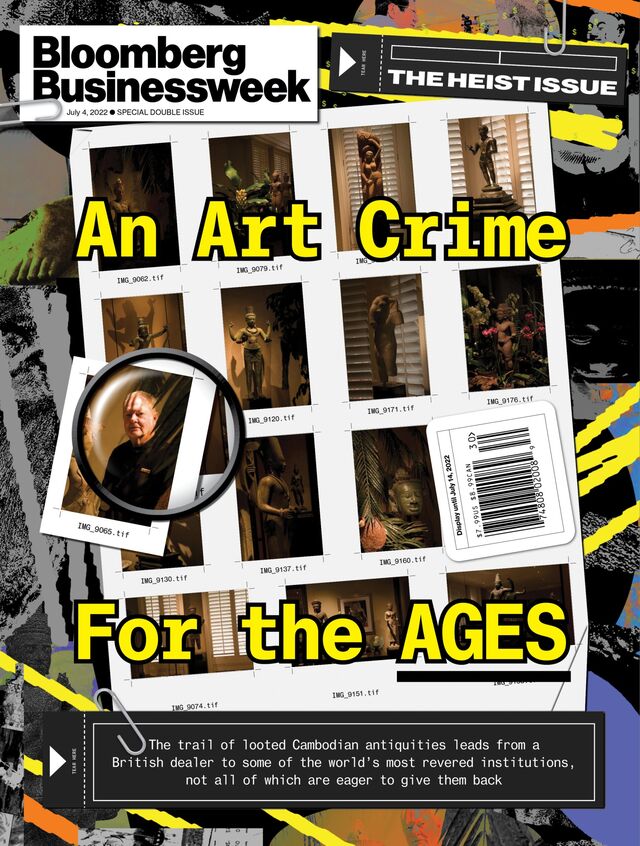

Deep in the Cambodian jungle, investigators are unraveling a network that trafficked antiquities on an unprecedented scale and brought them all the way to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The looters arrived late in the afternoon at Koh Ker, a ruined 10th century city in northern Cambodia. They made their way through scrubby jungle to Prasat Krachap, a compact stone temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva and his son Skanda. They walked carefully. The countryside was strewn with land mines, and on another expedition some of the looters had watched a wandering cow be blown up.

The leader of the band, a muscular man named Toek Tik, had selected Prasat Krachap carefully. As a boy, he’d been forced by the Khmer Rouge to serve as a child soldier. He escaped in the mid-1970s, disappearing into the forested slopes of a nearby mountain. While on the run he built up an intimate knowledge of ancient sites, sometimes using temples as shelters. This one, he thought, was particularly promising.

It was the autumn of 1997, near the end of 30 years of civil conflict in Cambodia. The men with Toek Tik were all marked by the violence. Some had fought, like him, with the Khmer Rouge, the genocidal communist party that had held the country from 1975 to 1979. Many were enmeshed in the subsequent contests for political control, which pitted what remained of the Khmer Rouge against more moderate socialists and forces allied with the Cambodian royal family.

The looters began digging in Prasat Krachap’s central shrine, attentive to the jolt of a shovel hitting stone instead of dirt. Eventually the contours of several humanlike figures emerged. The men kept digging through the night, exposing enough of the objects to haul them out using pieces of wood as levers. One of the sculptures, about three and a half feet tall, depicted Shiva, his lips in a hint of a smile, sitting cross-legged across from Skanda, who was rendered as a small boy extending his hands upward to clasp his father’s. Another statue of about the same height showed Skanda in his adult role as a god of war, sitting astride Paravani, a thick-bodied peacock, carved in such detail that each feather was distinct. Toek Tik and his men were probably the first people in centuries to lay eyes on these works.

They loaded the artifacts onto oxcarts, straining to lift the heavy stone. After days of travel on rutted country roads, they would transfer them to an antiquities broker near the Thai border. Each looter would receive about 15,000 Thai baht, a little over $400. From the border, The Peacock and Skanda and Shiva, as the two statues became known, made their way into the hands of a Bangkok-based British businessman named Douglas Latchford. Not long after receiving The Peacock, Latchford sold it to a collector for $1.5 million. Skanda and Shiva became part of his own trove of statues.

For more than 40 years, Latchford was the world’s foremost dealer of Cambodian antiquities. An energetic salesman, he invigorated a once-sleepy corner of the art market, securing seven-figure prices for objects that previously had modest commercial value and landing them in the collections of institutions including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Today his activities are at the center of one of the most complex art market investigations ever undertaken. Government officials and lawyers in the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, academics in Paris, heritage advocates in Washington, and federal prosecutors in New York City are all involved, trying to unravel what they consider an historic crime: the theft of Cambodia’s archaeological treasures in a campaign of plunder that continued until almost the end of the 20th century.

