What Makes a Movie Artsy? A Beginner’s Guide to Understanding What Separates "Blue Velvet" from "Blue Crush"

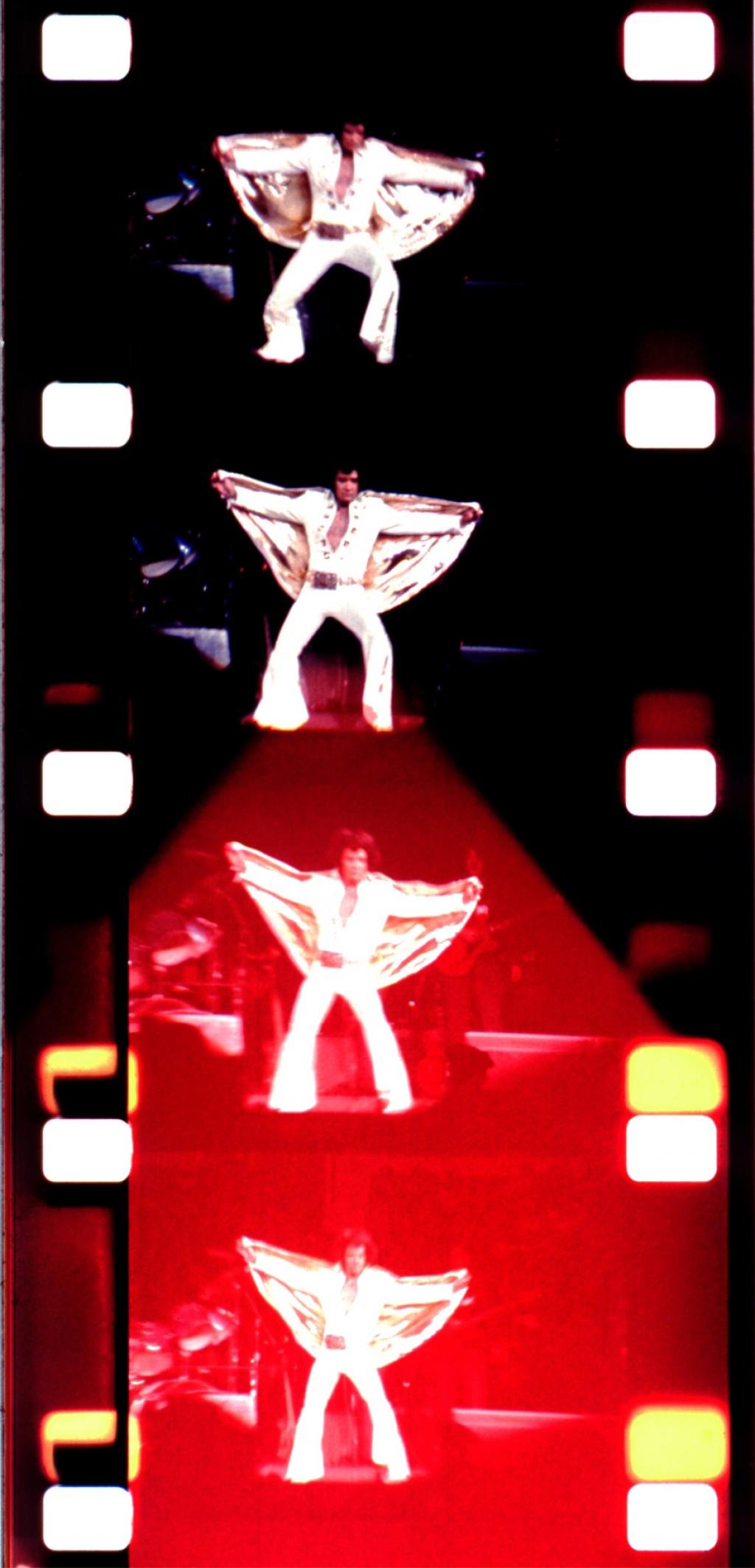

If you were shocked when MoMA added Harmony Korine’s feature film Spring Breakers (2013) to its permanent collection because you felt like the fleshy thriller was nothing more than James Franco waving a gun around, you’re not alone. While some hailed the film’s social commentary “genius,” many couldn’t figure out what Spring Breakers was trying to say—evident in the polarized Metacritic reviews.

Still from Harmony Korine's Spring Breakers (2013). Image via Vulture.

Still from Harmony Korine's Spring Breakers (2013). Image via Vulture.

What makes a film, for lack of a better term, "artsy" isn't easily defined. Somewhere on a spectrum between blockbuster action flicks on one end and Nam June Paik video art installations on the other, "artsy" films are typically independently produced, premiered and judged in festivals like Cannes or Sundance, and screened in select art house theaters. Because independent (or "indie") films typically entertain a niche audience, their producers can assume they won't be the cash cows that Hollywood-produced mainstream movies are. Instead, operating on shoe-string budgets, indie films often tap emerging talent rather than expensive big-name celebs, avoid CGI and special effects, and keep set locations to a minimum. Indie films rely on captivating their audiences through their "artsy" storytelling techniques. But what are those techniques, you ask? Here are a few:

Narrative Structure

Conventional films generally have a straightforward, cause-and-effect style plots that follow a standard formula: a set-up that sets the stage and introduces the lead, an opportunity for the main character that motivates them to take a certain course of action, a conflict or complication that poses a problem and raises the stakes, the climax wherein the character realizes her goal, and the final aftermath that reinforces a feeling of satisfaction and completion.

Conversely, artsy or experimental films typically go out of their way to break the formula to create more unexpected narratives. These narratives are not always linear (think Christopher Nolan's Memento), or they may follow multiple storylines and characters simultaneously. For example, Japanese film director Akira Kurosawa—who’s revered as one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of cinema—won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival for his debut film Rashomon (1950) that examined the nature of truth and justice through telling a story from multiple perspectives. This film created a groundbreaking narrative device now known as “The Rashomon Effect,” which many films continue to implement. (Fun fact: Kurosawa was actually a painter before entering the film industry, and he storyboarded his films as full-scale paintings.) A more contemporary example of a non-linear film is Terrence Malick's Tree of Life (2011), which one the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Staring Sean Penn, Brad Pitt, and Jessica Chastain, the story is told via flashbacks, punctuated by long scenes devoid of any and all characters or plot developments.

Akira Kurosawa. Image via bfi.org.uk

Akira Kurosawa. Image via bfi.org.uk

Cinematography

Cinematography, or the art of motion-picture photography, is one of the most powerful elements in movie making. Great cinematography doesn’t necessarily record reality as is. Instead, it visually interprets the scene to help communicate mood. Camera angles, movement, composition, lighting, and color are all aspects of cinematography that work together to create a cohesive look and feel.

While conventional films are now typically shot via digital video due to it's relative low cost compared to film, some indie films splurge on using real film, which can pick up a broader spectrum of light than video, meaning colors are richer and scenes with large contrasts in lighting can be quite detailed. For the 2018 film Suspiria, cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom used 35mm film stock and a Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 camera without correction filters. Basically, in laymen's terms, this means that the resulting film felt like a '70s film, further emphasized by Mukdeeprom's use of slow zooms (typical of the time period), and dark, gray, "winterish" color pallets. The result is an atmosphere that is eerie, chilling, and unsettling—exactly what the filmmakers wanted given the film is a supernatural horror piece set in Berlin on the verge of a civil war in 1977.

Still from Suspiria (2018). Image via Bloody Disgusting.

Still from Suspiria (2018). Image via Bloody Disgusting.

Editing

Film editing happens post-production, meaning after the movie has been filmed. The editor is responsible for the pacing of the film, and combines the visuals, dialogue, and soundtrack into a cohesive piece. It's often said that "good" editing is editing that you don't notice; in other words, it's seamless and doesn't distract the viewer from the world it's building on screen. On the other hand, experimenting with how a film is cut can be used to intentionally draw the viewer's attention to how the film is made. The 1959 film Breathless, by French New Wave godfather Jean-Luc Godard, is cited in film theory 101 classes across the globe as an innovator in editing. The use of jump cuts, wherein two sequential shots of the same subject are taken from camera positions that vary only slightly if at all, intentionally induce a feeling of unease or discomfort within the viewer, who is forced to acknowledge the cinematic devices used to manipulate her. (Read up on Godard here.)

Sound

Another key category in film is sound mixing and editing. Most of the sounds you hear in a film are created in a studio by technicians. The 2018 film A Quiet Place heightened tension throughout the movie by creating an almost completely silent film where any slight noise was detrimental to the cast. Films can also create artistic juxtaposition through sound that can become iconic—like in Apocalypse Now (1979) when Richard Wagner's classical song "Ride of the Valkyries" blasts in the background during a war-torn scene.

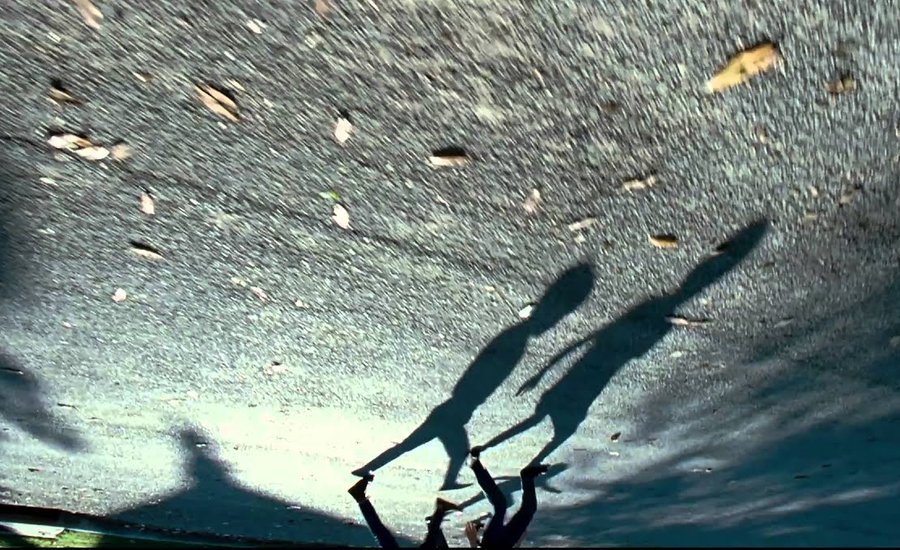

While many art films possess the above qualities, there ultimately isn’t a clear-cut checklist to distinguish what makes a film a true work of art, because at the end of the day, art is subjective and its definition is ever changing. When Andy Warhol’s film Blue Movie (1969) was initially released, the audience reception was highly controversial. The movie was the first widely released film to explicitly depict sexual intercourse, and many labeled the film pornography. The staff of the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theatre was even arrested for showing the film in 1969. Today, the film elicits an extremely different reaction, and in 2016 Blue Movie was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art, a space that culturally confirms the film's artistic standing. Evidently, art films are not highbrow works entirely removed from popular culture, and blurring the line between “high” and “low” culture was something that Warhol was far too good at.

Also like art, many of the themes and movements in film overlap with art history. Movies can be abstract, postmodern, camp, realist, surrealist and more. The surrealist master Salvador Dalí even made movies. He co-directed the 1929 silent surrealist short film Un Chien Andalou and later wrote the surrealist film L’Age d’Or (1930). Other notable film movements that defined cinema include French Impressionism (1918–1930), German Expressionism (1919–1926), Italian Neorealism (1942–1951), and British New Wave (late 1950s – late 1960s).

Still from Andy Warhol's Blue Movie (1968). Image via whitney.org

Still from Andy Warhol's Blue Movie (1968). Image via whitney.org

Sometimes movies that bomb at first, actually become cult classics years later, and eventually garner art status. In his 2013 article entitled "Should Gloriously Terrible Movies Like The Room Be Considered 'Outsider Art'?" The Atlantic’s Adam Rosen argues that the 2003 American drama The Room, which is written, directed, produced by and stars Tommy Wiseau—and is often hailed the worst movie ever made—is in fact outsider art. Rosen writes, "The label [of outsider art] has traditionally applied to painters and sculptors... but it's hard to see why it couldn't also refer to Wiseau or any other thwarted, un-self-aware filmmaker." Since the definition of art is messy, and something not everyone agrees on, perhaps the greatest rule to remember is to keep an open mind and never entirely dismiss a movie as inartistic.

RELATED ARTICLES: