A biotech company says it put dopamine-making cells into people’s brains

The experiment to treat Parkinson’s is a critical early test of stem cells’ potential to tackle serious disease.

In an important test for stem-cell medicine, a biotech company says implants of lab-made neurons introduced into the brains of 12 people with Parkinson’s disease appear to be safe and may have reduced symptoms for some of them.

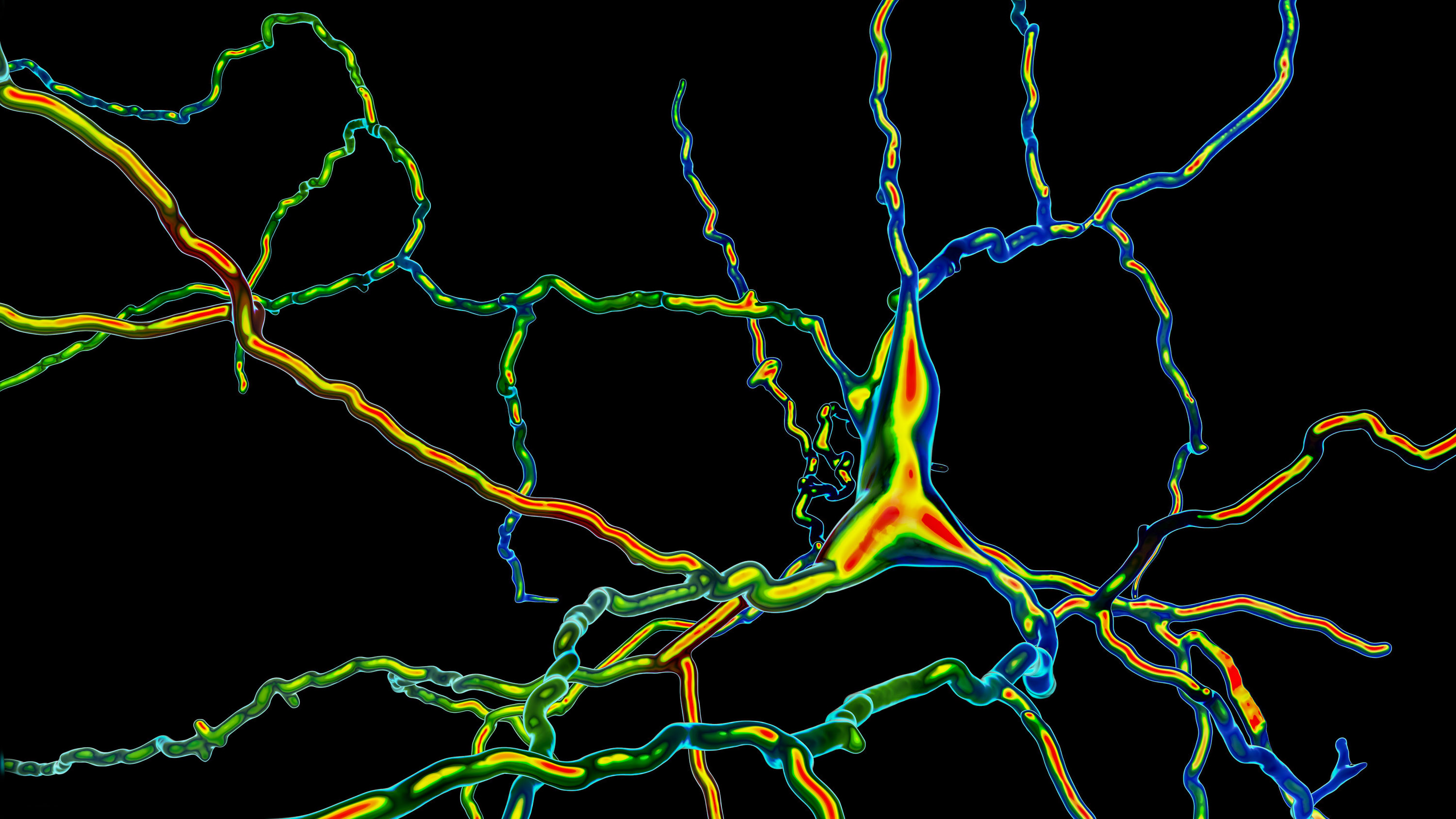

The added cells should produce the neurotransmitter dopamine, a shortage of which is what produces the devastating symptoms of Parkinson’s, including problems moving.