Thousands of pieces were taken, robbing Cambodians of relics that some view almost as physical manifestations of their ancestors. Ripped from their pedestals with picks, chisels, and even dynamite, and sometimes broken into parts for easier transport, these artifacts were dispersed around the world, repurposed to adorn museum halls and living rooms in New York, London, and Palm Beach. The investigators are working to track down and repatriate what Latchford sold, a project that has only accelerated since he died in 2020 at age 88, before he could face federal fraud and conspiracy charges.

Latchford didn’t loot ancient sites himself, and it’s unclear whether he ever had direct contact with those who did. Some of his fellow dealers argue he’s been unfairly vilified for operating in a system that he appeared to genuinely believe was ethical. Concern with the origin of ancient works is a relatively recent phenomenon, as they point out, and it wouldn’t be wrong to say that when Latchford began collecting and selling Cambodian antiquities, almost no one he interacted with would have cared where they came from. Artifacts from poor, previously colonized countries were simply viewed as fair game.

But to those trying to understand Latchford’s life and work, none of those caveats diminished his responsibility—rather, his unique position made him more culpable. Tess Davis, the executive director of the Antiquities Coalition, a Washington-based group that combats trafficking in artifacts, once described Latchford as a “Janus,” for the two-faced Roman god: oriented on one side to an underworld of temple robbers and smugglers and on the other to wealthy collectors and elite museums. Without someone to move objects between the two, the business model of antiquities theft would fall apart.

“He was one of the principal organizers of the mass looting of Cambodia in the second half of the 20th century,” Ashley Thompson, a professor of Southeast Asian art at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, who worked on Cambodian reconstruction projects during the 1990s, said in an interview. “It was an open secret. It was an awful, awful thing to be doing, and we knew there was a man in Bangkok who was doing it.”

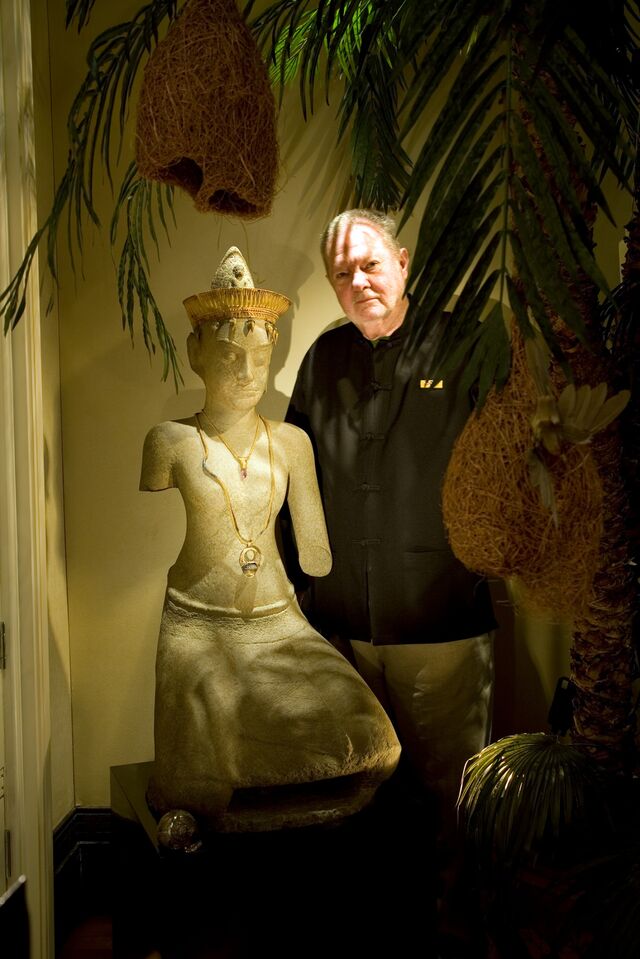

On the back flap of Adoration and Glory, a major catalog of Cambodian artifacts Latchford published in 2004, he described himself as an “adventurer-scholar.” The truth was more prosaic. Partial to elegant suits, five-star hotels, and first-class travel, Latchford didn’t spend much time trooping through jungles in search of lost treasures. Born in British-ruled Bombay, where his father managed a bank, he’d come to Thailand in the mid-1950s, working for a company that imported cosmetics, chemicals, and other goods, eventually focusing on the pharmaceutical business. Latchford would later say he’d been at a dinner party hosted by an art adviser to the tobacco heiress Doris Duke when he saw his first statue from Cambodia. The moment changed his life. “Greek and Roman sculpture is wonderful, but I responded to this on another level,” he told an interviewer for Apollo magazine. Latchford immediately bought a piece of his own, for just 18,000 baht, then another, then many more.

He was hooked even before his first trip to Angkor, in 1961. The ancient city was the capital of the Khmer Empire, which by the 12th century encompassed present-day Cambodia as well as much of Thailand and Vietnam. Its rulers were heavily influenced by Hinduism—it wasn’t until after the 1200s that Theravada Buddhism became Cambodia’s dominant religion—and they demonstrated their power by commissioning ever-grander temples and religious statuary, carved in stone or cast in bronze by corps of artisans. Angkor represented the height of the Khmer kings’ ambitions, and it’s hard to imagine what it must have been like for Latchford to experience the site as it was when he first saw it: remote, overgrown, and almost devoid of visitors, a window into a lost world of heroic warriors and deep religious belief.

In Bangkok, Latchford accelerated his acquisitions, enabled by the growing success of a drug company he founded and, later, investments in the city’s booming real estate market. His collecting inspired comparisons to a man he admired: Jim Thompson, the swashbuckling American spy who became a noted connoisseur of Asian art before he disappeared without a trace in 1967, earning a permanent place in Bangkok lore. By the mid-1970s Latchford qualified as a significant collector and dealer, sometimes working in collaboration with Spink, a London auction house later acquired by Christie’s. His condominium, in a building he’d developed himself in the heart of the Thai capital, was essentially a museum of Khmer statuary. There he welcomed a steady stream of brokers offering artifacts for sale, some of them freshly obtained from runners who’d brought objects across the border. He kept more pieces in his second home, a luxurious apartment in London’s Mayfair district.

Meanwhile, Latchford was developing a hobby: funding the operations of the Thai national bodybuilding association. He served for a time as its president and played “a vital part in Thailand winning many gold medals” at international competitions, according to current head Sugree Supawarikul. As a result, Latchford was surrounded for much of his life by a shifting cast of young Thai bodybuilders. Although he had a brief marriage to a Thai woman with whom he had a daughter, Julia, he became more open about his sexuality over time, and some of the bodybuilders may have been his lovers. Others served as drivers or personal assistants, sometimes trusted with traveling to the Cambodian border to examine statues being offered for sale. In the Bangkok Post, Latchford boasted that his “bodybuilder chef” had won a gold medal for his class at the Asian championships. Latchford was “a visual man,” a longtime friend told me, asking not to be identified because of the stigma of being associated with him. For some of the same reasons Latchford was drawn to Khmer artworks, “he just liked to have these guys around to look at.”

For much of Latchford’s adult life, the country whose heritage obsessed him was effectively off-limits. A civil war began in Cambodia in 1967, culminating with the victory of the Khmer Rouge eight years later. Their leader, Pol Pot, used his newfound power to initiate one of the darkest periods of the 20th century. Agriculture was collectivized, leading to widespread famine, while residents of cities were marched into the countryside and forced to work under slavelike conditions. Militants targeted anyone suspected of connections to capitalism or foreign cultures or of deviating from the Khmer Rouge’s extreme interpretation of Marxism. More than 1.5 million people were killed. The party’s rule ended in 1979, when invading Vietnamese forces installed a proxy government that restored a degree of normality. But the Khmer Rouge continued to fight, launching a stubborn insurgency.

Archaeologists and collectors couldn’t easily visit the Cambodian countryside, which was strewn with millions of land mines. Looters who knew the terrain could operate more easily, particularly after the violence wound down in the 1990s. Today, trafficking experts view the period as something of a golden age for antiquities theft. Looting was so widespread that the Conservation d’Angkor, a storehouse of artifacts in Siem Reap, Cambodia’s second city, was attacked at least three times. On one occasion, a group of as many as 300 raiders took 31 statues, killing a guard in the process. While Angkor Wat and its environs were eventually secured, few other temples were, and thieves secreted thousands of Khmer objects out of the country, leaving shattered pedestals and empty alcoves.

For Cambodians, the cultural damage was immense. “When I see the stone destroyed, I ask the question, ‘What kind of greed and ignorance would drive someone to destroy this?’ ” said Phoeurng Sackona, Cambodia’s minister of culture and fine arts, who’s been closely involved in efforts to track down stolen objects. “But at the same time, I need to understand the situation.” Decades of conflict had devastated the economy, and there were few legitimate job opportunities. The international market for Khmer antiquities was robust, creating incentives for theft that were hard for some to resist.

Stability finally returned in the early 2000s under the authoritarian leadership of Hun Sen, a onetime Khmer Rouge soldier who’d switched sides, serving in the Vietnamese-backed government of the 1980s before prevailing in the power struggles that followed. (Hun Sen remains prime minister today, leading a government that human-rights groups condemn for intense repression of political opponents.) Cambodia was growing more accessible, as long as you didn’t wander unescorted in heavily mined rural areas, and Latchford became a regular visitor. In 2002 he made a trip to Koh Ker, helicoptering in with Emma Bunker, a Colorado-based researcher with whom he worked closely.

