How to Take a Portrait, According to Photographer Catherine Opie

Catherine Opie, Self portrait/Cutting, 1993. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Self portrait/Cutting, 1993. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Catherine Opie, Justin Bond, 1993. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Justin Bond, 1993. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

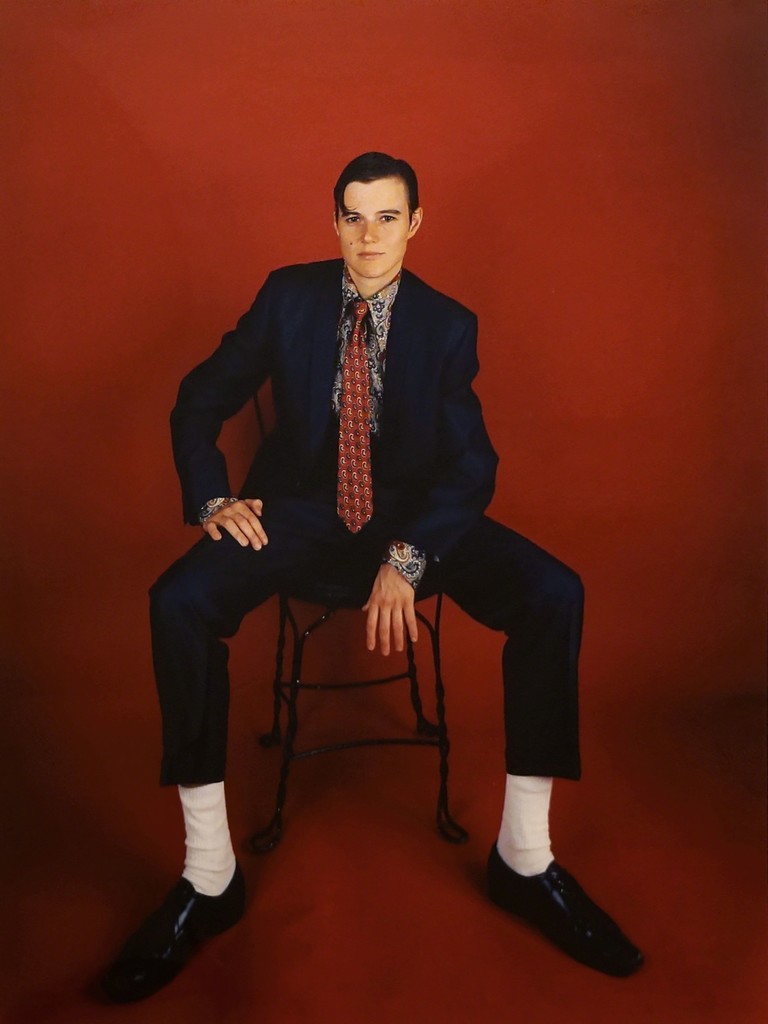

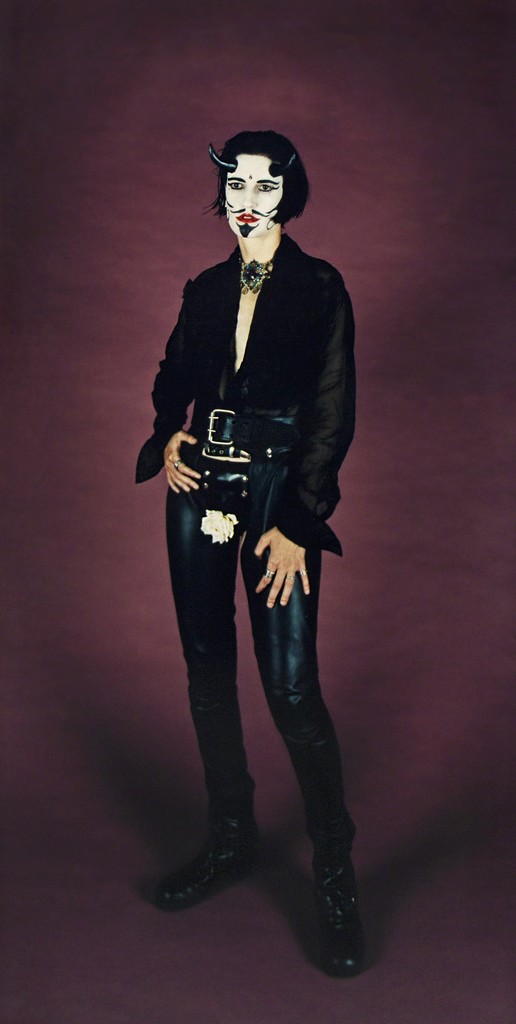

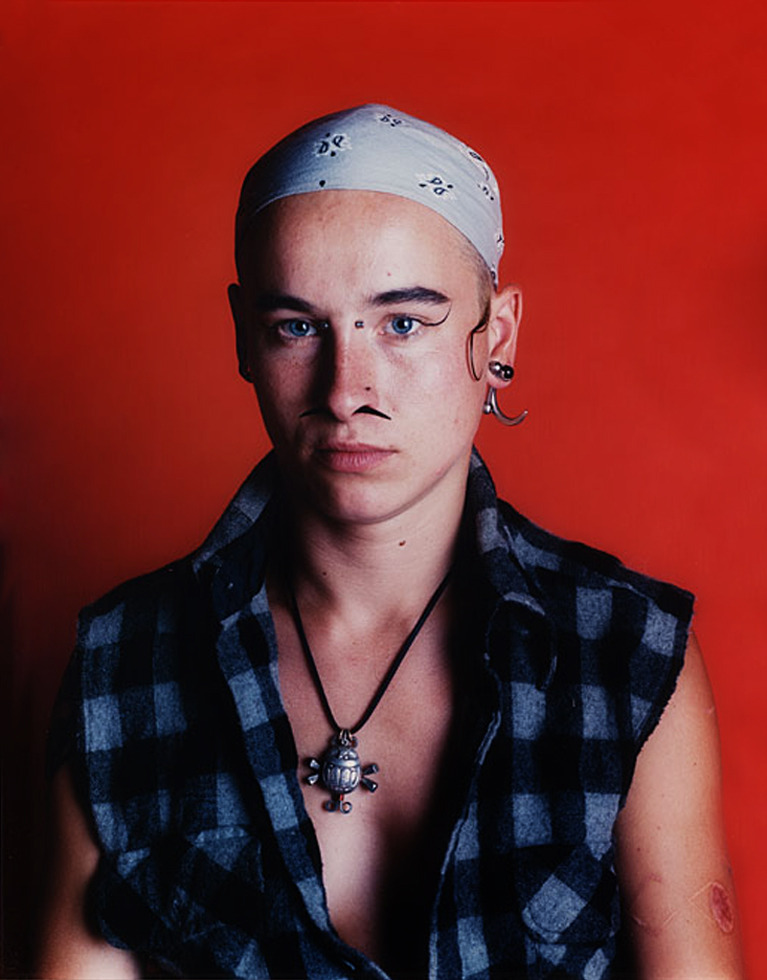

As one of the leading fine art photographers working in the United States today, Catherine Opie has earned acclaim and attention for her portraits. For over 30 years, she’s taken photographs of herself, and of others—from the queer and S&M communities of Los Angeles and San Francisco, to surfers, high school football players, and fellow artists, like Kara Walker, Mary Kelly, and Glenn Ligon. Known for her contemporary take on a formal, classical style, Opie has recently looked to canonical Baroque and Old Master paintings for inspiration.

Now based in Los Angeles, Opie has served as a professor of photography at UCLA since 2001, and previously taught at the Yale School of Art, all the while sharing her mastery of the medium with younger generations of photographers.

As she unveiled a new series of portraits at Thomas Dane Gallery in London, we caught up with Opie, who shared the lessons she’s honed over the years, on how to photograph a portrait.

