What Is Kawaii?

The Japanese concept of kawaii—best translated as “cuteness”—has grown from a national trend to a global phenomenon. Sanrio’s Hello Kitty has been valued at $7 billion; the Oxford English Dictionary named an emoji its 2015 Word of the Year; and Nintendo’s Pokémon Go recently became the most downloaded game in smartphone history. The kawaii movement is wide in scope, spanning Manga comics, Harajuku fashion, and Takashi Murakami’s “Superflat” artworks, but what’s behind the aesthetic, and why is it so popular?

Japan’s culture of cute began in the 1970s with a youth movement developed by teenage girls, involving handwriting in a childlike style. The new script was given a variety of names, such as marui ji (round writing), koneko ji (kitten writing), and burikko ji (fake-child writing), and featured text with stylized lines, hearts, stars, Latin characters, and cartoon faces. Many scholars cite this trend as a reaction against the rigidity of post-World War II Japan, as the pursuit of kawaii enabled youth to find a sense of individuality and playfulness in an increasingly serious and depersonalized environment. While many schools initially banned this writing style, advertisers quickly caught onto the trend, using the new aesthetic to market products to the younger generation.

In 1974, the stationary company Sanrio launched the character of Hello Kitty, printing the now-iconic whiskered white cat on a vinyl coin purse. Forty-two years later, Hello Kitty has been placed on over 50,000 products in more than 70 countries, including toaster ovens, alarm clocks, airplanes, and even sex toys. In 2008, Japan named Hello Kitty as its tourism ambassador, an official invite to the rest of the world to join in on the adorability binge that is kawaii.

Japan’s culture of cute began in the 1970s with a youth movement developed by teenage girls, involving handwriting in a childlike style. The new script was given a variety of names, such as marui ji (round writing), koneko ji (kitten writing), and burikko ji (fake-child writing), and featured text with stylized lines, hearts, stars, Latin characters, and cartoon faces. Many scholars cite this trend as a reaction against the rigidity of post-World War II Japan, as the pursuit of kawaii enabled youth to find a sense of individuality and playfulness in an increasingly serious and depersonalized environment. While many schools initially banned this writing style, advertisers quickly caught onto the trend, using the new aesthetic to market products to the younger generation.

In 1974, the stationary company Sanrio launched the character of Hello Kitty, printing the now-iconic whiskered white cat on a vinyl coin purse. Forty-two years later, Hello Kitty has been placed on over 50,000 products in more than 70 countries, including toaster ovens, alarm clocks, airplanes, and even sex toys. In 2008, Japan named Hello Kitty as its tourism ambassador, an official invite to the rest of the world to join in on the adorability binge that is kawaii.

But Hello Kitty is not alone. In fact, each of Japan’s 47 governmental offices has its own kawaii mascot, such as the rosy-cheeked bear Kumamom for the bullet train and the wide-eyed Prince Pickles for the police force. Pokémon has developed another 700 kawaii creatures

over the past 20 years, some of which are currently running virtually

rampant in cyberspace. Emojis, bitmojis, and even those adorable Casper

subway advertisements all take root in the kawaii philosophy.

While kawaii characters are diverse, spanning species both real and imagined, they often follow a basic formula. Kawaii creatures have limited facial features—two wide eyes, a small nose, and maybe a dot for the mouth—rendering them emotionally ambiguous and enabling viewers to project upon them. (For this reason, iPhone emojis have been criticized as not kawaii enough by some Japanese consumers because they feature a greater amount of emotional specificity.) Almost always outlined in black, kawaii characters are pastel-colored, graphically simple, and childlike. Designed to elicit a sense of nostalgia, they often feature big heads and little bodies in order to match the proportions of infants and baby animals.

Scholars have suggested that people grow attached to kawaii characters precisely because of their youthful nature, which elicits the evolutionary impulse to care for the young. “Hello Kitty needs protection,” the sociologist Merry White once explained. “She’s not only adorable and round, she’s also mouthless and can’t speak for herself.” Tamagotchis—a nostalgia-inducing timecapsule for those who came of age in the ’90s—are Japanese gadgets that epitomize this theory, as they require users to look after small digital pets that are sweet and helpless. Reportedly, some Pokémon Go users have opted out of evolving their pokémons, preferring to keep them in an infantile state rather than growing their powers.

