Miles Aldridge

Fashion Photography

as Social Commentary

When Vogue Italia published a spread by Steven Meisel that was inspired by the deadly Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010, it provoked criticism. Bloggers and fashion critics called it tasteless and exploitative, given the devastation to the Gulf of Mexico’s ecosystem. This was neither the first, nor the last time that the publication sparked controversy, and it reinvigorated the debate over what is and isn’t acceptable in fashion photography.

That discussion will continue at the second Photo Vogue Festival, where an exhibition titled “Fashion & Politics” brings together some of the magazine’s most tendentious shoots. “Fashion is not as frivolous as a lot of people might think,” said Alessia Glaviano, the magazine’s senior photo editor, who co-curated the show with her colleague Chiara Bardelli Nonino. “And, as an industry, we’re partly responsible for this perception because we rarely engage in a critical discussion of our work.”

While she welcomes criticism, she notes that because she sees fashion as political, fashion photography can and should offer social commentary. One needs only to attend protests and rallies to see how clothes helped people proclaim their ideals. The “pussy hat” became the symbol of the Women’s March while Trump supporters sported red caps reading “Make America Great Again.” Shirts declaring “The Future Is Female,” “Nevertheless, She Persisted” and “Nasty Woman” face off with those still demanding “Hillary for Prison ’16.”

“The way we dress is intrinsically tied to identity and culture,” Ms. Glaviano said. “We put on clothes every day to communicate something about ourselves.”

Caring about one’s looks when participating in acts of civil disobedience is not new. During the civil rights era, nonviolent protesters were told to wear their Sunday clothes to create jarring contrasts, while the Black Panther Party asserted its presence through a uniform that underscored the group’s revolutionary discipline. And the outrage Beyoncé encountered when she performed at the 2013 Super Bowl in an outfit inspired by the Panthers is a testament to an ensemble’s provocative power.

Thinking about the ties between clothing, photography and politics, Ms. Glaviano recalls Jonathan Bachman’s photo of Ieshia Evanscalmly facing the police during a Black Lives Matter protest in Baton Rouge, La. “Part of its power comes from the contrast between the way she appears, graceful in a long summery dress, and the hefty gear of the riot police,” Ms. Glaviano said. “It could be a fashion spread.” Yet, when Pepsi alluded to that moment in an ad starring Kendall Jenner, the public outcry was so intense that the company was forced to pull the commercial.

“When a business co-opts a political movement, that’s when it becomes blurry and messy,” Ms. Glaviano said. She believes the images featured in Vogue Italia belong to another category: more art than advertising. “We need to question this notion that because we’re in the business of promoting garments, we can’t comment on what is happening in our societies,” she said. “True, while the magazine is on stands, you can find the designs in stores, but three months later, that’s no longer the case: The clothes go, the photographs stay. The photographers we work with are artists. As such, they have a point of view, a perspective and a vision to share. They use clothes merely as a tool to tell stories, much like a movie uses costumes.”

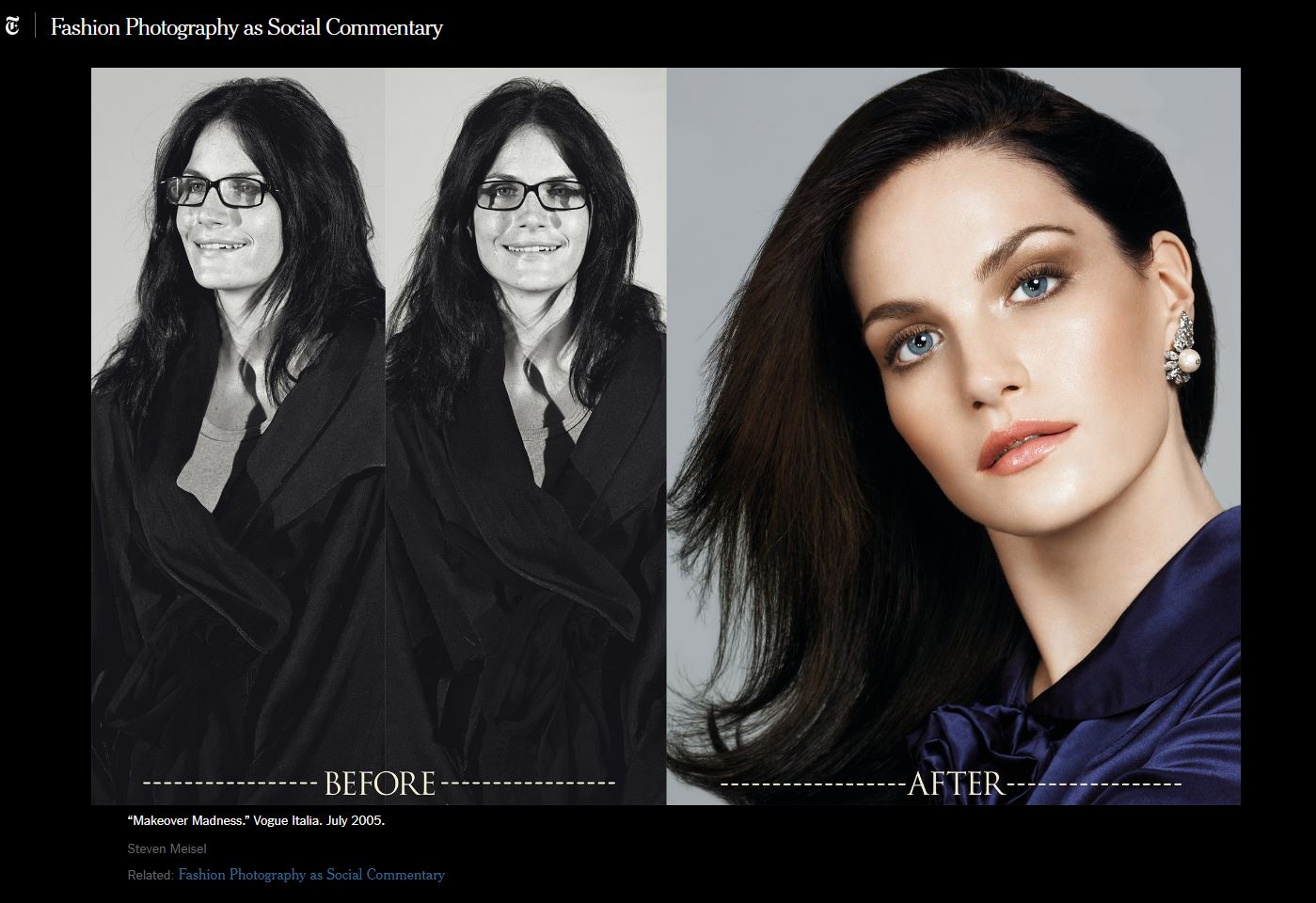

Steven Meisel is a prime example. Besides the aforementioned “Water & Oil” spread, he’s produced several politically charged works for the Italian glossy. “State of Emergency” shows women being roughed up by riot police and airport security agents. “Make Love Not War” depicts soldiers and models in eroticized scenes. These were met with accusations of glorifying war and glamorizing violence against women for the benefit of selling high-end clothes. “Yes, there’s a lot of brutality in those spreads, but aren’t we reflecting what’s happening in society?” Ms. Glaviano said. “We’re denouncing it, not endorsing it. Unfortunately, too often people have already made up their mind about what fashion photography is, and they’re not willing to see the nuances.”

She believes that if you trace the evolution of fashion photography, you would notice how it merely mirrors shifting societal norms. “A picture doesn’t change things,” she said. “It simply arrives at a moment where society is ready to make some changes and becomes a catalyst.” For instance, she notes how models in the 1950s were portrayed as cold mannequins, an indication of how women were considered passive; how spreads in the 1980s stressed glamour, reflecting society’s obsession with wealth; how nowadays, through social media and the rise of the female gaze − last year’s theme − the industry had to think of beauty as much more inclusive; and how a photographer like Peter Lindbergh has been exploring ideas of masculinity, femininity and androgyny as communities have slowly been embracing a broader understanding of gender identity.

But not all fashion photography is or should be political. Sometimes it is undeniably commercial or unambiguously about celebrating beauty. The centerpiece of this year’s festival, on display at the Palazzo Reale, is Paolo Roversi, whose work stands as a counterpart to the likes of Meisel. Going through an archive of 150,000 images, Ms. Glaviano appreciated how his work is pure poetry based on a feeling for light and reflection on the medium itself.

“A successful magazine is one with a diversity of approach in its pages,” Ms. Glaviano said. “It can’t always be political, nor can it just be fantasy. Rather, it ought to be as multifaceted as the society it exists in.”