The site was the Khmer Empire’s capital for less than 20 years, a brief pause in the dominance of Angkor. But during that time, Koh Ker’s sculptors developed a style distinct from the stoic, angular statues seen in other Cambodian sculpture. Their figures are almost sensual, with full lips set in expressive faces. Some are depicted in motion, as though they might leap from their pedestals at any moment. Latchford found them captivating and bought them when he could. Some he sold to wealthy collectors, such as Netscape co-founder James Clark, who spent $35 million on more than 30 pieces from Latchford. Investigators believe that others ended up in the Palm Beach home of the pipeline tycoon George Lindemann. (Lindemann died in 2018; his son didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

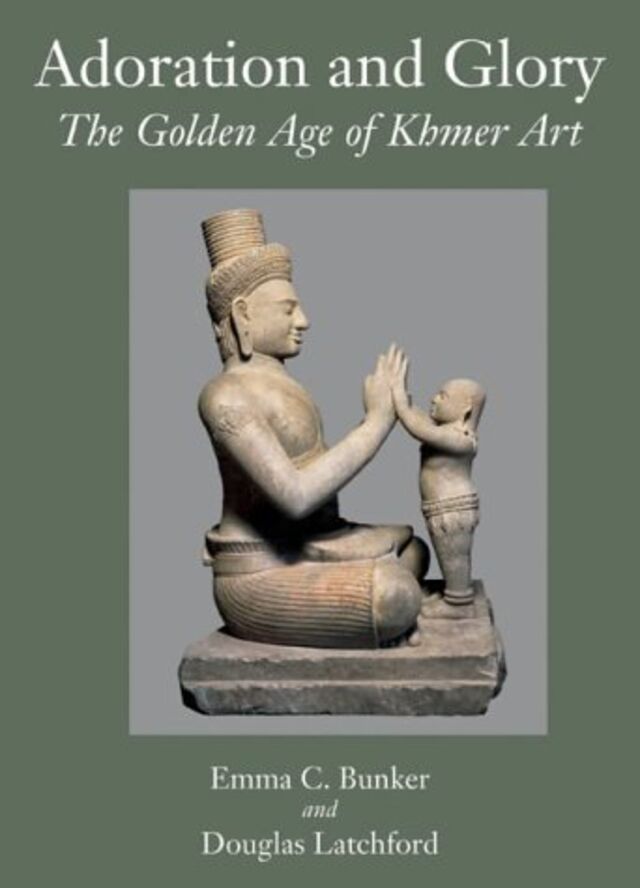

Adoration and Glory, which Latchford co-wrote with Bunker, hinted at just how many significant Cambodian statues had passed through his hands. The book featured finely staged photographs of almost 200 works, largely resident in Western museums or private collections; many, it appeared, either belonged to Latchford or had moved through his operation at some point. It also included forewords from three of Cambodia’s most senior cultural officials, whom he’d cultivated by donating money to spruce up the National Museum in Phnom Penh. One of the officials, the museum’s then deputy director, Hab Touch, marveled at the breadth of what Latchford had assembled. “The first time I saw the photographs,” he wrote, “I realized that while I work with Khmer art every day I had only been familiar with a small proportion of what exists.”

In 2007 a British stone expert named Simon Warrack was working at Koh Ker, collecting data for potential conservation efforts. As he walked around Prasat Chen, one of the ancient city’s major temples, he spotted a pair of upright stone feet on the ground. Warrack was intrigued enough to take some photos, but he didn’t give much more thought to the find.

Not long afterward, in a library in Siem Reap, he came across Adoration and Glory. “Suddenly, turning over the page, and there was this big, huge statue with no feet,” Warrack told me. “It tripped something in my mind.” The statue, a spectacular 5-foot-tall “temple guardian,” was listed as belonging to the Norton Simon Museum in California. Warrack took a photo of the page, then merged it in Photoshop with a picture of the feet from Koh Ker. “It fitted at all three points,” he said, “which is more than a coincidence … there was absolutely no doubt.”

By leaving the feet behind, looters had allowed Warrack to locate a crime scene: the spot from which one of the most significant Khmer statues in any foreign collection had been hacked away. He wrote a memo that was sent to Unesco, the United Nations agency responsible for cultural heritage and the overseer of a 1970 treaty, accepted by more than 100 countries, that lets governments demand the return of objects removed without authorization after it entered into force. Warrack suggested that a more detailed investigation was in order, but Unesco’s efforts didn’t get very far.

Coincidentally, Eric Bourdonneau, a French archaeologist who has conducted some of the most detailed research at Koh Ker, was interested in the same pair of feet as Warrack and another pair found just inches away. Bourdonneau believed the Norton Simon statue, which had been in its collection since the 1970s, to be a representation of Bhima, a protagonist of the Mahabharata, the Sanskrit epic. That meant the other feet probably belonged to Duryodhana, a warrior who fights Bhima in one of the poem’s key battles. But Bourdonneau had no idea where that Duryodhana statue had gone. So he was astonished when he saw the promotional materials for an auction that Sotheby’s was holding in New York in the spring of 2011. They showed a 5-foot-tall stone warrior in the distinctive Koh Ker style—the Duryodhana. It had been purchased in the 1970s by a Belgian businessman and been consigned for sale by his widow, with an estimated price of as much as $3 million.