Have a question to answer

Catherine Opie, Nicola, 2014. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Nicola, 2014. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Catherine Opie, Thelma & Duro, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Thelma & Duro, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

“The most important thing to do is to begin with an idea that tries to answer some questions,” Opie explains.

With her most recent series of portraits—of subjects including David Hockney, Anish Kapoor, Gillian Wearing, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Thelma Golden, and Duro Olowu, most of which were taken in London—she considered portraiture through history, from Old Master paintings to selfie culture, and sought to answer age-old questions around representation. “I’m trying to re-calibrate portraiture to an extent,” she explains. “What is it to stare and be stared at? I’m trying to approach that question through this body of work.”

At a time when portraits—celebrity portraits in particular—are ubiquitous, Opie emphasizes that asking critical questions before shooting is essential. “I started to think a lot about selfies in this day and age, where everything is photographed, and what it means to hold a person with an image now,” she notes.

“History holds us in some way, but what is it to be a contemporary artist and bump up against history by using an aesthetic of Old Master paintings within portraiture?” she asks. “Does it allow you to enter a subject in a different way? Even though the portrait is contemporary, it creates history, and photography has always operated very well on that level.”

Don’t force it

Catherine Opie, Jonathan, 2012. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Jonathan, 2012. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Catherine Opie, Michele, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Michele, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

When it comes to organizing and executing shoots, Opie has found that it’s best not to force her subjects into certain scenarios or emotions.

This begins with who she can and cannot shoot. “There’s always someone I want to photograph who I can’t get,” she admits, noting that she’s been trying to shoot a portrait of Joan Didion for 10 years; and for the portraits in London, she’d wanted to shoot Sarah Lucas, but it wasn’t possible.

Once a shoot is confirmed, Opie is careful to prepare her subjects, but not to give them too much direction. Beforehand, “I say it’s a formal portrait,” she explains, “but I don’t tell them how to dress.”

The day of the shoot, when the subject arrives at Opie’s studio, she offers them a beverage (“a coffee, or whatever”) and they sit down for a chat. “If they have the time to spend, if they’re not on a time crunch, we might talk for 30 minutes or so,” she says. “If it’s the first time meeting me, I want them to know and feel that the portrait is just a conversation, I’m not essentialist about my ideas—I care deeply about what I’m doing, but I’m not manipulative about wanting my subject to show a certain emotion.”

To accomplish this, Opie ensures that the atmosphere in the studio is as calm and neutral as possible. This is important not only in making her subjects feel at ease, but also to make sure that the resulting photographs (particularly her most recent series, shot over the last five years) do not aim to expose the essence of a person, but rather seek to create an intimate moment in time that speaks of the power of a portrait.

This also accounts for why Opie chooses not to play music, and speaks little during shoots. “Music informs a potential emotion. If you play jazz, and the subject hates jazz, you’re screwed,” she explains. “I’m very quiet about it all, I want them to create an internal space.”

The black backdrops Opie has chosen for her recent works are also a part of this neutral space. “The black background is also blank,” she says, “everyone is placed by me, it’s a controlled environment but it’s not a manipulative environment.”

Shapes are important

Catherine Opie, Kayla & Owen, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Kayla & Owen, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Opie’s only concession in her minimalist set-up is chairs. “I always have different chairs,” she explains. “Some portrait photographers have one chair, but I prefer different chairs because I want to have different shapes—shapes are really important to me.” Shapes are also crucial to her decisions around lighting and shadow.

“Lighting is a way of creating shapes as well,” Opie notes, “so when I’m casting a shadow or illuminating certain things, dealing with this black, absorbent background, I have to allow the light to wrap on the body and be specific in the placement, as there’s no shadow except on the figure.”

Shadow is a major contributing factor to Opie’s style; she uses shadow create interest, to stop the viewer and make them slow down. “I want to get to this place where I can give the viewer the chance to gaze at something with longing,” she says. “I think we need longing, we want to be held, we’re moving way too fast. Art is becoming a selfie moment—you wait in line to see a Kusama exhibition to take a selfie. These aren’t selfie moments. They’re designed for you to have some intimacy.”

