|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Sunday, August 4, 2019

What Galleries Should Be Doing to Maximize Profits on the Internet

ART MARKET

Cha-Ching: What Galleries Should Be Doing to Maximize Profits on the Internet

By Edward Winkleman and Patton Hindle

JAN. 11, 2019

Find a class curriculum for arts administration, business, or marketing, and we can almost guarantee How to Start and Run a Commercial Art Gallery by Edward Winkleman will be listed on the syllabus. For the past decade, the comprehensive guide has helped fledgling gallerists get off the ground (or perhaps more often, encourage potential gallerists to steer clear of the expensive endeavor all together!). But a lot has changed since the book came out in 2009, not least of which is the proliferation of the internet.

Which is why Winkleman teamed up with Patton Hindle to co-author a revised second edition of the book, which was released just last month. Hindle—formerly Artspace's own director of partnerships, currently working as Kickstarter's director of arts—and Winkleman—the founding-director of the Moving Image Video-Art Fair, and owner of the now-defunct Edward Winkleman Gallery—added a whole new chapter about how galleries can leverage the power of the internet. Read the excerpted chapter below.

...

Over the last decade there have been significant changes in the way the art world operates. While the Internet and e-commerce have revolutionized just about every industry, the art world has been slow to develop with them. However, we are finally seeing significant moves toward innovation within e-commerce and the art market. Several online sites have cropped up to help facilitate sales; social media has drastically altered how dealers and artists communicate; and print magazines are increasingly having to move online to stay viable. In this chapter we’ll walk through several of these changes and how you can use them to your advantage in running a gallery.

ART AND E-COMMERCE

There are several online sites that allow for the sale of artworks to take place through a variety of ways. Artnet (www.artnet.com) was the first of the online players. Founded in 1989, the site continues to exist as a listing site for galleries, an auction price database, an online auction site, and an art news outlet. Galleries can pay a monthly subscription fee of $300–$400 per month to list available works by their artists. Interested clients can click to contact a gallery and request further information and pricing. Additionally, if you’re working in secondary-market sales, you may consider an annual subscription to the price database, which shows all previous auction records for an artist and can help you determine fair market value for a secondary market artwork. This information does not come cheaply though. A day pass will set you back $32.50 for a mere 5 searches, and annual memberships range from $450 per year for 150 searches to $1,175 per year for 450 searches. Pricing for more searches must be discussed with Artnet directly.

Perhaps one of the biggest competitors to the Artnet model is Artsy.net. Founded in 2010 by Carter Cleveland, Artsy began as an art genome project aiming to make art accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. They have since shifted their model to one somewhat similar to Artnet. They offer galleries monthly subscriptions to list their works (ranging from $400 to $5,000), run auctions online with nonprofit partners and Sotheby’s and Phillip’s auction houses, host an online magazine, and also offer art fair previews in advance of a fair opening. Artsy has seen significant growth in its user base and has had significant fund-raising from notable people in the contemporary art world, including Larry Gagosian, Dasha Zhukova, and Marc Glimcher. Its ease of use as a site makes it great for discovering new artists and artworks, which of course can prove a valuable way to reach new collectors.

One of the few actual e-commerce sites within the art world, Artspace.com, founded in 2009, has set itself apart from the listing sites by actually offering the ability to transact online (full disclosure: Patton worked at Artspace as the director of gallery and institutional partnerships for three years). Founded by Chris Vroom and Catherine Levene, Artspace aimed to help galleries, nonprofits, and publishers move inventory that might not easily reach the right collectors as a nonprofit may not have a sales staff, or a gallery may be focused on selling the $500,000 piece rather than the $5,000 or $10,000 piece sitting in storage. Artspace operates on a success-based model, meaning if you don’t sell you don’t have to pay anything. If a work sells, they take a 20 percent commission on works under $20,000 and a 10 percent commission on works over $20,000. Artspace also manages the relationship with the client for you and handles the logistics. This can be an easy, no-risk way to test out offering work online; however, you should note you will not have direct correspondence with the collectors.

Finally, 1stdibs.com has been dominating the design marketplace for years now. Founded in 2001 by invitation only, 1stdibs began as a listing site for furniture and design dealers. It has expanded over the years to include art and also allowed for e-commerce in which collectors can directly transact online. If your gallery model includes design or secondary market prints, 1stdibs could be a great way for your to test out your presence online. Many galleries who were very happy to work with 1stdibs in the beginning, however, have recently begun to grumble about some of their newer policies, which intercede between the gallery and the buyer. This may be worth considering when you’re looking for online platforms to help your new gallery grow.

The 2016 TEFAF market report noted that online sales were the only part of the art industry to see growth in 2016; auctions, gallery sales, and fair sales were all in decline. It’s worth noting that above a certain price threshold you may expect a collector to ask to see the work in person before buying. Online primary market sales still tend to be easiest under the $20,000 price point. But increasingly collectors note that they appreciate the anonymity of purchasing art online, and it can remove some of the stressors of having to either be physically in the same location as a gallery and the intimidation of walking into a gallery.

SOCIAL MEDIA

We’ve discussed this earlier under promotional habits, but it is worth reiterating again here as it becomes very much part of your digital marketing presence. As it stands now, social media is free to use and a way for you to have a direct line to your community. It can be an excellent way to build buzz around an exhibition or artist, as well as to share the gallery’s point of view. Facebook was the go-to tool for many years and still is helpful in listing your exhibitions and inviting friends to help spread the word about an opening. However, engagement on business pages has seen a decline as more and more galleries, artists, and collectors are turning toward Instagram for sharing information. This simply makes sense in a visual industry to be sharing imagery of an artist’s work or and exhibition. You can tease images before a show opens or reveal behind-the-scenes studio visit photographs to help build momentum for an artist’s audience.

Galleries and artists have been able to use social media to sell work, too. Instagram allows your program to have a “personality.” We recommend having fun with it if you’re a smaller/younger enterprise. Bigger galleries may take a more professional approach, using only high-resolution retouched images and consistently posting at specific intervals. Either approach can work well; it simply depends on your gallery mode and identity. With your artists’ use of Instagram, it is important to discuss guidelines as to what is productive or perhaps counterproductive to post. For example, say you have a waiting list for an artist’s work and they post new images; both you and the artist could be bombarded with interest and difficulty in navigating who is next in line. Additionally, before an exhibition, you may not want specific details about the show revealed, especially if you’ve pitched an exclusive to a press outlet or promised specific works to clients. Just the right amount of information can, however, be a motivating and buzz-building tool before an exhibition opens.

EDITORIAL

As mentioned earlier, many of the e-commerce sites offer editorial platforms. With print media becoming tougher and tougher to profitably produce, many magazines are moving online. What this means is more real-time coverage of an exhibition. You should do your research among the major sites: Artnews, Artnet news, Artspace magazine, Hyperallergic, Artsy magazine, Cultured, and Artforum, to name a few, and see which writers are regularly writing about exhibitions near you. As most of these writers are freelance, you should feel free to reach out to them directly inviting them to a show or an artist’s studio; they may have multiple outlets they can pitch to.

ALTERNATIVE FUNDING MODELS

This area will likely be the most interesting to watch over the next five to ten years. Websites like Kickstarter and Patreon offer new forms of support for creative communities and seek to redefine notions of patronage. Kickstarter was founded in 2009 by three creative individuals—an artist, a musician, and a designer—with the intent of solely supporting creative projects. They coined the term crowdfunding and helped to train a community to understand how anyone can be a patron for micro amounts of money, democratizing the funding process, while simultaneously creating new access and excitement around creative endeavors. To date, Kickstarter has funded over $82.37 million in arts projects alone, and it’s growing. It has quickly grown in the arts community with artists, galleries, and curatorial practices all creating projects to share with their respective communities. Kickstarter serves not only as a funding tool but as a marketing a promotional effort too in this regard. It is an excellent option if you’re looking to raise attention and funds around a project that may not always be the most commercially viable exhibition or artists; however, the work is important and relevant.

Patreon is also changing this landscape through ongoing sustained funding for creative individuals. It began in 2013 and has grown rapidly within in the podcast and gaming community; however, it is used by several artists and arts organizations as a way to provide ongoing interaction with their communities. In turn for a micro pledge amount of money on a monthly basis, the artist/organization will give their subscriber a piece of exclusive content. While the arts interaction on Patreon is significantly lower than say, Kickstarter, as artists, artist collective spaces, and new gallery models appear, the site may be able to offer a way to garner guaranteed monthly income. In fact, at the time of this writing, Kickstarter has recently launched a similar monthly subscription service called Drip. Though it is still in a public beta phase, the majority of creators on it are artists and art organizations. It will be interesting to see how this platform grows. Crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Patreon offer the opportunity for a gallery and artist to explore ideas outside of the mainstream market model. They have the chance to reshape how the art world exists now and expand galleries’ and organizations’ ideas of patronage in a substantial way, especially as organizations look to increase their audiences.

LESSONS LEARNED

The Internet has dramatically reshaped the art world, calling for greater transparency with pricing but also delivering access to artists, dealers, and their communities in a new and exciting way—breaking down the old guard of the removed dealer. Having lived and worked through this significant transformation, we urge you to both be open to new models but also to take all of your options seriously, be it selling online or running a crowdfunding campaign. Each of these decisions has the opportunity to affect your core business and make you more accessible but also should be taken with a grain of salt. They will never be a cure-all; rather, they will most likely simply supplement the core activities of your business.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Art Has Always Been About the Cash: Money, Medicis, and Modernity

ART MARKET

Art Has Always Been About the Cash, You Weirdos: Money, Medicis, and Modernity

By Torey Akers

JUNE 6, 2019

Since Trump became our President back in the dark, punishing November of 2016, the art world has been playing a cringey game of catch-up as it attempts to ascertain what role it played or didn’t play in this particular cultural degradation. To a greater extent, creatives have been forced in the intervening years to grapple with the reach of visual protest under late capitalist neoliberalism—what change can a painting or sculpture really effect, anyway? A new brand of incisive ‘wokeness’ is starting to bubble to the surface of artspeak, however, one that requires authentic interrogation. At the foundation of this treatment lies a “follow the money” ethos, which has led to a variety of high-profile comeuppances for ultra-rich art benefactors. Just ask Warren Kanders, or the Sackler family, not that they’ve experienced any financial hardship as part of the pushback to their, uh, crimes against humanity. Still, is it all too little, too late? Or, perhaps more insidiously, does this new breed of moralizing revulsion amount to a well-intentioned but deeply willful misunderstanding of art history?

Christie's market floor via Christie's

Christie's market floor via Christie's

In an unfocused, self-aggrandizing 2018 essay for Vulture, Roberta Smith’s husband reviewed the art market documentary The Price of Everything through the lens of his own rarified Aspen dinner party interactions. After half-heartedly calling out a super-collector for voting Republican (a billionaire? Voting conservative? Shocking.) Mr. Roberta Smith recounted, “Down the table, meanwhile, it got worse. A woman married to one of the world’s largest machine-gun manufacturers babbled about being adamantly against any kind of gun control. The three artists present, two gallerists and I were astonished and began arguing with this the group... but they all gawked at us like we were just dumb clucks who should shut up and stick to art.” Later, he opined, “Probably more than half of all current collectors, advisors, auction people, and others in the art world are Republican. And voted for Trump”.

Which...yeah. Of course.

The Sackler wing of the Met via Art Newspaper

The Sackler wing of the Met via Art Newspaper

Why is it surprising that a woman whose fortune relies on the sale of AK-47s is an NRA member, and why is no one asking how she got at that table in the first place? Maybe because art is and has always been a luxury flex, a tool of the state, and a roundabout method of accrual exploited by the the power-hungry and ladder-climbing du jour. None of this is news. Even renaissance masterpieces were commissioned directly by the church or members of the nobility. In her book, Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, Georgina Adam tracks the modern painting trade back to 17th century Dutch Republic, where the absence of monarchical or church patronage created a domestic genre painting open market. In the early 20th century, she further notes, Baron Joseph Duveen made a huge amount of money selling Old Master works he plucked from broke European aristocrats to American industrialists. The economic liberalization of China and India in the late twentieth century in confluence with the fall of communism in Eastern Europe gave rise not only to new, expanded markets, but also to a glut of private museums, which functioned not just as status symbols, but state-approved means for lucrative real estate development. It’s notable that Christie’s auction house was purchased in 1998 by the owner of luxury retail conglomerate Kering, whose lineup includes Gucci and Balenciaga. Cut to 2019, where Jeff Koons bunnies are selling for 90 million dollars a pop. This is a through-line, not a departure.

Jeff Koons' "Bunny" 1986 via Forbes

Jeff Koons' "Bunny" 1986 via Forbes

As such, the notion that art is a necessary public good in danger of corruption by financial black magic feels a little reductive. With this in mind, it seems useful to revisit the rise of the Medici dynasty, the 15th century banking family who were effectively responsible for both monopolizing and transforming Florence into the art and commerce center of the Western world for nearly three hundred years.

Medici Palace via VisitTuscany

Medici Palace via VisitTuscany

In the middle of the fifteenth-century Florence, the Medici were at the height of their influence, lead by the visionary Cosimo, who had risen from relative Tuscan obscurity to a business magnate with matrimonial ties to the seated Pope. After his death in 1494, he was hailed by the Florentines as Pater Patriae, or Father of the Country, an identity that was bolstered by literally palatial displays of wealth. He was also responsible for connecting the family to the lay confraternity of the Compagnia de’Magi, a social club of well-to-do Florentines who fashioned their acts of social philanthropy after the three kings, a configuration that inspired one of the Medicis' first acts of artistic propaganda. Either Cosimo or his son, Piero, commissioned a circular panel of the storied Magi adoration by Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi, an explicit depiction of the family as benevolent religious figures destined for greatness. This heavy-handed allegorical infusion of personal narrative with showpieces fast became a family tradition. Take Lorenzo de’Medici’s childbirth tray depicting Petrarch’s Triumph of Fame, or Lorenzo’s eventual placement of idealized portraits in the opulent Florentine cathedral he bankrolled.

Fresco Cycle , Magi Chapel via Love From Tuscany

Fresco Cycle , Magi Chapel via Love From Tuscany

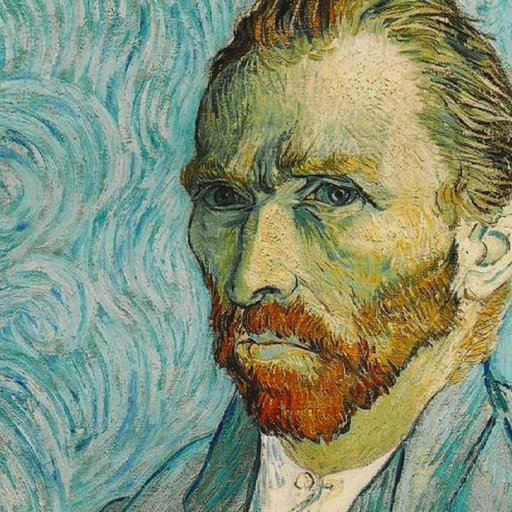

Medals, coins, outdoor statues, and fountains were created ad nauseum in the Medici family image, flooding every imaginable public space in the city. Michelangelo and Botticelli regularly stayed with the family, essentially rendering them in-house talent. Lorenzo, otherwise known as Il Magnifico, (subtle) often used art as a means of promoting foreign policy; bronze reliefs of Alexander the Great and Darius, King of Persia, were sent to then-King of Hungary Matthias Corvinus in hopes of furthering a political alliance. In 1513, Lorenzo’s son, Giovanni de’Medici, became Pope Leo X, stationing the Medici line at the heart of Western culture, a position that amplified an already ostentatious relationship with art patronage. Enter pieces like the foot-washing earthenware bowls depicting the Medicis as gods, or the de’Rossi Sardonyx cameo displaying the Medicis' 'conquering hero' allure.

Lady in Red by Bronzino, 1525 via IrishTimes

Lady in Red by Bronzino, 1525 via IrishTimes

The Medici patronage tradition reached a crescendo in the practices of Cosimo I, the first member of the Medici family to be crowned a Duke. His ascendancy to the rule of Florence in 1537 oversaw some of the most heavy-duty implementation of allegory of the era, like an outdoor cameo featuring Cosimo I and his wife, Eleonora, gazing up at a trumpeting goddess of Fame floating overhead. The cameo is a distinct reference to Imperial Roman frontispieces, making its subtext all the more clear. Cosimo I was not just a duke, but a deity, a supreme leader, and a demigod. The Medicis owned Florence, and their art patronage helped relay the message to any member of the citizenry with functioning eyeballs. In an era where literacy was a privilege few could afford, religious or mythological messaging was not only an essential tool, but an indispensable means of hegemonic consolidation. Parisian curator Nicolas Sainte Fare Garnot has noted, "The Medici needed images, particularly portraits, to establish their power. They used portraits as a propaganda weapon." And weapons, by the way, were a huge part of why the Medicis thrived; in the two brief periods (1492-1513 and 1527-1530, respectively) where Medici rule was interrupted by mutinous troops, it was a series of calculated usurpations and assassinations that placed family members back at the figurative helm.

Medici Medals via Italian Renaissance Learning Resources

Medici Medals via Italian Renaissance Learning Resources

Suffice it to say, it was a Medici who created the proportional model for taxation, despite not holding any official political office at the time. It was a Medici who transformed the way lending, spending, and government involvement in banking functioned. The modern monetary system bloomed not just alongside artistic agglomeration, but directly because of the social capital it afforded those willing to utilize creative production for clout. In summation: Renaissance art was not merely an arbitrarily gorgeous collective outpouring of humanist ethos, it was a project of power, one that created a blueprint for our current deregulated, increasingly criminal art market climate. It's always been about the money, and the money has always been the symptom of larger, interconnected lapses in social ethics. Our role in dismantling these models begs to be tested.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Art Collectors Who Gave Up Pieces that Would Have Made Millions

ART MARKET

Should, Coulda, Woulda: 8 Art Collectors Who Gave Up Pieces that Would Have Made Millions

By Colleen Hochberger

AUG. 3, 2019

No one wants to be on the recieving end of "shoulda, coulda, woulda," and yet, we all have regrets. Some, however, are more costly than others. In an art market where hundreds of millions of dollars can exchange hands at the drop of a hammer, missed opportunities abound. Take collectors Robbi and Bruce E. Toll, who revealed in an ARTnews article that they regretted selling a large Pissarro roughly 30 years ago for around $100,000. If they still had it today, it would be worth approximately $5 million.

We’ve compiled a short list of our favorite moments—some laughable, others cringe-worthy, and one extremely refreshing—where collectors unknowingly (or actively) let millions slip away.

Richard Polsky

I Sold Andy Warhol (Too Soon), 2009

I Sold Andy Warhol (Too Soon), 2009

Photo of Richard Polsky with Andy Warhol. Image via artnetNews

Photo of Richard Polsky with Andy Warhol. Image via artnetNews

In his tell-all memoir, author and private art dealer Richard Polsky writes about the 2005 sale of his cherished Andy Warhol Self-Portrait with Fright Wig. At the time, the market was robust, and his attempt to turn a profit proved successful when he sold the piece for $375,000. Unfortunately, Polsky couldn’t foresee the mindboggling prices the Warhol market would fetch over the next few years; had he waited to sell, he surely would have made millions (in a 2016 Sotheby’s contemporary art evening auction, a Warhol "Fright Wig" sold for $7,698,000). I Sold Andy Warhol (Too Soon) is Polsky’s memoir, but it's also an analysis of a pivotal era when he claims the “art world” became the “art market,” as the industry shifted its focus from art to money.

