|

Art Market

The Differences between Prints, Multiples, and Editions

In the past few years, the market for prints, editions, and multiples has seen a dramatic uptick. Thanks in part to the popularity of artists who have made these types of replicated works major parts of their practices—like

and

—along with an accompanying surge of younger collectors whose tastes and budgets align with these media, dealers and auction houses have seen a growing appreciation for a category that long played second fiddle to painting and sculpture. Despite this marketplace momentum, one major sticking point remains: What, exactly, is the distinction between prints, editions, and multiples?

and

—along with an accompanying surge of younger collectors whose tastes and budgets align with these media, dealers and auction houses have seen a growing appreciation for a category that long played second fiddle to painting and sculpture. Despite this marketplace momentum, one major sticking point remains: What, exactly, is the distinction between prints, editions, and multiples?

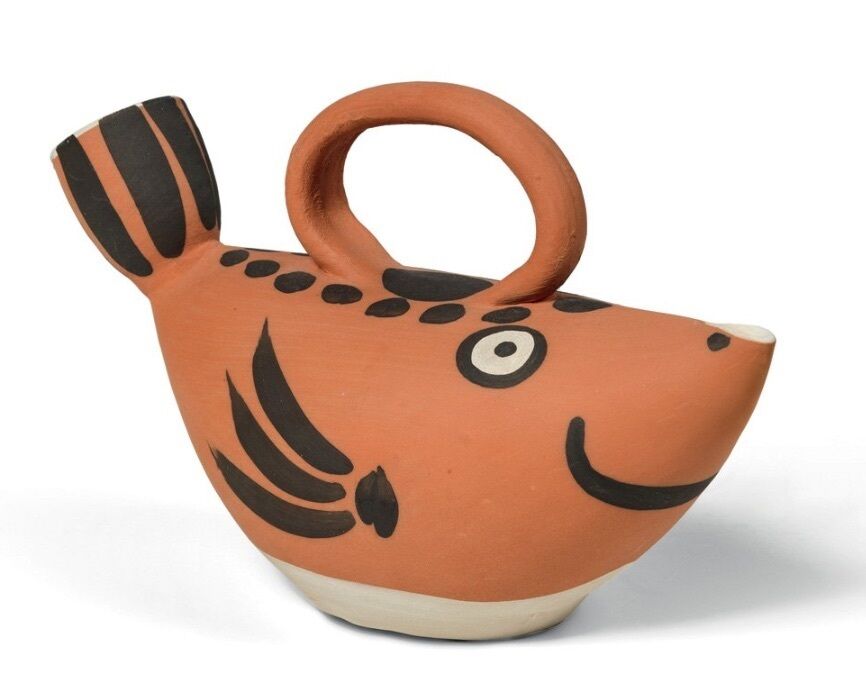

Ostensibly, these categories are fairly straightforward to define. According to Lindsay Griffith, the head of Christie’s department of prints and multiples, “Prints are typically described as work on paper made with a number of examples (called an edition). Editions are often used to describe contemporary works of art made in a series. Finally, multiples are typically three-dimensional works made in edition such as

ceramics or KAWS companions.”

ceramics or KAWS companions.”

From there, however, things get a little complicated. “Importantly and confusingly, you will also find these words in places all used interchangeably!” said Griffith. “It’s relatively rare to have prints referred to as multiples at this point, but it’s not wrong,” said Jeff Bergman, director at Pace Prints. “Editions, as far as I’m concerned, can refer to everything under the sun that’s not a one-off or unique.”

, for example, will often make smaller, editioned versions of large-scale sculptures that are more affordable to the average collector. While his 10-foot-tall Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994–2000) sold for a record-breaking $58.4 million at Christie’s in 2013, 10-inch versions are available as an edition of 2,300 for a relatively modest €8,500 (about $9,500).

Prints are often made with a similar democratic intent. “There’s no rule of thumb for this, but you will find that a print will be something like 10 to 25 percent of the price of a unique work on paper by that same artist,” said Bergman. “In theory, the smaller the edition, the more you can charge.” There are, of course, exceptions to this rule. According to Bergman, artists who have an established printmaking practice and a high market demand, like

, can often command price points for editioned works that are comparable to their unique works on paper.

, can often command price points for editioned works that are comparable to their unique works on paper.