While kawaii characters are diverse, spanning species both real and imagined, they often follow a basic formula. Kawaii creatures have limited facial features—two wide eyes, a small nose, and maybe a dot for the mouth—rendering them emotionally ambiguous and enabling viewers to project upon them. (For this reason, iPhone emojis have been criticized as not kawaii enough by some Japanese consumers because they feature a greater amount of emotional specificity.) Almost always outlined in black, kawaii characters are pastel-colored, graphically simple, and childlike. Designed to elicit a sense of nostalgia, they often feature big heads and little bodies in order to match the proportions of infants and baby animals.

Scholars have suggested that people grow attached to kawaii characters precisely because of their youthful nature, which elicits the evolutionary impulse to care for the young. “Hello Kitty needs protection,” the sociologist Merry White once explained. “She’s not only adorable and round, she’s also mouthless and can’t speak for herself.” Tamagotchis—a nostalgia-inducing timecapsule for those who came of age in the ’90s—are Japanese gadgets that epitomize this theory, as they require users to look after small digital pets that are sweet and helpless. Reportedly, some Pokémon Go users have opted out of evolving their pokémons, preferring to keep them in an infantile state rather than growing their powers.

- Julien's Auctions: Street Art Now February 2016

The effect of the aesthetic is also to return us to a childlike state. Many from the so-called kawaii generation also desire to be kawaii themselves, whether through infantile voices or juvenile dress. For example, the kawaii

trend of “Lolita fashion” promotes a Victorian style of clothing, ripe

with innocent-looking petticoats, ruffles, pastel colors, and large

ribbons and bows. Whether Lolita-kawaii is named after Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel or is Japanese in origin, however, is still a hotly debated topic.

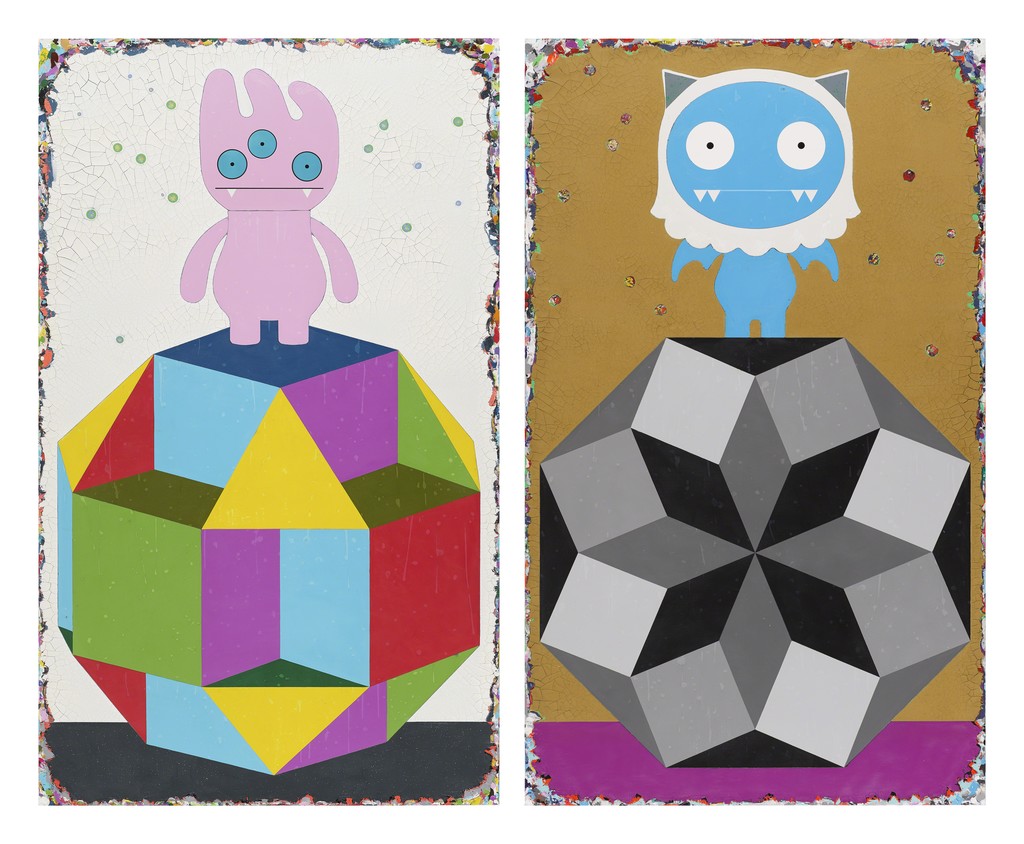

The Lolita aesthetic is not the only sub-brand of kawaii thriving today. Guro-kawaii (grotesque cute), ero-kawaii (erotic cute), kimo-kawaii (creepy cute), and busu-kawaii (ugly cute) have all emerged as alternatives to the more traditional style of Hello Kitty and Pikachu. Meanwhile, contemporary artists Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara have ushered kawaii into the fine arts, creating their own series of wide-eyed characters that range from the vapidly cute to the uncomfortably sinister.

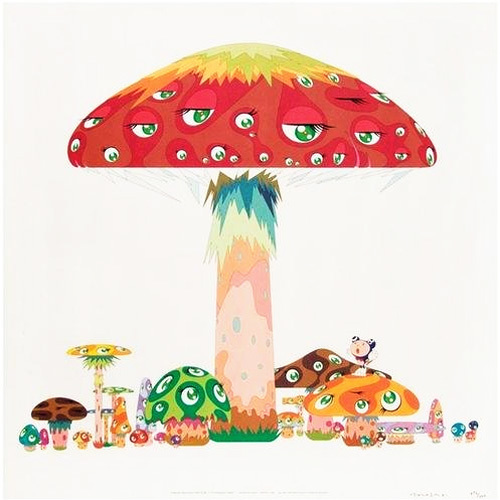

In his paintings and sculptures, Murakami reminds viewers that the style of kawaii carries with it a certain darkness. His depictions of cartoon mushrooms, for example, appear entirely joyous at first glance, but also recall the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For Murakami, the kawaii aesthetic acts as an enduring symbol of the infantilized nature of occupied Japan after World War II—a manner through which people found escape from the trauma of war.

The Lolita aesthetic is not the only sub-brand of kawaii thriving today. Guro-kawaii (grotesque cute), ero-kawaii (erotic cute), kimo-kawaii (creepy cute), and busu-kawaii (ugly cute) have all emerged as alternatives to the more traditional style of Hello Kitty and Pikachu. Meanwhile, contemporary artists Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara have ushered kawaii into the fine arts, creating their own series of wide-eyed characters that range from the vapidly cute to the uncomfortably sinister.

In his paintings and sculptures, Murakami reminds viewers that the style of kawaii carries with it a certain darkness. His depictions of cartoon mushrooms, for example, appear entirely joyous at first glance, but also recall the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For Murakami, the kawaii aesthetic acts as an enduring symbol of the infantilized nature of occupied Japan after World War II—a manner through which people found escape from the trauma of war.

Since its beginnings, the kawaii craze

has been a rebellion against the seriousness of adulthood—a

counterbalance to the harshness of the real world. Under the strain of a

polarizing election cycle, it is perhaps no wonder why over 15 million

people have decided to temporarily tune out the news for a dive into

Pokémon Go. The app invokes the child within, encouraging users to find

imaginary friends and care for them, or at least so I’ve heard. This

writer is still at level one.

—Sarah Gottesman

Cover image: Takashi Murakami, Rainbow Flower - 4 O'Clock, 2007. Image courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

—Sarah Gottesman

Cover image: Takashi Murakami, Rainbow Flower - 4 O'Clock, 2007. Image courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.