There are good reasons to worry about the future of humanity. Do we have a future, and if so, how much and what kind? For most people, it’s easier to feel these existential concerns for our species than it is to do something about them. But some are taking action. On 27 September 2016, the SpaceX founder Elon Musk made a bold, direct claim: that, in order to survive an inevitable extinction event, humans would need to ‘become a space-faring civilisation and a multi-planetary species’. Pulses raced and the media swooned. Headlines appeared in the business and technology press about Musk’s plan to save humanity. Experts and laypeople alike debated details of the rockets, spacecraft and fuel needed for Musk’s journey to Mars. The excitement was palpable, and it was evident at the press conference. During the Q&A that followed the announcement, Musk said that his goal was to inspire humanity. One audience member yelled: ‘[Musk] inspires the shit out of us!’ Another offered him a kiss.

Musk’s plan to colonise Mars is a sign of an older and recurring social problem. What happens when the rich and powerful isolate themselves from everyday concerns? Musk wants to innovate and leave Earth, rather than to take care of it, or fix it, and stay. Like so many of his peers in the innovating and disrupting classes, Musk prefers to dwell in fantasy and science fiction, safely removed from the world of here and now.

Musk is a utopian, in the original Greek meaning: ‘no place’. Repulsed by the world we all share, he dreams of a place that does not exist.

His announcement parallels an earlier moment in the history of spaceflight, the Apollo missions of the 1960s to send American men to the Moon. Musk himself made the comparison, when he described the Apollo missions as ‘probably the greatest achievements of humanity’. The US space program got a major boost from Cold War competition with the Soviet Union, especially the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957. The extraordinary achievement of Sputnik pushed US scientists and political leaders to try to re-establish the country’s scientific and technological supremacy. The Apollo missions began a few years later, with President John F Kennedy’s bold declaration in 1961, and culminated with the manned Moon landing of Apollo 11 on 20 July 1969. The program captured the imagination of the nation, indeed the world, and remains an inspiring story of teamwork, wonder, technological achievement and ingenuity.

Get Aeon straight to your inbox

The lore of Apollo 11 as a Cold War triumph also serves to direct attention away from some of the less glorious aspects of the US at the time. Many contemporary Americans viewed the Apollo program with deep skepticism, and some were even morally critical. One such critic was the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, who became president of the Southern Christian Leadership Council after Martin Luther King’s assassination in April 1968.

Before his death, King had turned his political activism toward the problems of economic inequality and poverty. Abernathy stayed with this focus, and continued to organise people around addressing economic issues for black and white Americans. In July 1969, with the Apollo 11 launch, Abernathy saw an opportunity to keep economic justice on the nation’s conscience. He announced a march to Cape Canaveral in Florida, the rocket launch site. Accompanied by a few hundred people, Abernathy asked for a meeting with NASA. He wanted to win NASA’s support and technical expertise in the fight against poverty, hunger and social problems. Abernathy told NASA officials, as one of them recalled: ‘The money for the space program should be spent to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, tend the sick, and house the shelterless.’ To NASA’s credit, their historian and Smithsonian curator Roger Launius has

documented and published on Abernathy’s protests and his dialogue with NASA.

Abernathy’s insight about the priorities of a country that could send men into space while millions of Americans lacked medical care, shelter and food found a new voice in Gil Scott-Heron. The poet and musician, who had cultivated a reputation for his socially charged spoken-word performances, debuted a new piece: ‘Whitey on the Moon’ (1970):

A rat done bit my sister Nell

(With Whitey on the Moon)

Her face and arms began to swell

(And Whitey’s on the Moon)

I can’t pay no doctor bill

(But Whitey’s on the Moon)

Ten years from now I’ll be paying still

(While Whitey’s on the Moon)

But neither Abernathy’s protest nor Scott-Heron’s anthem moved the country’s political priorities from space exploration to the provision of housing or health care. US adventures into outer space – white men in expensive, gleaming white spaceships – captivated popular attention and support in ways that urban poverty did not. Americans continued to send their tax revenues to the heavens.

Musk grew up far removed from the systematic racism and violence that characterised apartheid in South Africa

The civil rights movement faltered in the late 1960s, while US pre-eminence in space exploration persisted until the advent of the 21st century. With the end of the Cold War, the driving political impetus for investments in the space race collapsed too. NASA budgets were slashed, and the 1986 Challenger explosion and the 2003 Columbia shuttle disaster contributed to the ending of the manned space program. In the meantime, both presidents George W Bush and Barack Obama sought to move the space program away from dependence on American taxpayers. Their solution was to increase US reliance on international collaboration (after the launch of the International Space Station in 1998), and on partnerships with private companies. Founded in 2002, Musk’s SpaceX has become one of the most powerful of the private space companies.

How did Musk become a leader of the most capital-intensive and symbolically loaded sector in the US high-tech economy?

Ashlee Vance’s biography Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future (2015) provides some useful details. A child of privilege, Musk grew up in one of the largest homes in Pretoria in South Africa, far removed from the systematic racism and violence that characterised the country’s apartheid regime. Musk showed early technical promise: when he was 12, he created a video game – Blastar – set in outer space.

However, not all was happy in the Musk household. His parents divorced when he was young, leaving Musk to be raised by his abusive father. The boy developed the habit of detaching from reality and entering a dreamlike space of imagination. Later, he would envision new technologies in this state. As a child, he was known as a spaced-out nerd who corrected his peers’ mistakes. He was bullied. By his teen years, Musk fantasised about escaping South Africa for the US. After he graduated from high school in 1989, he followed through on these dreams, leaving behind his impoverished and racially divided country.

Musk moved first to Canada and then the US, and earned degrees in physics and economics from the University of Pennsylvania before heading to California with entrepreneurial ambitions. With a $30,000 gift from their father, in 1995 Elon and his brother Kimbal created a company called Zip2, which combined city directories, advertisements and mapping. Four years later, Compaq bought Zip2 for more than $300 million. Musk’s next venture was in online banking and email payments. A year on, Musk’s company, X.com, merged with PayPal; two years on, eBay bought the joint venture for $1.5 billion in stock, with $165 million of it going to Elon.

From his early days in business, Musk developed a reputation for harshness. He chastised one employee who missed a company event to be at the birth of his child: ‘You need to figure out where your priorities are. We’re changing the world and changing history, and you either commit or you don’t.’ The Canadian author Justine Musk, his first wife, recounted to his biographer:

Elon is not someone who would say: ‘I feel you. I see your point of view.’ Because he doesn’t have that ‘I feel you’ dimension, there were things that seemed obvious to other people that weren’t that obvious to him.

Musk himself admits that, in his early years as a leader, he assumed that ‘other people will behave like you’. He grew frustrated when he realised that people didn’t behave like him. He lacked a natural ability to empathise with other people’s experiences and points of view.

With the payoffs from Zip2 and PayPal, Musk had arrived to the macho world of Silicon Valley riches. But he never rested on his laurels, nor was he willing to just live the life of a playboy. (Musk likes to say that he is ‘10 per cent playboy, 90 per cent engineer.’) He faced a choice: what to do next? He dreamed big. At his Caltech commencement address in 2012, he explained:

I thought, well, what are some of the other problems that are likely to most affect the future of humanity? Not from the perspective, ‘What’s the best way to make money’, which is okay, but, it was really ‘What do I think is going to most affect the future of humanity?’

Musk hit upon two endeavours: first, to create sustainable-energy technologies, which led to his involvement with Tesla Motors. Second, to go to Mars, which led to SpaceX. There is a profound moral distance between the types of problems that Tesla Motors and SpaceX seek to resolve.

Tesla Motors, founded in 2003, originally put out a plug-in electric luxury sports car: the Roadster. Tesla has always worked towards producing an affordable model that would make electric vehicles a realistic option for people. With a starting price of $35,000, the Tesla Model 3 is a big step in this direction. Tesla cars combine new technologies, such as improved lithium-ion batteries, with ideas about electric vehicles that have lain dormant for generations. The result is a sleek car with terrific performance. It also happens to move us toward clean energy.

