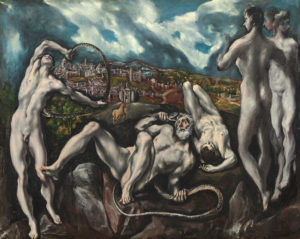

THE STYLISH STYLE: WHY IS MANNERISM WEIRD?January 17, 2024 If you go to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, you will see many wonderful things. You might recognize Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes or the portrait of Medusa’s head by Caravaggio. Most people will instantly go towards the major Botticelli works on display, like The Birth of Venus, Primavera, and The Adoration of the Magi (which includes the artist’s self-portrait on the right-hand side). However, few people will be ready for a rather strange painting on display at the Uffizi. It’s a Madonna and Child painting, but there’s something off: the Christ Child has an oddly long torso, with a large head and very pale skin. There is a herd of androgynous figures off to the left side, while a random, standalone column dominates the background. After looking at it for a minute, you then begin to see the weird, elongated features of the Virgin Mary, particularly her long neck. Well, that’s the reason the painting is called Madonna dal Collo Lungo, or Madonna with the Long Neck. And it’s okay to say that the painting is weird. It’s sort of meant to be weird. And that is the main thing you need to understand about Mannerism. Many people’s perception of art history typically involves the idea that the Renaissance brought about a renewed interest in classical art and philosophy, and it was nothing but perfect naturalism from then until the Impressionists. However, in the same way that people today are often very aware of generational differences, prioritizing naturalism in the visual arts has ebbed and flowed over the centuries. At the height of the Renaissance in Italy, between 1480 and 1520, many up-and-coming artists seemed to believe that with so many legendary masters running around, there was nothing truly great for them to do. Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, and Botticelli, as well as earlier masters like Donatello, Paolo Ucello, and Giotto, had all made great artistic innovations and breakthroughs, leaving little for everyone else. Young artists certainly tried to copy and imitate the great masters, but they realized this would not get them anywhere. Vasari, in fact, once attributed a quote to Michelangelo, where he once said, “Anyone who follows others never passes them by, and anyone who does not know how to do good works on his own cannot make good use of works by others.” Of course, he was commenting on imitating the ancient master sculptors. Still, he could have just as easily been commenting on the new generation of artists honing their craft through making studies of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. But rather than stick to imitation, some of this new generation of artists decided to blaze a new trail. They saw the renewed classical ideals in Raphael’s paintings and Michelangelo’s sculptures and chose to reject them. Plus, with the Protestant Reformation kicking off in 1517, perfection and naturalism no longer reflected their world. Europe was becoming increasingly chaotic, so these artists diverged from naturalism, trying to create something bolder and more stylized. By around 1530, with many of the great Renaissance masters having passed away, these new artists were creating some of the most unique paintings of the day. But this uniqueness meant a complete disregard for anatomical correctness and perspective, which almost always throws off people unfamiliar with the Madonna with the Long Neck. Created in the 1530s by the painter Francesco Mazzola, known as Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck is the quintessential Mannerist painting. It rejects the Renaissance ideals of anatomical naturalism in several ways. The Christ Child’s torso is far too long, and its head too large. His skin is pallid and gray, almost like that of a corpse. Some art historians have noted his limp left arm and how it resembles Michelangelo’s sculpture Pietà. The Virgin Mary’s body is oddly elongated, with a curving torso, spindly fingers, and long neck possibly serving as an example of the Mannerist figura serpentinata, or the posing and distortion of the body to evoke movement. Furthermore, the androgynous angels on the left show that the Madonna is incredibly tall, nearly twice their size. And finally, the lone column in the background. Among the ideals of the Renaissance was not just beauty and balance but logic. Things had to make sense. A single column not holding up anything, not serving any structural or architectural purpose, makes no sense and would seem out of place in an earlier painting. One of the other hallmarks of Mannerism was the greater inclusion of allegory and symbolism. Parmigianino does this very well in Cupid Making His Bow. The Mannerist distortion of proportion is again on display here, as Cupid’s legs seem far too long and his head too small. He carves his bow from a cherrywood branch while stepping on some books for support, representing the triumph of love over knowledge. Other artists also chose to include such symbolism, including Bronzino. When it comes to masterworks of Mannerism, Madonna with the Long Neck is often uttered in the same breath as Brozino’s Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time. While Bronzino is known mainly as a portraitist, this allegorical painting is often considered one of the great works of Mannerist painting. Cupid kisses his mother, Venus, laying his hands on her in an overtly erotic fashion. Meanwhile, Folly approaches them to shower them in rose petals, accidentally stepping on the rose bush’s thorns. The bald male figure, Time, rushes to hold up a blue sheet to shield the scene from whoever is supposed to be in the background. All the figures have some sort of distortion, whether Cupid’s odd, elongated body and his uncomfortable pose, Time overextending his arm, and Folly, a cherub-like figure contorted into the Mannerist figura serpentinata. While Bronzino’s portraits are often incredibly calm and stoic, that cannot be said for Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time. The lack of background and the figures’ layout makes everything seem chaotic and claustrophobic. Everything is all over the place, with bright colors contrasting, throwing the earlier Renaissance ideals like balance and harmony out the window. Scholars have long debated the meaning of the painting, with some saying it’s about forbidden passion while others claim it’s about syphilis. The word ‘Mannerism’ derives from the Italian word maniera, meaning ‘manner’ or ‘style’. It is, therefore, sometimes called “the stylish style.” I’m not sure if that’s supposed to be a literal translation, or possibly a euphemism because of its relative strangeness. But sometimes, rejecting a previous generation’s values is a good thing. People have good reason to question why we do things a certain way. And while Parmigianino and Bronzino’s works described above can serve as an example that going out on your own can produce some rocky results, it’s often just because some kinks need to be worked out. In the end, Mannerism did produce many truly marvelous works. One of Parmigianino’s earliest Mannerist experiments is a self-portrait he made at the age of 21, showing him reflected in a convex mirror his barber used; when Mannerism plays with perspective and form without seeming too strange. This is what the later great Mannerist painters did, like El Greco and the lankiness of his portraiture subjects and the stylized poses in his historical and religious works, or Tintoretto and his play on perspective in his Last Supper or use of allegory and symbolism like in Origin of the Milky Way. Yes, I still think Mannerism is weird. But there’s a certain beauty in its weirdness, which I always have respect for. | MORE ARTICLES |