Analysis

The ‘Winner Takes All’ Art Market: 25 Artists Account for Nearly 50% of All Contemporary Auction Sales

Here's why the market is as top-heavy as ever—and what it means for the future.

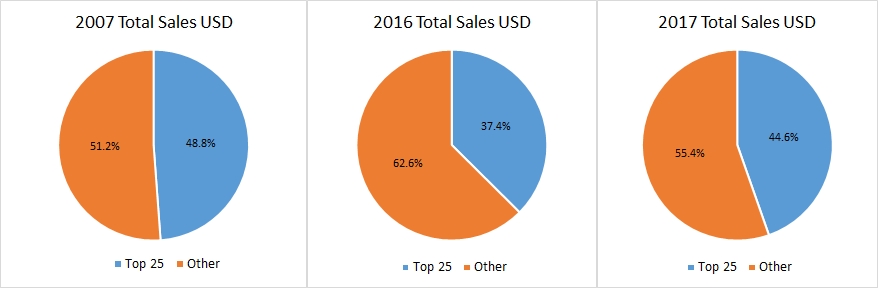

Just 25 artists are responsible for almost half of all postwar and contemporary art auction sales, according to joint analysis by artnet Analytics and artnet News. In the first six months of 2017, work by this small group of elite artists sold for a combined $1.2 billion—44.6 percent of the $2.7 billion total generated by all contemporary public auction sales worldwide.

Our findings quantify what many market-watchers have long observed: As increasingly wealthy buyers compete for a shrinking supply of name-brand artists, the art market has become highly concentrated at the top. Nevertheless, the reality—that the work of just 25 artists generated almost as much money at auction as the work of thousands of other artists combined—may be even more extreme than some realized.

Winner Takes All

“The contemporary art market is a good example of a ‘winner-takes-all’ market, where a very small proportion of artists is responsible for a very large market share, and a very large proportion has a very small market share,” says Olav Velthuis, a professor of sociology and anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. The same phenomenon is evident among athletes, actors, and musicians, he notes.

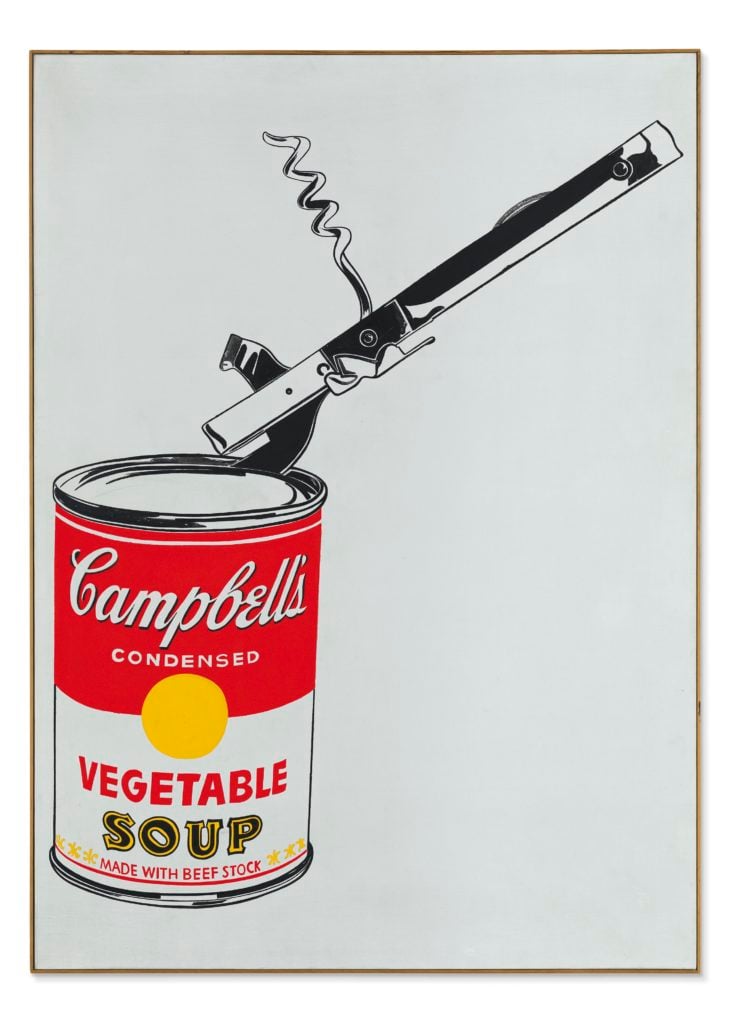

The list of the most profitable 25 artists includes blue-chip Pop and Abstract Expressionist names like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Cy Twombly, as well as living artists like Gerhard Richter, Peter Doig, Christopher Wool, and Mark Grotjahn. The only women to make the list were Agnes Martin and Yayoi Kusama.