Musk and his fellow Teslans have made electric vehicles cool, sexy and relatively affordable. That is commendable. There’s still a lot of work to be done, however, to move the vast majority of the Earth’s inhabitants toward clean energy. And there is little evidence that Tesla will move beyond high-end, niche products. The Tesla Powerwall, for example, is a battery system that supplies power to households off the electric grid. But with a lifetime cost that is higher than purchasing energy from a utility company, the Powerwall appeals mainly to wealthy homeowners who cannot stomach the idea of being without their gadgets during power outages.

It is in this context that Musk’s fantasy of bringing human civilisation to Mars is best understood. A trip to Mars requires awe-inspiring technological advance and immense wealth. It catalyses something deep inside the human imagination. It is also at least as removed from the needs and experiences of humans, and Musk’s own society… as Earth is from Mars.

Musk insists that humans in fact ‘need’ to go to Mars. The Mars mission, he argues, is the best way for humanity to become what he calls a ‘space-faring civilisation and a multi-planetary species’. This otherworldly venture, he says, is necessary to mitigate the ‘existential threat’ from artificial intelligence (AI) that might wipe out human life on Earth. Musk’s existential concerns, and his look to other worlds for solutions, are not unique among the elite of the technology world. Others have expressed what might best be understood as a quasi-philosophical paranoia that our Universe is really just a simulation inside a giant computer.

Musk himself has fallen under the sway of the Oxford philosopher

Nick Bostrom, who put forward the simulation

theory in 2003. Bostrom has also

argued that addressing ‘existential risks’ such as AI should be a global priority. The idea that Google’s CEO Larry Page might create artificially intelligent robots that will destroy humanity reportedly keeps Musk up at night. ‘I’m really worried about this,’ Musk told his biographer. ‘He could produce something evil by accident.’

These subjects could provide some teachable moments in certain kinds of philosophy classes. They are, obviously, compelling plot devices for Hollywood movies. They do not, however, bear any relationship to the kinds of existential risks that humans face now, or have ever faced, at least so far in history. But Musk has no connection to ordinary people and ordinary lives. For his 30th birthday, Musk rented an English castle, where he and 20 guests played hide-and-seek until 6am the following day. Compare this situation with the stories recounted in Matthew Desmond’s book Evicted (2016), where an entire housing industry has arisen in the US to profit from the poverty of some families, who often move from home to home with little hope of ever catching up, let alone getting ahead.

What led Musk to develop such contempt for the billions of humans who could never escape Earth?

Musk estimates the cost of the Mars mission at around $10 billion per person. His goal is to reduce that cost to $200,000 per person. He said this would allow ‘almost anyone’ to save up and buy a trip to Mars. At the risk of labouring the obvious, aren’t there better ways to spend the money? Who undertakes a multibillion-dollar otherworldly project in the name of abstract ‘humanity’, when so many humans around us need help achieving the most basic existence? To protect humanity from existential threats, one can imagine a multibillion-dollar asteroid-defence system that would keep humans from sharing the same fate as the dinosaurs. One could also invest multiple billions into existing philanthropies, such as those that protect the health, safety and education of vulnerable human beings.

Or, take other risks to planet Earth and its human occupants: the calamity of climate change and rising oceans; infectious diseases; or the slow disaster of infrastructural decay. For $10 billion dollars, the US could fully deploy positive train-control systems that would avoid such tragic accidents as recently seen in Philadelphia and Hoboken in New Jersey. For $1.5 billion, we could upgrade the lead-contaminated water infrastructure in Flint, Michigan; for $400 billion, we could repair the water infrastructure of the entire US. It’s jarring to think that one of the brightest minds of our age would rather fund 40 trips to Mars than keep children in his own country safe from poisoned water. It’s enough to make one wonder what led Musk to develop such contempt for the billions of humans who could never escape Earth.

