the biggest tourist attraction in every major city around the world. It’s really the uniqueness of the artist’s product that has kept it in a strange place. At Pace, we have 800,000 Instagram followers and 1,000 clients. And I’m even exaggerating by saying 1,000 clients, by the way. Who are those other 799,000 people? They’re people who are passionate about art.

Studio Drift’s Franchise Freedom drone ballet in Miami Beach, 2017. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

For a long stretch of its existence, Pace Gallery was known as a champion of rule-based abstraction, but lately the roster has seemingly evolved to put a new focus on younger artists who create immersive experiences as well. Here I’m thinking about artists like Studio Drift, JR, and Random International, the creators of Rain Room. When did that start to happen, and why?

It goes back to the 1970s, to a very foundational part of Pace Gallery. I remember when I was 11 years old, I walked into the gallery and there was just a white room, and after a few minutes I realized that one of the walls was sort of out of focus. This was Robert Irwin’s famous Soft Wall, where he stretched a scrim just six inches in front of the back wall of the gallery. That was a very formative experience for me. These kinds of artists are examining how to advance human perception in a very important way—and it needs a special kind of attention.

So when, five or six years ago, we started talking to artists at Random International and teamLab, we saw a kind of connection. They were absolutely passionate about Irwin, Turrell, De Maria, everything that had been done in that era—there was a kinship there.

Historically, the way you’ve supported these artists is by selling work that is peripheral—what you call “souvenirs.” With someone like James Turrell, for instance, you have done gallery shows of his holographic paintings, which are beautiful pieces but are fractionally important compared to the significance of something like Roden Crater.

Correct.

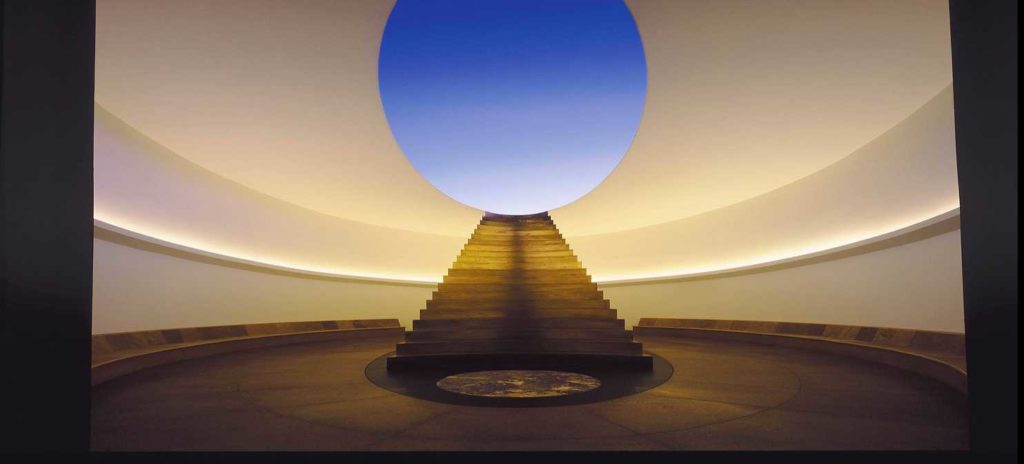

An interior view of Roden Crater. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

It’s extraordinary to think that Roden Crater, which Turrell has been building in Arizona’s Painted Desert as a unified experience of light, time, space, and water since the late ‘70s, is about to debut at the precise moment when people are desperate for this kind of in-person, be-here-now sublimity. Everybody is so consumed by screens constantly—there’s hunger to connect to something that makes you feel alive. What kind of impact do you think Roden Crater will have when it debuts?

The Crater has life-changing impact when you go. It does what art is supposed to do, which is that it makes large swaths of your universe that were previously invisible, visible to you. It also connects you to the people you’re there with. This is an essential quality of art—it is the way we connect with people we don’t know. It is a unique survival tool.

Lately you have been working on an impressive construction of your own—a 74,500-square-foot gallery on 25th Street in Chelsea. It looks a bit like a space station, or the kind of headquarters someone would use to conquer the world in a James Bond movie. What problem is this new space intended to solve?

The problem it’s going to solve is us having any liquidity! I don’t know if is going to solve anything, except that we’ve been in the same crappy space since I was five years old and I’m sick of it. But beyond that, what we are attempting to create is a gallery that’s highly transparent. There’s a library that’s open to the public, free outdoor spaces, and at the very top, there is an experience-performance space, which is about having the flexibility to do something that maybe we don’t exactly know what it is right now.

