How to Teach Your Children to Care about Art

Upon entering Frieze New York

last May, I ran into a colleague with his two small children. As we

crossed the threshold of the bustling fair tent, the kids sprang into

action, making a beeline for a red Carsten Höller

octopus. They promptly plopped down beside it and began a

discussion—“What is it made of?” and “Why is it red?” were among

preliminary questions. A month or so later I’d see them again, this time

in Chelsea, marvelling over Jordan Wolfson’s animatronic puppet at David Zwirner.

Even to a stranger, it would have been clear that for these children,

going to see art was an integral part of their lives. Their intense

engagement with art (a level of enthusiasm that many adults struggle to

maintain) begged some questions. What is it about art that commands a

child’s attention? What impact can art have on a child’s development?

And more broadly, what can be done to instill an appreciation of art in

children?

To find answers, I turned to experts in the field who work at the intersections of children’s education and art. While primarily focusing on programs provided by museum spaces, I also consulted with other arts professionals and educators to establish a more complete picture of the underlying factors that can contribute to a child’s early appreciation of art—and how it affects a young person’s brain.

Over the past decade, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has found strong evidence showing that art can have a positive effect on young children (infants through eight-year-olds). A December 2015 NEA literature review conducted by program analyst Melissa Menzer, for example, found connections between the arts—including music, theater, visual arts, and literature—and social and emotional skills such as “helping, caring, and sharing activities.”

NEA arts education specialist Terry Liu, meanwhile, has found that more and more arts education grants are being funneled into the integration of arts with other disciplines in early childhood. “Teaching artists or organizations that have artists skilled in working with early childhood age groups are working with parents or Head Start centers to help them incorporate arts education and learning at this very early age,” Liu notes. In other words, art is no longer being siloed as a creative pursuit, but rather used “as a means to help children learn other subjects.”

Even further, Liu points to an increase in initiatives that are not just “reflecting on art and learning about art,” but also employing art to “make sense of how it relates to your understanding of the world.” Young people are being taught that art connects to the world around you.

To find answers, I turned to experts in the field who work at the intersections of children’s education and art. While primarily focusing on programs provided by museum spaces, I also consulted with other arts professionals and educators to establish a more complete picture of the underlying factors that can contribute to a child’s early appreciation of art—and how it affects a young person’s brain.

The benefits of art in early childhood

Over the past decade, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has found strong evidence showing that art can have a positive effect on young children (infants through eight-year-olds). A December 2015 NEA literature review conducted by program analyst Melissa Menzer, for example, found connections between the arts—including music, theater, visual arts, and literature—and social and emotional skills such as “helping, caring, and sharing activities.”

NEA arts education specialist Terry Liu, meanwhile, has found that more and more arts education grants are being funneled into the integration of arts with other disciplines in early childhood. “Teaching artists or organizations that have artists skilled in working with early childhood age groups are working with parents or Head Start centers to help them incorporate arts education and learning at this very early age,” Liu notes. In other words, art is no longer being siloed as a creative pursuit, but rather used “as a means to help children learn other subjects.”

Even further, Liu points to an increase in initiatives that are not just “reflecting on art and learning about art,” but also employing art to “make sense of how it relates to your understanding of the world.” Young people are being taught that art connects to the world around you.

Multiple

other studies have found a correlation between artmaking and emotional

regulation, which is a central tenet of art therapy. Psychologist

Jennifer Drake, an assistant professor at Brooklyn College, for example,

has conducted studies around the relationship between drawing and

emotional regulation among children and adults. Working with children in

the six- to twelve-year-old range, these studies have proven that

drawing can assuage the negative emotions a person feels upon being told

to recall the details surrounding a sad personal event. These results

are bolstering institutional programs and encouraging parents to engage

children in the arts from an early age—but how?

To start, it’s a cornerstone of art education programs to cultivate a symbiotic relationship between looking at art and creating it. In museums, it’s become standard practice for educators to develop art-making programs that engage audiences with the works in a current exhibition or permanent collection.

New York’s Whitney Museum, for example, has developed a vast array of programs to engage children of all ages (beginning with Stroller Tours for newborns and new parents), but one of its most popular programs is Open Studio, an in-house art studio led by graduate students that allows families to visit freely and create art on the weekends. “It’s a drop-in art-making program” says Billie Rae Vinson, coordinator of Family Programs, over the phone. “It’s a way to explore the artwork through some kind of material exploration.”

A day in the Open Studio program might involve crafting collages inspired by the high contrast found in an Edward Steichen photograph. “In museums it’s great to have discussions, but what do artists do?” asks Vinson. “They make stuff. We’ve got to get families making stuff.” The goals of this are double-pronged: to connect families with the activities of artists and to inspire creativity. “We’re not trying to be derivative or make parents or children copy or make little versions of the artworks on view; we want them to be inspired by these artists and then run with it for themselves.”

Similar models have been adopted by museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago, which has a daily artist’s studio program. “Art-making in the museum can be very powerful because it allows children to connect their own imaginative ways of making with art they see around them in the galleries,” says Jacqueline Terrassa, Chair of Museum Education there.

Despite this, the Art Institute recently saw a need to direct more attention back to the museum’s exhibitions. “We wanted to find a fun, interactive solution to the challenge of how to make the museum feel accessible and navigable for families,” Terrassa says. “Often families will come to the Art Institute and stay in the Ryan Learning Center instead of also exploring the galleries.” This past spring the museum launched a new digital initiative, JourneyMaker, which allows families to create custom tours through the museum focused around eight storylines, including superheroes, time travel, and strange and wondrous beasts.

In making their children’s programs family-focused, both the Whitney and the Art Institute have recognized not only that children often need a parent or guardian for supervision, but also the powerful shared experiences that children and adults can have while learning about and making art together. And as such, these programs become communal spaces for families. “I talked to one dad who told me that for him it was a bit like New York’s living room,” Vinson says of the Whitney’s space. “He told me his son learned to walk in our Open Studio while his daughter was making art.”

The idea of a communal space for art exploration is popular across numerous museums. The Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling, located on the ground floor of the David Adjaye-designed Sugar Hill Project in Harlem, which opened last October, has a large central gallery space called The Living Room. Currently painted with a vibrant narrative mural by artist Saya Woolfalk (in collaboration with her four-year-old daughter), it is dotted with bright orange benches and tables, where families gather to see and make art, and participate in music and storytelling performances.

Integrate looking and making

To start, it’s a cornerstone of art education programs to cultivate a symbiotic relationship between looking at art and creating it. In museums, it’s become standard practice for educators to develop art-making programs that engage audiences with the works in a current exhibition or permanent collection.

New York’s Whitney Museum, for example, has developed a vast array of programs to engage children of all ages (beginning with Stroller Tours for newborns and new parents), but one of its most popular programs is Open Studio, an in-house art studio led by graduate students that allows families to visit freely and create art on the weekends. “It’s a drop-in art-making program” says Billie Rae Vinson, coordinator of Family Programs, over the phone. “It’s a way to explore the artwork through some kind of material exploration.”

A day in the Open Studio program might involve crafting collages inspired by the high contrast found in an Edward Steichen photograph. “In museums it’s great to have discussions, but what do artists do?” asks Vinson. “They make stuff. We’ve got to get families making stuff.” The goals of this are double-pronged: to connect families with the activities of artists and to inspire creativity. “We’re not trying to be derivative or make parents or children copy or make little versions of the artworks on view; we want them to be inspired by these artists and then run with it for themselves.”

Similar models have been adopted by museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago, which has a daily artist’s studio program. “Art-making in the museum can be very powerful because it allows children to connect their own imaginative ways of making with art they see around them in the galleries,” says Jacqueline Terrassa, Chair of Museum Education there.