At the time, attitudes toward the origins of artworks in international collections were in flux. Prompted by demands for the restitution of pieces stolen by the Nazis, museums and auction houses had by the 1990s begun to require more detailed provenance information, ideally establishing a full chain of ownership. In theory, 1970, the year of the Unesco treaty, was considered a cutoff for dealing in objects such as Cambodian statues. If a seller couldn’t prove that an artifact was abroad earlier or that a home government had granted explicit permission for its removal, its sale would be illegitimate. In practice, that constraint was sometimes ignored, particularly for works from poor countries without the resources to press their claims. In a 2011 study, the Antiquities Coalition’s Davis analyzed 377 Khmer pieces put up for auction at Sotheby’s from 1988 to 2010. She found that 71% had no published provenance; for the rest, the information was often fragmentary.

Still, some law enforcement agencies were beginning to take a closer interest in looted art, among them the Department of Homeland Security, which has jurisdiction over imports to the US. After Bourdonneau sent Unesco a report identifying the Sotheby’s warrior as the lost Duryodhana, DHS agents contacted the auction house, warning that the statue could be stolen property. The piece was pulled the same day it was supposed to go on the block—though Sotheby’s head of compliance at the time, Jane Levine, said in a letter to Unesco that she was confident the Duryodhana was out of Cambodia prior to 1970 and that Sotheby’s and its client didn’t intend to repatriate it. If the Cambodian government wanted it back, it was welcome to “purchase the sculpture in a private sale.”

Federal prosecutors in New York disagreed with Sotheby’s claims. They launched a forfeiture action, which allows the government to seize property it believes is linked to illegal activity, and demanded that the auction house relinquish the Duryodhana so it could be returned to Cambodia. The prosecutors ultimately claimed it had been looted in the early 1970s and would have been protected by Cambodian law even before that date. After being taken out of the country, they said, the Duryodhana and its counterpart, the Norton Simon’s Bhima, were “obtained by a well-known collector of Khmer antiquities” who knew they’d been stolen from Koh Ker. “The collector then attempted to sell [the Duryodhana] on the international art market,” consigning it to a British auction house, which ultimately found the Belgian buyer.

It was clear to anyone with the relevant background that the “collector” was Latchford. He told the New York Times that the prosecutors were mistaken, saying he’d never actually owned the Duryodhana. Yet whatever his connections to that specific object, he was on the radar of US law enforcement in a way he’d never been before.

When, in 2012, the US Department of Justice needed to hire a consultant in Cambodia for the Duryodhana case, the natural choice was Brad Gordon. The head of a firm that worked with investors trying to get a piece of the country’s economic revival, Gordon was one of a tiny number of internationally connected attorneys in Phnom Penh. The American prosecutors wanted him to supplement evidence of the theft that they were accumulating through corporate records and interviews in the US. Intrigued by the challenge, Gordon began driving around the Koh Ker region with a translator, looking for people who remembered the Duryodhana being removed. He eventually found a few, including a man who said he’d seen it on an oxcart in 1972, when he was a teenager. The man said the date was fixed in his mind because he’d been involved in a love affair with a girl from another village who was later killed by the Khmer Rouge.

This witness had become the caretaker of a Buddhist temple not far from the Koh Ker ruins, and Gordon visited periodically, hoping to find older residents who might be willing to talk. There, he was directed to another local man, who supposedly knew a great deal about ancient sites. Gordon didn’t get an exact address for him, just a name and a general location, so he went door to door with his translator. At perhaps the sixth house, a woman answered the door and confirmed that the person Gordon was looking for was inside. The translator told a white lie, claiming Gordon wanted to discuss buying land in the area—and also happened to be interested in antiquities. Gordon was invited in and introduced to a middle-aged man. His name was Toek Tik.

After they started talking, Gordon pulled out a copy of Adoration and Glory. When Toek Tik saw the book, which had an image of Skanda and Shiva on the cover, his face lit up in excitement. “I know this, I know this!” he exclaimed, calling his wife over. He flipped through the pages, smiling with recognition.

Toek Tik was cagey about how he’d become so familiar with Khmer Empire statuary, but Gordon had his suspicions. After some guarded conversation, he and the translator departed, promising to keep in touch about the antiquities in the book. “We didn’t realize until years later,” Gordon told me, “that he’d stolen so many of them.” They met a couple more times, Toek Tik gradually revealing more of his past. But he seemed too young to have been involved with the Duryodhana theft, which was Gordon’s priority.

The case back in New York was gathering momentum. In May 2013 the Metropolitan Museum agreed to return the Kneeling Attendants, a pair of sandstone figures flanking the entrance to its Southeast Asian galleries, after Cambodian officials presented evidence that they’d been taken from the same location at Koh Ker as the Duryodhana. Later that year, Sotheby’s abandoned its effort to hold on to the Duryodhana itself, agreeing with prosecutors to repatriate the statue. Within months the Norton Simon said it would return the Bhima, too. All would be put on display in Cambodia’s National Museum.

In the antiquities community, Latchford was becoming indelibly associated with the looting of Koh Ker. In addition to his apparent role in the Duryodhana sale, he’d donated both the torsos and one of the heads of the Kneeling Attendants to the Met. Some curators and dealers had grown wary of doing business with him, and heritage activists started referring to him with a derisive nickname: “Dynamite Doug,” for the rumored means by which his statues were removed from temples.

Aware that his reputation was at risk, Latchford opened informal talks about returning some part of his personal collection to Cambodia. The Cambodians quickly concluded that he wasn’t serious. “He was quite defensive at that time,” recalled Kong Vireak, a former National Museum director who was involved in the discussions. “The first request from him was for the government of Cambodia to make a public declaration that he was clean. He would do a small return, maybe three objects. And we said, ‘No, not fair.’ ”

At the same time, Latchford kept making sales. One client was Harald Link, a Thai-German businessman who leads B. Grimm Group, one of Thailand’s largest conglomerates. In emails from the period viewed by Bloomberg Businessweek, Latchford peppered Link with sales pitches for statues. The messages seldom mentioned provenance; instead, Latchford focused on aesthetics, sometimes in slightly creepy terms. “Just look at that mouth,” he wrote in 2016 of one statue, a bare-breasted woman. “But not before just going to bed, you will dream of her all night!!!”

According to a sales invoice from 2018, Link paid 30 million baht—about $870,000—for a 4-foot-tall stone sculpture of a kneeling Khmer queen, which Latchford dated to the 12th or 13th century. A document from the following year recorded the sale to Link of another kneeling female figure, this time in bronze, her palms pressed together as though in prayer. (In an interview, Link said he was unaware of the allegations against Latchford at the time of the transactions.)

DHS agents and prosecutors kept drawing closer to Latchford. Just before Christmas 2016, a prominent Manhattan antiquities dealer, Nancy Wiener, was arrested on charges of possessing stolen property. Wiener’s late mother, Doris, had been the grande dame of New York’s Asian art scene, and her Upper East Side gallery was one of the city’s best sources for ancient works. The criminal complaint against Wiener indicated that prosecutors viewed her as part of a larger network, describing interactions with “Co-Conspirator #1,” who was clearly Latchford, and “Co-Conspirator #2,” who was clearly his longtime collaborator Emma Bunker. According to the complaint, both had worked with Wiener to falsify provenance information.

Latchford was in declining health, suffering from Parkinson’s disease and heart problems. He could no longer travel easily and needed help from nurses with even basic tasks. In a 2018 memo to the US ambassador in Phnom Penh, Gordon—who was now advising the Cambodian government on its discussions with Latchford—explained that the dealer’s advancing age and fear of prosecution opened “a rare and perhaps singular opportunity” to get back a huge collection of stolen antiquities. In exchange, Latchford wanted assurances he wouldn’t face US charges and, if possible, a similar guarantee for Bunker. (Bunker died in 2021, and her children didn’t respond to requests for interviews about her work with Latchford.)

Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture was willing to request leniency for Latchford from the US, as long as he returned everything he owned and provided detailed information about past sales. But he was a mercurial negotiating partner, according to several people involved. One day, he might seem willing to hand everything over. The next, he would change his mind, insisting he was willing to part with only a few statues.

Seeking leverage, Gordon began making regular trips to meet with Toek Tik, securing a promise from the government that he wouldn’t be prosecuted for what he revealed. Over dozens of meetings, Toek Tik recounted a prolific career as a looter. He’d entered the business in the 1980s, working initially on his own and with little knowledge of what to steal or how to sell it. Gradually he built a loose network of hundreds of men who could be called upon to uproot artifacts and move them toward the border. There, Toek Tik would pass the objects to one of a few brokers, who’d get them into Thailand. He estimated that he’d taken more than a thousand pieces, developing a working knowledge of major Khmer Empire styles. When Gordon asked who ultimately bought them, Toek Tik answered without hesitation: The top buyer was a foreign collector in Bangkok, “Sia Ford”—Latchford. (Sia is a Thai term for a wealthy businessman.)

Gordon was never able to put Toek Tik’s account to Latchford. In the summer of 2019 Latchford’s health deteriorated rapidly, and he was soon in intensive care at Bumrungrad hospital in Bangkok. He was still there, intubated and barely able to communicate, when the indictment he’d feared was unsealed. In the document, US prosecutors finally stated what earlier legal filings had suggested: that Latchford had “engaged in a scheme to sell looted Cambodian antiquities on the international art market,” falsifying the origins of statues to effectively launder them into American collections.

They cited emails he’d sent to Wiener as evidence that he’d been dealing in stolen statues long after he should have known it was improper. In 2006 he’d sent the New York dealer a photo of a bronze head, explaining that it “was recently found” in northeastern Cambodia. “They are looking for the body, no luck so far, all they have found last week were two land mines!!” he wrote. “What price would you be interested in buying it at?” In another message, he could barely contain his excitement about a statue of Buddha, dug up so recently it was still covered in dirt: “Hold on to your hat, just been offered this 56cm Angkor Borei Buddha, just excavated, which looks fantastic. It’s still across the border, but WOW.”

