On View

What Does the Art Institution of the Future Look Like? Here Are the 4 Big Ideas Driving the Ambitious New Shed Art Center

From Björk to Boots Riley, the program aims to surprise you at every turn.

What can we expect from The Shed, the soon-to-open $500 million new cultural center on the far west side of Manhattan? The stated mission of the nonprofit is to commission, develop, and present original works of art across all disciplines, including projects that combine art forms in new and unexpected ways.

Like anything truly new, it’s hard to imagine what it will look like until it arrives. Amid intense curiosity—and no small amount of skepticism about the loftily-funded organization—the single biggest factor that seems to be driving fascination with and confidence in the project is CEO and artistic director Alex Poots, the forward-thinking veteran of the Manchester International Festival and Park Avenue Armory. Ahead of The Shed’s grand debut, we spoke to Poots about his ambitious plans and the big ideas behind the program.

1. Separating art into high and low is corrosive.

The Shed’s eclectic inaugural lineup includes contributions from figures as diverse as musician Björk, indie film director Boots Riley, and German painting legend Gerhard Richter. Poots says his childhood played a big role in shaping his view that art is no place for artificial distinctions between the elite and the masses. When he was learning to play the trumpet, “I was trained classically, but I played pop and jazz. They were all important to me, so there wasn’t a sense that one style was more precious than another. That’s something that has interested me through my entire career,” he says. “This idea of high art and low art I find really corrosive and patronizing.”

Poots also isn’t interested in making decisions based on what format artists are working in, how old or young they are, or how advanced they are in their craft. What’s important is their talent and how their work resonates in society—that holy communion between an artist, their work, and the public. “You can be a place for early career as well as more established artists,” he says. “Everything we do is seen through the prism of making work, commissioning it, and presenting it. There is a fluidity to that which is becoming more and more important… Things are not black and white.”

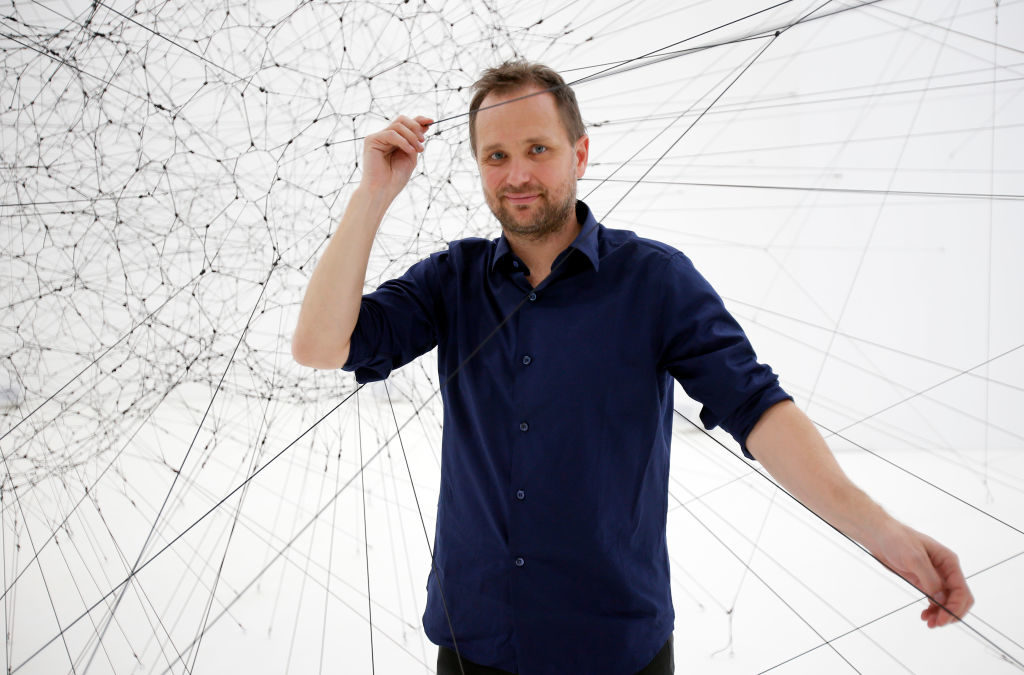

Founding artistic director and CEO of The Shed, Alex Poots. Photo by Craig Barritt/Getty Images for The Shed.

2. True artistic freedom comes when one isn’t responsible to anyone in particular—other than the public.

The Shed famously began as a pet project of former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg. It was part of the original deal struck between the city and developers in 2005, when the city paved the way for the private Hudson Yards development of apartments, office space, and retail. Part of the agreement involved staking out city land for a non-profit cultural facility.

Poots remembers hearing Bloomberg and former deputy mayor of economic development Daniel Doctoroff, who is now The Shed’s board chair, say that they wanted an art center that would be unlike anything else in the city. “It should keep New York on the cutting edge and it should be complementary,” he recalls. “So from my perspective, that was a hallelujah moment. Because this wasn’t city leadership trying to come up with a vision for an arts center, which probably would not have been a good idea because it’s not their métier. It wasn’t a playground for private development. It was a civic responsibility to the city.”

The support from the city (which also came in the form of a $75 million grant) was supplemented by hundreds of millions of dollars in private donations. And the sum allowed the architects—Liz Diller, with David Rockwell—to create “the first building I’ve ever seen that really has almost everything you could ever want,” Poots says. The eight-story structure contains a movable outer shell that can create flexible indoor and outdoor event spaces, as well as a creative lab for artists, gallery spaces, and a theater and rehearsal space.

3. The best projects don’t follow an existing model.

Two and a half years ago, Poots asked Turner Prize-winning artist and Oscar-winning filmmaker Steve McQueen, who he has known and worked with for decades, to think of an idea for The Shed. McQueen, who works across media and slips seamlessly between big-budget Hollywood and the rarefied art world, seemed like a natural fit. Poots didn’t offer any restrictions. In turn, McQueen raised the notion of trying to imagine what the history of African American music would sound like. (“He hears very visually,” Poots explains. “He had this idea that he could see and hear a family tree.”)

While some curators might have pushed McQueen toward slightly more well-trod terrain, Poots instead consulted Maureen Mahon, an associate professor of music at New York University. Together, the trio built out a team for the project, including 27-time Grammy Award-winner Quincy Jones, producer Dion ‘No I.D.’ Wilson, A&R executive Tunji Balogun, and music director Greg Phillinganes. This all-star lineup will support 25 emerging musicians and special guests who kick off the performances on April 5. “Soundtrack for America,” the five-night concert event, “does encapsulate a lot of our ambitions,” Poots says. “It’s not binary.”

4. Prioritize outreach. It won’t just help the community—it will make your program better, too.

Poots describes it as a “gift of an opportunity” that when he arrived at The Shed three and a half years ago, “we had no building, no office, no staff, no checkbook.” One of his first hires was Tamara McCaw (who is now chief civic program officer), with whom he developed a program with a group of performers from Brooklyn who are experts in flxn, a form of street dance with roots in Jamaican bruk up. Working with the 16-person collective, whose members range in age from 18 to 26 years old, Poots and McCaw developed a three-year program that taught students in schools across the five boroughs this particular style of dance activism. They quietly expanded the program to ten, then 20, and now 30 schools. “We’re trying to show or enable these young people to realize the power that the arts can have not only on their own bodies and talents but also on their own destiny,” Poots says. And what resonates in schools helps him understand what might work back at The Shed.

Poots is under no illusions. Of The Shed’s admittedly ambitious programming, he says: “I know we’re going to fail sometimes.” But he’s optimistic anyway. “Approaching what we do in a rounded and wide ranging way, I have to believe will have some positive effects.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics