Opinion

How Will Advanced Technologies Impact the Art World? 3 Takeaways From the Serpentine’s Future Art Ecosystems Report

The Serpentine's chief technology officer and its curator consider the future of art and technology from an infrastructural perspective.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world, arts organizations have been grappling with a forced migration to the digital realm, while simultaneously reorganizing their internal operations to meet the demands of a new reality. Budgets were frozen, staff put on furlough, programs and exhibitions postponed or canceled, and business plans and fundraising campaigns were severely undermined.

Given the contemporary art field’s heavy reliance on physical spaces, in-person networking, and crossing of borders, lockdown presents a devastating disruption. But while COVID-19 may be unprecedented, it has brought to the surface underlying issues and forced us to face a series of uncomfortable realities and big questions concerning the future of the sector.

Yesterday, the Serpentine Galleries launched the “Future Art Ecosystems: Art x Advanced Technologies” report, produced in collaboration with the strategy studio Rival Strategy, and focused on technologies’ impact on the arts. It offers alternative propositions for rebuilding the sector in the near future.

An Art Basel visitor uses a VR headset to view work by Jacolby Satterwhite in 2018. Photo by Harold Cunningham/Getty Images.

The scramble to embrace the digital space as—temporarily—the only site available has made clear that a strategy of mirroring offline programming online is risky, and doesn’t necessarily yield quality results or the desired levels of engagement. It’s clear that the arts have generally suffered from underinvestment and slow adaptation to the digital world in comparison to other sectors, even as the temporary de-centering of the physical gallery has made it obvious that advanced technologies such as AR and VR have a major role to play in shaping alternative pathways to experiencing art.

Galleries are now reopening, but without a reliable vaccine or treatment and with the specter of repeat lockdowns looming, it’s clear that a serious change is necessary for longer-term survival and relevance. As exhibitions and art fairs go digital and cultural experiences flatten, the immediate challenge is in competing for audience attention with the likes of Netflix, Fortnite, and Animal Crossing. The need to reposition the art organization within this landscape is an existential necessity. The fact that no institutions have yet joined forces (and budgets) to drive traffic to shared online programming is just one example of a lack of necessary strategic thinking in the sector.

Over the course of the last few years there has been a rapidly increasing engagement and investment in the development new technologies for art, both within the art industry and outside of it: Apple’s [AR]T Walks, Hauser & Wirth’s ArtLab, TeamLab’s Borderless museum, and a rash of VR artworks peppered across group shows and biennales. What seems different this time is the infrastructural change that is being orchestrated, and the overlapping transformation across industries as a result of a “technology first” approach.

It’s no exaggeration to say that we are in a moment of history in which all layers of our art systems face active and necessary revision. The use of advanced technologies by artists—and the increasing interest of the tech sector in developing its own contemporary art infrastructure—are destabilizing the systems of art as we have known them (and perhaps taken for granted).

Below, we summarize the three non-exclusive models our report offers for how the interfaces between art and advanced technologies are likely to be shaped over the next decade and the big questions that they leave for the present moment:

1. Art Could Be a Source of Opportunity for the Technology Sector

Ralph Pritchard. Courtesy of Serpentine Galleries.

Today, the tech sector is expanding into finance, healthcare, and education as tech companies require absorption of existing industries in order to expand their market share and meet mid-term revenue projections. For example, Amazon is poised in the next year to make a major push into healthcare, as highlighted by New York University marketing professor Scott Galloway in his recent talk for the Digital-Life-Design conference, “The Four Horsemen Post-Corona.”

We should expect to see an integration of the cultural sector, specifically those heritage institutions that are either repositories of historical knowledge or producers of niche contemporary experiences. In the age of advanced biotech, for example, natural history museums face a coincidental pivot from custodians of lost species to vast biological data warehouses, from which active scientific enquiry and biotech startups can build. The recent appointment of David Gurr, the head of Amazon’s UK and Ireland operations, as the director of the National History Museum in London may be seen as a step in the direction of tighter ties and latent pivots.

Or will tech build out its own cultural infrastructure on the back of its entertainment wing? Google, Apple, Samsung, and HTC have all shown aspirations for bespoke cultural programs or institutions. However, for cultural programs to succeed, they require a buy-in that isn’t based on a commercial value proposition. Given the growing public suspicion toward big tech, the question is: Can public arts organizations and artists come up with viable strategies to keep their work going without undermining their own integrity?

2. Ambitious Large-Scale Art Projects Can Soon Be Brought Directly to the Paying Public

teamLab’s Universe of Water Particles on a Rock where People Gather (2018). Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Our report identifies a new type of actor on the art–tech horizon: the art stack. An art stack is a vertically integrated art studio that resembles more a corporation than it does a traditional artist studio. Employing specialized staff, developing bespoke technologies and business models, art stacks present a fascinating hybrid that has more agility and capital than most traditional art institutions. Examples are teamLab, the likely soon to be announced re-articulation of Pace X, Acute Art, and the early stage potential of artistic practices such as Refik Anadol’s and Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s.

