Opinion

A Month After I Published a Book About How to Run an Art Gallery, I Closed Mine. Here’s Why

The co-founder of the gallery yours, mine & ours on the current gallery crisis.

In November 2018, the second edition of How to Start and Run a Commercial Art Gallery, a book I co-authored with Edward Winkleman, was released. The following month, my gallery partners and I announced we were closing our own two-and-a-half-year-old space, yours mine & ours. Fun timing, no?

In fact, the sequence of events didn’t feel all that surprising to me. The economics of a small, multi-partner gallery require either independent wealth or a second job, which limits the business’s ability to grow. Compound that with a rapidly slowing emerging art market reflective of structural shifts in the US economy and you can begin to see what we, and others like us, were dealing with.

Before opening yours mine & ours on New York’s Lower East Side, I had worked at two other galleries, Judi Rotenberg gallery in Boston and DODGEgallery in New York, both of which closed. (Look out for my forthcoming memoir, How to Close a Commercial Art Gallery.)

When my partners and I sat down to develop the model for yours mine & ours, we sought to push against industry norms that seemed to hamstring small businesses (a big space, participation in too many fairs, a large stable of artists, splashy print ads).

Installation view of Rachel Hecker, “Exhibition Title Goes Here” September 2017. Courtesy of yours mine & ours.

Content to remain small so we could control our overhead, we wanted to show many artists but represent few, often giving representation only when the artist asked for it. At a moment when galleries all around us were closing, we felt it was more important to offer opportunities for artists we believed in to show their work. Many of them moved on to work with other larger galleries, a fact we’re proud of and embrace.

What It Really Takes

Just a few years ago, the art industry was deeply concerned about the closure of midsize galleries. It used to be that if you were big, you were dominant and safe, and if you were small, you were nimble and safe. As the bifurcation in the broader economy has grown, however, that’s changed—and the shifting economics are having a big impact on the way galleries operate.

In our book, Ed and I note that you either need to have a large amount of seed funding or a second job in order to support yourself during the early days of your gallery. By the time we opened yours, mine & ours in 2016, I knew that I would need to keep my full-time job, first as director of partnerships at Artspace and then as director of arts at Kickstarter, so as not to rely solely on income from the business. Similarly, my co-founder Nick Rymer would continue to teach and, in turn, our third partner RJ Supa would be the main presence in the space. As many know, you don’t have to be physically in the gallery to work on its behalf.

Patton Hindle. Photo: Sean Fader.

What I loved about my life during that period was the way my work at the gallery and at Kickstarter fed into each other—I rarely had a professional conversation limited to just one. Both positions sought to build communities and help artists, and both felt like forms of patronage.

Ultimately, however, as my role at Kickstarter grew, it became personally unhealthy to continue in both roles. My responsibilities as a gallerist—organizing exhibitions, writing press releases, doing studio visits—often conflicted with travel for my day job. At one point, I took a vacation day from Kickstarter to help paint the walls at the gallery from black to white.

Over Thanksgiving, I told Nick and RJ that I had to choose the position that could support me. We had always agreed to run the space together, so I knew my decision might affect their choice to carry on. Also weighing on us was the slowing art market and constant financial pressure. Our rent, cheap for New York, came out to $3,000 per month, including real estate taxes. But we took many risks in our programming, often showing work that wasn’t sellable or by artists right out of school, priced under $1,000.

Installation view of Todd Bienvenu, “Water Sports” April 2017. Courtesy of yours, mine & ours.

I can’t say we made one significant financial mistake, because we didn’t. But collectors were primarily interested in the more expensive work we showed ($15,000 and up), while we weren’t willing to stop offering opportunities to young, untested artists.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the past year reading article upon article trying to identify what the “problem” might be—art fairs, the internet, you name it. I don’t think any of those factors individually are the culprit. The problem is much deeper, and much broader.

Economics Lesson

The art market is known to move in cycles, and it seems fair to say that we are currently experiencing a downturn in the middle and lower-priced art market. But another phenomenon threatens to make this downturn permanent: a diminishing pool of young, engaged, dedicated collectors.

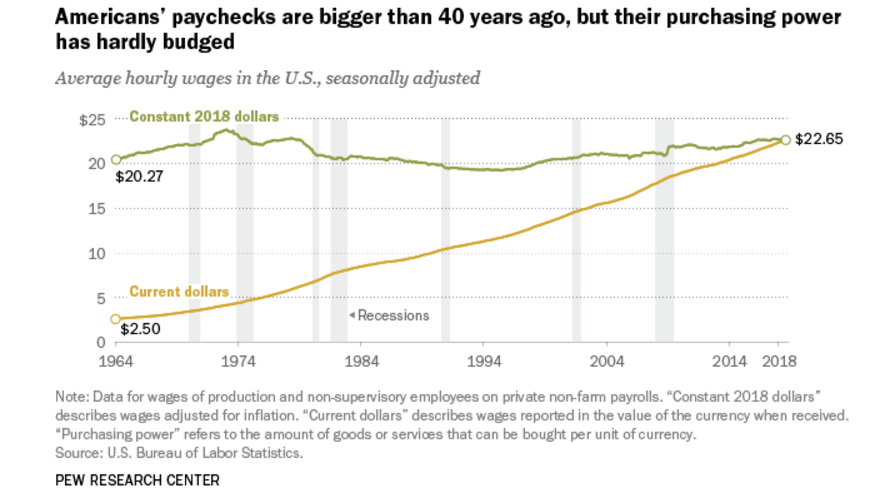

Part of the reason for the shrinking young collector base is economic: Fewer young people are turning to collecting because of wage stagnation and the rising cost of living, especially in major metropolises.

Courtesy of the PEW Research Center.

As the PEW Research Center reported in August, today’s average hourly wage is essentially equivalent to that in 1978 due to an incredible spike in the cost of food, rent, healthcare, and other necessities. Most people simply have less disposable income than their parents or grandparents did. At the same time, more employers are relying on freelance workers, which means many denizens of the “gig economy” have to work more than they might have in the past for the same quality of life.

Would it even be possible for the exceptional, inspiring collector couple Herbert and Dorothy Vogel to build their collection of more than 4,000 works today? In the ‘60s, the pair used their disposable income—a public librarian’s salary and a postal service worker’s salary that topped out at $23,000 per year—to buy art that they loved. But $23,000 in 1975 would amount to roughly $110,000 today. That sounds healthy, but doesn’t go very far when you add in the cost of living in a major city like New York.

Millennials, in particular, have a different relationship to spending than our predecessors because we were indelibly shaped by the recession. (I say this as a 33-year-old who graduated from college in 2008, deemed the worst year to enter the workforce since the Great Depression.) As Michael Hobbes wrote in The Highline, recessions have lingering effects on young people:

In 2007, more than 50 percent of college graduates had a job offer lined up. For the class of 2009, fewer than 20 percent of them did. According to a 2010 study, every 1 percent uptick in the unemployment rate the year you graduate college means a 6 to 8 percent drop in your starting salary—a disadvantage that can linger for decades. The same study found that workers who graduated during the 1981 recession were still making less than their counterparts who graduated 10 years later.

A Call for Action

So what does all this mean for the future of the art world? I frequently hear galleries and arts fundraisers say they struggle to connect with people in their late 20s and early to mid-30s. That makes sense: When the small, self-selecting group that might be predisposed to buy art is put under pressure by real economic factors, a whole generation becomes significantly less likely to collect in a serious way. At the same time, the number of galleries has grown exponentially since the 1970s. The combination suggests that more closures are inevitable, and this makes me sad.

Rochelle Feinstein’s The Week in Hate (2017). Courtesy of the artist, On Stellar Rays, and yours mine & ours.

I’ve spent my career thinking about ways to support artists and the ecosystem that allows them to work. Now, I believe we are at a turning point: Our focus needs to shift outside the insular art world and toward our local politics. We need to research what our representatives stand for and push for the agendas that benefit artists, galleries, and our wage-earning peers, as well as policies that benefit the lower and middle classes more broadly, such as raising the minimum wage, fighting against real estate rezoning, higher education debt forgiveness, and affordable healthcare for all.

At the same time, let’s stop blaming the individual facets of the art system—fairs, the rise of social media, and so on. And let’s be generous to one another and stop judging artists and galleries for trying something new, like raising money on Patreon or Kickstarter, sharing spaces, or using an online sales platform.

Instead, remember the root causes of the problem. We all have the same goal: to create an industry and an economy that can support us, and others, better than the one we have now.

Patton Hindle is the senior director of arts at Kickstarter. She also co-founded the gallery yours, mine, and ours, which closed in 2018.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE