| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

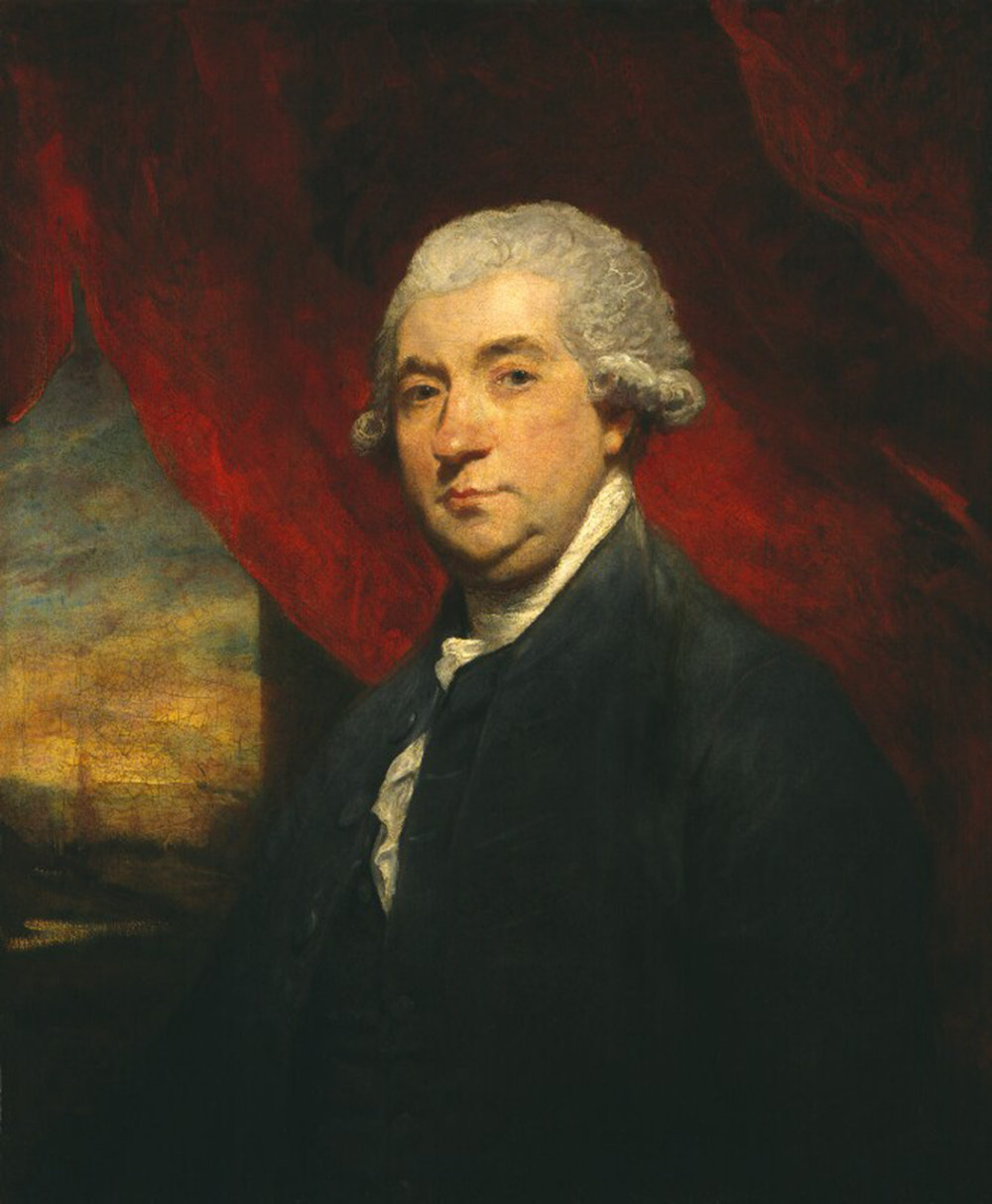

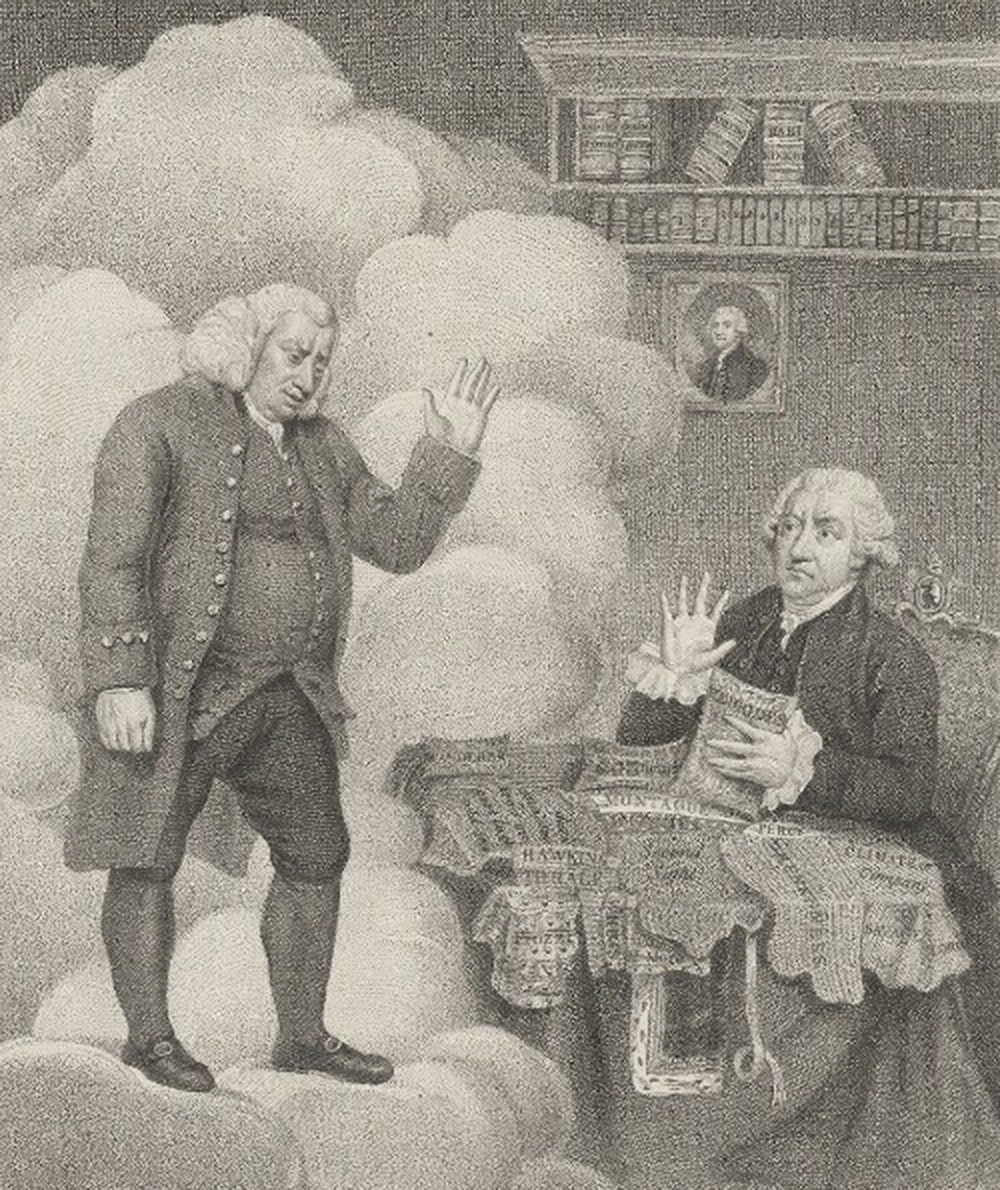

We know little about Samuel Johnson’s inner life when he was in his early twenties. About James Boswell’s we know a very great deal, because he was deeply interested in it himself, and because he now began to write about it nearly every day. He had experimented with keeping a journal earlier, which was by no means a common practice. There did exist a tradition of journals with a religious theme, but few straightforward records of everyday experience. Samuel Pepys’ diary is an obvious exception, but although written in the 1660s, it wasn’t published until its cryptic code was cracked in the nineteenth century. The journal Boswell kept in London in 1762-63 covered eight months and filled seven hundred manuscript pages, with extraordinary richness of detail.

The story has often been told how Boswell’s papers were believed to be lost until they unexpectedly turned up, in the early twentieth century, in a castle in Ireland where descendants of his were living. A wealthy American collector talked the owners into selling him the entire mass of material, though not before they had torn out whole swatches that they considered embarrassing. He in turn sold them to Yale University, and ever since then they have been receiving expert editorial attention in what became known as the Boswell factory. Reviewing one volume in the series forty years ago, John Updike said, “The expenditure of human time and intelligence has been on the scale of Talmudic commentary.”