Lisanne Skyler

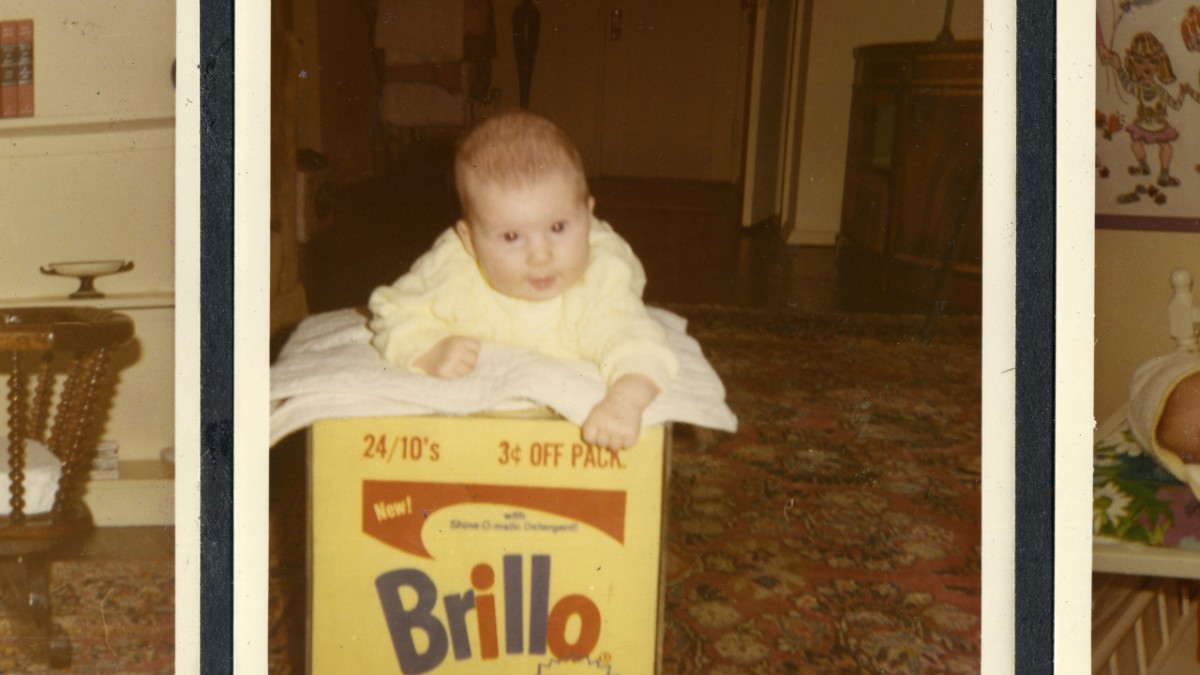

Brillo Box (3¢ Off), 2016

Brillo Box (3¢ Off), 2016

Image via HBO

Image via HBO

Another Warhol piece that got away too soon belonged to the parents of writer and director Lisanne Skyler. The piece was one of his renowned Brillo Box (3¢ Off) sculptures—replicas of the shipping carton for Brillo soap pads. In 1969 the couple purchased the yellow sculpture for $1,000. The box lived in the family’s living room (inside Plexiglas to prevent damage) for two years, before her father decided to trade the artwork for a drawing by abstract artist Peter Young. Forty years later, Skyler learned that her family’s once beloved Brillo Box was going to be auctioned in New York at Christie’s. She decided to make a film out of it by combining archival video, interviews with her parents and contemporary art world figures, and footage of the record-breaking Christie’s auction to reconstruct her family’s Brillo Box history. Spoiler alert: it ended up selling for more than $3 million.

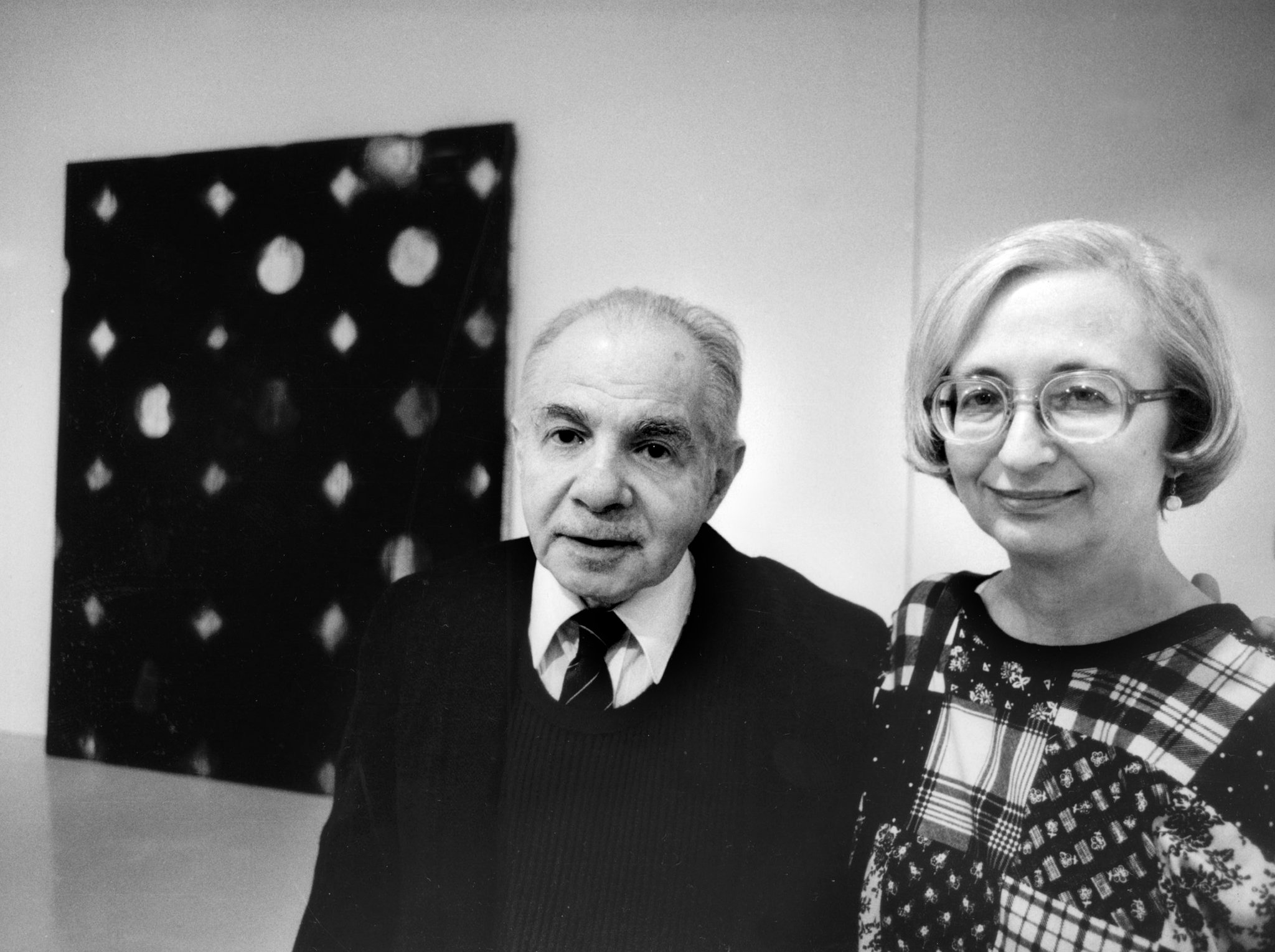

Dorothy and Herbert Vogel

Their entire collection, 1992

Their entire collection, 1992

Image via the New York Times

Image via the New York Times

Speaking of great art world documentaries, Herb and Dorothy (2008) is a must-see. The film, made by Megumi Sasaki, tells the exceptional story of the Vogels, an unassuming, working-class couple who inconspicuously amassed one of the greatest post-1960s art collections in the United States. Herb, a clerk for the post office in Manhattan, and Dorothy, a reference librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library, had an extreme passion and serious eye for art. Befriending emerging artists at the time, like Christo and Jean-Claude, and carrying home the affordable work purchased via taxi or subway to store in their rent-controlled studio apartment, the couple eventually accumulated over 4,782 works.

Focusing mainly on conceptual and minimalist art, their collection includes art from Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Mangold, Richard Tuttle, Sol LeWitt, Lorna Simpson and more. And the best part—they never sold a thing. Instead, in 1992 they donated their entire collection to the National Gallery of Art since it charges no admission and doesn’t sell donated works, essentially gifting their collection to the public. Herb told the Associated Press, “We could easily have become millionaires. We could have sold things and lived in Nice and still had some left over. But we weren’t concerned about that aspect.” If only there were more legendary couples like the Vogels in the art world...

Yvonne Force Villareal

Takashi Murakami’s Miss ko2, 1997

Takashi Murakami’s Miss ko2, 1997

Image via Christie's

Image via Christie's

Co-founder of the Art Production Fund, Yvonne Force Villareal’s chance to potentially make a lot of money was hanging by a thread—or in this case, a nylon string. In 1997, Takashi Murakami’s Miss ko2 was exhibited in New York City’s Feature Gallery and Villareal fell in love. The collector told Blouin Artinfo that she was about to purchase the life-sized sculpture for $25,000, but hesitated after noticing a thin nylon string fixing the sculpture to the gallery’s ceiling. The string completely shifted her perception of the piece, and she ultimately chose not to buy Miss ko2. Since then, Murakami’s work has seriously blown up, in both value and hype. In a 2003 Christie’s evening sale, the same sculpture sold for $567,500. While Villareal doesn’t want to let the regret get to her, she does question her decision of not purchasing the work based solely on the string.

