Frans Francken the Younger, Chamber of Art and Curiosities, 1636. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Unicorn horns, mermaid skeletons, taxidermied animals, preserved plants, clocks, scientific instruments, celestial globes: These were the contents of the Wunderkammer, or cabinets of curiosities, that became fashionable throughout royal and aristocratic homes across Europe in the

and

periods—a time in history when man aspired to know everything as the effects of worldwide exploration and scientific experimentation became more accessible.

Today, we use the term loosely to describe any fascinating or idiosyncratic accumulation of objects secreted away in boxes or behind closed doors. The Wunderkammer’s original definition in the Renaissance was more specific. It signified a diverse, carefully constructed collection of both art and natural and man-made oddities that embodied the era’s thirst for exploration and knowledge, and laid the groundwork for museums as we know them today.

Domenico Remps, Cabinet of Curiosities, ca. 1690. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Directly translated as “wonder chamber,” the word “Wunderkammer” first appeared in the mid-1500s, when Johannes Müller and Count Froben Christoph included it in their 1564–66 tome chronicling the lives of the noble Zimmern family. Simultaneously, in 1565, Samuel Van Quiccheberg penned what’s considered to be the inaugural guide to collecting, preservation, and display; he based the text on his experience as the scientific and artistic adviser to the Duke of Bavaria, whose Wunderkammer he helped amass.

According to Quiccheberg, their contents fell under a variety categories like artificialia, man-made antiquities and artworks; naturalia, plants, animals, and other items from nature; scientifica, scientific instruments; exotica, objects from distant lands; and mirabilia, a bucket term for other marvels that spark wonder.

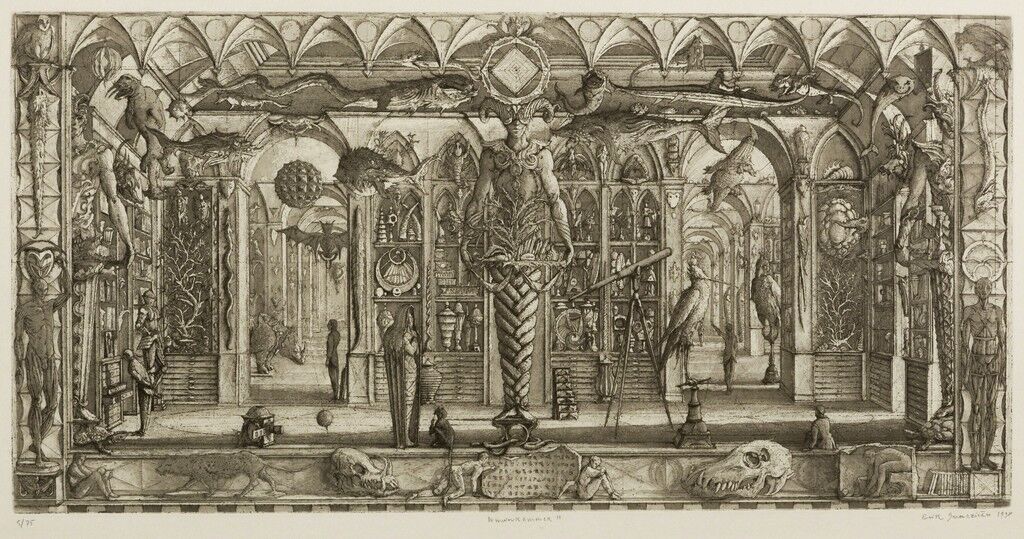

Plucked from many corners of the globe, these objectsrepresented a vast swath of art, science, and mysticism—what Quiccheberg called a “theater of the world.” In the words of contemporary scholar Patrick Mauriès, the Wunderkammer attempted to capture “all knowledge, the whole cosmos arranged on shelves.” Some were as small as cabinet, others as vast as labyrinth of large rooms.

While ferreting away strange and wondrous objects “had been part of human evolution since time immeasurable,” as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Wolfram Koeppe has pointed out, this process of collecting flourished during the Renaissance. The 13th-century invention of the compass and subsequent enhancements in cartography sparked an explosive period of exploration and global trade in the 1500s and 1600s. In this “Age of Exploration,” leaders across Italy, Spain, and England sent explorers around the globe to search for new territories and a deeper knowledge of the world.

At the same time, science became a defined discipline that sought to answer big questions about the earth, the heavens, and the human body. While the Catholic Church attempted to prohibit scientific research—a threat to the theories put forth in biblical texts—volumes detailing medical discoveries and the structure of the cosmos were being published in droves. Similarly, artists like

eschewed religious subject matter in favor of representing the natural world and accurate human anatomy.

Engraving frm Ferrante Imperato, Dell’Historia Naturale, 1599. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Wunderkammer resulted from this voracious period of travel, colonization, and scientific and artistic development as a tool to explore and contemplate this growing cache of knowledge from the comfort of one’s own home. In his Naples abode, Italian aristocrat and apothecarian Ferrante Imperato assembled a dense, legendary Wunderkammer said to have boasted as many as 35,000 plant, animal, and mineral specimens.

Ferrante was also one of the first to depict a cabinet of curiosities, in the frontispiece of the 1599 catalogue of his collection, Dell’historia natural. The woodcut shows four pantalooned men surrounded by all manner of curiosities, carefully arranged in an intricate honeycomb of drawers, shelves, and display cases. The contents spill onto the ceiling, where a menagerie of stuffed fish, salamanders, and seashells are pinned strategically around what looks like his prized possession: a massive taxidermied alligator.

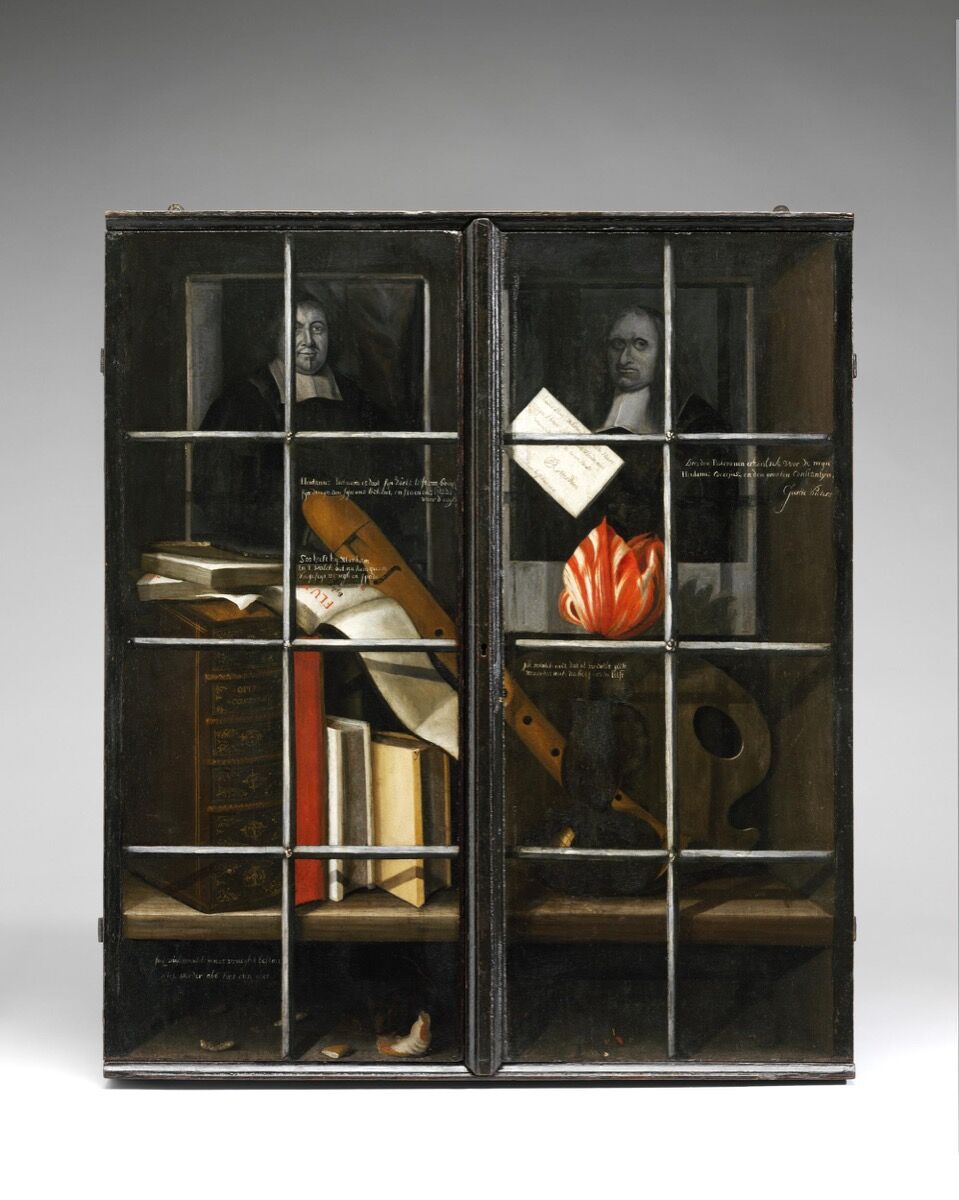

Cupboard by an unknown artist, 1678–80. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Unknown

Renaissance Mortar, North Italian, probably Turin, ca 1560

Collections like these operated as an ordered microcosm of the wider world, as well as a platform for people of the Renaissance to satisfy their craving for wonder-inducing experiences. The Wunderkammer was not “an end in itself so much as a source of endless beginnings,” historian Earle Havens wrote, “a cabinet-sized microcosm of the endless, divinely created macrocosm whose wonders never cease.”

Most Wunderkammer, though, weren’t meant to be purely scientific—they were also places to explore personal tastes, indulge mysticism, and demonstrate power. Beyond objects extracted directly from nature, typical cabinets of curiosity contained sculptures, paintings, books, coins, medallions, precious gems, maps, and scientific instruments.

They also housed objects representing mysticism and the occult: stones said to be magical; horns supposedly belonging to unicorns; enchanted creatures meant to be mandrakes and mermaids (made by sewing together the torso of a monkey and the tail of a fish). “Every object offered an opportunity to tell a story about an epic adventure or, more often, to fabricate one,” wroteart historian Giovanni Aloi.

The flexibility of the Wunderkammer to toggle between nature and art, between the real and the imagined, allowed collectors to present their own versions of the world, sometimes to their political advantage. Royal cabinets of curiosity were often situated near parade rooms, where they could be flaunted when important visitors—and rivals—came to call.

The breadth of a collection signified its owner’s intelligence, wealth, taste, and business prowess. “Standing at the center of this mini-universe and pointing at the objects to disclose their deepest secrets, collectors felt a sense of ease and mastery over a world that most often appeared too big, too confusing, and too inhospitable,” Aloi continued.

Emperor Rudolf II was known to possess eclectic collecting tastes, to say the least. If you had secured an invitation to his opulent Prague Castle in the late 1500s, you might have been treated to a tour of his cache of treasures, which contained everything from magical stones, celestial globes, and astrolabes to masterpieces by the likes of

,

, and

. Rudolf II’s trove was renowned throughout Europe, hailed as the era’s most comprehensive and wondrous Wunderkammer.

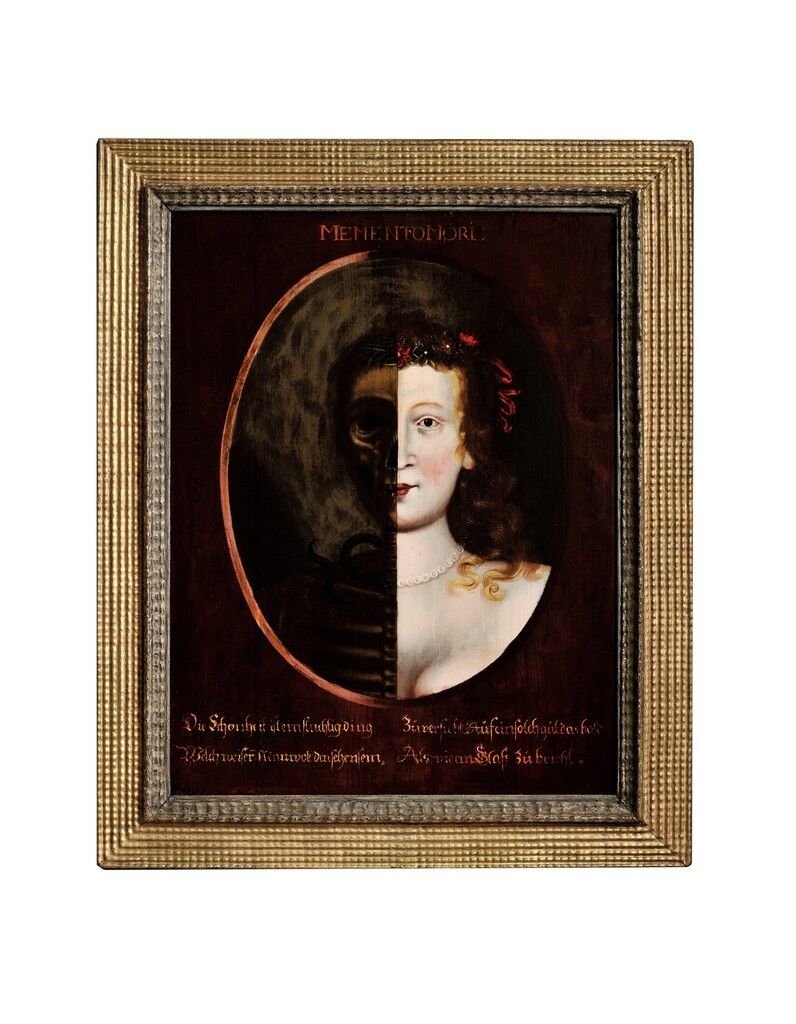

Daniel Preisler

Memento Mori Painting, Nuremberg-ca 1650

Gerhard Emmoser, Celestial globe with clockwork, 1579. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rudolf II showed off his treasures on a regular basis as a means of exercising soft power, but he also spent countless hours within it, poring over the world and its wonders. His multi-room cabinet of wonders, containing both natural oddities and artistic masterpieces, not only represented his own passions and power, but also “the broader scientific and artistic interests of the court,” as scholar Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann has noted.

The emperor’s heaping—albeit organized—Wunderkammer harnessed the tastes and cultural proclivities of his time. Based on personal tastes and the desire to harness and concentrate knowledge, this collection and other Wunderkammer went on to influence how both private and public collections would be organized in the future. But while the Wunderkammer made way for the encyclopedic collections of institutions like the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum in New York, they also emphasized a myopic European, moneyed perspective, which has only begun to be reassessed in the last several decades.

Alexxa Gotthardt is a contributing writer for Artsy.