The first volume (by now there are thirteen) was published in 1951 as Boswell’s London Journal, edited by Frederick Pottle, who was the head of the factory and would later publish an engrossing biography of Boswell. It was at the top of the New York Times bestseller list for a couple of months, was offered as a dividend by the Book of the Month Club, and was the subject of a feature article in Life magazine entitled meet mr. boswell. he is fun to know, and he is good for what ails us now. What made him good for Americans in 1951 was his “sunny world, all laced coats and powdered hair,” comforting when everyone was dreading the hydrogen bomb. President Truman took the book with him as vacation reading. Above all, though, it was popular because it was astonishingly frank about sex.

An important purpose of the journal was simply to produce an ongoing record of life as Boswell lived it: “In this way I shall preserve many things that would otherwise be lost in oblivion.” During a period when he was confined by illness he lamented, “What will now become of my journal for some time? It must be a barren desert, a mere blank.” And a couple of weeks later, “Nothing worth putting into my journal occurred this day. It passed away imperceptibly, like the whole life of many a human existence.” On the other hand, it was easy to feel that the thing was becoming a burden—“my lagging journal, which, like a stone to be rolled up the hill, must be kept constantly going.” But not bothering to write things down was distressing too. “I am fallen sadly behind in my journal,” he later wrote; “I should live no more than I can record, as one should not have more corn growing than one can get in.”

In hindsight we can see what Boswell couldn’t yet know, that in writing the journal he had found his true vocation, in the old sense of a calling. A career is a climb up the ladder of success, and he was reluctantly accepting the law as his career. He would never get further than a couple rungs up that ladder. A vocation is chosen for its own sake. He once commented that for him, writing and drinking were both addictive. “One goes on imperceptibly, without knowing where to stop.”

Of crucial importance was the commitment to veracity that Boswell said his father had thrashed into him. All his life he wrote down notes, if not full narratives, as soon after an event as possible. Otherwise, “one may gradually recede from the fact till all is fiction.” A modern critic has coined a term for the result: “the fact imagined.” In an early journal Boswell found an apt metaphor for the telling details he wanted to preserve: “In description we omit insensibly many little touches which give life to objects. With how small a speck does a painter give life to an eye!”

What Boswell wanted above all was to establish a consistent character, reliably the same at all times, and to be admired for his stability. “I have discovered,” he wrote hopefully soon after arriving in London, “that we may have in some degree whatever character we choose.” But as he had to admit a few years later, “I am truly a composition of many opposite qualities.” Pottle calls him “an unfinished soul.”

One problem was that Boswell could never resist being the life of the party, inviting companions to laugh at him as much as with him. “I was, in short, a character very different from what God intended me and I myself chose.” If only he could be certain what God meant him to be, and then be it!

Settling down in London, he took a stab at defining what his ideal character might be.

Now, when my father at last put me into an independent situation, I felt my mind regain its native dignity. I felt strong dispositions to be a Mr. Addison. Indeed, I had accustomed myself so much to laugh at everything that it required time to render my imagination solid, and give me just notions of real life and of religion. But I hoped by degrees to attain some degree of propriety. Mr. Addison’s character and sentiment, mixed with a little of the gaiety of Sir Richard Steele and the manner of Mr. Digges, were the ideas which I aim to realize [i.e., make real].

This is touchingly earnest, and touchingly confused. “Native dignity” was just what Boswell never had. All his life he would keep reminding himself in vain to be retenu—restrained and reserved. And what a curious set of role models! Collectively Joseph Addison and Richard Steelewere “Mr. Spectator,” an amused, detached persona very different from the authors themselves. Steele was gregarious, had been a cavalry officer, and had fought duels. The real-life Mr. Addison was pathologically recessive and wrote in the very first Spectator, “The greatest pain I can suffer is being talked to, and being stared at.” Boswell liked nothing better than being talked to and stared at.

As for West Digges, that was the dashing actor he had known in Edinburgh, irresistible to women and the embodiment of the romantic highwayman Macheath in The Beggar’s Opera. Boswell was often inclined to identify with Macheath. Rather than thinking in terms of character, what Boswell really needed was a concept of personality, which no one had formulated yet. In Johnson’s Dictionary “personality” means merely “the existence or individuality of anyone,” that is, one individual person as distinguished from another, not a cluster of unique characteristics. A character was expected to be consistent; a personality may seem startlingly inconsistent, and yet have a deeper unity underneath the contradictions. Boswell sensed that in himself but didn’t know how to articulate it.