Nye & Company

Rembrandt’s The Unconscious Patient (An Allegory of Smell), 1624 or 1625

Rembrandt’s The Unconscious Patient (An Allegory of Smell), 1624 or 1625

Image via the Leiden Collection

Image via the Leiden Collection

After a couple in New Jersey passed away, their adult children hired Nye & Co., an auction house in Bloomfield, New Jersey, to assess their late parents’ property for valuables. Among furniture, silver, and many artworks, there was a rather unremarkable painting (whose surface was flaking) depicting an unconscious man being revived by what look like smelling salts. In a September 2015 auction sale, the work received far more than Nye & Co. anticipated when Paris art dealers immediately suspected that the painting was a long-lost Rembrandt, as it had similarities to other paintings in the artist’s five-sense series. The Paris art dealers, who bought the work for around $1 million, later turned around and sold the piece to Dutch Golden Age art collector Thomas Kaplan for a reported $3 million to $4 million. Too bad Nye & Co. (or the deceased homeowners’ children) didn’t realize what they had on their hands.

Phoebe Chason

Basquiat’s Untitled, 1982

Basquiat’s Untitled, 1982

Image via the New Yorker

Image via the New Yorker

Art collector Phoebe Chason purchased Untitled by Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1982 from New York’s Annina Nosei Gallery for $5,000. Later that year, she sold the piece to Alexander F. Milliken, and it was sold in auction in 1984 for $19,000. The large-scale painting, depicting a colorful skull-like head in Basquiat’s iconic graffiti style, would become a paragon of the artist’s legacy. Just 35 years later, in 2017 (29 years after the artist’s premature death), Untitled became the most expensive American artwork ever sold at auction, selling at Sotheby’s for $110.5 million. Ms. Nosei, who attended the auction and originally sold Chason the piece, told the New York Times, “I never understood money. If the market says that’s what the painting is worth now, that’s what it’s worth.” Hindsight is obviously 20/20, but Untitled probably would have been a good artwork for Chason to hold onto for a few more decades.

Poul Rée

Portrait of Eva Mudocci attributed to Edvard Munch, 1903-1904

Portrait of Eva Mudocci attributed to Edvard Munch, 1903-1904

Image via artnetNews

Image via artnetNews

St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota is quite confident that they have a long-lost Edvard Munch painting on their hands, and a recent discovery of the painting’s provenance and a scientific analysis of the painting’s materials largely support this claim. Richard Tetlie, a 1943 graduate of the college, donated the painting (thought to be a portrait of the violinist Eva Mudocci) to the school’s Flaten Art Museum in 1999. But it wasn’t until Mudocci scholar Rima Shore was researching for her new book Lady With a Brooch: Violinist Eva Mudocci—A Biography and a Detective Story that the author found letters to and from Munch referencing him painting her around this time. Shore also found an auction record from 1959 showing that Poul Rée purchased the work from a close friend of Mudocci’s. Rée then sold the work to Tetlie for $10,000—declining to have it authenticated by a prominent Munch dealer who offered to, as seen in another letter Shore dug up. Perhaps if Rée chose to have the painting authenticated he would have kept it and sold if for a lot more later on. According to artnet, another one of Munch’s paintings of Mudocci, The Brooch: Eva Mudocci, sold at auction for $288,166 in 2014.

Steve Wynn

Pablo Picasso’s Le Rêve (1932) and Le Marin (1943)

Pablo Picasso’s Le Rêve (1932) and Le Marin (1943)

Pablo Picasso's Le Marin (1943). Image via Fortune

Pablo Picasso's Le Marin (1943). Image via Fortune

Damage your Picasso once, shame on you. Damage your Picasso twice, shame on you? In 2006, luxury casino and hotel magnate Steve Wynn (who in February 2018 resigned as chairman and chief executive of Wynn Resorts due to allegations of sexual misconduct) accidentally put his elbow through the canvas of the Picasso masterpiece he owned, Le Rêve, just before he was contracted to sell it to hedge fund collector Steve Cohen for $135 million. While Wynn temporarily missed out on a serious payday—due to what the New Yorker referred to as the “$40-million elbow”—he eventually had the painting restored and sold it to Cohen in 2013 for $155 million (so I guess in this case it was ultimately Steve Cohen who lost millions). But, unbelievably, this past year Wynn had another Picasso upset when Christie’s—who was set to auction off another Picasso he owned, Le Marin, valued at $70 million—accidentally damaged the work with a metal rod that fell on the work, creating a hole in the canvas. Somehow, I still feel like this one was Wynn’s fault too (or maybe he just deserved it? See above regarding sexual misconduct). I’m sure he’ll get millions from his Picasso eventually; you know what they say—third time’s a charm!

RELATED ARTICLES:

RELATED ARTICLES

ART MARKET

ART MARKET

ART MARKET

CURRENT SHOWS

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)