Despite this, the Art Institute recently saw a need to direct more attention back to the museum’s exhibitions. “We wanted to find a fun, interactive solution to the challenge of how to make the museum feel accessible and navigable for families,” Terrassa says. “Often families will come to the Art Institute and stay in the Ryan Learning Center instead of also exploring the galleries.” This past spring the museum launched a new digital initiative, JourneyMaker, which allows families to create custom tours through the museum focused around eight storylines, including superheroes, time travel, and strange and wondrous beasts.

In making their children’s programs family-focused, both the Whitney and the Art Institute have recognized not only that children often need a parent or guardian for supervision, but also the powerful shared experiences that children and adults can have while learning about and making art together. And as such, these programs become communal spaces for families. “I talked to one dad who told me that for him it was a bit like New York’s living room,” Vinson says of the Whitney’s space. “He told me his son learned to walk in our Open Studio while his daughter was making art.”

Create flexible, communal spaces for experiencing art

The idea of a communal space for art exploration is popular across numerous museums. The Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling, located on the ground floor of the David Adjaye-designed Sugar Hill Project in Harlem, which opened last October, has a large central gallery space called The Living Room. Currently painted with a vibrant narrative mural by artist Saya Woolfalk (in collaboration with her four-year-old daughter), it is dotted with bright orange benches and tables, where families gather to see and make art, and participate in music and storytelling performances.

In

adjacent spaces are a dedicated art studio, and gallery spaces—one for

rotating exhibitions developed by contemporary artists, sometimes in

collaboration with children, and one for shows done in partnership with

fellow museums El Museo del Barrio and The Studio Museum in Harlem.

“One of the reasons this museum was formed was as a lab to see what

happens when art education and curatorial exhibitions coexist,”

Associate Director of Curatorial Programs Lauren Kelley tells me, “to

see if there can be a more democratic approach to programming, as

opposed to the exhibitions being the reason for education to have

tasks.”

She emphasizes that artmaking and art education are not separated from engaging with the exhibitions—all of which involve the work of children, to varying degrees. The current show by Shani Peters was inspired by the artist’s work with children. Exhibitions such as this one have been successful in dissembling “the sense of sacredness associated with what it means to be a viewer, which can lead to people feeling really uncomfortable,” says Kelley. “We hope that we can disarm that from children at an early age, and then they leave here wanting to go to the Met, feeling like ‘this makes sense to me.’”

The Children’s Museum of the Arts (CMA) also integrates exhibition and art-making spaces. The museum’s tagline, “Look, Make, Share,” encompasses their approach to combining careful looking, art making, and dialogues around art. Artmaking activities here often relate to a central themed group exhibition (the current show focuses on sports; the next will be outer space) in its main gallery, which is flanked by multiple specialized studios. There is also a Clay Bar, where families can sign up to create playful sculptures.

“Making art familiar, an everyday event, rather than something isolated, also helps children become comfortable with it,” Terrassa offers. “Art is not only inside the museum—it’s all around you.” Jessica Hamlin, a professor of Arts Education at NYU Steinhardt, agrees. “There’s this constant back-and-forth between looking at works of art—how they can be looked at and understood, and building language and appreciation around them—and also the making,” she says. “But there’s a third piece: general aesthetic appreciation. We can bring that eye and that thinking to things we see in life.”

CMA executive director Barbara Hunt McLanahan believes it’s all about encouraging what comes naturally to children: curiosity. “I think that in a way you don’t instill an appreciation of art in children, children already have it.”

In her experience during Sugar Hill’s first year, Kelley has found this to be true as well. “They really are excited about people having faith in them,” she explains. “I think children really just appreciate you giving them the space and the square footage to play with materials. We don’t always give them prompts, sometimes we just see what happens; we say to them, ‘what do you think you can do with these stickers? This tape? You choose, you figure it out.’ We respect them as capable.”

She emphasizes that artmaking and art education are not separated from engaging with the exhibitions—all of which involve the work of children, to varying degrees. The current show by Shani Peters was inspired by the artist’s work with children. Exhibitions such as this one have been successful in dissembling “the sense of sacredness associated with what it means to be a viewer, which can lead to people feeling really uncomfortable,” says Kelley. “We hope that we can disarm that from children at an early age, and then they leave here wanting to go to the Met, feeling like ‘this makes sense to me.’”

The Children’s Museum of the Arts (CMA) also integrates exhibition and art-making spaces. The museum’s tagline, “Look, Make, Share,” encompasses their approach to combining careful looking, art making, and dialogues around art. Artmaking activities here often relate to a central themed group exhibition (the current show focuses on sports; the next will be outer space) in its main gallery, which is flanked by multiple specialized studios. There is also a Clay Bar, where families can sign up to create playful sculptures.

“Making art familiar, an everyday event, rather than something isolated, also helps children become comfortable with it,” Terrassa offers. “Art is not only inside the museum—it’s all around you.” Jessica Hamlin, a professor of Arts Education at NYU Steinhardt, agrees. “There’s this constant back-and-forth between looking at works of art—how they can be looked at and understood, and building language and appreciation around them—and also the making,” she says. “But there’s a third piece: general aesthetic appreciation. We can bring that eye and that thinking to things we see in life.”

Building children’s confidence in what they see

CMA executive director Barbara Hunt McLanahan believes it’s all about encouraging what comes naturally to children: curiosity. “I think that in a way you don’t instill an appreciation of art in children, children already have it.”

In her experience during Sugar Hill’s first year, Kelley has found this to be true as well. “They really are excited about people having faith in them,” she explains. “I think children really just appreciate you giving them the space and the square footage to play with materials. We don’t always give them prompts, sometimes we just see what happens; we say to them, ‘what do you think you can do with these stickers? This tape? You choose, you figure it out.’ We respect them as capable.”

Adults

are prone to decidedly affirm whether they’re artistic or not; that

they understand art or they don’t. “So many adults come to the museum

and say ‘I never did this because I wasn’t any good at art,’” McLanahan

offers, “and our answer to that is ‘You probably were, but you were

being told that maybe you weren’t good at drawing, perhaps you weren’t

introduced to printmaking or abstract art. You were being asked to draw

in a representational way and you didn’t enjoy that.” She adds that

attitudes about what does and does not qualify as art are mostly limited

to adults. “Children are way more open-minded.”

There are times when adults introduce judgements into the artmaking environment, and teachers at CMA have to step in. “I worry that we often teach creativity out of students rather than integrating it into the way we want all students to think of themselves, whether they become artists or not,” Hamlin says. “[Making art] correlates with development and brain science. It’s nurture and nature, not versus.” Hamlin notes that elementary school art classes that focus on skills and provide guidelines for what drawing should look like can be detrimental. “I think an emphasis on driving home skills-based instruction can be difficult for early childhood—it reinforces that there are good skills and bad skills, that there are people who have skills and people who don’t.”

In her studies on correlations between drawing and mood regulation, Drake found that in the 10- to 12-year-old age range, children become critical of their drawings skills. “They start to understand that they have limitations and that they can be good in some things and not at other things,” Drake says. “Six- to eight-year-olds are really absorbed in drawing, they can get more lost in it.”

In order to encourage creativity, many museums have adopted an inquiry-based approach, whereby educators prompt children through open-ended questions—emphasizing that there’s no right answer—in order to elicit ideas and incite discussion around art. “It’s really about asking them, ‘What do you see? How does it make you feel? What do you think the artist meant here? Why did they use this material?’ and encouraging them to have confidence in their answers,” says McLanahan. “We encourage you to have confidence in your ability to look and understand, but then we want you to respect someone else’s creativity and someone else’s opinion when we share.”

Understanding the simple fact that children want to be spoken to like adults, and that cossetting them at a young age can be a hindrance to their development, is central for many art educators. “There’s nothing about our exhibiting artists that makes them suited to children,” McLanahan says of CMA’s program. “It’s just that we’re actively encouraging children to use their minds and think about the work and talk about the work.” Underlying this approach is a recognition of the innate sophistication of children.

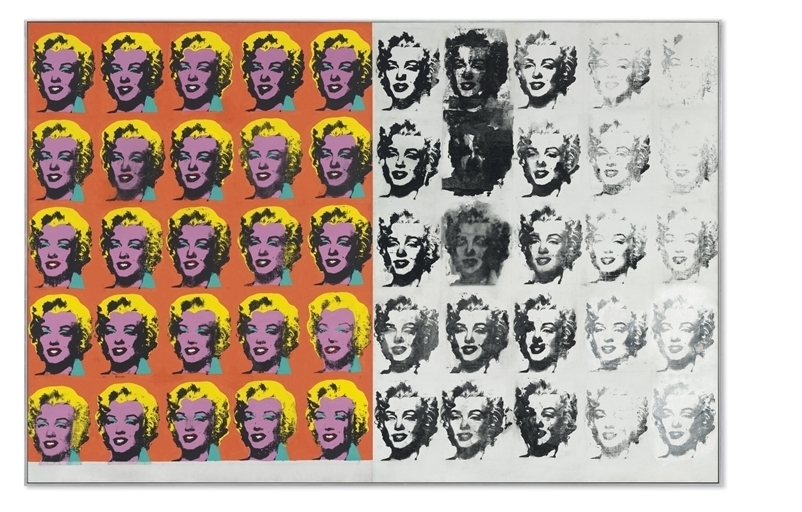

CMA puts on shows of emerging and established contemporary artists (the current show includes Hank Willis Thomas, Dario Escobar, and Zoe Buckman, among others); at Sugar Hill, Kelley is engaging contemporary artists living in Upper Manhattan. “If you dumb it down, if you think that children only like graffiti or cartoons or Keith Haring—it’s a dead end,” McLanahan advises. “We have wall labels that explain what the artist’s intentions are, we try not to use jargon, and we don’t over-explain the work.”

At the Art Institute, an encyclopedic museum that not only caters to all ages but a vast array of international audiences, a similar mindset prevails. “No art, no matter how abstract or supposedly ‘difficult,’ is off-limits for children,” Terrassa notes. “That said, some artwork, because of style or content, might resonate more at different stages of life. For example, artwork that engages with questions of identity might be great for teens, and highly experiential, abstract works can be a hit with very little ones.” She acknowledges that there will be art that may not reflect a family’s values, in which case it is up to a parent or guardian’s discretion.

While visual culture is often boiled down to its essential elements of shape and color, especially for younger audiences, it’s important to keep ideas and narratives top of mind. “Sometimes we underestimate what young kids are able to talk about and do, and read into things,” Hamlin notes. “It’s important to present a balance of pure, aesthetic elements and principles with an understanding of art as a form of communication that helps us talk, express, and connect with each other and with diverse experiences.”

More and more, museums, schools, and community organizations are recruiting contemporary artists to teach children. The Whitney regularly holds artist-led workshops; all teachers at CMA are practicing artists; and Sugar Hill has an artist in residence each year who interacts with children at the museum, as well as its affiliate preschool. “As social practice art gains traction in the art world and that becomes a way of thinking about what artists can do, museums are really being receptive to artists wanting to do more than just put their objects in a museum,” Hamlin says of this trend. “Artists should be real human beings for kids, not just mythical characters.”

