| ||||||||||

|

|

|

GUIDE

How to take better photos

Anyone can learn the principles that are essential to capturing quality images. Follow these tips and see the difference

by Paul Pope

Photo by Psyche. All other photos supplied by the author

Need to know

A selfie-taker caught my attention at a wedding once: they kept returning to an inflatable castle to get a picture of themselves with some guests playing in the background. They didn’t stop before to-ing and fro-ing five times – presumably, the first four attempts weren’t good enough, but the fifth one was a winner. Sound familiar? Smartphones and digital cameras make it easier than ever to take and share photos (and to save numerous versions to choose from), but many of us still aspire to capture the perfect image of a memorable moment, person or place. While just about anyone can take a picture, perhaps you’d like to take more photographs that truly capture the richness of an experience, or that other people will appreciate, or that will push the boundaries of your creativity.

Before the era of social networking sites, creating and sharing photographs was more deliberate and less instantaneous, which made picture-taking feel special. Families cherished the physical print – a link to the past with sentimental value – and kept their precious memories in albums, rarely showing them outside the family. Today, people commonly take photos not only to serve as memory cues but to tell others who they are, what they care about, and how they feel. The functions of photography have expanded to include connecting socially and helping to define one’s identity. Photography is also a way to express creativity and to document the beauty, diversity and uniqueness of different places, cultures and people.

In this Guide, I will provide some photographic principles and specific tips for casual, amateur and aspiring photographers on how to take better photos. By ‘better photos’, I mean appealing images that evoke emotions in the viewer and capture the essence of a subject or scene (and that resonate with how our brains make sense of the world).

Whatever your intentions when you take photos, aiming to capture better ones can bring many benefits. Photography is a relaxing hobby, one that can get you outdoors and provide a break from the stresses of daily life. It can increase the enjoyment of experiences, and lead to creative fulfilment – boosting your confidence and self-esteem as you chronicle special occasions for the future. And, the act of looking back at these pictures can make you happier. Practising better picture-taking also helps people who aspire to take pictures for professional reasons, of course: a portfolio of eye-catching images can help attract clients, engage audiences, promote products and services, and raise awareness of social causes.

What makes a good photo?

It’s not always easy to judge the superiority of one image over another. The American photographer William Eggleston has a personal discipline for only taking one photo of a thing. Not two! Why? Because he would have trouble deciding which one was better. It’s even harder to figure out which photos other people will appreciate the most. I like Eggleston’s mundane photos, but others find his work boring. A picture-viewer’s personal experiences can influence their aesthetic evaluations beyond the work’s composition and subject matter.

That being said, there are several key concepts we’ll cover in this Guide that can help you improve your picture-taking:

Composition – this is the way you arrange visual elements within the frame, guiding the viewer to the main subject or theme and helping you to create visually pleasing and balanced images.

Storytelling – in photography, this involves using an image (or multiple images) to engage viewers emotionally or intellectually, helping them to understand why you took the photo. A story connects people with the photo’s subject or theme, making your images memorable.

Join 84,000+ weekly newsletter subscribers

Intriguing articles, practical know-how and immersive films, straight to your inbox every Friday. Our content is 100 per cent free and you can unsubscribe anytime.

Empathy – by which I mean connecting with and trying to understand the subject to help you create more authentic and emotionally resonant images (capturing, for example, people’s expressions or the mood of a landscape).

My guidance will draw from the practices of accomplished photographers who are renowned for their mastery of composition, storytelling and empathy. It will also rely on insights from psychology, which provide a scientific basis for understanding the value of those three, interrelated elements of successful photography. Indeed, my expertise in teaching psychology has helped me to create images with impact as a professional photographer for the past 20 years. Learning from those who know the winning formula can help you take better photos yourself, even if you’re thinking more deliberately about your photography for the first time.

What to do

A quick note about your camera: does it matter what kind you use? Smartphones are convenient and portable, making them great for capturing moments spontaneously. For greater control over the shots, digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras offer a range of interchangeable lenses and allow for high-quality images. Lastly, traditional film cameras provide a unique aesthetic quality and promote a thoughtful approach to photography, because film rolls have a finite number of exposures. (I shot the images in Figures 2, 4 and 5 below using 35mm film.) Film cameras also help you live in the moment when taking photos, since you can’t instantly review and delete shots.

