Visual Culture

How White House Photographers Have Shaped the Image of the President

President John F. Kennedy walks with his son along the West Wing Colonnade of the White House, 19. Photo by Robert Knudsen. Courtesy of White House Photographs and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

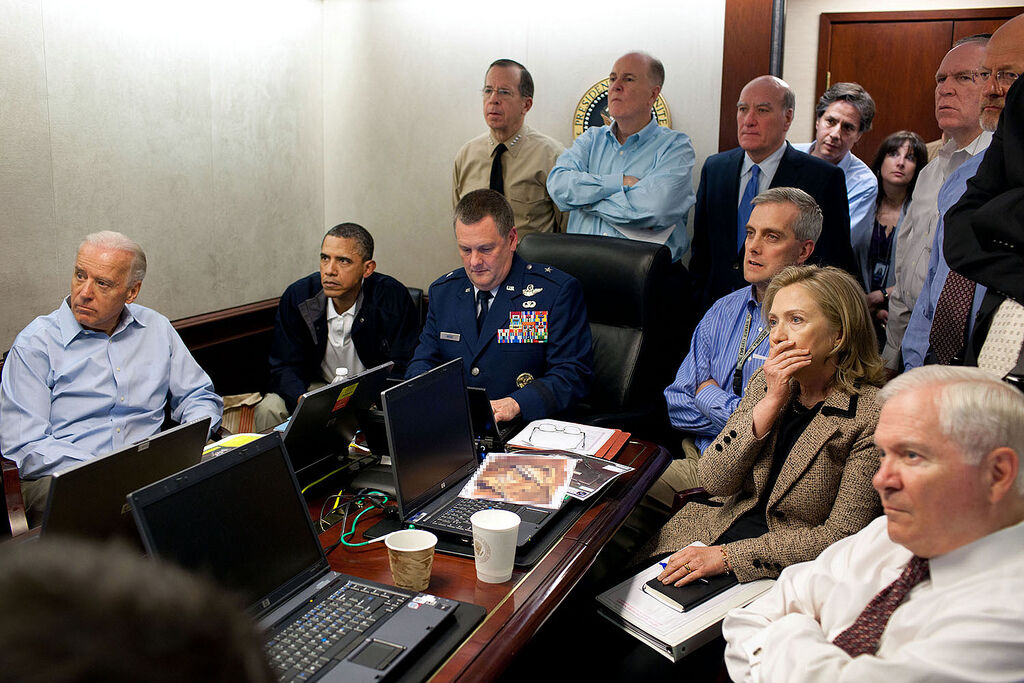

When you picture past presidents of the United States, whom do you see? Perhaps you envision John F. Kennedy as a doting father, playing with his children in the West Wing. Maybe you remember Richard Nixon as the smiling yet stiff leader who posed hand-in-hand with Elvis Presley in the Oval Office. In the case of Barack Obama, you might recall him as the solemn-faced Commander in Chief, watching the Osama bin Laden raid in the Situation Room, or as the first African-American president, bowing his head so that a 5-year-old black boy could compare their haircuts. Official White House photographers—the image-makers who quietly author visual archives of America’s Commanders in Chief—craft these impressions, which become indelible in the public imagination.

Prior to Kennedy’s presidency in 1961, the role of official White House photographer did not exist; instead, various military photographers captured events such as state dinners and overseas visits. As journalist Kenneth T. Walsh observes in his 2017 book Ultimate Insiders: White House Photographers and How They Shape History, Kennedy “understood the importance of image,” and chose Cecil Stoughton, a U.S. Army Signal Corps photographer, to document his presidency.

Swearing in of Lyndon B. Johnson as President, 1963. Photo by Cecil Stoughton. Courtesy of the White House Photo Office.

Stoughton established a new normal through his access to Kennedy, offering the public the first personal view of a sitting president’s life. But Stoughton also reported to Kennedy, who limited the circumstances in which he could be photographed, and controlled which images could be made public. “The Kennedys imposed restrictions to protect their image as an elegant, graceful couple,” notes Walsh. Photographing the president entering a pool, for example, was off-limits until “he was submerged to the neck,” so as to not reveal his back brace.

Stoughton’s body of work—which primarily exudes youth, glamour, and a happy First Family—contributed to the “Camelot” mythology built in great part by First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. One of the most essential occasions Stoughton captured took place only hours after Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, when Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson took the oath of office on Air Force One after leaving the hospital where Kennedy was pronounced dead. The gravity of the moment is palpable: Johnson is pictured, hand raised, with Jacqueline Kennedy to his left (the blood stains on her clothing are out of sight) and Lady Bird Johnson to his right. Stoughton, due to his proximity to the presidency, was able to document this peaceful transition of power, executed quickly in a moment of tragedy—showing America what otherwise would have only been heard through audio.