There are times when adults introduce judgements into the artmaking environment, and teachers at CMA have to step in. “I worry that we often teach creativity out of students rather than integrating it into the way we want all students to think of themselves, whether they become artists or not,” Hamlin says. “[Making art] correlates with development and brain science. It’s nurture and nature, not versus.” Hamlin notes that elementary school art classes that focus on skills and provide guidelines for what drawing should look like can be detrimental. “I think an emphasis on driving home skills-based instruction can be difficult for early childhood—it reinforces that there are good skills and bad skills, that there are people who have skills and people who don’t.”

In her studies on correlations between drawing and mood regulation, Drake found that in the 10- to 12-year-old age range, children become critical of their drawings skills. “They start to understand that they have limitations and that they can be good in some things and not at other things,” Drake says. “Six- to eight-year-olds are really absorbed in drawing, they can get more lost in it.”

In order to encourage creativity, many museums have adopted an inquiry-based approach, whereby educators prompt children through open-ended questions—emphasizing that there’s no right answer—in order to elicit ideas and incite discussion around art. “It’s really about asking them, ‘What do you see? How does it make you feel? What do you think the artist meant here? Why did they use this material?’ and encouraging them to have confidence in their answers,” says McLanahan. “We encourage you to have confidence in your ability to look and understand, but then we want you to respect someone else’s creativity and someone else’s opinion when we share.”

Don’t dumb it down

Understanding the simple fact that children want to be spoken to like adults, and that cossetting them at a young age can be a hindrance to their development, is central for many art educators. “There’s nothing about our exhibiting artists that makes them suited to children,” McLanahan says of CMA’s program. “It’s just that we’re actively encouraging children to use their minds and think about the work and talk about the work.” Underlying this approach is a recognition of the innate sophistication of children.

CMA puts on shows of emerging and established contemporary artists (the current show includes Hank Willis Thomas, Dario Escobar, and Zoe Buckman, among others); at Sugar Hill, Kelley is engaging contemporary artists living in Upper Manhattan. “If you dumb it down, if you think that children only like graffiti or cartoons or Keith Haring—it’s a dead end,” McLanahan advises. “We have wall labels that explain what the artist’s intentions are, we try not to use jargon, and we don’t over-explain the work.”

At the Art Institute, an encyclopedic museum that not only caters to all ages but a vast array of international audiences, a similar mindset prevails. “No art, no matter how abstract or supposedly ‘difficult,’ is off-limits for children,” Terrassa notes. “That said, some artwork, because of style or content, might resonate more at different stages of life. For example, artwork that engages with questions of identity might be great for teens, and highly experiential, abstract works can be a hit with very little ones.” She acknowledges that there will be art that may not reflect a family’s values, in which case it is up to a parent or guardian’s discretion.

While visual culture is often boiled down to its essential elements of shape and color, especially for younger audiences, it’s important to keep ideas and narratives top of mind. “Sometimes we underestimate what young kids are able to talk about and do, and read into things,” Hamlin notes. “It’s important to present a balance of pure, aesthetic elements and principles with an understanding of art as a form of communication that helps us talk, express, and connect with each other and with diverse experiences.”

Expose children to the contemporary art world

More and more, museums, schools, and community organizations are recruiting contemporary artists to teach children. The Whitney regularly holds artist-led workshops; all teachers at CMA are practicing artists; and Sugar Hill has an artist in residence each year who interacts with children at the museum, as well as its affiliate preschool. “As social practice art gains traction in the art world and that becomes a way of thinking about what artists can do, museums are really being receptive to artists wanting to do more than just put their objects in a museum,” Hamlin says of this trend. “Artists should be real human beings for kids, not just mythical characters.”

And

many artists are eager to engage with children. “It’s important to me

to give the children in the communities I work with a voice for their

stories and a way to share those stories,” says David Shrobe, the first artist in residence at Sugar Hill, “and this is a space I was able to activate, a space for community.”

While museums have done well to recruit contemporary artists to teach in their institutions, children are rarely exposed to other roles they may pursue in the art world. One program addressing this absence is Frieze Teens, part of the non-profit arm of Frieze New York, a small but strong annual program that grants access to the contemporary art world to a group of 25 New York City public school students each year.

