There are few artists whose output has been as monumentally influential on our collective visual consciousness as Petra Collins, whose photography set the stylistic tone for much of the 2010s. In this FRONTPAGE interview, we sit down with Collins to assess the enormous impact of her aesthetic.

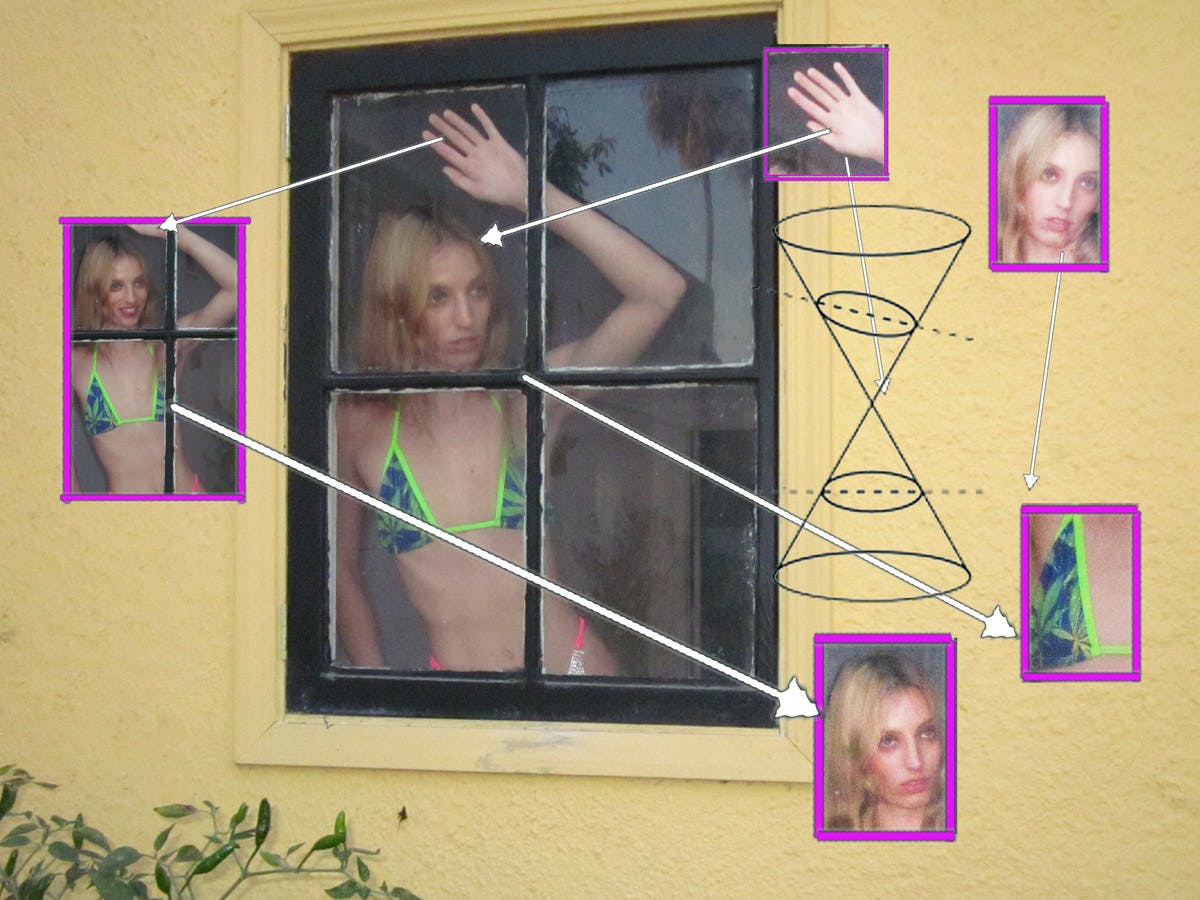

If you are between the ages of 20 and 35, there is a good chance you will look back on the current moment, decades from now, and nostalgically see something like a Petra Collins photograph in your mind. The style she has become famous for — intimate portraits of sweet young faces under a sparkly scrim of soft pastel lighting — has itself become famous, the defining aesthetic of the social media era, blossoming into the standard look for everything from pinkwashed corporate advertising to glittering Instagram and Snapchat filters. Every time you are sold underwear, mattresses, athletic clothes, skincare, or kombucha with a glowing prism of attractive-yet-relatable models in casual repose, you have, in part, the resounding popularity of Collins’ gauzy portraits of Kim Kardashian and Barbie Ferreira to thank.

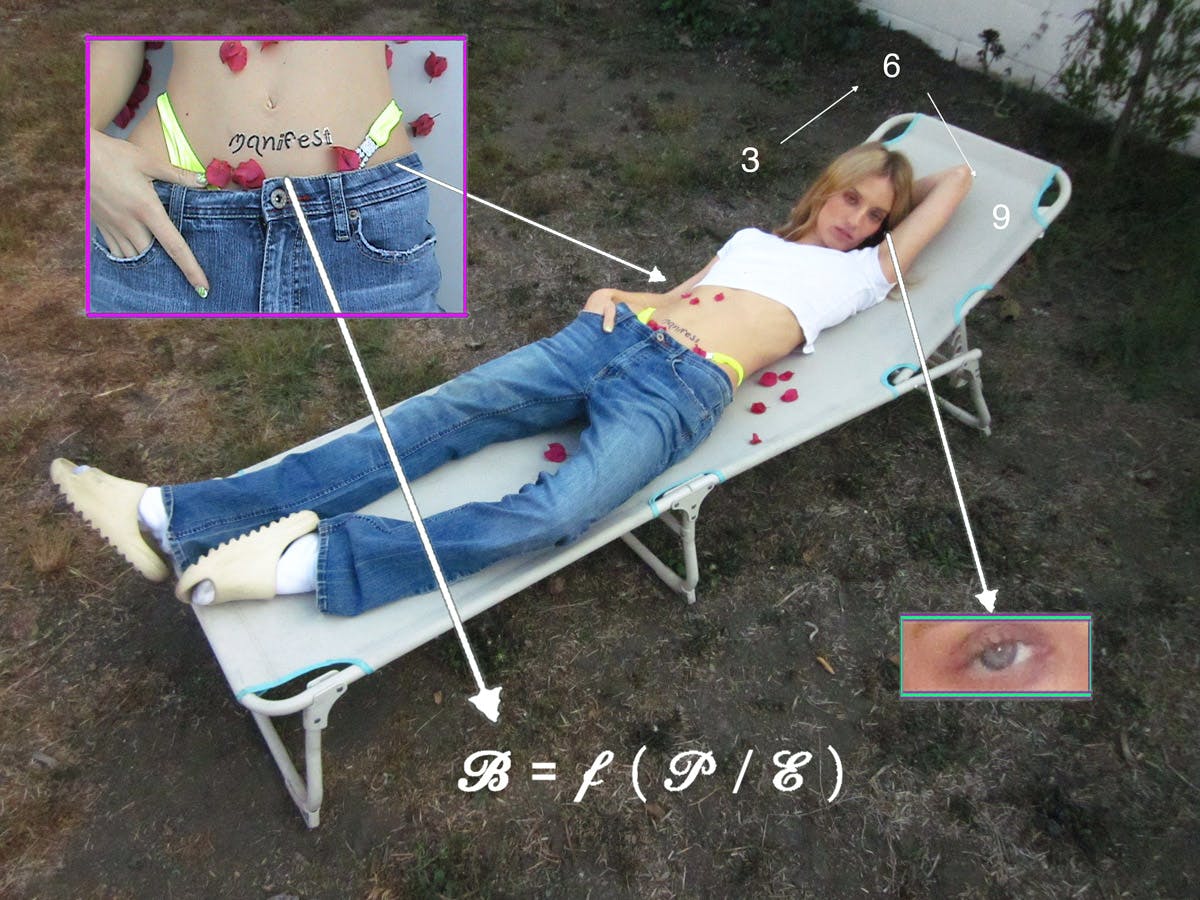

What has become a movement started humbly. Collins grew up in Toronto and began by photographing friends and family, in particular showcasing a raw but relaxed look at teenage femininity. She dropped out of school, moved to New York at 20 with just two suitcases, and grew a bigger audience as the resident photographer at Rookie, Tavi Gevinson’s online zine aimed at young girls. Though her work of the time usually featured her signature halo of rosy and gentle light, there was always something inherently subversive about its aura, too; an empathetic window into the private world of very young women — a world not always taken seriously or treated with generosity by adult society — captured on film by a young woman herself.