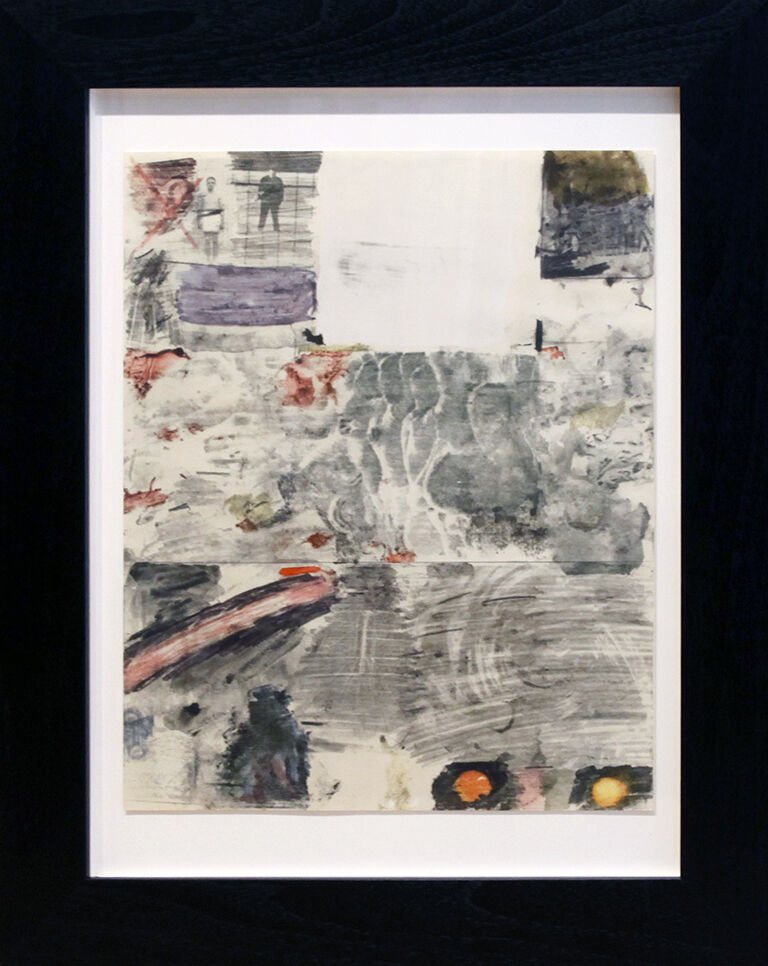

Though it may well seem as though “editions” could simply be used to refer to both multiples and prints, there is an important catch: Not all prints are editioned. “You can create prints that are their own unique works,” said Jeremy Ruiz, studio manager at the Lower East Side Printshop. These prints are often either monotypes or monoprints. Monotypes are essentially created by painting directly onto a plate and pressing a piece of paper on top of it in order to transfer the image. A monoprint, meanwhile, can use any number of techniques, but is still essentially its own, distinct, un-recreatable work.

“Printmaking is the bastard child of the art world and monotype is the bastard child of the printmaking world,” said Ruiz. “How these works are defined is really up to the artist.” Artists like

and

are prime examples of this. Though the two artists both famously used silkscreen techniques to replicate images, they printed onto canvas instead of paper and considered these works paintings, not prints.

and

are prime examples of this. Though the two artists both famously used silkscreen techniques to replicate images, they printed onto canvas instead of paper and considered these works paintings, not prints.

That distinction is an important one. Warhol’s silkscreen-on-canvas works are routinely among the top lots at auction in a given season—his one-of-a-kind 1963 work Eight Elvises, for instance, fetched $100 million in 2008, placing it among the most expensive works of art in the world at the time. Meanwhile, his prints on paper tend to sell for relatively reasonable sums in the six figures, or, in the case of his unlimited editions (also called non-editioned multiples), for a little under $400.

There are also variable editions, which, as the name implies, are editions that are varied slightly piece to piece. That could mean that they are on different surfaces, are made of different materials, are colored differently, or use slightly different techniques. Often, these are signed with the initials “EV” along with the edition number.

Far from being hard-and-fast rules, the distinctions between prints, editions, and multiples serve far better as loose guidelines that help clarify the work’s value and give artists a kind of agency over their market. For artists in high demand, editions and multiples allow for greater accessibility. And while prints’ overlap with the world of editions and multiples is significant in many ways, their market can sometimes be a universe of its own.

Shannon Lee is Artsy’s Associate Editor.