Lucianne Walkowicz, an astronomer at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago and a critic of the ‘hubris’ of using Mars as a ‘backup planet’, puts this point simply and directly: ‘The idea that Mars will somehow save us from the decisions we’ve made is a false one.’ If we ‘truly believe in our ability to bend the hostile environments of Mars for human habitation, then we should be able to surmount the far easier task of preserving the habitability of the Earth.’

Musk’s plan is, of course, not to save the Earth. Rather, he needs an excuse to justify his outrageous plan to colonise Mars, and so he appeals to the preservation of, in his word, ‘humanity’. But Musk’s concept of humanity excludes most living and breathing humans. In his September 2016 announcement, he declared that a fully self-sustaining civilisation on Mars would need around 1 million people. From Earth’s current population of 7.125 billion, the Musk Million would bring 0.014035087719298244 per cent of it to Mars.

We are surprised that Musk’s plan has drawn only limited critical engagement. Most of the critical response has been to his technical assumptions and plans. We understand the many reasons that compel people to set aside practical concerns – Earthly concerns, as the case may be – and to support plans to explore and colonise Mars. The thirst for adventure, to reach for the stars, and to pursue the sublime is worthy, perhaps commendable. Even a dedicated activist such as the Rev Abernathy, who protested NASA’s launch in 1969, was overcome by a sense of awe. When he watched Apollo 11 take flight, he ‘really forgot the fact that we had so many hungry people’.

Who are we to tell Musk – or any private citizen, for that matter – what he should or shouldn’t do with his money? In US society, to question societal norms of conspicuous consumption, no matter how juvenile or vain, is frowned upon. Musk’s million-dollar McLaren sports car could buy more than 345,000 meals for the hungry. But it is up to Musk to make his decisions about his resources, not us. Our criticism comes in part from Musk’s position as a leader and role model. And we are sure he has failed in this regard.

We are his fellow citizens, fellow humans, and we don’t want people to follow in the direction Musk is leading. He could lead others to help those suffering now, to get involved in addressing the actual problems before us. There’s no shortage of them. If Musk prefers the planetary scale of action, he could lead people to preserve our single planetary resource, also known as Earth, the only planet we will probably ever have. Even on Musk’s own optimistic terms, his adolescent space fantasies will benefit only 0.014 per cent of humanity. He makes the politicians who serve the 1 per cent seem like communists.

Was all that money I made last year

For Whitey on the Moon?

How come there ain’t no money here?

Hmm! Whitey’s on the Moon

Some might justify investments in a mission to Mars by arguing that the US space program in general, and NASA’s achievements with Apollo in particular, brought tangible economic and even greater symbolic benefits. The symbolic payoff is clear: nothing seems to pique a spirit of wonder, curiosity, ambition and humility quite like space exploration and discovery. The economic payoffs are evident, ostensibly, in ‘spinoff’ or ‘spillover’ innovations. Up to 80 per cent of the technologies created for NASA programs might have ended up in the domestic economy. Just visit NASA’s searchable

database to learn more about the spinoffs that NASA is eager to publicise to taxpayers.

At this point in history, the colonisation of Mars is a distraction from the severe problems facing human societies

But as a way of making decisions about research and development, and science and technology investment, the ‘spinoff’ publicity campaign reveals its own weakness. Quite simply, why not address the existential problems facing our society and our fellow humans directly? We don’t need trickle-down science. A public research agenda aimed squarely at solving real problems – for example, an attempt to reduce the cost and improve the quality of inexpensive housing – would easily produce useful technologies that exceed the 80 per cent mark. ‘Spillover’ is a poor, indeed bizarre and indefensible justification. Let’s simply unfurl the metaphor. People around you are thirsty, very thirsty, perhaps even dying of thirst. You have a lot of clean water. What to do? Should you fill a giant cistern until it overflows onto the ground, spilling over, and let the thirsty scramble to lick up the water? There’s a simpler, better way.

Mahatma Gandhi said: ‘Action expresses priorities.’ Our concerns are moral concerns about the priorities that Musk is articulating and that his followers are echoing. At this point in human history, the colonisation of Mars is a distraction from the severe problems facing human societies. The moral detachment of the plan signifies a deeper pathology that afflicts our culture of innovation, and celebrates innovators such as Musk, who are all too eager to play with gadgets and leave their fellow humans behind.