Ultimately, the best camera is the one that suits your needs, preferences and imagination. And, while the choice of camera and other tools (such as photo-editing software) makes a difference, they are secondary to your skills, creativity and intent. Your eye and creative vision will make a picture compelling.

Aim for a balanced composition

Experts agree that well-balanced compositions help to create visually engaging pictures. (Images with more balance even receive more Instagram Likes – one proxy for aesthetic appeal.) Achieving pictorial balance does not always come naturally to non-professional photographers, but beginners can learn to improve their compositional skills. What follows are some specific tips for doing so, using either of two strategies: symmetrical balance or asymmetrical balance.

Achieving symmetrical balance

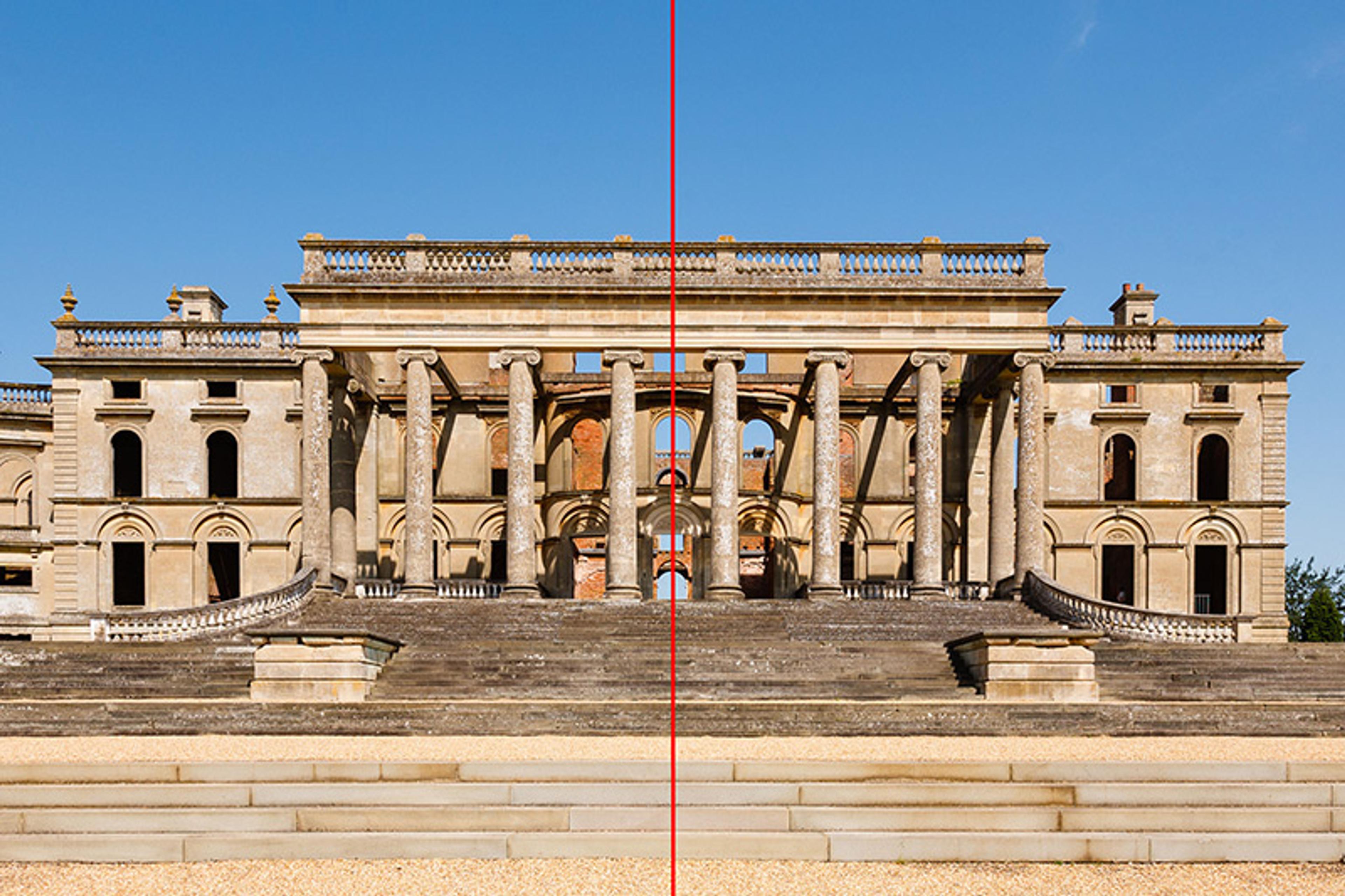

The simplest way to achieve balance in your photo is by arranging it so that visual elements on both sides of the frame mirror each other. This strategy creates a well-balanced composition through symmetrical or ‘formal’ balance (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Here’s how to do it:

- Select a suitable focal point: look for subjects or scenes with clear lines or shapes that have visual elements suitable for a symmetrical image – such as a striking architectural feature with similar (if not identical) left and right halves.

- Centre your subject: position your camera so that your subject is in the centre of the frame. This simple but classic approach allows elements to mirror each other from left to right, top to bottom, or around the centre of the image.

- Check alignment and framing: pay attention to vertical and horizontal lines, such as the outer edges of the building in Figure 1. Try to ensure that these lines are parallel to the edges of the frame. (If you eventually edit the photo using software, steps such as cropping and straightening can fix an image that is tilted.)

- Avoid distractions: wait for a moving object to pass or set up your shot differently to hide elements that might disrupt the symmetry.

A visual balance doesn’t necessarily mean perfect symmetry, however. A composition can still feel well-balanced and harmonious even when visual elements are not identical on both sides of the frame.

Achieving asymmetrical balance

Another way to create a more dynamic image is by distributing visual elements with asymmetrical or ‘informal’ balance (see Figure 2).