Source: artnet Analytics ©2017.

(We defined “postwar and contemporary” as works created after 1945 and based our analysis on prices supplied to artnet’s database by 420 auction houses worldwide in the first half of 2017. The data set includes 70,507 works offered for sale during this period.)

The top-heaviness is more extreme this year than last. In the equivalent period in 2016, the top 25 artists accounted for 37.4 percent of all postwar and contemporary auction sales, according to our data—7.2 percent less than this year, but still a dramatically outsize proportion of the total.

Source: artnet Analytics

A New Era

It was not always this way. There was a time when the bluest of blue-chip did not rule the high-end art market with such a mighty hand. In the 1980s, the emerging class of major collectors was more focused on buying new art on the primary market—Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Gerhard Richter—than snapping up trophies from the recent past at auction.

Andy Warhol, Big Campbell’s Soup Can with Can Opener (Vegetable) (1962). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

But after the market crashes of 2000 and 2008, “you saw a more substantial shift to resale material and proven masters,” says Allan Schwartzman, the co-founder of Art Agency Partners and chairman of global fine arts at Sotheby’s.

This shift was made more extreme by the emergence of ultra-wealthy new collectors in Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Gulf, who sent a jolt of fresh money into the auction market. “Most of those new buyers were not entering the market with [purchases of work by] the artists of their generation—they were entering with the most important works by the most important artists,” Schwartzman notes.

The numbers bear this out. In the first half of 2007, when many of these new collectors began flooding into the market and a focus on brand names had firmly taken hold, the top 25 artists accounted for 48.8 percent of total auction sales, a slightly greater proportion than they do today.

Winners and Losers

What do the winners of this 21st-century market dynamic have in common? Perhaps unsurprisingly, almost all artists on the 2017 list are white and male. Thirteen, or just over half, of the top 25 are American.

Courtesy Phillips

These statistics surprised Scott Nussbaum, the head of 20th-century and contemporary art at Phillips. “Thinking about how the market has grown in the past decade, [I would presume] it has become more progressive with artists of color, female artists, artists outside the historical canon we all grew up with,” he says. “These numbers just seemed to reinforce the total opposite.” He notes that the same number of women (two) and the same number of African-American artists (one, Jean-Michel Basquiat) appear on the list in 2007, 2016, and 2017.

Beyond their demographic similarities, the vast majority of these artists also have a recognizable style, making their works appealing trophies. “For many buyers, it is important that their peers recognize the works they own—and that is only possible if the pool of artists is relatively small,” Velthuis notes.

At the same time, most of these anointed ones—such as Warhol, Rauschenberg, and Richter—are also quite prolific. “When you have a combination of an artist who, on a per-work basis tends to command fairly high prices, plus a critical mass of work, it’s no surprise that they’re at the top of the list,” Nussbaum says.

Solving the Supply and Demand Puzzle

Still, some things have changed over the past decade. New additions to the list in 2016 and 2017, such as Keith Haring and Jean Dubuffet, illustrate the extent to which the market is willing to revisit previously overlooked talents as the supply of established favorites wanes. By the same token, the fact that artists like Lucian Freud and Jasper Johns dropped off the list between 2007 and 2017 does not necessarily mean their markets are weak, but rather that there are simply fewer top works available.