Participating teens from underserved communities are exposed to many facets of the art world, in hope of inspiring them to pursue a career in the field. “By seeing a work from its inception in a studio with the artists and then tracking through critics, curators, gallerists, fabricators, non-profits etc.—really anyone and everyone involved in that process—it gives these kids access to the full range of ways one could engage and participate in the art world,” Molly McIver, Head of Operations at Frieze New York told me.

But even more than presenting young people with career options, contemporary art offers an entrypoint into a more expansive, diverse understanding of art. Hamlin points out that the art historical canon that we lean so heavily on is no longer representative of the majority of students who are learning from it—in terms of gender, ethnicity and social, political, and sexual identities. “I think that we’re seeing the limitations of that canon, and yes there’s amazing work and beautiful work, but artists have been making work all over the world for thousands of years, and that’s a really important part of the conversation.”

But it won’t come easy. “There’s a whole set of things that teachers have to work against to bring the contemporary into their coursework,” says Hamlin. In addition to combating entrenched biases toward producing aesthetically pleasing objects, it’s hard for teachers to keep up with a continually shifting art world. “It’s a large hill to climb—there are changing ideas and notions around what art is, what art education can be, what artistic practices are, there’s this constantly evolving landscape of art practice.” So while there is a growing recognition of the importance of children engaging with art, manifold challenges remain.

“I think a lot of museums are really reassessing what it means to cater to this wee demographic,” Kelley tells me at Sugar Hill. “The obvious fact is that you’re building an audience from the ground up, and you’re tapping into a demographic that usually feels excluded—limited by a museum experience of ‘please don’t touch.’ We do not have any answers yet, but being allowed to be in this kind of lab, we can be ambitious with what we’re going to test out.” That’s all we can ask.

—Casey Lesser

While museums have done well to recruit contemporary artists to teach in their institutions, children are rarely exposed to other roles they may pursue in the art world. One program addressing this absence is Frieze Teens, part of the non-profit arm of Frieze New York, a small but strong annual program that grants access to the contemporary art world to a group of 25 New York City public school students each year.

Participating teens from underserved communities are exposed to many facets of the art world, in hope of inspiring them to pursue a career in the field. “By seeing a work from its inception in a studio with the artists and then tracking through critics, curators, gallerists, fabricators, non-profits etc.—really anyone and everyone involved in that process—it gives these kids access to the full range of ways one could engage and participate in the art world,” Molly McIver, Head of Operations at Frieze New York told me.

But even more than presenting young people with career options, contemporary art offers an entrypoint into a more expansive, diverse understanding of art. Hamlin points out that the art historical canon that we lean so heavily on is no longer representative of the majority of students who are learning from it—in terms of gender, ethnicity and social, political, and sexual identities. “I think that we’re seeing the limitations of that canon, and yes there’s amazing work and beautiful work, but artists have been making work all over the world for thousands of years, and that’s a really important part of the conversation.”

But it won’t come easy. “There’s a whole set of things that teachers have to work against to bring the contemporary into their coursework,” says Hamlin. In addition to combating entrenched biases toward producing aesthetically pleasing objects, it’s hard for teachers to keep up with a continually shifting art world. “It’s a large hill to climb—there are changing ideas and notions around what art is, what art education can be, what artistic practices are, there’s this constantly evolving landscape of art practice.” So while there is a growing recognition of the importance of children engaging with art, manifold challenges remain.

“I think a lot of museums are really reassessing what it means to cater to this wee demographic,” Kelley tells me at Sugar Hill. “The obvious fact is that you’re building an audience from the ground up, and you’re tapping into a demographic that usually feels excluded—limited by a museum experience of ‘please don’t touch.’ We do not have any answers yet, but being allowed to be in this kind of lab, we can be ambitious with what we’re going to test out.” That’s all we can ask.

—Casey Lesser