Sadly, Musk’s escapist vision is widely shared in the science-fiction-centred, tech-obsessed culture of Silicon Valley, where companies increasingly build apps just for the luxury service economy. The future was supposed to answer questions such as: Where is my jetpack? Where is my flying car? But it is still possible to pose different questions: Where is our economic bill of rights? Who will be the next Ralph Abernathy? Who will be our Gil Scott-Heron? Shouldn’t we be ashamed for having given up on protests against inequality? Shouldn’t we be ashamed for spending so much time and effort to raise money to put Whitey on Mars? How do we get our technology leaders to focus on real societal problems, including those faced by the least fortunate among us? Until we are able to answer these questions collectively, Elon’s moral failures are outpaced only by our own.

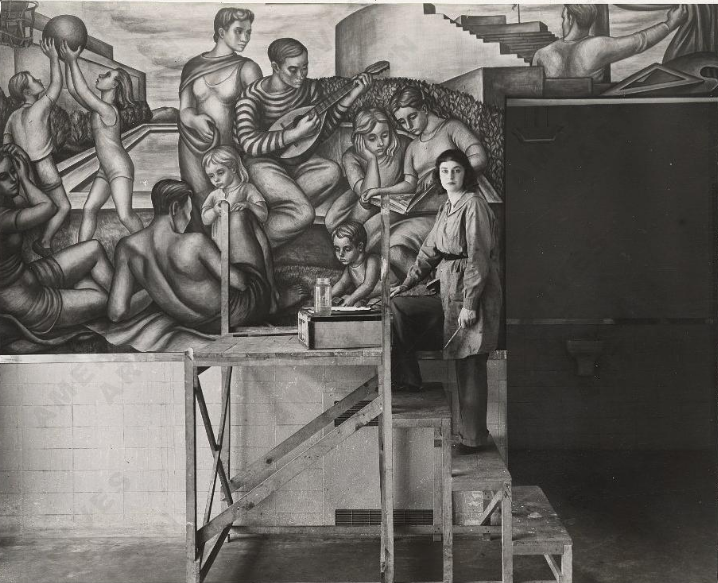

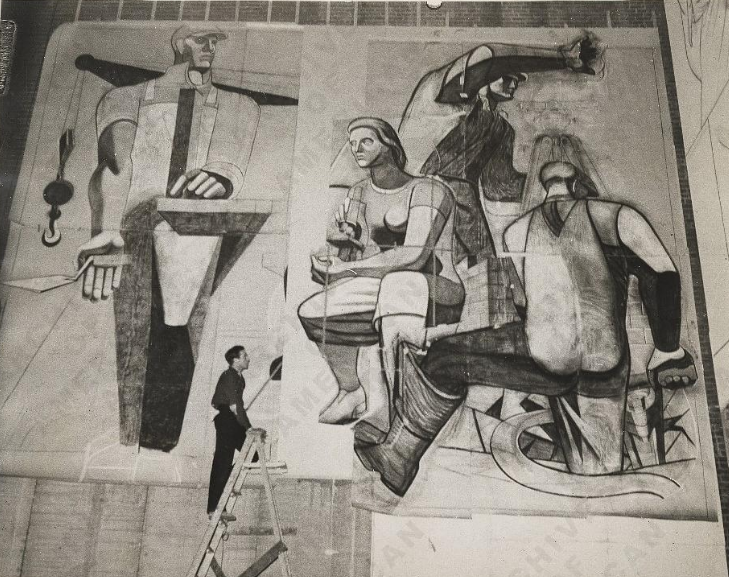

Marion Greenwood with a mural she created for the WPA. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

Marion Greenwood with a mural she created for the WPA. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art. Philip Guston working on a mural for the WPA. Photograph by Robbins. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