Highlight the details

Catherine Opie, David, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, David, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Catherine Opie, Celia, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Celia, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

In Opie’s recent portrait of David Hockney, small yet crisp details, like a smudge of paint on his trousers and the hearing aid tucked behind his ear, serve to help us connect with the legendary artist. Understated gestures are similarly powerful in the double portrait of Studio Museum in Harlem director Thelma Golden and her husband, fashion designer Duro Olowu. In this case, it’s Golden’s hand gently resting on Oluwu’s, and a smile that pulls at the corners of her mouth.

Through details like these, Opie is able to reveal a sense of intimacy and vulnerability, and the humanity of her subjects above all. “Subtle things tell a larger story if you’re paying attention to those details,” she says. During a shoot, she says, she directs every micro-gesture, until the pose is exactly right.

“I think I’ve always been observing people,” she offers. “I’m always told I’m staring way too much!”

Be thoughtful and responsible

When her early works like Self Portrait/Pervert (1994) exploded in the ’90s, the artist’s own body was the center of attention; people saw the photographs and made assumptions about Opie as a person. “People I’d meet would tell me, I was really scared of you, but you’re actually really nice!” she recalls. That personal experience has contributed to the thoughtful approach she takes to capturing the likenesses of others.

“My line is no humiliation,” Opie explains. “Anyone can feel exploited to an extent, even if they’ve given permission. It’s about having incredibly clear parameters in relationship to why you’re making bodies of work.

“The biggest problem now is people’s fear of how the work is going to be represented, instead of trying to follow some kind of quandary and working hard to create bodies of work around ideas of representation,” she continues. “People are messy, especially now. Be thoughtful and responsible about it.”

This often comes naturally, though, as Opie often works with friends, acquaintances and fellow artists—people with whom she shares mutual trust. “Everyone who sits for me knows they’re giving me their permission to use the image,” she acknowledges. But even when consent is clear, she warns that subjects won’t always like the results. “It’s important to me that my subjects like their portrait, but most don’t,” she offers.

“You need to remain true to yourself and your ideas as an artist, and live with other people’s perceptions and expectations of you as a person,” she says. “If you get to be an artist and produce work for your whole life, it’s incredibly brave.”

Trust your intuition

Catherine Opie, Lynette, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Lynette, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Catherine Opie, Gillian, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, Gillian, 2017. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

During a typical shoot, Opie takes between 30 and 40 shots of her subject, from different angles and distances. But how does she know if a portrait is good? “I go through really quickly and hang it all on the studio walls and I live with it,” she explains. “I come in every day and ask if it’s holding me and if I still want to look at it. If I don’t, I go back to the contact sheets. Then, I start to think about the body of work together.”

This bleeds into her approach to editing. “If you look at a picture and you know that’s the one you want to be with, let that guide you. Editing for me is really quick,” she says. “I always tell my students, ‘Edit really fast. Don’t overthink it. Do it from a gut place.’ That sounds ridiculous, to an extent, but hopefully you already have a conceptual framework, in relation to those questions you’re trying to ask.”

Consider the portrait in physical space

Catherine Opie, David, Austin and Bryant, 2009. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Catherine Opie, David, Austin and Bryant, 2009. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Rather than shooting portraits knowing that they’ll end up on social media, Opie says she still thinks it best to consider the viewer’s physical encounter with a photograph as the best way of seeing them. “I still say you have to see work in person—and think about that first,” she explains.

“At this point, we’re flipping through images all time, so if you want to create an experience, the architecture has to have a relationship to what you want to put in the gallery space,” she advises. “The digital space is like magazine space—it’s having your work live on past the exhibition. But ideally most people want to go and look at work and you need to think about the scale of your pieces, and scale in relation to the space you’re hanging the work.”

—Charlotte Jansen