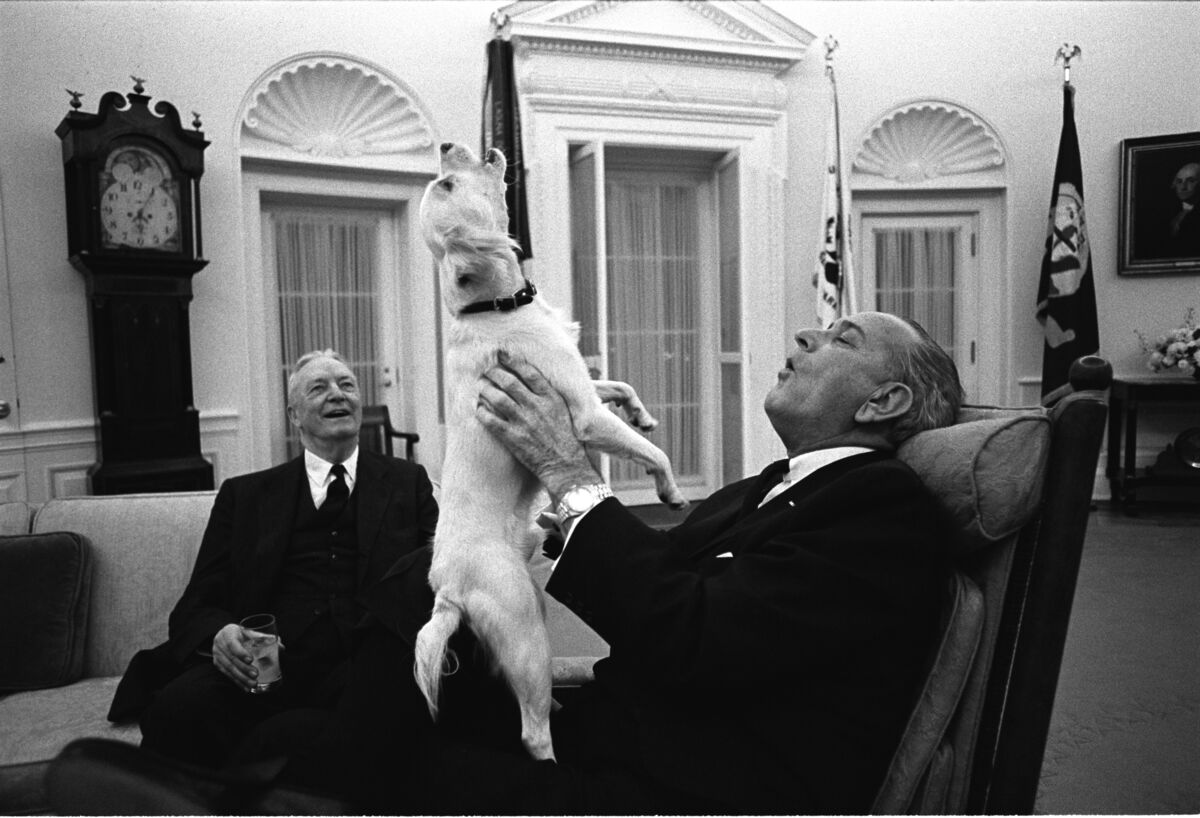

President Lyndon B. Johnson sings with Yuki as Ambassador David Bruce looks on, 1968. Photo by Yoichi Okamoto. Courtesy of the White House Photo Office.

After taking office, Johnson altered the course of White House photography by allowing expansive access to his appointee, Yoichi Okamoto, whom Johnson worked with as vice president. Okamoto captured Johnson happily howling with his dog; in historic meetings with Civil Rights leaders; recovering from surgery in bed, on an IV drip; and, of course, giving the “Johnson Treatment,” which involved the president imposing his physical stature upon politicians in his path. The effect of these images is that of a fly on the wall, a public eye placed in the room with one of the most powerful men on earth.

“I had always looked to Yoichi Okamoto…as the level of access that I wanted to attain,” Pete Souza, chief official White House photographer to Barack Obama, told Artsy. Souza, who previously photographed for theChicago Tribune, documented Obama’s rise from freshman senator in 2005 to the presidency in 2009. He describes Obama as “someone who understood the value of a visual historical record of his administration,” and Souza, in turn, was given broad access—including top security clearance—to the Commander in Chief throughout his tenure.