To disguise the origins of such objects, prosecutors claimed, Latchford would create fake provenance records or invoices. On one occasion he’d instructed a collector in Singapore to prepare false documentation for a piece he was shipping there, “mentioning it has been in your collection for the past 12 years.” The piece was then sent to Wiener with a doctored invoice and letter of provenance, obscuring the connection to Latchford. To facilitate other sales, prosecutors said, he’d provided letters of provenance supposedly supplied to him by a collector who might claim to have purchased a piece in Vietnam or Hong Kong in the 1960s, whether or not that was true. Latchford kept doing this even after the ostensible collector, identified by heritage activists as a Hong Kong businessman named Ian Donaldson, died in 2001.

Although the US government explored options for extraditing Latchford to New York to face the charges, he was much too ill to stand trial. He remained under 24-hour care before dying, from organ failure, in August 2020.

After Latchford’s death, his daughter, Julia, moved quickly to conclude an agreement with the Cambodian government to repatriate the hundreds of Khmer artifacts owned by the family. According to Charles Webb, a British consultant who advised on the deal, she’d concluded that her father had misled her about the nature of his business, and she viewed a complete return of the objects as the only way to be free of the controversy surrounding him. (Julia declined to comment for this story.)

Gordon was pleased with the accord, but he was just as interested in something else Julia agreed to provide: access to Latchford’s records of transactions involving dealers, collectors, and cultural institutions all over the world, among them the Met and the British Museum. Still, to get those statues back, Cambodia would need evidence that would be harder for their current owners to ignore, such as eyewitness testimony of recent looting and archaeological remnants corroborating those accounts. Tracking down and reclaiming all the works would be a huge endeavor, but Gordon, who was working pro bono for the Cambodian government, had become obsessed with getting it done. Collectively, “it’s a massive crime,” he said, “probably the largest art theft in history.”

Toek Tik was still Gordon’s best source. Together they went through Adoration and Glory and Latchford’s other books page by page, and Toek Tik drew maps of precise locations where he said he’d taken statues. He accompanied Gordon and Cambodian researchers the lawyer had hired to more than 20 temples, going over what he remembered. In return, Gordon helped Toek Tik out when he could, for example by covering medical costs. Despite those favors, Gordon didn’t think Toek Tik was revealing what he knew for material gain. “He was absolutely in love with the idea that we were bringing back these statues,” Gordon recalled. “He felt guilty.”

In late 2020 a group of Cambodian government archaeologists began a project at Prasat Krachap that would test Toek Tik’s recollections. After he showed them the spot in the temple’s central shrine where he remembered taking The Peacock and Skanda and Shiva, the team began excavating, removing and cataloging every fragment they found. Among them were a stone arm and ear matching pieces of the childlike Skanda that had been replaced after it was dug up. The archaeologists also found a large base that appeared to have been for The Peacock. Soon afterward, US prosecutors would cite the excavation and Toek Tik’s testimony in a forfeiture filing, calling for the confiscation of the piece.

Toek Tik’s information was evidently reliable, and Gordon started spending much of his time with the former looter. A few months later, Toek Tik began complaining of back pain, which was making it hard for him to sit for extended conversations or make long drives to remote temples. Gordon arranged for him to see a doctor, who delivered shocking news: Toek Tik had advanced pancreatic cancer. Gordon asked specialists in Singapore to evaluate the case, but they told him there was no point taking Toek Tik out of the country for treatment. All anyone could do was try to ease his pain.

“From there, it sped up,” Gordon told me. Toek Tik wanted to finish sharing what he knew, and “we stopped doing everything else and just spent every day interviewing him.” Sometimes, Toek Tik could manage to talk for a whole morning; on other days, just an hour, lying on the floor because it hurt too much to sit. Instead of taking him to temples, Gordon projected Google Maps images onto the wall, trying to jog his memory about each site. They kept going until last November, when Toek Tik contracted Covid-19. He died soon after. “We just didn’t have enough time,” Gordon said.

Even so, there’s now a gradual flow of artifacts returning to Cambodia, thanks in part to Toek Tik’s testimony. In a deal announced early this year, Clark, the Netscape co-founder, agreed to relinquish the $35 million worth of statues he’d bought from Latchford, after DHS agents showed him evidence that they were looted. A different collector, who has remained anonymous, agreed to give up The Peacock, which is now awaiting shipment to Phnom Penh, and the Latchford family has returned Skanda and Shiva. Cambodia is also asking a long list of cultural institutions to prove that their Khmer objects were acquired legitimately. The statues might be distant from the day-to-day concerns of most Cambodians, but they retain considerable spiritual significance, even in a country now dominated by Buddhism rather than the Hindu creeds that were common under the Khmer Empire. “For us it’s the heritage of a thousand years of ancestors. We see that material and also a spirit,” said Phoeurng Sackona, the culture minister. “Many collectors love the statues, but it’s physical, not spiritual.”

Gordon is still traveling the country looking for former looters, who the Cambodian government has pledged not to prosecute if they share information. Almost all of the interviewers he works with are women; they tend to have an easier rapport with the looters, many of whom are old enough to be their grandfathers. Gordon’s team has built a database of more than 2,000 likely looted objects, a significant proportion of them with connections to Latchford—so many that, from Gordon’s perspective, they’re just getting started. “Some days I feel like I understand his network and others not at all,” he said.

In early March, I traveled to Koh Ker with Gordon and his team, hoping to see their work firsthand. At Prasat Krachap, a crew of archaeologists in hard hats and matching blue polo shirts were partway through a fresh excavation, looking for statue fragments. They’d dug down several feet, forming a neat trench around the temple’s central chamber. Some of the artifacts found there were laid out beneath a metal canopy: octagonal stone columns decorated with intricate patterns, plus an elaborately carved roof pediment, depicting a figure that resembled Skanda atop a peacock—similar to the statue that had been taken from just a few feet away. The head of the excavation team, Pheng Sam Oeun, said he hoped eventually to repair some of the damage caused by temple robberies. “When the looters dig, they weaken the foundation, and water can get in and cause erosion,” he explained. “We need to excavate, strengthen the structure.”

Outside a hulking, zigguratlike edifice nearby, Gordon showed me the product of another of his team’s recent efforts. In Toek Tik’s interviews, he’d described the theft of three statues from the complex: two female figures and one male, standing in a row. Gordon sent Toek Tik’s sketch to an archaeologist, who thought one of the females resembled a piece on display in the Met: a “standing female deity” donated in 2003 by Nancy Wiener’s mother, Doris.

The Cambodian government approved an excavation, which was conducted in October 2021. Archaeologists dug in the center of a towering square chamber built from rough-hewn blocks of laterite, an iron-rich material common in tropical climates. At its base, they exposed a rectangular stone pedestal and saw something unmistakable at its center: a sculpted foot, hacked off cleanly at the ankle. The archaeologists removed the foot and the stone blocks around it, which were now sitting in the sun a short distance away. After comparing it to the Met piece, Gordon and his colleagues were confident they matched. “Isn’t that crazy?” he asked, chuckling. Cambodia has asked the Met for detailed provenance records for all its Khmer objects; a spokesperson for the museum said that it’s sharing information and “looking forward to constructive dialogue” with the country.

Before he died, Toek Tik introduced Gordon to many of the looters he worked alongside. We met with one of them on a hotel terrace, not far from the entrance to the Koh Ker complex. Gordon was reluctant to reveal his name; as a precaution, he refers to living looters with code names. This man, in late middle age with thinning hair and a sun-worn face, was Blue Tiger. Through a translator, Blue Tiger explained that he’d begun stealing statues in 1993. He knew the area’s temples well. Decades earlier, his grandfather had worked with a group of Frenchmen who were hunting for artifacts.

Blue Tiger worked as a full-time looter under Toek Tik for about four years, including in the autumn 1997 operation that unearthed The Peacock and Skanda and Shiva. He and his colleagues ranged around the countryside, usually in groups of up to 12 people. Once, two crews of looters apparently strayed onto each other’s turf and began shooting with the Kalashnikov rifles they carried for protection. Toek Tik heard about the battle and told them by walkie-talkie to stop: Both teams were part of the same operation, it turned out.

Sometimes, instead of removing an object right away, Blue Tiger’s team would take a photograph, which was then passed up the chain of brokers and buyers connecting looters in the field to foreign markets. If word came back that someone wanted the piece, Blue Tiger would go back and dig it out. “I knew from my team that all the objects went to Thailand,” he said. “Sia Ford was the No. 1 buyer.” At the time, he never felt as though he was doing something wrong. “But now I feel so sorry. Now I know that these things belong to Cambodia. They were made by our ancestors.”

I asked him if he remembered the largest work he’d taken. It was a stone figure from a temple not far away, he replied. Standing as much as two meters high, the statue was a male with a third eye, a trait of Shiva, and four arms, like Vishnu. Blue Tiger seemed to be describing a harihara, a hybrid deity sometimes depicted in Khmer sculpture. Gordon sat bolt upright. “That would be new,” he said, grinning. Someone passed Blue Tiger a notebook and a ballpoint, and he began sketching.

The next step would be for Gordon to ask archaeologists about the plausibility of Blue Tiger’s recollection. Then they’d have to zero in on the location and hope to find a pedestal or some other remnant. There were no guarantees it would help recover anything, but it was a lead.

“Everyone thought the stones wouldn’t speak,” Gordon told me as we left the hotel a short time later. “But now the stones are talking.”