SAVING FACE art theory by Jorge Cardoso (part 2)

[to be continued]

|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Lisa Sorgini ©

Federica Belli The language of photography is still among the most contemporary ones, despite the growing diffusion of other digital arts. Which makes photography particularly exciting in our time?

Antonio Carloni Actually, photography is the easiest language to understand due to its intrinsic realism. As soon as Steve Jobs revolutionised our life by putting Apple devices in our hands every day, photography has become the main language through which we communicate, with text becoming a secondary language. Images have become the most immediate and popular medium to communicate with friends as well. Photography can be divided in two layers: the most diffused is its daily usage, the communicative kind of images which are spread by the majority of the population, then there is authorial photography, which is used professionally and artistically.

F.B. The technological revolution linked to the evolution phones is actually not considered enough in the spread of photography: probably more than the spread of professional cameras, our daily digital communication has led to a viral approach to photography. Your new role of Deputy Director Gallerie D'Italia in Piazza San Carlo implies planning and managing exhibitions proposing professional photography to a public used to daily photography. Which criteria do you evaluate as most important when choosing the themes of upcoming exhibitions?

A.C. First of all, the vision of Gallerie d’Italia is the vision of a private and bank-owned museum. That implies that the main topics regard our upcoming future: climate change, poverty, inclusion and other social issues. The central concern for the museum regards the nature of the life of our children, the situation humans will have to face in the upcoming 25 years. To discuss such concern, we commission the creation of visual stories to great photographers, connecting the policies of Intesa Sanpaolo and the interests of our public. Such approach is quite new in the scene, as until now museums have been either private or public, having in the latter case a curator who chooses the program of the museum. Here, on the other hand, we will plan a series of exhibitions in which each curator works alongside a photographer for a single project. The outcome would be a general overview of the state of things in our time.

Martin Weber ©

F.B. It sounds like Gallerie d’Italia is trying to fill a gap, bringing together the strengths of a public institution and the ones of a private museum. Such approach is quite different than the one followed by the Director of a photography Festival. In which ways does the selection of projects change when planning a photography festival such as Cortona on the Move as opposed to the one required by a museum like Gallerie d’Italia?

A.C. In Cortona I used to rely on a curator who selected most of the content to be featured. She chose the theme of the yearly festival and then proceeded to bring together the content for the exhibitions. The best feature of a festival is the freedom to expose photographs as one desires and to involve the people one trusts the most. On the other hand, building the program for a private museum implies balancing the culture built in the structure of the institution and the cultural stimuli coming from outside. The program has to satisfy both inputs, and that is the main challenge I am currently facing.

F.B. Such project is quite ambitious and it will probably evolve and adapt as the museum opens its doors and receives the first feedbacks. Talking of feedbacks, as former Director of the Cortona on the Move Festival, you gave life to a gathering that over the course of ten years has become one of the most respected in Italy. At which point did you realise the impact of the event you were creating?

A.C. Actually, I only realised what I had built when I was about to leave. As I started to work on the first projects, trying to understand how to involve the people around me in my new endeavour and at the same time taking some distance from the reality of Cortona where I had been working, allowed me to understand the importance of the festival – first of all for the simple fact of bringing together a community who shares the love for photography, but mostly for organising such a gathering in a small and isolated village as Cortona is. Thus, as I started calling around to propose collaborations for my new projects here and I introduced myself as the former Director of Cortona on the Move, I noticed how mentioning the festival helped in making people eager to work on something with me.

Gregory Crewdson ©

F.B. After all, this is often the case: as soon as we realise we are about to leave something we start to realise its value. And not only that, the community feedback is fundamental to realise the state of things. The focus of the new museum will be specifically photography. In which ways is the specificity of the language influencing the exhibition planning and the communication with the public?

A.C. When opening a museum, the relationship with the public is always one of the most important aspects to consider, independently of the language exhibited. My goal is to mix the themes the bank is concerned with and the needs of a public living in our days. In addition to that, this museum has to reach a point in which it is really perceived as something new in the Italian art scene, both due to its focus on photography and due to the twofold nature of its mission.

Photo Editing by Lenin Arache

Every work of art tells a story, but what of the stories inspired by art? Art has fired the imagination of literary giants such as Émile Zola, Marcel Proust and Virginia Woolf. Entire novels have emerged from single paintings—think Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch (2013)—while others have revisited chapters of art history, such as My Name is Red (1998) by Orhan Pamuk. Art can be a hook and a visual cue, a window into another time and place. Here are five of the best recently published art-inspired novels.

Seasonal Quartet (2017-20) by Ali Smith

They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but the David Hockney paintings that envelop each instalment in this remarkable series give you a good glimpse of the content. Ali Smith is no stranger to marrying art and fiction—her two-part novel How to be Both (2014) was inspired by an allegorical fresco by Francesco del Cossa—and these up-to-date tales, set against a fraught political backdrop, highlight the creations of Pauline Boty, Barbara Hepworth, Tacita Dean and others.

Painting Time (2021) by Maylis de Kerangal

Maylis de Kerangal’s engaging new novel, translated from French, explores the well-travelled but always surprising territory between appearance and reality. It follows Paula through her studies at the Institut Supérieur de Peinture in Brussels—where she is learning the art of trompe l’oeil—and a string of decorative painting jobs in France and Italy. An expert at imitating wood, marble and semi-precious stones, Paula is, in her own words, part of a gang of copyists, “bamboozlers of the real, traffickers of fiction”.

Second Place (2021) by Rachel Cusk

Rachel Cusk’s latest book is a loose fictional retelling of Lorenzo in Taos, a 1932 memoir by the American socialite and patron of the arts Mabel Dodge Luhan. It charts the relationship between an introspective woman writer we know only as M and an irascible male artist called L, who sparks within her a desire for artistic self-expression—“a dangerous part of me, the part that felt that I hadn’t truly lived”. A thought-provoking meditation on the power of art and who is lucky enough to make it.

Portrait of an Unknown Lady (2022) by María Gainza (translated by Thomas Bunstead)

María Gainza’s follow-up to her richly detailed debut, Optic Nerve (2019), poses questions about the nature of originality and makes a case for the oft-quoted epithet attributed to Pablo Picasso: “Good artists copy, great artists steal”. Set in the Buenos Aires art world, it follows an unnamed young woman who gets a job in an auction house and becomes obsessed with finding a legendary art forger called Renée.

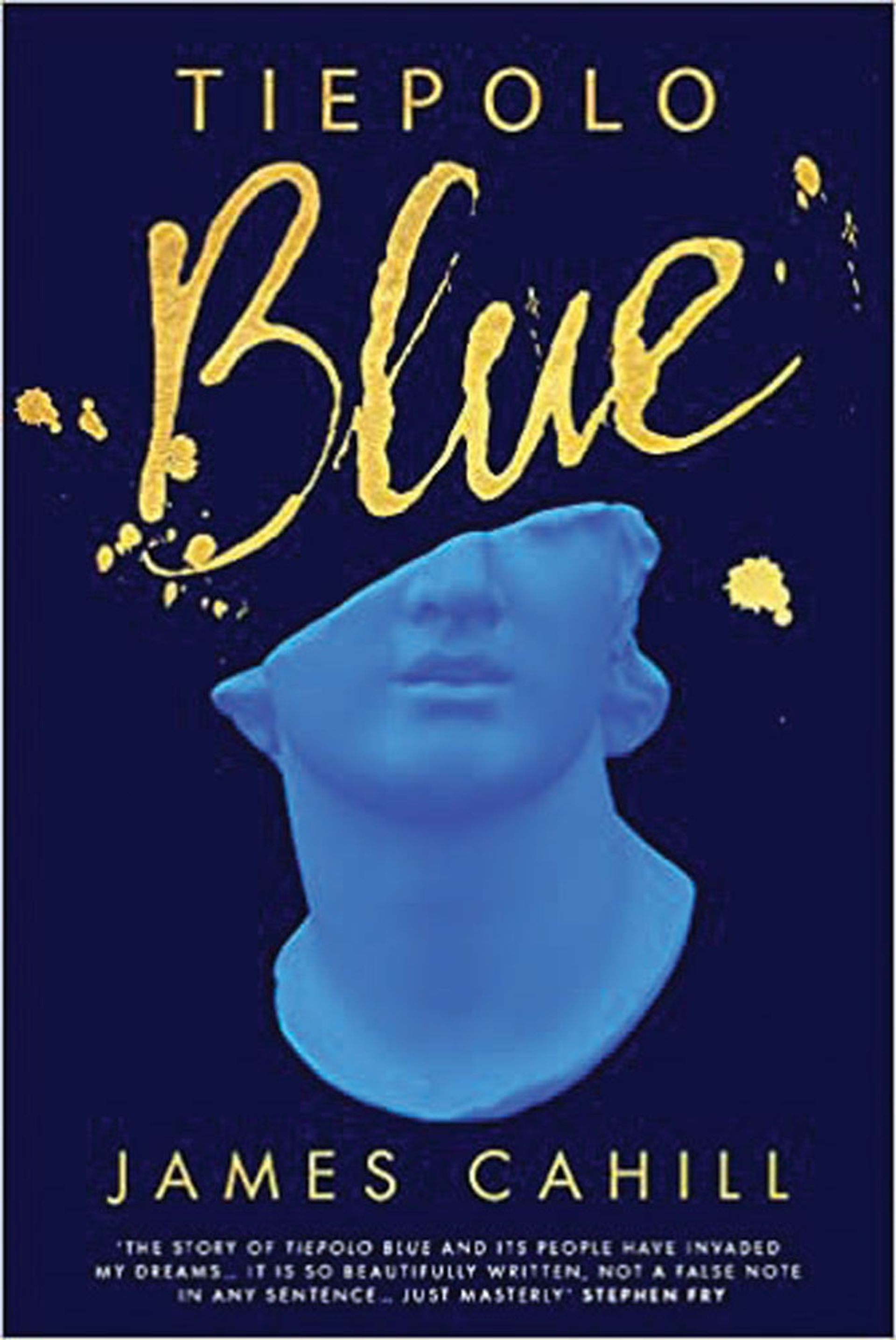

Tiepolo Blue (2022) by James Cahill

“The idea of what art is—or what it could be—is there all the way through,” says James Cahill of his forthcoming debut novel. Tiepolo Blue brings together the classical forms of the Italian masters and the anarchic found objects of the YBAs. An absorbing coming-of-age story that charts the artistic and sexual awakening of a Cambridge professor in 1990s London.

• Chloë Ashby is the author of Wet Paint—another novel inspired by art—which is published this month by Trapeze