Most of all, it was supposed to finally solve the problem of the gallery being behind a velvet rope that only a few people knew they could pass. This is going to be an attempt to offer the artists some flexibility. We’re going to have beautiful painting shows in this space. We’re going to have beautiful sculpture shows in this space. But it will have the capability to do more.

A rendering of the façade of Pace’s new 25th Street gallery. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

The day before I toured your new gallery, I had the opportunity to preview MoMA’s new building, and what seems to unite the spaces—and also the Shed, about to open in Hudson Yards—is that each of these ambitious, next-generation art venues have adopted column-free spaces as their centerpieces for performances and other experiential art. It’s as if these art sites have been built with the expectation that some new kind of art is going come along and fill it. Meanwhile, you have a gallery like Hauser & Wirth’s 116,000-square-foot space in downtown L.A. that is based very explicitly on the museum model—there’s even an information desk, wall text, two gift stores, and a café. How do you think of your building as relating to a museum, or how is it different?

Our gallery doesn’t follow such a lifestyle model [as Hauser’s]. We have prioritized the spaces to be experimental in the way that they can be utilized by artists. You have to make choices even if you have 70,000 square feet.

But you know, for a long time you heard museums talk about how “the galleries are competing with us, they’re doing all these incredible exhibitions” and so forth. At this point, museums are more forward-looking than the galleries. They want to engage with a larger audience, and we’re stuck with this idea that we have this tiny audience that we are here to serve.

We [in the gallery sphere] have a kind of arbitrage-based art economy. It’s gotten to the point where we think that the value of an artwork comes from its last auction sale, which is not where the value comes from. So, if you’re going to build a new kind of gallery—if you’re going to build any new kind of system in the art world—it has to be pegged to the thing that represents the true value, which is what the artist created.

The new seventh-floor performance gallery, with steps that can function as a stage or seating. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

I have to ask, is there going to be a ticket booth somewhere in your new gallery? Will there be a ticketing component built in, like the kind you were experimenting with in Beijing and Palo Alto?

We are pondering. We’re trying to come up with an idea. It won’t necessarily be in this building, but if we think about it, if we listen to the artists, that model is going to grow wings, and it requires going beyond even something like our new gallery.

Right now, teamLab is building their own new 55,000-square-foot space in Brooklyn’s Industry City, with participation from Pace, that is going to be a gigantic kind of experiencatorium. Is that along the lines of what you’re thinking about for Pace?

We are thinking about it. It’s very important to me to think about those 799,000 people.

A cross-section view of the new Pace gallery. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

It seems to me like the art world today is going through a transformation not unlike the rise of the studio system in Hollywood, where the biggest, best-capitalized operations brought us the Golden Age of Hollywood cinema. How would you explain what’s happening in the art business now?

In the ‘90s and early 2000s, we were looking for disruption in the art world. The Internet has disrupted every other kind of retail business, so we figured it’s going to disrupt art too, and we saw artnet as a disruptor, we saw Artsy as a disrupter. They were never going to be the disruptors, no offense.

That’s because we are not a retail business, we are an experience business. We’re an experience business with the world’s most expensive gift shop. Art gets its value through experience. So Internet retail was never going to disrupt that—the disruption was always going to be through artists wanting to connect with other people.

All you have to do is look at the history of the music industry and read David Byrne’s brilliant book about it. The avant-garde disrupted the musical system and broke down the patronage system, and then technology came in and the music could suddenly connect directly to the general public: pop music, right? We haven’t really had pop art yet, and it’s coming.

Frederic Church’s Niagara. 1857. Oil on canvas, 1.01 x 2.29 m. Washington, National Gallery of Art (Corcoran Collection). (Photo by: Christophel Fine Art/UIG via Getty Images)

To return to the notion of ticketing, fractional ownership and subscription models have powered disruptive companies like Netflix, Spotify, and Airbnb. Tickets are one potential way of doing that in the art business, but it’s always been frowned upon. There are some exceptions, of course, like when the Hudson River School painter Fredrick Church debuted his painting of Niagara Falls as a one-painting gallery show in New York in 1857, and within two weeks of the opening, 100,000 people paid 25 cents to see it displayed in dramatic lighting. Why do you think ticketing has never caught on in galleries, even when works like Kusama’s “Infinity Rooms” and Christian Marclay’s The Clock draw hordes of visitors?

Okay, so the art object is a sacred object. Society lost religion in some ways, so the artists came in instead. There’s a whole economy based on these sacred objects. That becomes hard to disrupt.