“The goal is that they form synapses and talk to other cells as if they were from the same person,” says Claire Henchcliffe, a neurologist at the University of California, Irvine, who is one of the leaders of the study. “What’s so interesting is that you can deliver these cells and they can start talking to the host.”

The study is one of the largest and most costly tests yet of embryonic-stem-cell technology, the controversial and much-hyped approach of using stem cells taken from IVF embryos to produce replacement tissue and body parts.

The small-scale trial, whose main aim was to demonstrate the safety of the approach, was sponsored by BlueRock Therapeutics, a subsidiary of the drug giant Bayer. The replacement neurons were manufactured using powerful stem cells originally sourced from a human embryo created an in vitro fertilization procedure.

According to data presented by Henchliffe and others on August 28 at the International Congress for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder in Copenhagen, there are also hints that the added cells had survived and were reducing patients’ symptoms a year after the treatment.

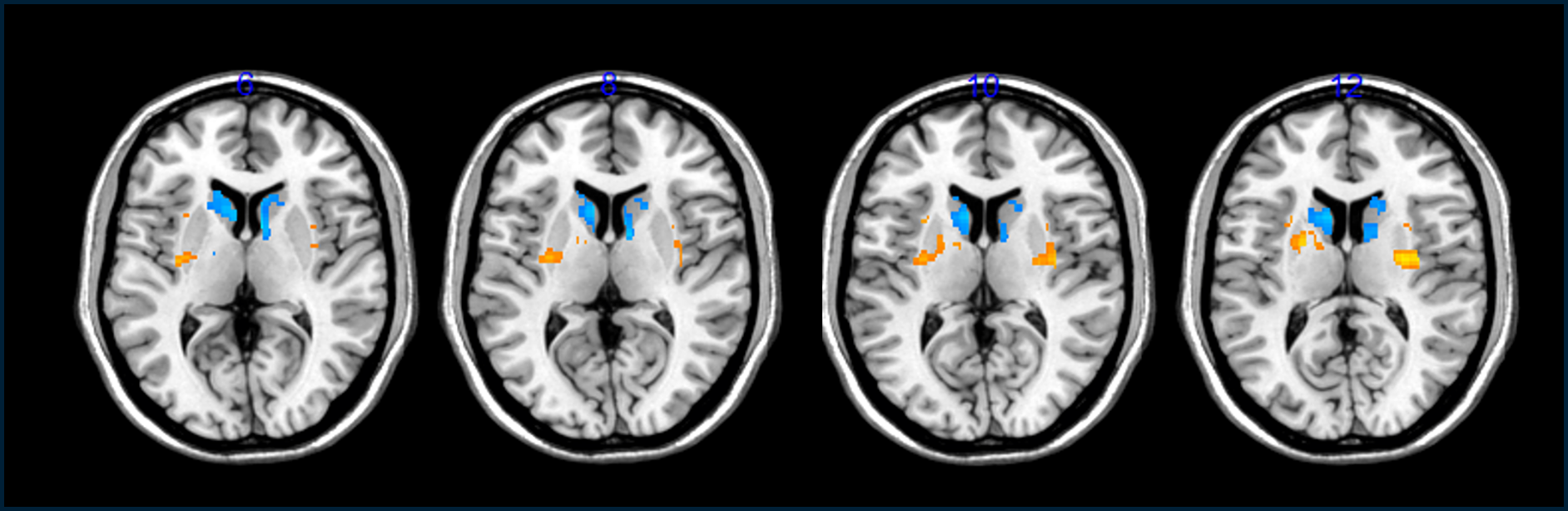

These clues that the transplants helped came from brain scans that showed an increase in dopamine cells in the patients’ brains as well as a decrease in “off time,” or the number of hours per day the volunteers felt they were incapacitated by their symptoms.

However, outside experts expressed caution in interpreting the findings, saying they seemed to show inconsistent effects—some of which might be due to the placebo effect, not the treatment.

“It is encouraging that the trial has not led to any safety concerns and that there may be some benefits,” says Roger Barker, who studies Parkinson’s disease at the University of Cambridge. But Barker called the evidence the transplanted cells had survived “a bit disappointing.”

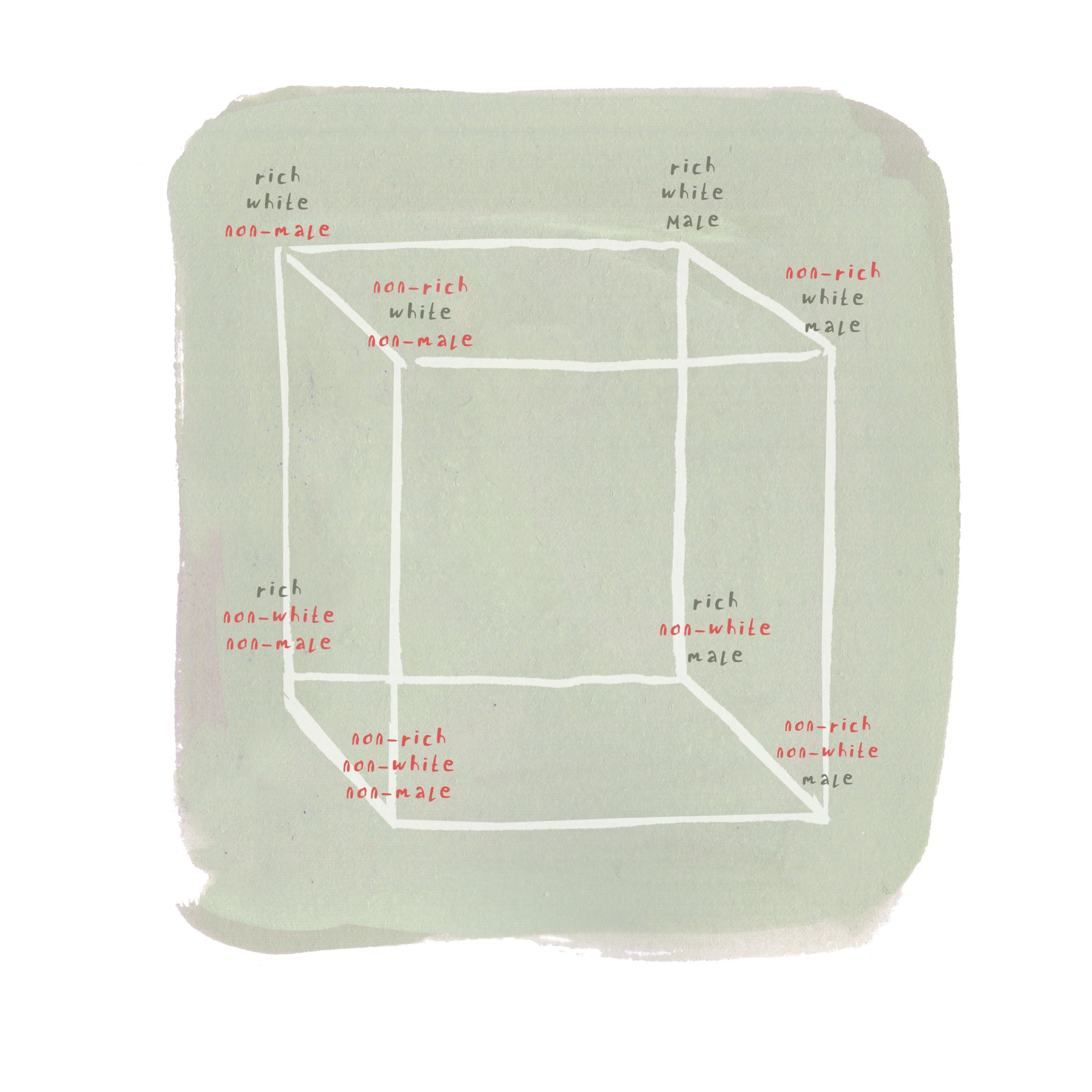

Because researchers can’t see the cells directly once they are in a person’s head, they instead track their presence by giving people a radioactive precursor to dopamine and then watching its uptake in their brains in a PET scanner. To Barker, these results were not so strong and he says it’s “still a bit too early to know” whether the transplanted cells took hold and repaired the patients’ brains.

Legal questions

Embryonic stem cells were first isolated in 1998 at the University of Wisconsin from embryos made in fertility clinics. They are useful to scientists because they can be grown in the lab and, in theory, be coaxed to form any of the 200 or so cell types in the human body, prompting attempts to restore vision, cure diabetes, and reverse spinal cord injury.

However, there is still no medical treatment based on embryonic stem cells, despite billions of dollars’ worth of research by governments and companies over two and a half decades. BlueRock’s study remains one of the key attempts to change that.

And stem cells continue to raise delicate issues in Germany, where Bayer is headquartered. Under Germany’s Embryo Protection Act, one of the most restrictive such laws in the world, it’s still a crime, punishable with a prison sentence, to derive embryonic cells from an embryo.

What is legal, in certain circumstances, is to use existing cell supplies from abroad, so long as they were created before 2007. Seth Ettenberg, the president and CEO of BlueRock, says the company is manufacturing neurons in the US and that to do so it employs embryonic stem cells from the original supplies in Wisconsin, which remain widely used.

“All the operations of BlueRock respect the high ethical and legal standards of the German Embryo Protection Act, given that BlueRock is not conducting any activities with human embryos,” Nuria Aiguabella Font, a Bayer spokesperson, said in an email.

Long history

The idea of replacing dopamine-making cells to treat Parkinson’s dates to the 1980s, when doctors tried it with fetal neurons collected after abortions. Those studies proved equivocal. While some patients may have benefited, the experiments generated alarming headlines after others developed “nightmarish” side effects, like uncontrolled writhing and jerking.

Using brain cells from fetuses wasn’t just ethically dubious to some. Researchers also became convinced such tissue was so variable and hard to obtain that it couldn’t become a standardized treatment. “There is a history of attempts to transplant cells or tissue fragments into brains,” says Henchcliffe. “None ever came to fruition, and I think in the past there was a lack of understanding of the mechanism of action, and a lack of sufficient cells of controlled quality.”

Yet there was evidence transplanted cells could live. Post-mortem examinations of some patients who’d been treated with fetal cells showed that the transplants were still present many years later. “There are a whole bunch of people involved in those fetal-cell transplants. They always wanted to find out—if you did it right, would it work?” says Jeanne Loring, a cofounder of Aspen Neuroscience, a stem-cell company planning to launch its own tests for Parkinson’s disease.

The discovery of embryonic stem cells is what made a more controlled test a possibility. These cells can be multiplied and turned into dopamine-making cells by the billions.

The initial work to manufacture such dopamine cells, as well as tests on animals, was performed by Lorenz Studer at Columbia University. In 2016 he became a scientific founder of BlueRock, which was initially formed as a joint venture between Bayer and the investment company Versant Ventures

“It’s one of the first times in the field when we have had such a well-understood and uniform product to work with,” says Henchcliffe, who was involved in the early efforts. In 2019, Bayer took full control of the stem-cell company in a deal valuing it at around $1 billion.

Movement disorder

In Parkinson’s disease, the cells that make dopamine die off, leading to shortages of the brain chemical. That can cause tremors, rigid limbs, and a general decrease in movement called bradykinesia. The disease is typically slow-moving, and a drug called levodopa can control the symptoms for years. A type of brain implant called a deep brain stimulator can also reduce symptoms. The disease is progressive, however, and eventually, levodopa can’t control the symptoms as well.

This year, the actor Michael J. Fox confided to CNN that he retired from acting for good after he couldn’t remember his lines anymore, although that was 30 years after his diagnosis. “I’m not gonna lie. It’s getting harder,” Fox told the network. “Every day it’s tougher.”

The promise of a cell therapy is that doctors wouldn’t just patch over symptoms but could actually replace the broken brain networks by adding new neurons.

“The potential for regenerative medicine is not to just delay disease, but to rebuild brain functionality,” says Ettenberg, BlueRock’s CEO. “There is a day when we hope that people don’t think of themselves as Parkinson’s patients.”

Ettenberg says BlueRock plans to launch a larger study next year, with more patients, in order to determine whether the treatment is working, and how well.