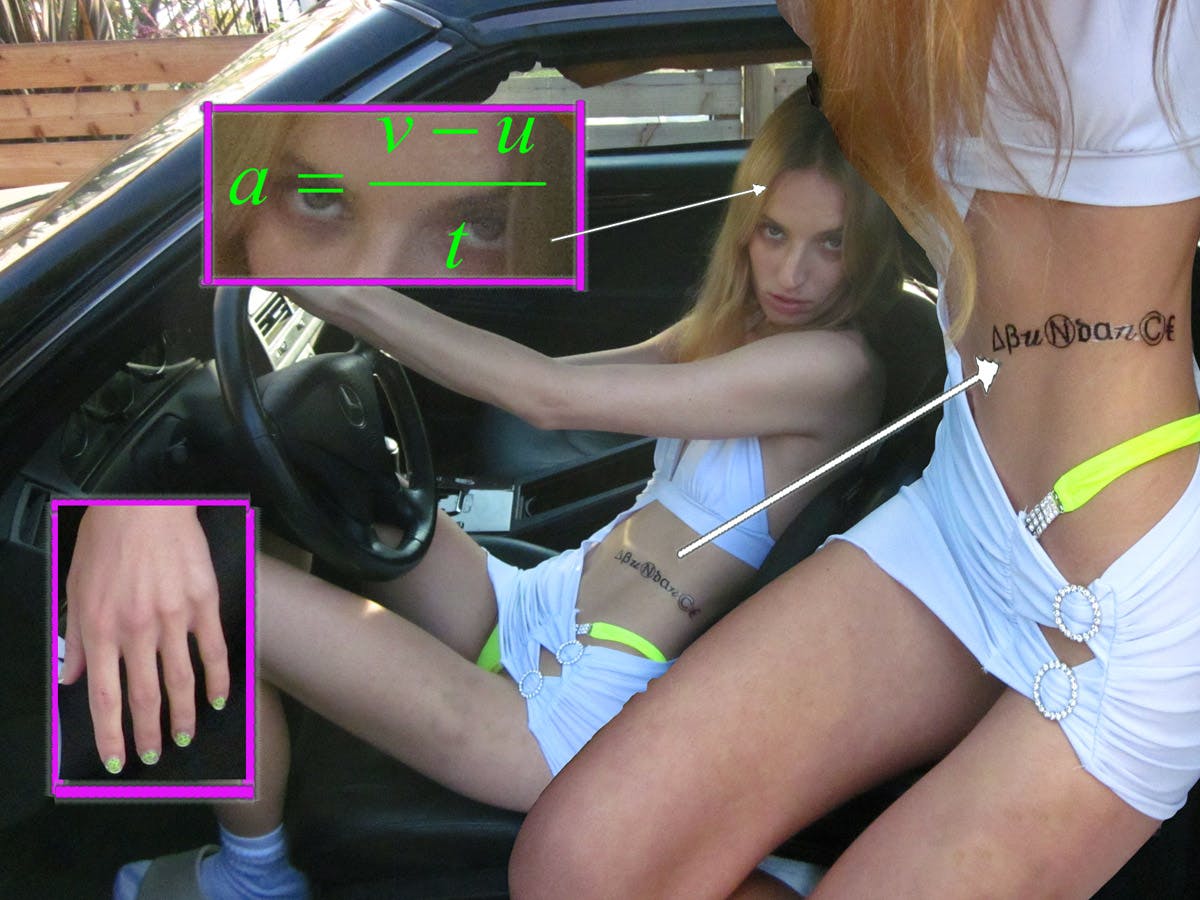

In fact, it was controversy that made her a figure known outside of just art and culture. In 2013, she collaborated with American Apparel on a T-shirt with an illustration of a menstruating vagina on its chest, sparking copious news stories in both praise and condemnation. That same year, she was swiftly kicked off Instagram for posting a photo of her bikini area beneath a twinkling pea green filter, and turned the moment of social media censorship into a righteous rallying cry. These firestorms, besides making her famous, crystallized the context for all of her work, being that any upfront portrayal of a girl’s sexuality will inevitably polarize people in prudish America. From there, she became a sought-after fashion photographer and portraitist, shooting celebrities like Zendaya, Selena Gomez, and Cardi B for magazine covers and being credited with asserting a “female gaze” in an industry still too dominated by men.

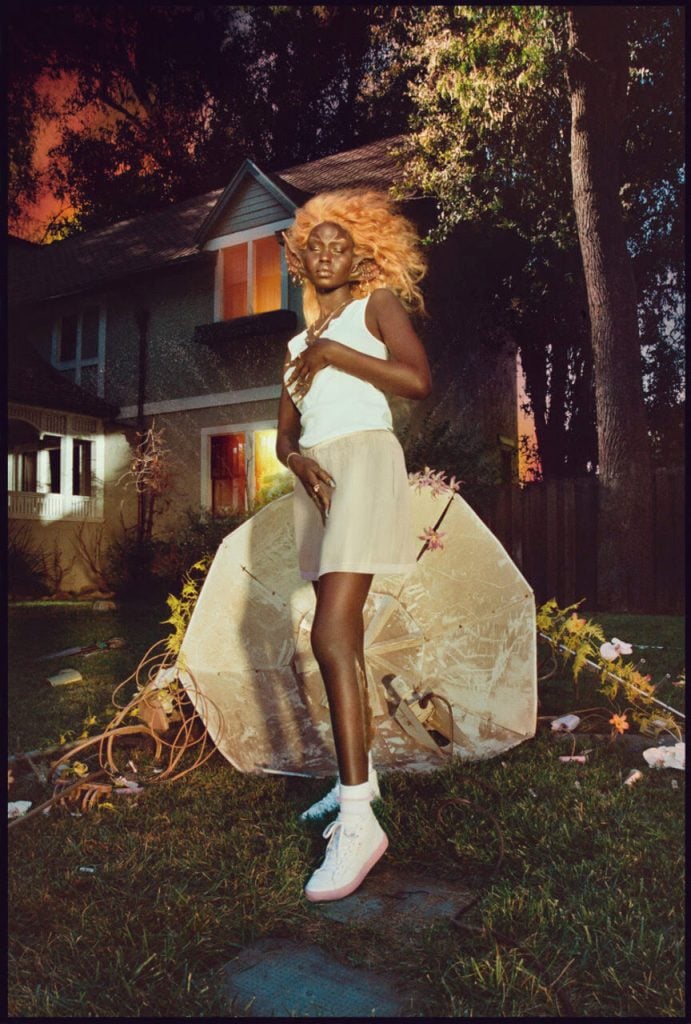

These days, Collins herself has moved on from some of what made her a star — literally and figuratively. She’s gone west to L.A. from New York, is embarking on directing her first feature film (details are being kept quiet), and has even strayed from the golden path of angelic lighting in her work. There has often been a hint of the magical and surreal in her photos, but now we see more of the paranormal and sinister: Models are adorned with lizard scales and tied up like hostages or take kissy-faced selfies on a bed of fake flowers inside of a coffin, the latter perhaps a metaphor for the artist’s attempt to kill and bury her old artistic incarnation. Most tellingly, the prototypical Collins setting — a girlish bedroom — has been set aflame.

Here, the photographer of a generation talks to us about what inspired this turn towards the darker side, the horror and joy that is social media, and staying loose, curious, and open to new ideas after the trends you forged are now cemented into history.

Where are you quarantining?

I'm in LA. I was living in New York and then I've been... secretly living here, because I've been working on stuff here. During quarantine, I just had to get rid of my apartment in New York, and now I'm fully LA.

Do you like it?

I do really like it. I feel I was very... not anti, but I feel people are very judgy about LA. Or anyone from New York who moves to LA, it's like, "Oh, you gave up." I actually love LA, because it's so dark to me. It's crazy because it's a town built on fame. So it has this dark cloud.

What about fame interests you at the moment?

Oh, it fully doesn't interest me — and also really freaks me out. It's the darkest thing for humans. It's very devilish and I don't think it's normal. In LA specifically, it's a really scary thing that everyone strives for. I know people who are insanely famous and it's the worst life.

In what way?

You're just an object.

And kind of lonely, I would think.

So lonely. You're fully isolated.

Sometimes, as a culture writer, I worry about being complicit in the whole celebrity machine — does it ever make you uncomfortable?

I have such a crazy relationship to it. When I came into all of it, I was very young and kind of naïve. I was like, "I'm going to make art, and that's what I'm going to do." I was always making art to not kill myself and survive. When I moved to New York, I still had that beautiful, naïve view of it. I was blind to [my work] being, not used against me, but used for capital gain. So it's bizarre seeing it now — that what I created is now the aesthetic for any type of millennial product. When I was creating it, I felt I was doing something important, or something that would change the world. And so now, I'm like, "What the fuck kind of monster did I create?"

In your newer work, you create literal monster characters with scales and tails. It seems like every year you move away from soft pink lighting and get more and more menacing.

One hundred percent. That's how I started. When I first started taking photos, I was 15, and they're all so dark; that's always what I've loved. Horror and all that has been my inspiration. So it's funny that I ever ended up doing things that were pretty, light, and beautiful. I think maybe because I was really craving that. Now I've gone through that cycle, and I guess, as an adult, I've just unleashed more of my child self, where I'm like, You know what? I am going to do this. I am going to make it gross and scary. For one of my books, OMG I’m Being Killed, it's all editorials and campaigns that were nixed. The cover was a campaign for an unnamed big company, and they were looking for something that was showing femininity. But I was like, "Let's just make an alien." A lot of things get cut — they're like, "What the fuck did you do?"

Do you see the world more and more as grotesque?

It's always been grotesque to me. But I think there was a period where I needed some sort of solace or therapy around it, where I needed to maybe create nicer things, beautiful things for myself — some safety and beauty.

Even though they were shot before quarantine, I found some of the recent images of young women in bedrooms that are lit on fire to be an odd mirror. They show what I’ve come to think of my apartment these past confined months, as my own comfortable space that’s also maybe a bit horrific.

Yeah. I love a personal hell. It's my favorite thing. I mean, my phone is my personal hell.

Are you addicted to your phone?

Fully. 100 percent.

Do you try to break the addiction?

No. I don't care. I like it too much. It's my drug. And, I guess, going deeper and deeper into it does give me, sadly, more inspiration. I can sit on TikTok for eight hours, not exaggerating at all. I've gotten into bed and been like, "I'm going to look at three [TikToks]," and then it's 3:00 a.m.

By chance, have you ever played 'Animal Crossing?'

That was my quarantine life. It's heaven.

It’s wild that you create this avatar who lives on a fantasy island that you name and design, and it essentially exists in real time along with you — if you turn it on at 5 a.m., it’s 5 a.m. in the game, the sun just rising. You fully inhabit virtual reality.

There's many moments, actually, when I cried on it. Animal Crossing is so pure. The purest form, I think, of the Internet and simulation. It's so beautiful. And it is also patient. You can't accelerate time. It's based on the time that you're in.

It’s another part of my reality. That island is real. I lived on that island. I was in those spaces. We can't discount those experiences. There's no way that's not real. That's your own full reality.

How else has quarantine affected you creatively?

It was really good for me to take that sort of pause. I'm moving into directing a film. I spent a year writing it — we have our lead and a lot of the cast — and then quarantine hit, and they were like, "We don't know now."

What can you tell me about the film?

It's a body horror film about the Internet and about validation and all of that. Basically everything that I've experienced or seen. Pre-quarantine, it was almost difficult to explain to everyone what it was about. Now, with everyone having to only live URL, not IRL, people are like, "Oh, okay. We get it."

Since you’re interested in the ways the Internet makes victims of us, I wonder if making art about these anxieties helps you feel more powerful, or in control?

Maybe less powerful than in touch with my body and some form of reality. I was a dancer from a very young age, and I had to stop because I had to get surgery on my knee. Until I was 15, I thought that's what I was going to do, dance, and it was crazy having my body betray me. That's why I love the physical aspect of photography, because it's nice to have a tool that I can create with. I love [shooting with] film. I'm not a film snob at all, it's just that I love the whole process of holding the camera, the film, the light hitting the film. I just need to have that physical whole dance with it, to really experience taking photos.

You’ve talked a lot about how investigating these themes of femininity has been a way for you to think about your relationship with your own body. How is that relationship at the moment?

My relationship with my body is so fraught, and I don't think that Instagram has made it any better. It's funny to see how trends around the body work, or how they change and everyone molds to it. The filters really fuck me up. It’s dark.

And now, with all the plastic surgery, it seems like people are applying a specific kind of Instagram-friendly filter right to their actual physical face.

I don't think it's a conscious thing. We're just removing ourselves from any type of real. Which is why I started creating monsters more — we're very over any form of real. What I find so funny about photography right now is that people are trying to get back to the real. But there is no fucking real. And now, with quarantine, it’s rapidly propelled, because we are all allowed to only live on our phones, to only present through our phones. We never see anyone else. It's the Wild West of fake.

Do you care how your images are interpreted? I’m thinking perhaps of your explorations of sexuality and younger girls — did it ever worry you?

The thing is, I was young when I was creating those. It's not my job to be the gatekeeper of how people interpret it, but it is my job to create imagery that is morally true, or safe to me. So if that's what it is to me, it's fine for me to create those images. I think a lot of what I was shooting back then, I wouldn't necessarily shoot now. People are going to interpret my images however they want.

You said that film and photography can help you feel safe — how?

I grew up with a lot of mental illness in my family, and I also suffer from that. I had a difficult time in school because I had learning disabilities. The turning point for me with photography was when I did this series of my sister's friends in my bedroom. I didn't have a concept of what photography was or how it would feel or what it could do. And I just thought stupidly that what I saw would be exactly what would come out of the camera, which obviously is not how it is. It was pretty bright in my room, and they were having a kind of dark conversation for young women — one of the girls was talking about some shitty sexual experience. And I remember thinking the photos would come out one way, and I got them back and they were so beautifully dark. I realized that my emotion behind the camera and their emotion in front totally informed what the images looked like.

You believe that the emotions and spirit of the room affects the finished photo?

Yes. Fully. It made me realize how close I could get to what was in my brain, or what was in anyone else's brain. I was also, at that age, not living a teen life. I had a really difficult home, and I left really early. I was also in a very abusive relationship at a young age with someone a lot older. I was trying to create imagery of a reality that I wished I lived in, which was this teen world that was a little dark, but it was still teen. I wanted to be a teenager so badly. What I was capturing, I guess, was half of my angst and then half of this nostalgia for something that never happened. Not the past, just nostalgia for this teenhood that I wish I was able to experience.

How do you keep changing, moving, evolving, and not just fall into a rut of doing the same thing over and over?

Because I won't be happy. My happiness comes from creating work, and it's really tied with my mental health. I constantly need to get these ideas or things out of my body, or I don't know what will happen. So whether they work or they don't work, I have to do them. That's the difference between real artists and not — do you need to do it, or do you not?

A lot of people get stuck. They're like, Okay, I found my thing and I'm not going to either critique it or discover anything else. But I've always felt like an outsider. I don't fully subscribe to anything. There's obviously that part when people are like, Okay, this is cool. Now we accept you. But then I’m already doing something else. And I don’t care.