These days, people are out there talking about fractional ownership of art, and blockchain—all of these ideas trying, on the one hand, to keep art this sacred thing, but on the other hand to highly commercialize it within a small group of ultra-wealthy people. The artists won’t stand for it. Big artists insist on meaning. And right now, for a lot of artists, that means reaching a much larger audience. It means de-commodification and democratization of art.

The disruption always at first looks like the art form is being debased. But we have to follow the artists, and if they want to go out and connect to a mass audience, that does not debase their work. If you try to create sacred objects and have them connect to a mass audience, that might be riskier in terms of debasing the work—just look at some of the stories of artists’ overproduction and so forth.

Random International’s Rain Room (2012). Photo: Felix Clay.

Disruption usually comes from the bottom up, but right now you see smaller galleries all over the world struggling with rising rents and at the same time needing to travel to art fairs all over the world because fewer people are actually coming into their expensive galleries to see sculptures and paintings. A lot of effort is being spent on figuring out how to maintain the brick-and-mortar gallery model, even as artists are starting to look to connect with this bigger audience. It seems that when disruption does occur, the biggest players will be perfectly poised to capitalize on it—but it could knock the smaller players out of the game.

You know, the art world is not fair. If you decide you want to be an artist, no one is going to be fair to you. You’ve made that crazy decision yourself. All of us who want to be in the art world, if we’re looking for fairness, look somewhere else—we don’t want everybody to have an equal crack at being a successful artist or a successful gallery. We have a very important nonprofit system in place, which I believe is essential to the ecosystem—that nonprofit system is there to give recognition to unheard voices. But if you are going to go out there and be a young gallery and you’re looking for social assistance to allow you to [succeed], I don’t think this is that kind of ecosystem.

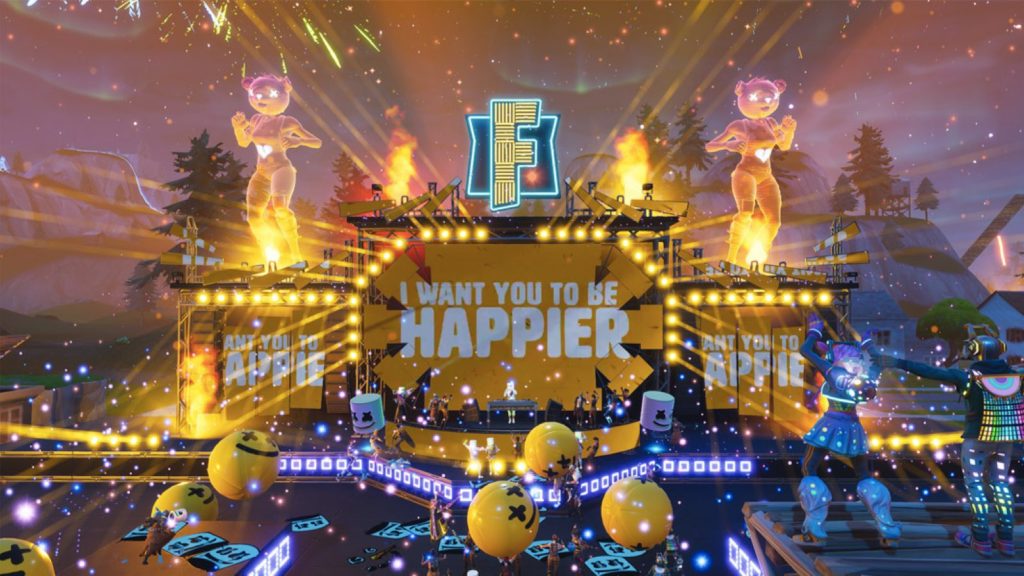

DJ Marshmello playing in Fortnite. Image courtesy of Fortnite.

We’ve been talking about the disruptive possibilities of immersive in-person experiences, but it’s interesting to point out that at the same time as Paramount has been disrupted by Netflix, Netflix is being disrupted by video games, which the company sees as a bigger threat than rival streaming services. Just a month ago, someone named DJ Marshmello played an in-game set in Fortnite that was attended by 10 million concurrent virtual concertgoers. When do you think these immersive art experiences that we’ve been talking about are going to be happening virtually?

When the virtual environment becomes one that’s truly not alone. Even though there were 10 million avatars there, the way they can experience each other is very rudimentary. A communal virtual world is some time away. Until then, it’s going to be very hard for the artist to live there. They’re certainly trying a lot of virtual reality, and developments are being made. But I think that it’s a tough environment.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics