World’s Oldest Operating Photo Studio Closes in India

“We only had the building on lease and due to a space issue, and a discrepancy on the rent, [LIC] wanted it back,” co-owner Jayant Gandhi told the India-based Writing Through Light. “We filed a case in 2002 and finally lost the battle to the court order.”

Now in his 70s, Gandhi also cited the difficulty of running the business at his age and the impact of digital technology as reasons for the closure. He and co-owner K.J. Ajmer had expanded operations to include work on commercial shoots and processing services for 16 and 35mm motion-picture film, but reaping strong profits still proved challenging. Gandhi told The Hindu that he now intends to try and preserve the studio’s archives and equipment, although he has not shared any specific plans. A petition asking LIC to convert the space into a museum has emerged on Change.org, but it has so far amassed fewer than a dozen signatures. Listed by the Kolkata Municipal Corporation as a Grade IIB Heritage Property for its “architectural style,” the building itself should at least continue to receive protection and proper maintenance from LIC; according to the corporation’s guidelines, only “horizontal and vertical addition and alteration … compatible with the heritage building” are allowed.

LIC, however, has long neglected the structure. It still sports a massive hole in the roof that dates to 1991, when a large fire broke out. The main studio and library, then on the top floor, contained around 2,000 glass negatives — used to reprint images for sale — that were lost to the blaze: Gandhi told Times of India he had stored some of the archive’s most cherished ones in a large iron safe, but the flames damaged the metal and he was never able to open it again. Since the disaster, business has been on the decline.

At its peak, Bourne & Shepherd had numerous outlets not only across India but also in London and Paris. It began in the northern India city of Shimla, where Bourne founded a studio in 1863 with another photographer, William Howard. Initially a bank clerk in Nottingham, Bourne had acquired his first camera just a decade prior, according to photographic historian Hugh Ashley Rayner in his catalogue essay for the exhibition Bourne & Shepherd: Figures in Time (curated by Tasveer gallery, the traveling show just finished its run in India, only days before the studio closed). Bourne first approached photography as a hobby, snapping pictures of the marketplace from his window at work, but after exhibiting some of his images, he decided to move to India to pursue it as a profession.

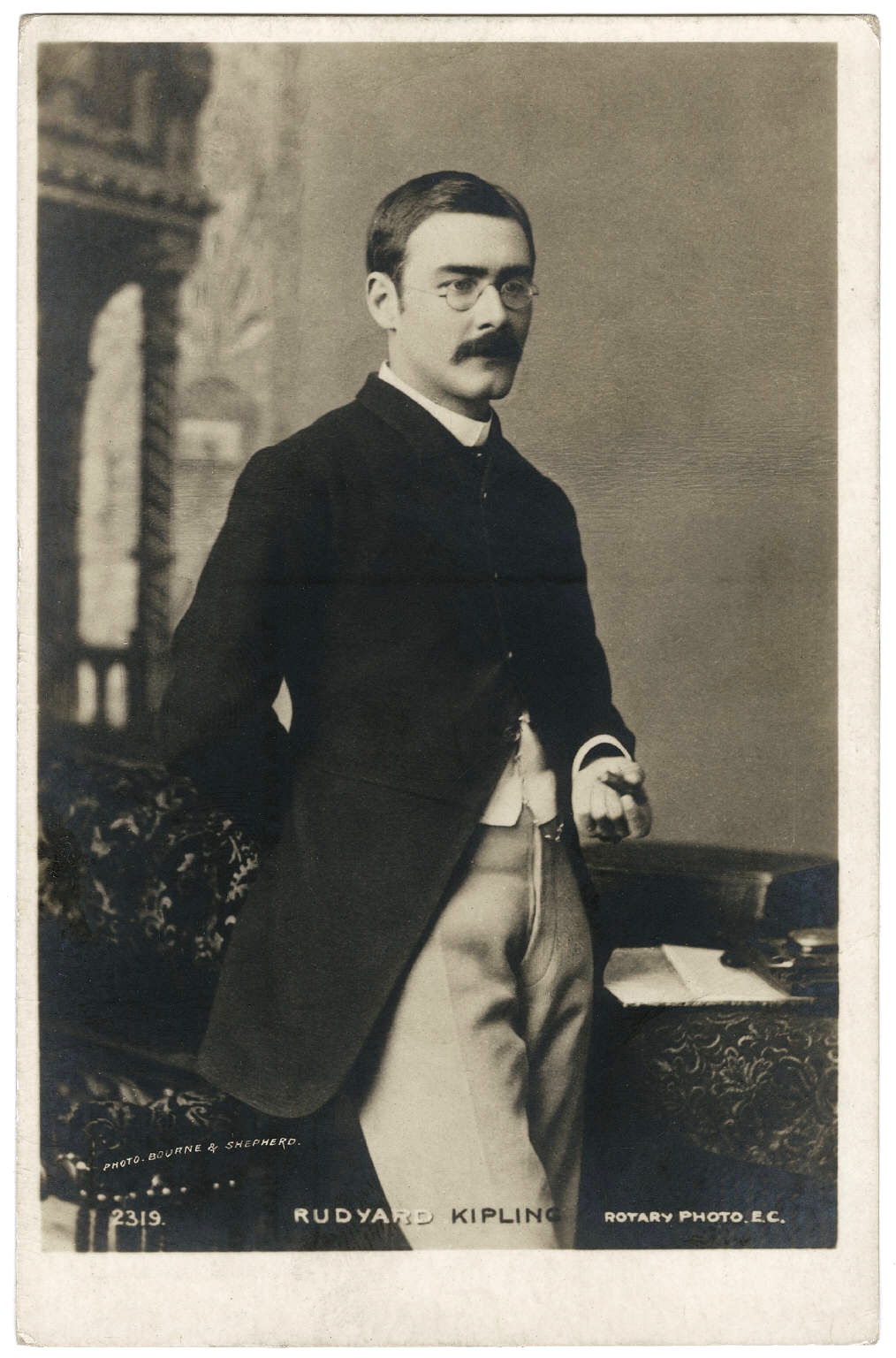

Bourne

& Shepherd’s photographic postcard portrait of Rudyard Kipling (c.

1892) (photo courtesy the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library,

Yale University, via Wikipedia) (click to enlarge)

The company’s first studio in Shimla was known as “Talbot House,” named for photography pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot, Rayner writes on his website. By 1865 it also had a branch in then-Calcutta that moved locations a number of times before settling, in 1910, into its Esplanade premises. Bourne & Shepherd’s other studios closed over the years, but the Kolkata one endured, with the business prospering through the 20th century. Besides making portraits of people from Indian mystic Sri Ramakrishna to English writer Rudyard Kipling, the photographers also documented important events including the Delhi Durbars of 1877, 1903, and 1911.

“The company became the de-facto official photographers to the British Raj in India; and produced portraits of successive Viceroys and Governors, as well as most high officials and major political events,” Rayner writes. “Everyone who was anyone in British India, had their portrait ‘done’ by Bourne & Shepherd, at some point in their career!”

While Shepherd primarily worked as a printer, took portraits in the studio, and managed the commercial side of the business, Bourne traveled extensively, capturing the architecture, scenery, and people of India. He was an expert in the wet-plate collodion process, which required setting up a fully equipped darkroom tent near the capture site to quickly process the plates — and he apparently succeeded even while “perched on a mountainside in the remote Himalayas, with the thermometer approaching a hundred degrees and a dusty gale blowing,” as Rayner describes.

“Although not the first serious photographer to document the landscape and architecture of India, he was perhaps the first to produce such a large and coherent body of work of such consistently high technical quality and artistic merit,” Rayner continues. “His images recorded an India that was rapidly changing, and that has now largely disappeared.” Many of these images now reside in the collections of museums around the world, from London’s National Portrait Gallery to the Smithsonian Institution.

Left:

Bourne & Shepherd, “Jaipur, His Highness, Maharaja Ram Singh,

G.C.S.I.” (1877); right: Bourne & Shepherd, “Udaipur, His Highness,

Maharana Sajjan Singh” (1877) (photos courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

Samuel Bourne, “Agra, The Taj Mahal from the corner of the quadrangle” (1865) (photo courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

Despite this rich history, LIC is not interested in preserving the old Bourne & Shepherd studio, Gandhi told Times of India. He does not intend to sell any of the old photographs or equipment for fear that people may misuse them, but also doesn’t know where to find the space to hold all the artifacts he’s amassed over time.

“I am sad that it is gone,” he told Writing through Light. “But in the end, there are some things that are out of one’s control.”

Bourne

& Shepherd’s c. 1875 photograph of the rifle-toting Prince of

Wales, posing with a tiger he killed and members of his hunting party

during his tour of India (via Library of Congress)

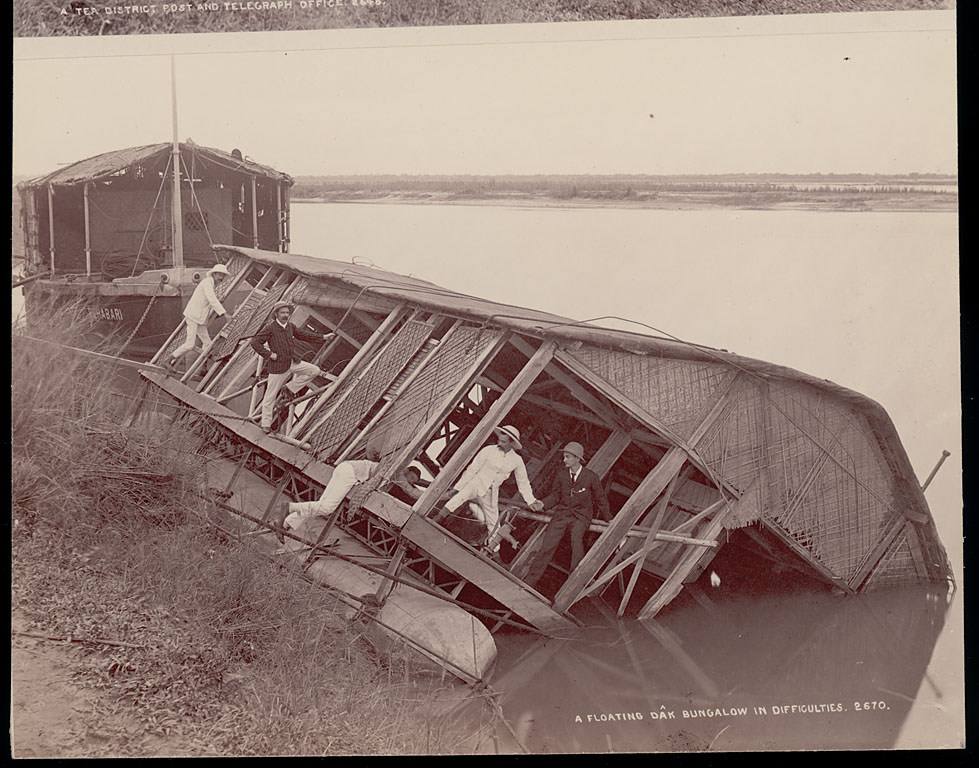

Bourne

& Shepherd, “A Floating Oak Bungalow in Difficulties” (c. 1903)

(via the Emma A. Koch photograph collection of India, South Asia, and

Australia, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

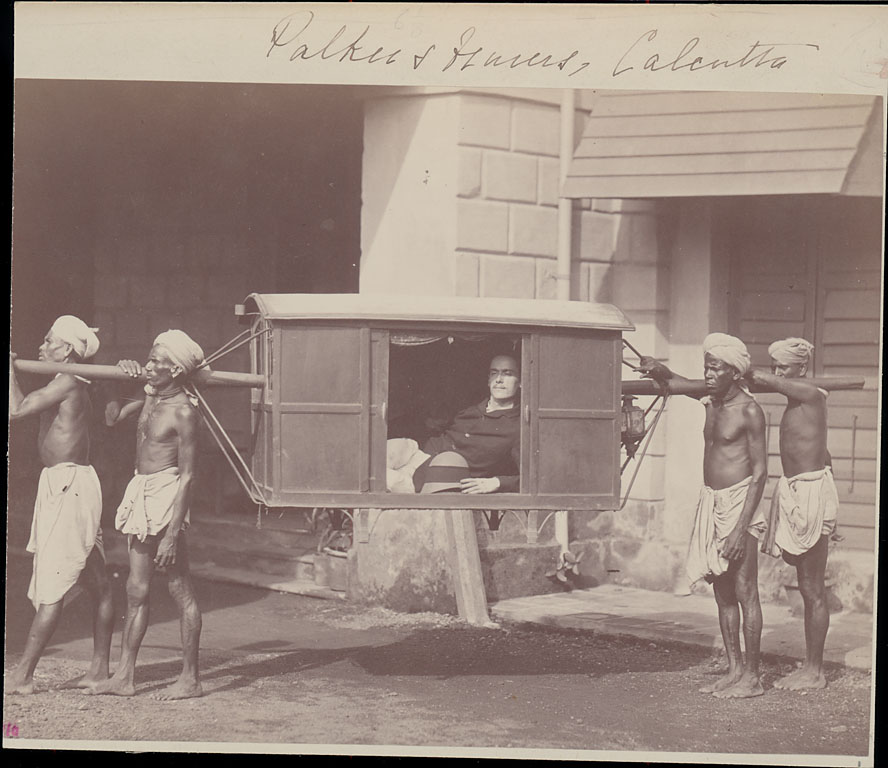

Bourne

& Shepherd’s photo of four Bengal men carrying a man in a palki or

palanquin (c. 1862–85) (via Emma A. Koch photograph collection of India,

South Asia, and Australia, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Samuel Bourne, “Varanasi (formerly Benares), Vishnu temples on the Ganges” (1866) (photo courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

Bourne & Shepherd, “Delhi, His Eminence, The Viceroy’s Elephant, Delhi Durbar” (1877) (photo courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

Bourne & Shepherd, “Darjeeling, The loop on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway” (c. 1880) (photo courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

Samuel Bourne, “Agra, The interiors of the Moti Masjid” (c. 1860) (photo courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

Samuel Bourne, “Delhi, Safdarjung’s Mausoleum” (1865) (photo courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

Samuel Bourne, “Delhi, The Great Arch and the Iron Pillar at the Qutub Minar” (c.1860) (photo courtesy MAP / Tasveer)

![Henri Rousseau, “The Snake Charmer” (1907), oil on canvas (Paris, musée d’Orsay © RMN-Grand Palais [musée d'Orsay] / Hervé Lewandowski)](https://hyperallergic.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Henri-Rousseau-Snake-Charmer-1907.jpg)