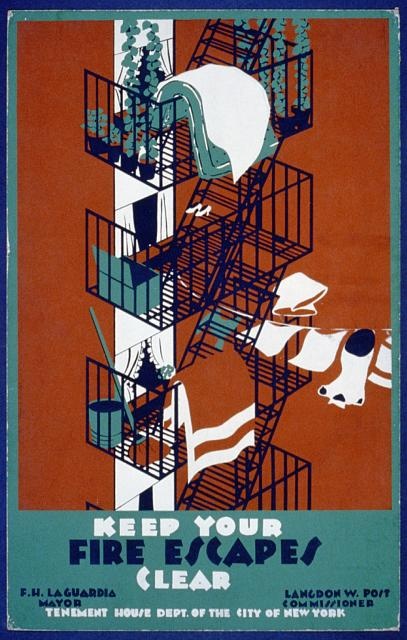

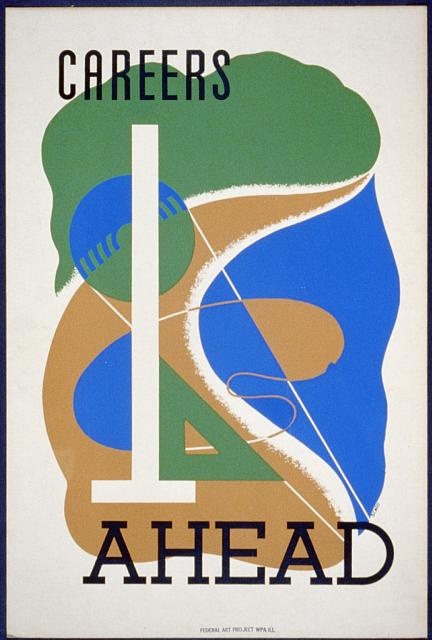

Philip Guston working on a mural for the WPA. Photograph by Robbins. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art. 1936 or 1937 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

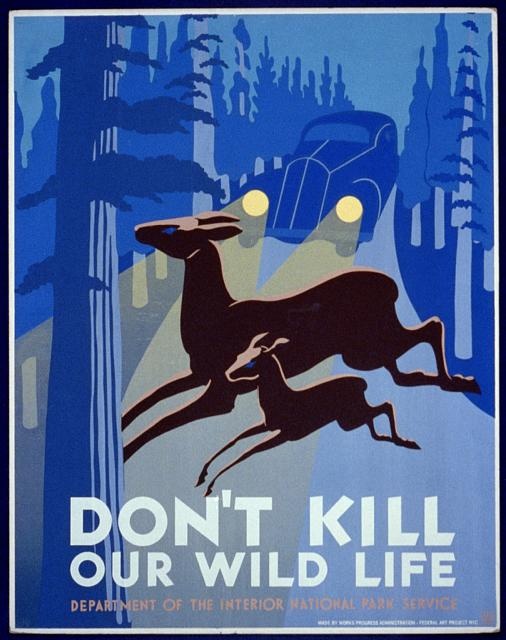

1936 or 1937 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. 1940 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

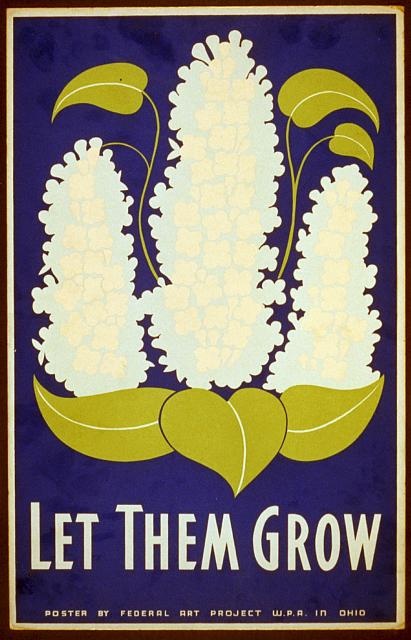

1940 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. Poster by Stanley Thomas, Clough, 1938. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

Poster by Stanley Thomas, Clough, 1938. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. 1939 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

1939 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. Poster by Maurice Merlin, 1943. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

Poster by Maurice Merlin, 1943. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. Poster created between 1936 and 1941. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