The concept of visual weight is useful here. Visual features such as brightness, size, shape, colour and texture determine the ‘weight’ of objects in a photograph, pulling the viewer’s gaze to compelling parts of an image. Objects that appear dark, large, regular, colourful or rough (or are interesting for some other reason) tend to be ‘heavier’, attracting more attention than bright, small, irregular, neutral and smooth objects. It’s helpful to frame a shot so that less attention-grabbing areas and more attention-grabbing areas are balanced within the image, using the centre of the image as a fulcrum.

Figure 2

Here’s how to achieve asymmetrical balance:

- Select your focal point: choose a subject or moment that draws your attention. In this example, the focal point encompasses the faces of the child and mother. I was amused by the child’s expression and how it contrasted with that of the illuminated gorilla.

- Counterbalance your focal point with other elements: find a secondary subject elsewhere in the scene, one that is part of the moment but that grabs less attention (eg, the gorilla’s face), which will balance out and support your focal point.

- Apply the ‘rule of thirds’: mentally divide your frame into a 3x3 grid (as demonstrated above). Place your focal point off-centre, where one of the lines or an intersection point would be. Set up your frame so that the secondary subject (eg, the gorilla’s face) is on the opposite side. (Note: some devices, including iPhones, will show you 3x3 grid lines while you’re taking a picture if you activate this feature in the camera settings.)

- Consider shapes, colours and textures: remember, objects with more visual weight – often those that appear darker, larger, more regular, more colourful or rougher – attract more attention. And objects that are adjacent to each other can combine to make an area seem even weightier. Try to balance the weight on either side of your image in this way: position prominent (heavy) areas closer to the centre of the frame, compared with less prominent (lighter) ones that are on the opposite side. In the above example, the somewhat less prominent gorilla is a bit further from the centre than the more prominent focal point (the child and mother).

- Use leading lines: where possible, include lines and curves – such as those formed by a road, pathway or shadow – that point toward an area of interest within the scene and draw the viewer’s eye there.

- Use negative space: even if there is no secondary subject, you can use unoccupied space (eg, background) to balance your focal point and create a compelling composition (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

One further suggestion for creating a more engaging composition is to deliberately frame your shot so that the elements occupy a clear foreground, midground and background. You can also achieve pictorial balance by combining a heavy foreground with a striking subject in the midground (as in Figure 4).

Figure 4

By improving your composition, you guide the viewer’s eye through the frame, helping them understand and engage with your photo. A well-balanced composition aligns with a viewer’s sense of visual order, and it can produce a feeling of familiarity because it resonates with the viewer’s expectations. The thoughtful arrangement of visual elements can also shape your photo’s story. Let’s explore how.

Embrace storytelling

A picture’s potential to tell a story – engaging viewers emotionally or intellectually in a way that connects them with a situation or an event – is a fundamental element of impactful photography. This aspect of the medium is a major reason why photographs are so important in journalism and documentary work. The members of Magnum Photos, renowned for their ability to capture the essence of a scene or subject, often do so in a way that conveys a powerful sense of a compelling story unfolding (as you can see from examples of their work online). While not all photographers aim to document real-world events, the principles cultivated in documentary photography are valuable for helping beginners shoot better photos.

Conveying a story in a single frame can be challenging since a photo typically only records a discrete moment, but the following tips can help you achieve it.

Figure 5

- Define your narrative: consider the story you want to tell before taking the photo. For instance, ‘a community faces hardship and shows resilience during a time of crisis’. In the image above, I wanted to show how a small community coped during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Select your focal point: choose a main subject that anchors your narrative. This might be one person or a group of people (eg, the line of masked, social-distancing customers queuing for groceries).

- Set the scene: consider the setting where the story unfolds. Include elements in your frame that give a sense of time and place (eg, shop signage) and reinforce your narrative. Avoid including elements that introduce ambiguity or distract from the story.

- Choose the right moment: look out for a moment that helps to define the story’s essence, such as an action, expression or interaction. These can reveal how subjects are feeling and enhance your narrative.

Of course, you can also consider telling a story through a series of photographs, if one is not enough to convey the message you have in mind.

Visual storytelling allows viewers to meaningfully connect with your subject, creating a more authentic experience. It can also evoke a sense of familiarity by providing audiences with a recognisable context that they can understand, adding depth and emotional resonance. With that in mind, let’s turn to empathy and its role in taking better pictures.

Exercise empathy

Photography can produce strong emotions in viewers and prompt them to share the feelings expressed by the people in images (eg, viewing pictures of people smiling can make you feel happier). To allow viewers to empathise in this way, a photographer first needs to exercise empathy themselves, tuning into and then capturing the emotional experiences of subjects. ‘Every image is the direct expression of an emotion,’ the art critic Hilton Kramer wrote in an article for The New York Times about the photographer Gordon Parks. Influential photographers such as Parks demonstrate an ability to understand and share their subjects’ emotions, allowing them to capture authentic moments that reveal insights into the human condition. Empathy was one of Parks’s strengths. (He had many!) And experts agree that photojournalism is all about connecting with people on an emotional level.

When viewers see the struggle or triumph of someone in a picture, it can foster a sense of shared understanding because of the natural tendency people have to try to interpret the mental states of others (known as ‘theory of mind’ in psychology). Viewers seem to like pictures more when they try to understand the emotions and intentions of the people in them, as compared to when they evaluate other aspects. So, empathic picture-taking can translate to more meaningful and resonant images.

Showing empathy towards people when taking photos requires communication, respect, and building a connection. Use the following tips to connect with your subject and capture more authentic and compelling photos.

Figure 6

- Engage in conversation: relieve tension by striking up a conversation and building a rapport with your subject. Talking relaxes people, which can sometimes help you capture a more authentic photo. If someone is a stranger, I typically make a connection by complimenting their style or simply by saying, ‘Would you mind if I took your picture?’ (as in the image above).

- Show genuine interest: listen to what your subject has to say. Listening demonstrates a genuine interest in the story related to the shot.

- See another’s perspective: put yourself in the subject’s place. Imagine being on the other side of the lens to help you better connect with them. This insight might also inform your composition, framing and creative decisions.

- Be patient and discreet: give people space and time to relax and be themselves. The best shots often arise through patience. Being unobtrusive also helps. Sometimes, the most authentic moments occur when your subject is not paying any attention to the camera.

- Mind your body language: adopt a warm, open manner to put your subject at ease.

- Capture candid moments: be observant and look for natural and spontaneous moments rather than posed expressions. These often lead to more meaningful photos (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Aside from the kind of empathic connection that’s helpful for working with people, a sense of connection with the natural world can influence how you take photos of plants, wildlife and the outdoors. Feeling more attuned to nature by being mindful of what’s happening around you might prompt you to photograph a flower from a bee’s perspective, the moment when a bird feeds its chicks, or the drama of a stormy sky.

Patience also benefits those who take photos of natural scenes and wildlife. Observing and waiting enables one to capture magical moments during sunrise and sunset when lighting is soft, warm and diffused; animals as they hunt, feed, groom or care for their young; or landscapes with the right mix of clouds, lighting and atmospheric effects (see Figure 8). Thus, patiently connecting with both people and with the natural world can result in emotive and authentic images.

Figure 8

Seize the moment

So far, we have discussed how to take photos that provoke emotions and resonate with viewers when composition, storytelling and empathy combine. But another critical element that separates a good image from an exceptional one is timing.

The decisive moment, a term coined by the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, is about capturing a point in time when all elements in a composition come together perfectly, creating a visually compelling and meaningful image. It’s about seizing split-second opportunities to produce impact. These moments are often fleeting and may never happen again.

Observing events and anticipating moments when everything feels ‘just right’ requires a keen sense of time. My first discovery as a scientist was that people actually tend to be quite good at judging the passage of time, which makes it easier for them to anticipate future events. And, believe me, using this sensitivity to predict when and where to point your camera helps when taking photos in the real world (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

Here are some specific tips for taking perfectly timed photos:

- Visualise the exact moment you want to capture. Pre-focus on the area where you expect some action to occur (eg, the edge of the bridge from which people were getting ready to dive, in Figure 9). Then, recompose the shot as you see fit.

- Anticipate the action. Be ready to press the button to take a photo just before you expect the action to happen. This way, you’re more likely to catch the peak of the moment, when everything feels ‘just right’.

- Wait for situations to unfold naturally rather than contriving an image. Authenticity adds impact, and genuine expressions speak volumes.

- Use continuous shooting mode on your camera (called ‘Burst mode’ on an iPhone) to take multiple rapid-fire shots and increase your chances of capturing the perfect moment.

- Use a fast shutter speed and a high camera-sensitivity setting (if using a DSLR camera) when you’re in low-light conditions in order to freeze motion – crucial for capturing fast-moving subjects.

While composition, storytelling and empathy help to create images that are not only visually pleasing but also emotionally resonant, capturing a significant moment in time – one that would otherwise be lost forever – can make an image all the more remarkable.

Key points – How to take better photos

- Photography has many functions – and benefits. Whether you like taking pictures to express yourself, to remember what you’ve experienced, or to connect with others, photography can be a relaxing and fulfilling activity.

- Familiarise yourself with some key elements. Practising thoughtful composition, storytelling and empathy can enhance the impact of your photos.

- Aim for a balanced composition. Try setting up a symmetrical shot; or find an interesting focal point and counterbalance it with less prominent visual elements.

- Embrace storytelling. Consider what kind of story you want to tell, and select a main subject, setting and moment in time that substantiate it.

- Exercise empathy. Establish a connection with your subject – showing respect, interest and patience – to help you tune in to what’s happening and capture authentic experiences.

- Seize the moment. Stand by for those brief opportunities when everything about a scene feels ‘just right’, and have your camera ready when it happens.

Learn more

Experimenting with unconventional approaches

It would be a mistake to accept that there are inviolable rules in art, design or photography. Photographers sometimes challenge aesthetic norms intentionally to create unique, thought-provoking, or emotionally charged work. Even the composition guidelines that I shared earlier, while very useful, can be bent or broken. Unconventional practices can allow photographers to express themselves and take photos that stand out; consider Figure 10, which cuts off the head at the neck, even though the face is typically a crucial part of a portrait.

Figure 10

Here are just a handful of ways you might go about experimenting with your photos, with a view toward making them stand out:

- Look for unusual angles or viewpoints. Get low to the ground or shoot from above. Present familiar subjects or scenes from a fresh perspective.

- Play with light and shadows to create mood and atmosphere and to emphasise shape and form. For instance, you can photograph a subject that’s illuminated from the back to create a silhouette against a brighter background, as in Figure 11.

- Zoom in on detail to reveal features or textures that might otherwise go unnoticed – immersing the viewer in the scene.

- Use slow shutter speeds, or intentional camera movement while taking a picture, to add a sense of motion, dynamism or abstraction to your work.

- Experiment with photo-editing techniques to manipulate colours, contrast and other elements that can make your images pop.

- Explore creative techniques such as double exposure (ie, combining two or more images into a single frame) or light painting (ie, using flashlights or LEDs to ‘paint’ with light during a long exposure).

Figure 11

Balancing the novel and the familiar

I believe that taking better photos involves balancing two things: familiarity, that is, presenting something expected through a well-balanced composition and relatable narrative; and novelty, surprising viewers with something fresh and unique.

This view resonates with the idea of the brain as a prediction machine that processes familiar and novel information to make accurate judgments. It also relates to the psychologist Daniel Berlyne’s idea that people prefer stimuli with moderate amounts of complexity (ie, neither too simple nor too complex). Very simple or familiar stimuli may underwhelm the brain’s prediction-making ability, leading to low appeal. In contrast, overly complex or novel stimuli may overwhelm the brain. Thus, it makes sense that photos that balance familiarity and novelty, either presenting familiar content in a novel way or featuring novel subject matter in a relatable context, often have the most appeal.

Perhaps this is why social media hashtags like #liminalspaces (ie, images of familiar places that defy expectations) generate billions of views. Hollywood blockbusters often balance identifiable stories with shocking twists (eg, The Usual Suspects, 1995). And chart-topping hits similarly strike a balance between familiarity and surprise. Test this idea yourself: try to follow the Goldilocks principle by shooting photos with ‘just right’ amounts of familiarity and novelty for sufficient appeal. Even if you don’t become famous, you’ll still enjoy the result.

Links & books

For further examples of photos with excellent visual balance, I recommend visiting Peter Stewart’s website for his geometric compositions of buildings in Hong Kong and other scenes, as well as Michael Shainblum’s website, for his impressive natural landscapes and cityscapes.

British documentary photographer Olivia Arthur (a member of Magnum Photos) is known for her work examining social and cultural issues. It’s worth visiting her website to gain insights into her artistic style and storytelling techniques.

You can also find many creative compositions on Instagram: try searching for hashtags such as #streetgeometry_bw and #incredible_minimal.

It’s not uncommon for friends and family to ask an amateur photographer to photograph a wedding (or similar event). Or maybe you’re a photographer struggling to think of new ways to pose the happy couple. If you’re looking for some tips, check out my blog post ‘30 Ideas for Natural-Looking Wedding Portraits’, as well as my post ‘Your Must-Have Wedding Ceremony Photos’.

If, like me, you’re a photographer who enjoys documenting everyday life, have a look at my photo series ‘Eastham Fête: A Quintessential British Summer Fair’, which celebrates British culture and tells a story of tradition, community and joy.

Perhaps you appreciate the beauty in the mundane and want to take aesthetically ‘boring’ photos like those of the American photographer William Eggleston. If so, my blog post ‘How to Take Mundane Photos Like William Eggleston’ is for you.

The book Langford’s Basic Photography (10th edition, 2015) is an accessible read for those who want to go further into the fundamentals of photography.

YouTube channels, such as that of the photographer Scott Kelby, feature many helpful videos with guidance for building photo-editing skills.

Steidl is an excellent and prestigious publisher of photobooks from many renowned photographers, which you can explore on its website.