Visual Culture

What Art History Can Tell Us about Female Beauty Ideals

Imagine—as you probably do now and again—that you are God, laboring under the self-appointed task of creating an Eve who will be accounted beautiful at all times and places. History shows you will be disappointed in your effort. Rather than a stable set of features, physical beauty is an ever-morphing construct, a fickle collective dream that we fall into once in a while.

But as slippery as our fleshly aspirations may be, they tend nevertheless to have outlines. These have been most visible throughout history in the pictures drawn by those self-elected gods we call artists. History provides us a record, and from it one basic, inescapable, and ultimately unconscionable truth stands out: the ideals women are asked to embody, regardless of culture or continent, have been hammered out almost exclusively by men. This fact, more than any sort of evolutionary determinism, has meant that a fairly narrow range of attributes resurfaces across eras, returning every couple of decades or so like a new strain of the flu.

Physical ideals are changeable, manifestations of the cultures they come from, yet some aspects change more readily than others. Even when produced by those of their own gender, images of women have historically followed a pattern set down by males. Little about

’sSleeping Venus (1625-1630), for example, suggests its female maker. In it, as in virtually all pictures of women, passivity is the norm, whether manifested as softness, slack musculature, or a deferential pose. Another abiding trait, the outline of the hourglass, reminds us that the Female is always a sort of clock, which we try to freeze at the moment of youth.

Left: Aphrodite of Knidos, Ludovisi Collection. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, via Wikimedia Commons. Right: Photo by @amaliaulman, via Instagram.

Still, in recent years the forces shaping ideals of feminine physical beauty have shifted markedly. The most notable of them is that, as part of a more general democratization of image consumption and production, women themselves began redefining the ideals to which they aspire. This means that many more notions of beauty are now available. Consider, for instance, the ways that figure shaping has altered over the centuries. Some 150 years ago, women in Europe began wearing bustles beneath their dresses that greatly enlarged the profile of their buttocks. The bustle had replaced hoop stays, which had produced an inverted-goblet figure.

More recently, the notion of sculpting has been applied directly to the body. In the 1960s, it took the form of dieting, which produced the sort of extremely skinny figure we associate with such models as Twiggy. Her thinness connoted vitality, an escape from the matronhood idealized by earlier generations, as well as an innocent, insouciant sexuality that was not dissimilar to a Roman-era depiction of the Three Graces. Consumerism, of which diet fads are certainly a part, has significantly expanded the range of off-the-shelf options for bodily enhancement. In the 1980s and ’90s, women frequently turned to surgery—breast or buttocks augmentation, nose jobs—and other non-surgical interventions (Botox, tanning).

It bears noting that if art holds a mirror up to culture, it has with rare exception failed to reflect a manifestation of female beauty of the last decade, one imagined into being by women themselves: the high-performance, muscled athlete. Popular magazines like ESPN The Magazine’s “Body Issue” have made gestures in this direction, by putting women like Serena Williams on the cover. But, in large part, art seems not to have taken account of the fact that the athlete has become a figure of everyday life, not just a pro.

However, if the following tour tells us anything it is that resistance is futile: we as a society, be it global or national, will always concoct versions of perfection—and aspire to remake ourselves in their image.

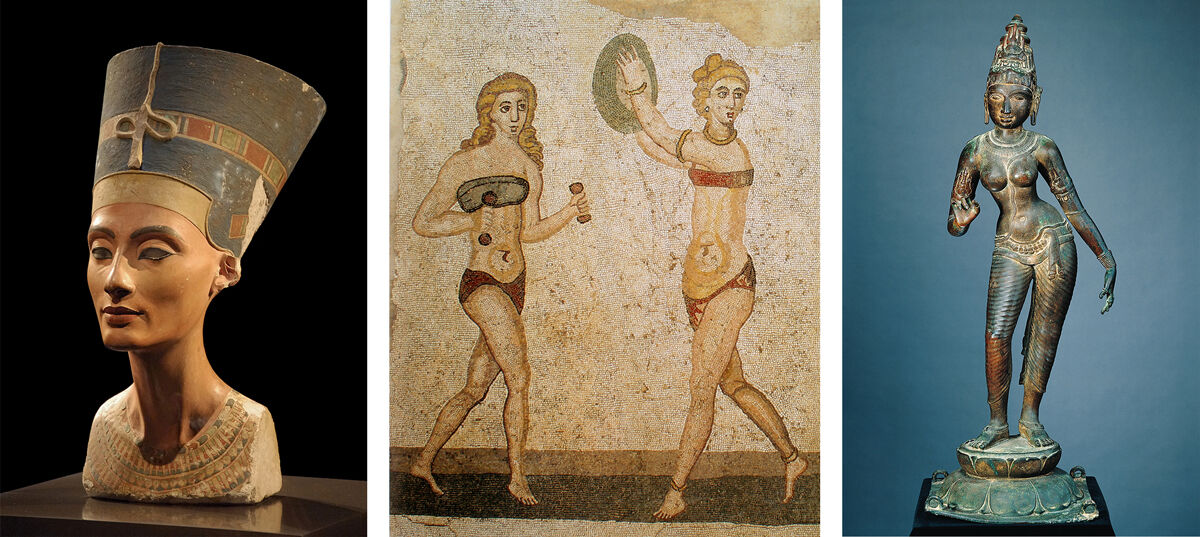

Left: Picture of the Nefertiti bust in Neues Museum, Berlin. Photo by Philip Pikart, via Wikimedia Commons; Center: Bikini girls mosaic, Villa del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Sicily, Italy. Photo by Yann Forget, via Wikimedia Commons; Right: Parvati. India, Tamil Nadu. Chola period, 11th century. Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, Asia Society, New York. Photo courtesy of Asia Society.

Egypt, New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, Queen Nefertiti, ca. 1350 B.C.

The kohl around Nefertiti’s eyes and her apparently rouged lips speak to a desire for enhancement and adornment that seems too much a part of being human to have a historical starting point. Trends in altering how we look through fashion and jewelry in all likelihood predates any culture-wide preference for a specific body type. The Egyptian example has proven especially influential in the West, particularly since the 1920s.

Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Knidos, ca. 350 B.C.

Originally carved by the Greek sculptor around 350 B.C., the Aphrodite exists only in copies. Of which there were many, because this Aphrodite represented the embodiment of female beauty for Classical Greeks. For us, she is the original Western model, woman as goddess, to be adored and feared. Her soft, rounded flesh bespeaks the power of her sexuality and advertises her life-giving potential.

Bikini Girls, A.D. 4th century

Part of a mosaic found in the early 4th-century Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily, the “Bikini Girls,” as they are known, provide one of the few celebrations of the female figure performing athletic acts, other than dance, in the history of art. Thin without being wrought by exercise, their vivacious bodies would not be out of place in mid-20th century Italy or America. Which is to say, the present a “natural” ideal, formed by activity rather than training.

India, Tamil Nadu, Chola period, Parvati, early 11th century

Consort of Shiva, Parvati is typically endowed with wide hips, ample breasts, and full lips. But, though hers is a more overt sensuality than the Western Venus, it is also not leisurely; her physique is not padded. She is active, essentially a dancer, with condign grace and strength.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Les Trois Grâces (The Three Graces), 1531

A theme from classical mythology, The Three Graces explicitly represented the ideal of feminine beauty. What that meant in the northern Renaissance was women of leisure—and little exercise—with thin, sinuous, and softly rounded physiques. Although these women bodied forth sensuousness, their figures, with relatively small breasts and depilated pubis, seem almost unsexed.

François Boucher, The Bath of Venus, 1751

The mythological trappings here are mostly a pretext. Formed by leisure—abundant food and non-strenuous recreation resulting in generous curves—the ideal body is characterized by its colors. Blushing cheeks, red lips, and pearly skin at once indicate vitality and ornament the flesh, hinting at a playful sexuality.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Night (La Nuit), 1883

Far more than the avant-garde Impressionists, the salon-painter reflects the middle-class tastes of late 19th-century Europe. Woman here is allegorized as Night, a somewhat tamed temptress—her shorn pubic hair reflects prudishness rather than fashion, while her ample, hour-glass figure suggests fecundity as much as sexuality.

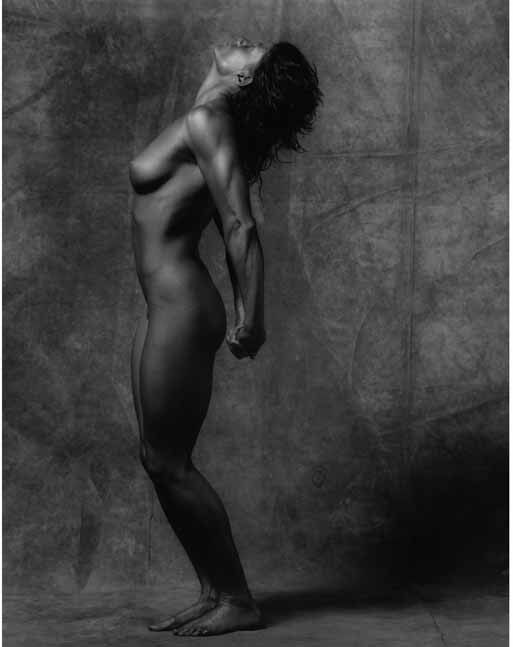

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon, 1981

When turned his lens on the winner of the first Women’s World Pro Bodybuilding Championship, in 1979, Lyon was considered wildly muscular for a woman. Today she wouldn’t stand out at your local gym. Yet, while she is presented as an exemplar of beauty, her musculature is a static enhancement, carved out like a statue, rather than something to be energetically employed.

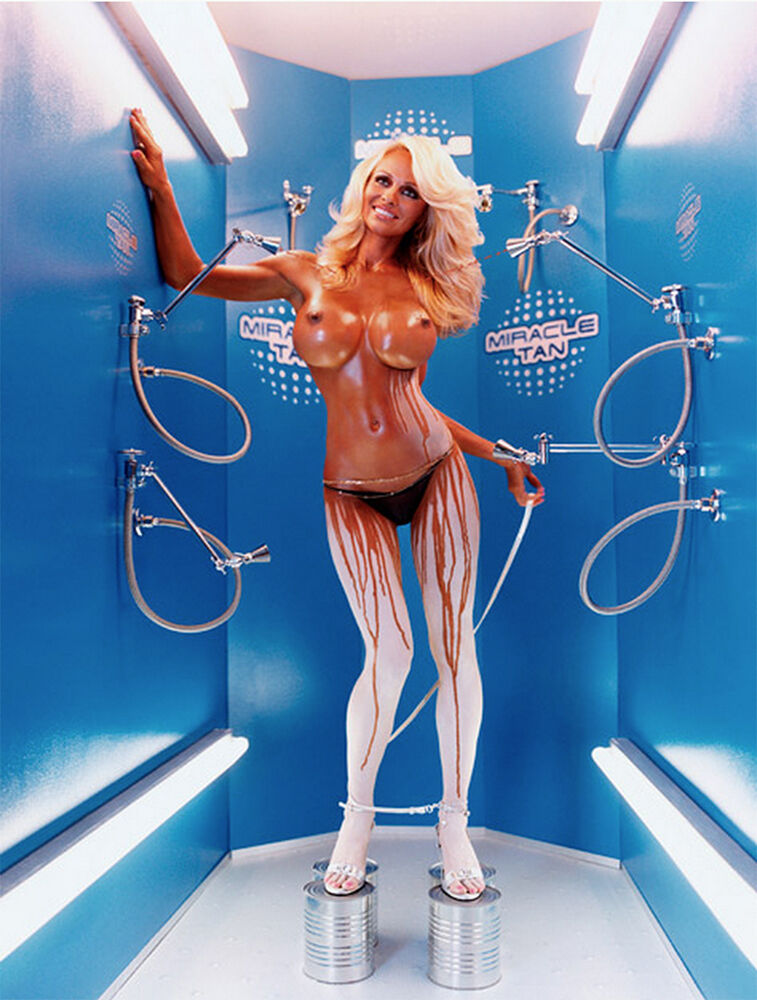

David LaChapelle, Pamela Anderson: Miracle Tan, 2004

As the title suggests, Anderson’s is not a sun-tan but rather a spray- or bed-tan—purchased, not pursued in the outdoors. Such technological enhancements promise nothing short of the miraculous: her pumped-up breasts, machine-toned arms, and airbrushed skin all aim, in LaChapelle’s lens, to show that nature is but a poor imitation of artifice.

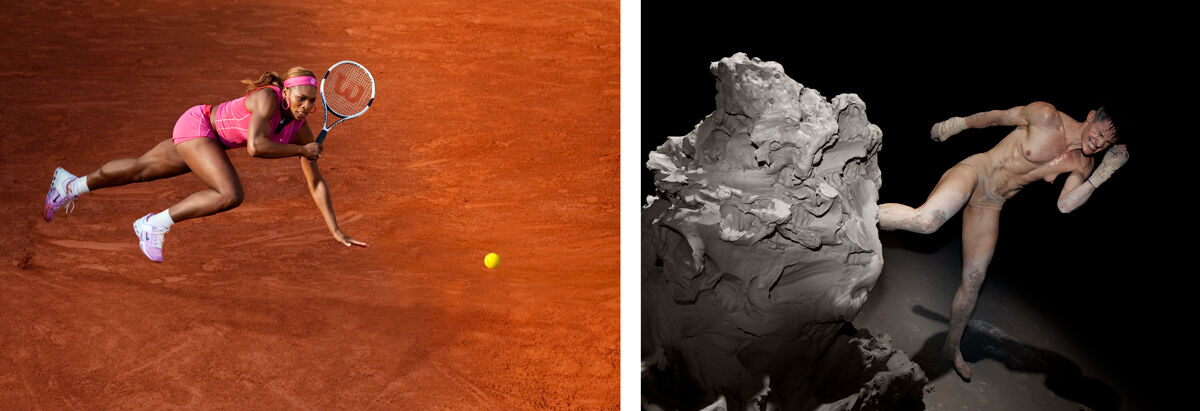

Bob Martin, Serena, 2004

More than any other woman, the tennis player Serena Williams has challenged—and redefined—norms of the female physique, allowing bigger bodies and developed muscles to compete in the aesthetic arena with the ideal of skinniness. Equally important: Williams’s muscles tend to be portrayed as built by and for athletic acts, not body sculpting.

Left: Bob Martin, Serena, 2004. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum. Right: Cassils, Becoming An Image Performance Still No. 4 (National Theater Studio, SPILL Festival, London), 2013, c-print 22 x 30 inches edition of 5 photo: Cassils with Manuel Vason. Courtesy of the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

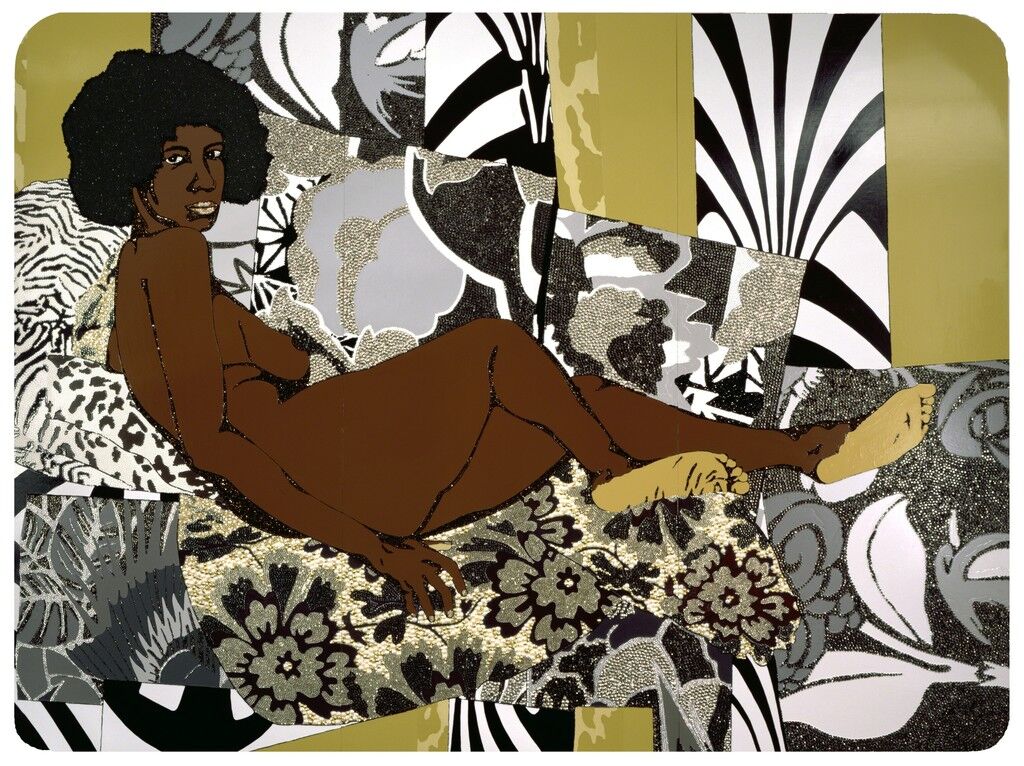

Mickalene Thomas, A Little Taste Outside of Love, 2007

A contemporary version of the odalisque (which in art history has come to refer to almost any nude female reclining on her side but which, as in the title here, can also refer to a paramour). Sporting a “natural,” she recasts the artistic tradition’s most sophisticated sex object as a woman of African heritage.

’s image exemplifies a recent embrace of a historically wider variety of female shapes—for instance, broad hips, a bigger booty, stronger thighs—as well as racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Cassils, Becoming An Image Performance Still No. 4 (National Theater Studio, SPILL Festival, London), 2013

is one of the few contemporary artists to explore the aesthetic appeal of muscle, emphasizing its functional power. Here Cassils explicitly opposes a powerful body with raw clay: the artist performs, instead of posing. But, by questioning gender barriers as a trans artist, Cassils leaves stereotypes of female muscularity unchallenged.

Amalia Ulman, Instagram post (2014)

The mirror reflects not only social expectations for a young woman’s selfie—the thrust-out bottom, lingerie clinging to a thin, sporty figure—but also the power of her role playing. What has changed in the contemporary era is less her yoga-strung physique than the fact that she presents it for herself foremost and then allows the viewer access to her performance.

Daniel Kunitz

No comments:

Post a Comment