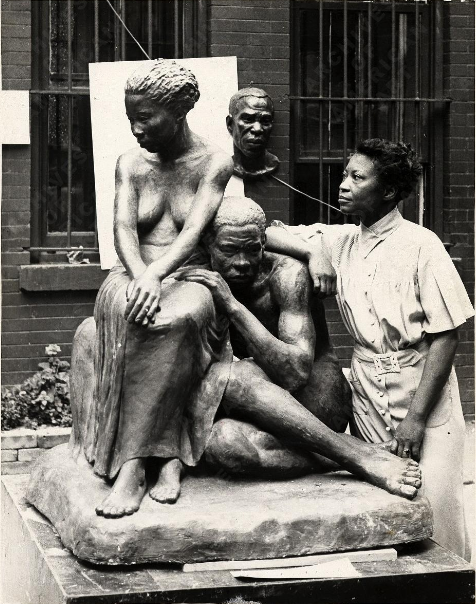

Poster created between 1936 and 1941. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. Augusta Savage with her sculpture Realization. Photograpy by Herman. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

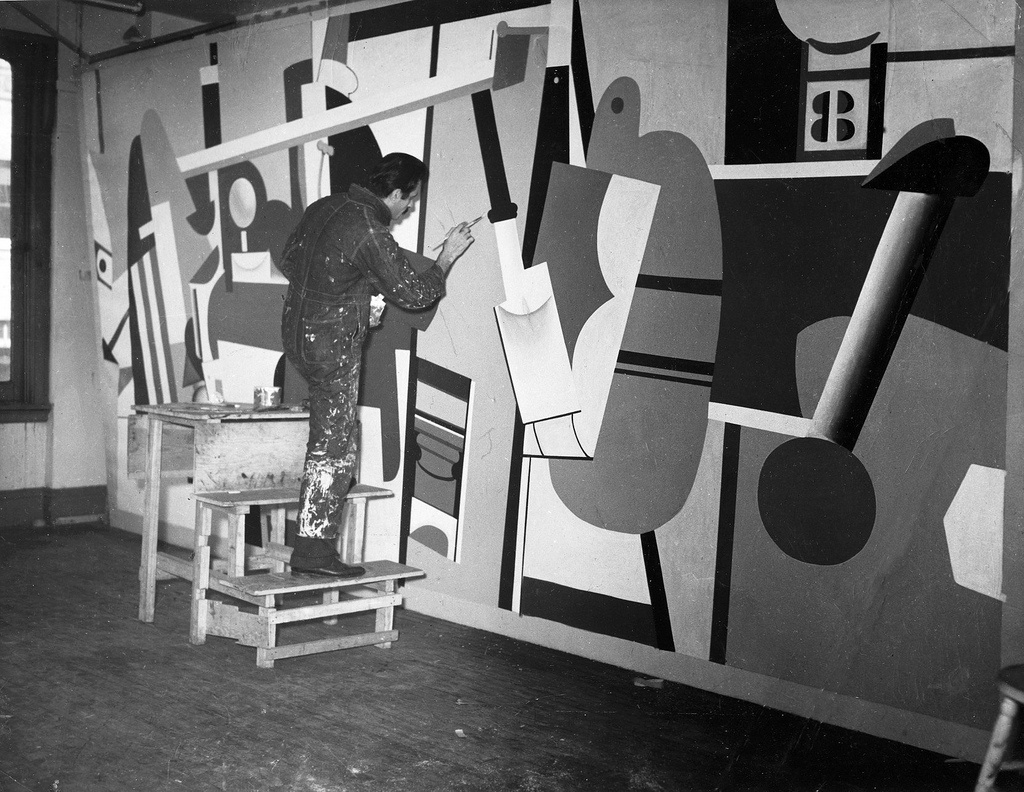

Augusta Savage with her sculpture Realization. Photograpy by Herman. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art. Arshile Gorky working on one of the panels for his “Aviation” murals for the Newark Airport. Photo via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

Arshile Gorky working on one of the panels for his “Aviation” murals for the Newark Airport. Photo via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.