“I saw my role as someone trying to create an archive of photographs for history; that was the number one thing in my mind,” said Souza.“Everything else didn’t matter as much to me. What mattered is that I was doing a service to the future, really, to have this archive that will live in perpetuity.”

President Barack Obama bends over so the son of a White House staff member can pat his head during a family visit to the Oval Office, 2009. Photo by Pete Souza. Courtesy of the White House Photo Office via Flickr.

The National Archive preserves the nearly 2 million images that Souza captured during the Obama years, along with the work of previous official White House photographers—though each leader’s presidential library also has a role in their management, and not all pictures are made public. The Obama administration was the first to use its own website and social media platforms, such as Flickr and Instagram, to consistently release photographs. (For context, according to Mike Davis, an in-house picture editor for George W. Bush, usually one or two photos of the president were released per week to the press, in addition to special requests.)

But the climate for publishing images has changed considerably over the decades. Souza first served as a White House photographer during Reagan’s presidency from 1983 to 1989, when the approach to publishing images was more cautious. “This was in a day where there was no such thing as the internet or social media, and if a picture was going to be released, they knew that it would likely be used by ABC, CBS, NBC, and they were just really careful about what was released because those three networks had such power,” said Souza. “I think they were a little bit more in control of the image.”

10 Images

View Slideshow

Under the Obama administration, Souza said, he ultimately had the final choice of which images were made public, so long as they didn’t contain sensitive material. His prolific output and unfettered access did come with criticism, however: The Obama administration limited press photographers’ access to some events; instead, they released Souza’s images, which the White House News Photographers Association likened to handing out a “visual press release.” In November 2013, the White House’s then–deputy spokesman Josh Earnest responded, in part: “We’ve taken advantage of new technology to give the American public even greater access to behind-the-scenes footage or photographs of the president doing his job.”

President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, along with members of the national security team, receive an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden in the Situation Room of the White House, 2011. Photo by Pete Souza. Courtesy of the White House Photo Office via Flickr.

“Everybody is trying to come to terms with the impact of social media,” said

, Gerald Ford’s official photographer, to the New York Times. “I don’t know what the right balance is, but I understand [Souza’s] position in terms of the historical record.” Internally and externally captured imagery both have roles in understanding a presidency, as has been made apparent once more during the current Trump administration.

Shealah Craighead, who currently holds the role of chief official White House photographer, has approached the role quite differently from her prolific predecessor. She previously served as personal photographer to Laura Bush, in addition to working for Sarah Palin and Marco Rubio, and was hired soon after documenting Trump’s inauguration. As Ian Crouch observed in The New Yorker in March 2017: “Trump is the most radically accessible President in American history: we have, via Twitter, a direct connection to what seems to be the animal portions of his brain. Yet, in the first months of his Presidency, the Trump we’ve seen in images is almost exclusively the official, public-facing Trump, and his Administration’s use of photography has been much more limited than that of his immediate predecessor.”

Compared to the Obama administration, Trump’s team has released fewer photographs—and, more notably, less intimate ones—via sites like Flickr. Craighead’s images are often rigid, and say little of Trump the man. (Souza will not comment on the current administration’s approach to the role, but through social media and his latest photo book Shade: A Tale of Two Presidents, he uses images of Obama to criticize President Trump.)

President Donald J. Trump waves to awaiting supporters, 2018. Photo by Shealah Craighead. Courtesy of the White House Photo Office via Flickr.

Craighead, when asked by PBS NewsHour in August 2017 about her level of access to the president, said, in part: “There’s a level of trust we have to establish with each other. That, in time, will unfold into a level of comfort and access.”

Nixon famously restricted the access of his photographer, Ollie Atkins, and Jimmy Carter is the only president to have not hired an official White House photographer since the role’s inception. In both cases, as with Trump thus far, the public lost an opportunity to better understand its leader beyond cliché political photo ops like the “grip and grin” handshake. One hopes that Craighead has more unreserved access than it appears, so that one day, the public can see close-up images of how this wholly unconventional administration has been run. As Souza noted of his time in the White House, acting as a constant shadow allowed him to capture the “the small moments” of Obama’s presidency, and those images often say the most about the subject: “To me, those are more revealing and more important, especially if you’re looking at pictures in 50 or 100 years, to determine: What kind of person was this guy?”

Haley Weiss