Scaling artistic practice and art institutional offerings is at the heart of the art stack model. Scaling is also what is required for a more leveled engagement with the tech industry, yet scaling carries a risk of reducing sophistication and nuance that good art is generally credited with. Could creative scaling then become a pursuit in and of itself for arts organizations and artists?

3. Art Is a Strategic Cultural Asset

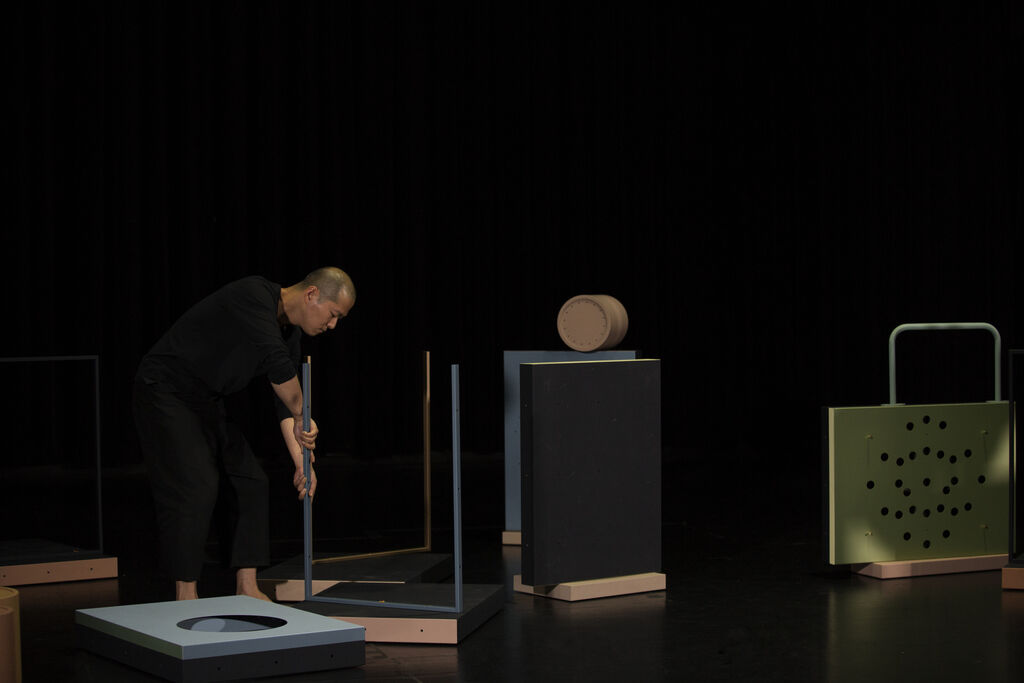

Ian Cheng, Emissary Sunsets The Self live simulation and story, infinite duration, sound (2017). Courtesy of the artist, Pilar Corrias, Gladstone Gallery, Standard (Oslo).

How should the historical value of the public art field be preserved and strengthened in this moment of accelerated change? One path might be to consider the role of art in a more holistic and mission-oriented approach to innovation and public good, advocated by the likes of Marianna Mazzucato, an economist and the founder and director of the University College London’s Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. Aligning art’s potential for creative research and development with the need to develop a more systemic understanding of value around societally disruptive technologies opens up a new vista for art as a bridge between worlds.

While, historically, the art field has been wary of having its work evaluated on the basis of metrics for measuring impact, this rejection is also what has led to reduced say in their framing and implementation by national and private funding bodies. If cultural infrastructure is to be transformed, systems of measurement must become an area of innovation in and of themselves. With new approaches to understanding the impact of measurement in a more holistic way, the highly charged matter of “metrics” needs to be finally tackled head on in order to evade another wave of cosmetic changes that don’t actually address the foundations.

The path toward a fully functioning 21st-century cultural infrastructure requires an honest questioning of implicit assumptions, underlying biases, and, crucially, substantial investment and transformation of existing systems of art. A question becomes ever more prescient in a moment when countries are issuing significant bailout funds to their cultural industries. Perhaps this is the biggest choice of all: to bailout or invest in rebuilding?

Jakob Kudsk Steensen, Catharsis (2019-20). Supported by CONNECT, BTS Outdoor installation at the Serpentine Galleries. Photo: Hugo Glendinning, courtesy of the artist.

None of these developments represent quick-to-implement solutions to the myriad of challenges that now face the art industry as it begins to move through a necessarily challenging period of history. But what this process of interrogating the impacts of advanced technologies on the arts has shown us, is that the underlying infrastructure and the platforms on which the art field runs today are what is at stake in defining its mid- to long-term trajectory and potential.

At present, there are other industries and “outliers” that are redefining and building systems, and should there be no concerted action to take a proactive stance, the art field will be remade by them. Arts ecosystems as they exist today must either learn to see, understand, and make decisions that act on these developments, or these decisions will be made for them.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

It looks like you're using an ad blocker, which may make our news articles disappear from your browser.

artnet News relies on advertising revenue, so please disable your ad blocker or whitelist our site.

To do so, simply click the Ad Block icon, usually located on the upper-right corner of your browser. Follow the prompts from there.

SHARE