At the Guggenheim, the Art Walked Beside You, Asking Questions

A few Saturdays ago, a teenage visitor to the Guggenheim Museum, a girl in a black beret, slid open the door to the Aye Simon Reading Room and peered in at a group of people in animated conversation. “Is there something going on in here?” she said.

A woman wearing red lipstick and Converse sneakers glared at her for a moment and turned away. “It’s a staff room,” a tall man in a plaid shirt said brusquely.

The girl in the beret backed up and slid the door closed. If she had been looking for art — there was none to be seen on the walls of the rotunda at the time — she had found it. But it was rather emphatically taking a break.

The men and women in the room were part of “This Progress,” a work by the British-German artist Tino Sehgal that took over the rotunda for the last six weeks. In the piece, which closed Wednesday, visitors were ushered up the spiral ramp by a series of guides — first a child, then a teenager, then an adult and finally an older person — who asked them questions related to the idea of progress.

Over the course of several hours-long shifts a week for the six-week run of the show, each of these guides, or “interpreters” as Mr. Sehgal calls them, spent a few minutes walking and talking with one or more visitors at a time, then moved on to the next. The show was extremely popular, with final ticket sales of more than 100,000, and on busy weekends a guide might interact with as many as 70 people in a day. By the time the guides retired to one of the break rooms — the reading room had been set aside for the teenagers and adults — they were taking refuge from encounters with the public.

Still, they were clearly invested in the spirit of the project. Mr. Sehgal, 34, is known for keeping a tight rein on every aspect of his work; he refused to divulge information about “This Progress” in advance, for example, and prohibited the taking of pictures. And his interpreters, although willing to allow a reporter into their midst while the show was on, were likewise reluctant to say much about it until it was over.

“It’s an elaborate social contract,” explained Ashton Applewhite, 57, a writer from Brooklyn who was one of the guides. “It would ruin something of the piece” for visitors to be exposed to its inner workings before they had experienced it themselves. As one of the teenagers put it, “What happened on the ramps stayed on the ramps.”

Speaking on Thursday, several of the more than 300 people who had been recruited for the show through e-mail messages and later in interviews (and in the case of the children, an elaborate series of auditions) confirmed that their starring roles in the season’s most talked-about artwork had been challenging, even trying at times. But most also seemed to have found the job and the wide-ranging and often philosophical dialogues it involved inspiring.

“This kind of conversation usually only happens when two people are drunk or something, or on the subway,” said Rafay Rashid, 20, a freshman at the State University of New York, Purchase. “There are great things in this world and one of them is talking to people, especially strangers. Rarely do you make eye contact with someone and try to figure out where they’re coming from.”

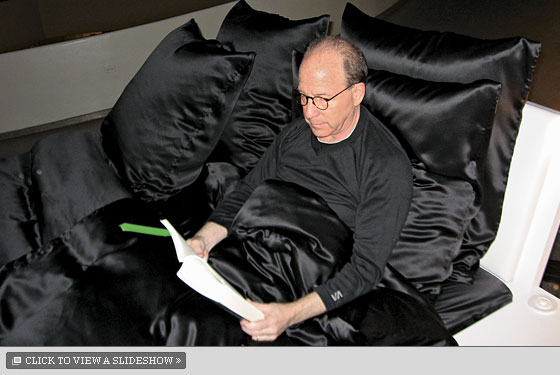

George Blecher, a 69-year-old writer and sometime actor, said he had not become one of those “who are ready to follow Tino around the earth” as a result of the experience, but he seemed to have gotten what he wanted from it.

“As you get older, your social life diminishes,” he said. “To a great extent older people really suffer from loneliness.”

At the same time, he added: “I ran out of steam after six weeks. You have to be alert and you’re giving so much.”

He was not alone. “After it was all over I had this image of all of us with these big metal windup keys in our backs,” Ms. Applewhite said. “How long would it take for us to all wind down?”

The schedule could be grueling even for much younger interpreters, who, unlike their elders, were unpaid. (They did receive a hat, bag and a museum membership; adults were paid $18.75 an hour, teenagers $7.25 an hour.) Solomon Dworkin, an 11-year-old sixth grader at the School at Columbia University who was one of the oldest children in the piece, said many of the younger ones had trouble with the pace of 40 to 50 interactions a day, 60 to 70 on weekends.

“They had a workload breakdown,” he said. “They would have liked more snacks.”

Some of the problem may have had to do with the intellectual rigors of the job. The younger children were “all pretty smart for their age,” he said, but “I’ve never met a 7-year-old who can match an 11-year-old in a conversation about philosophy.”

But even older interpreters found the pressure of nonstop thoughtful conversation draining. Bram Wasti, 16 and a junior at Hunter College High School, recalled that on his first day as a guide, one of the visitors had defined progress as “deprivatizing the Federal Reserve.” “I had absolutely no idea how to talk about it,” he said. (“I looked it up later, and it’s absolutely not true.”)

And Vinnie Wilhelm, a 31-year-old writer from Philadelphia, initially felt he needed to summon “the intellectual dexterity of Kant or Diogenes” to do the job, “as if you had to have these nuggets of intellectual insight so you could awe them with your oracular intelligence.”

Asad Raza, the producer of the exhibition and the recruiter of most of the guides, said he had seen the work improve over time, as the guides became more relaxed and more willing to be themselves. “There was a kind of anxiety about being chosen for their intelligence,” he said. It could lead to grandstanding. By the end, he said, the piece had become more personal.

Museum visitors, meanwhile, some of whom had no idea what to expect of the show, were not always relaxed about being approached by chatty strangers.

“I felt bad about it,” Mr. Rashid said. “You’d get rejected halfway up the ramp. They say something like ‘I think we’re here for the art.’ ”

The trick was not to take it personally. “If you get rejected it’s because they weren’t interested, not because you weren’t interesting,” he said, as if repeating a mantra.

And as in any service job, the customers could be difficult. At one point Betsy Carroll, 20, a junior at Columbia University, found herself refereeing a lovers’ quarrel. She had asked a couple “Do you learn from your mistakes?” The man said yes. His companion, a woman, rather vehemently disagreed.

“She had a lot of anger about that,” Ms. Carroll recalled. “She chose this moment to bring it up.”

Daniel Kaiser, 73, a literature professor at Sarah Lawrence, noted that “European and Asiatic couples are very polite — they listen to what you say.” American college students, on the other hand, “are the worst — they have bad manners.”

In the reading room where the adults gathered, a joke circulated in which a guide pushes a particularly annoying visitor over the edge of the ramp rail. Gesturing toward the body below, the guide would announce the title of the new work: “Tino Sehgal, ‘This Pancake,’ 2010.”

But even those who found the gig trying seemed generally happy with their experience, and hopeful about sustaining some of the connections they had made. “One of the things I’m anticipating is that someone will come up to me in a coffee shop and say ‘Hey, I talked to you at the Guggenheim,’ ” Mr. Blecher said.

In the final days of the show, feeling ill, he took a taxi home after his last shift. He began talking to the cab driver, a New Yorker of 31 years. “ ‘I love to have these interesting conversations,’ ” said the driver. “I’ve been practicing a lot,” Mr. Blecher replied.

An article last Saturday about people who acted as guides as part of the work “This Progress” by Tino Seghal at the Guggenheim Museum misstated the surname of one and misspelled the given name of another. A sixth-grader at the School at Columbia University who took part is Solomon Dworkin, not Bender. A junior at Hunter College High School who also served as a guide is Bram Wasti, not Bran.

How we handle corrections