Source: artnet Analytics

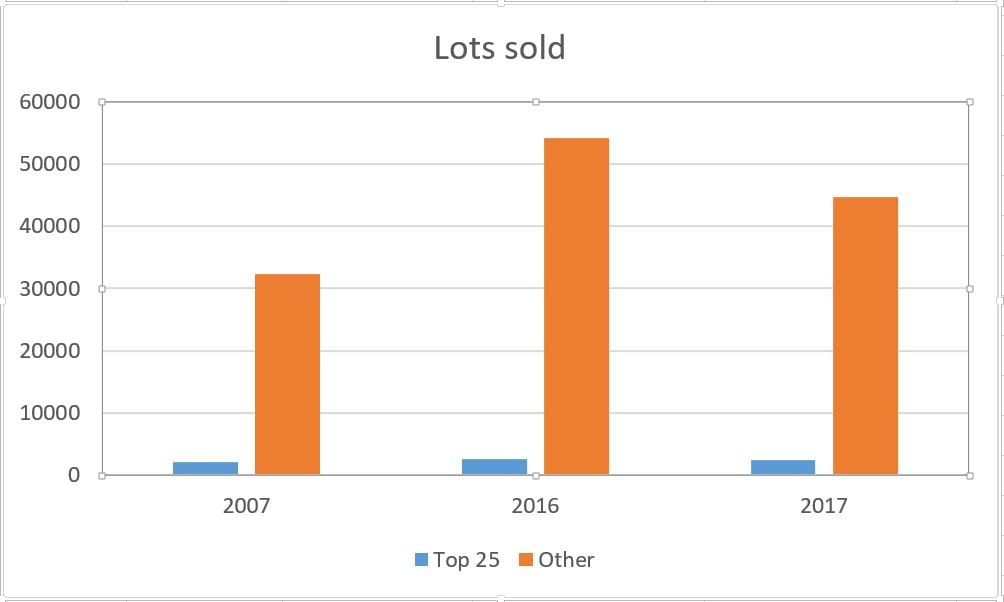

Indeed, the question of who makes it into the upper echelons of today’s auction market has far more to do with supply than demand, experts say. Looking at artnet’s data, Benjamin Mandel, a global strategist for J.P. Morgan Asset Management, notes that between the first half of 2016 and the first half of 2017 the number of lots sold fell by 17 percent, but average price generated by these lots rose by 25.6 percent—a “puzzling dynamic.”

“Usually, when there is a lot of demand, it increases the quantity of goods sold,” because the market responds to meet the desires of consumers, Mandel notes. In this case, “the quantity sold went down, but price went up.”

What this suggests, Mandel says, is that the top-heavy market for postwar and contemporary art has been shaped most recently by a lack of supply. There are simply not enough works to fulfill the demand that exists. As a result, when top works by top artists do make it to market, their prices climb further and further upward.

Not the Whole Story

Of course, looking at the top slice of public auction sales offers a very incomplete picture of the market as a whole. One major painting that sells for $20 million can shoot an artist into the top 25, even if his or her work does not consistently sell for those kinds of stratospheric sums. The figures are also self-reported by auction houses, a small number of which—particularly in China—have been accused of recording bids for works that were never fully paid for as final prices.

These numbers also do not account for works sold privately by auction houses or galleries—a significant portion of the market for contemporary art. Schwartzman says there are a number of artists who routinely sell out exhibitions on the primary market but whose auction record is comparatively low because only minor works have hit the block. (He offers Kai Althoff as an example.)

Similarly, some historically significant and sought-after artists like Jasper Johns have not had a major work appear at auction for several years, which puts their auction market out of sync with the private market.

“There are new players who are major drivers of the market who don’t know Jasper Johns,” Schwartzman notes. “So what will happen when the next major Johns comes forward? In all likelihood, it would probably carry a relatively conservative estimate because there hasn’t been a proven record of lots of money spent, despite rumors of the primary market.”

Another important caveat: By and large, the artists themselves do not directly benefit from these massive auction sales—only their collectors do. “The artists, if they are still alive, receive at best only a small percentage of resale royalties on these sales, but in most cases, don’t receive anything,” Velthuis notes.

What’s Next?

Whether a small number of highly coveted artists will continue to subsume a larger and larger proportion of auction sales hinges on the answer to a much bigger question. “It depends on whether the trend in inequality will continue… and it’s hard to say whether inequality in income and wealth will change anytime soon,” Mandel says.

Some market players are hoping this top-heavy dynamic will eventually have to give way to something more balanced. “There’s a lot of other great art that’s equally significant that is not these top 25 names,” Schwartzman says. “As supply decreases and number of people looking for art increase, there is so much great art that could come forward.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

SHARE

Article topics