At this time in Western culture, a major divergence in styles of self-presentation was much in the foreground. To adopt a contrast from classical rhetoric, it was a struggle between homo seriosus and homo rhetoricus. Serious man—and serious woman—has a core of authentic self and uses language to communicate truth. Rhetorical man exists in society, takes coloration from it, and knows who he or she is not by introspection but by feedback from other people. Language becomes a game, playfully exploited to entertain or persuade, but not to express a “truth” that may not even exist.

Boswell wanted very much to believe in an authentic core of self. Yet he was freest, happiest, and in a real sense most fully himself when he was performing and improvising.

We don’t know when Boswell first read David Hume’s 1739 Treatise of Human Nature, but since he had been taught by Hume’s close friend Adam Smith, he may well have picked up something about it by this time. In a section titled “Of Personal Identity,” Hume declares that the only consciousness of our selves we can ever have is of the stream of sense impressions that the mind processes from moment to moment. “When I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception.”

Something must organize those impressions, no doubt, but Hume acknowledged frankly that he had no idea what it might be. It follows that a person is “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.” In one of his later journals Boswell said the same thing: “Man’s continuation of existence is a flux of ideas in the same body, like the flux of a river in the same channel.” That certainly sounds like homo rhetoricus.

Hume drew a further conclusion. Attempting to know the self through introspection is not only fruitless, but may lead to alarming anxieties. The solution is to stop trying.

I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther. Here then I find myself absolutely and necessarily determined to live, and talk, and act like other people in the common affairs of life.

One of Hume’s critics objected sarcastically that in that case, “a succession of ideas and impressions may eat, and drink, and be merry.” Hume, who loved to eat and drink, would have seen nothing wrong with that. We may not know the meaning of life, but we do know how to live it.

There is still another way in which Hume’s view of experience would be attractive to Boswell. Johnson’s Rambler essays are full of warnings against yielding to emotion, together with injunctions to keep “reason” firmly in command. Hume’s Treatise was a head-on challenge to that kind of ethical psychology: “Reason is, and ought to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to be any other office than to serve and obey them.” As a young man Hume had been raised, like Boswell, in a stern Presbyterian faith, but he became a skeptical agnostic and virtually an atheist.

By “passion” Hume and others were beginning to mean what they called “feeling” and we would call “emotion”: instinctual responses to the demands of living. In effect passion was being decriminalized and made a constructive part of existence.

Still, if Hume’s account of the self might have made a lot of sense to Boswell, there are aspects of it that would not. It was no problem for Hume to let reason be the slave of the passions, because his own passions were mild. He said so himself, in a little sketch called “My Own Life” written when he knew he was dying of cancer. “I was, I say, a man of mild dispositions, of command of temper, of an open, social, and cheerful humour, capable of attachment but little susceptible of enmity, and of great moderation in all my passions.” Boswell’s passions were greatly immoderate.

Hume liked to take a social glass; Boswell got drunk—in later years appallingly drunk. Hume seems to have had little if any sex life; Boswell compulsively picked up prostitutes and felt bad about it afterward. He needed something more than Hume’s flux: he needed to construct a stable character on the Johnsonian model. Soon he would encounter Johnson in person, and would enlist him as a mentor.

It seems clear from Boswell’s journals that he felt most alive—most himself—when he was simply relishing the present moment, not trying to understand or explain it. One such experience occurs during a chilly December evening, and we need to remember how bitterly cold it could be in London when the temperature indoors was much the same as outdoors. “It is inconceivable with what attention and spirit I manage all my concerns. I sat in all the evening calm and indulgent. I had a fire in both my rooms abovestairs. I drank tea by myself for a long time. I had my feet washed with milk-warm water, I had my bed warmed, and went to sleep soft and contented.” Not just one fire, when coal was expensive, but two. Not just warm water, but “milk-warm water,” as if fresh from the cow. And finally, the sensual delight of feeling “soft and contented.” That is what Rousseau would soon theorize as le sentiment de l’existence, the sensation of simply being, complete in the moment.

Excerpted from The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age, by Leo Damrosch, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Leo Damrosch. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.