Molly Soda on How Social Media Changes Us IRL

Over the past few years, Molly Soda has put her private life online, for the sake of excavating and exposing the archetypal young person’s internet experience. The artist has filled solo shows at galleries from L.A. to London with YouTube videos, screencap selfie collages, GIFs, and ’zines, all featuring herself—or at least some version of herself. She’s among a growing group of artists, like Maggie Lee and Amalia Ulman, who’ve adopted online platforms in their practices, as mediums to foster digital alter-egos or consider identity on the internet.

Molly Soda’s real name is actually Amalia Soto, but it’s her pseudonym that has developed an impassioned following (68,500 Instagram followers, and 35,500 via Twitter). She’s developed this online persona to such a complex, dynamic degree that her audience (online and IRL) has often confused Soda and Soto. Now, with her debut New York solo show, she’s trying to set the record straight, while also making her audience consider their own digital identities.

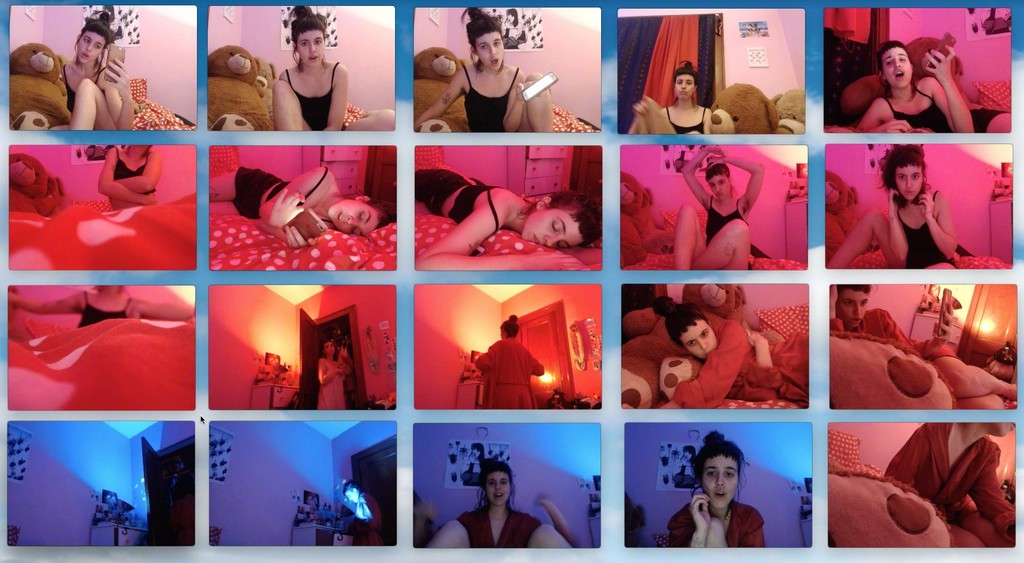

Installation view of “Molly Soda: I'm just happy to be here” at 315 Gallery, Brooklyn, New York. Courtesy of the artist and 315 Gallery.

Installation view of “Molly Soda: I'm just happy to be here” at 315 Gallery, Brooklyn, New York. Courtesy of the artist and 315 Gallery.

“It’s sort of a rebuttal to the way that people perceive my work,” Soda tells me as we walk through the show, titled “I’m Just Happy to Be Here,” at 315 Gallery in Brooklyn. “People maybe perceive me as being really honest or sincere, and this is me being, like, ‘Well, that’s not real.’”

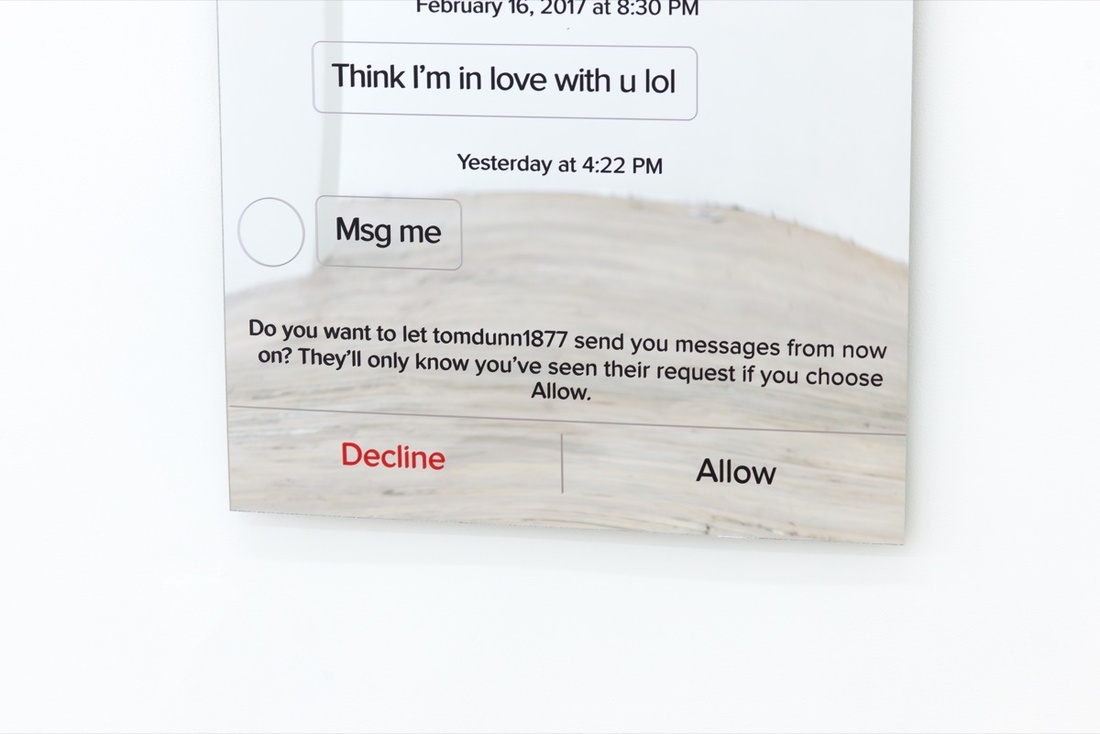

The show comprises mirrors printed with Instagram direct messages, lip-sync videos, an interactive laptop work, and GIFs that stream on iPhone 4s strewn across the gallery floor. (Why are they on the floor? “I like making people get into awkward positions,” Soda affirms.) “I’m Just Happy To Be Here” presents a multitude of Mollys. There’s a Molly with the proverbial angel and devil (themselves mini-Mollys) perched on her shoulders; Molly as a cowgirl, singing karaoke; Molly as a clown in the woods.

Soda taps into a tension familiar to anyone who has ever used the internet: the inevitable discrepancy between the way we’re perceived online (through the personal brands we craft) and the way we actually are in real life. Online, Molly Soda wears black eyeliner and sparkly eyeshadow; her hair is curled or coiffed or streaked with purple (or yellow or blue). Alone in her bedroom, she feeds off of her followers, spending hours singing and dancing, giving makeup tutorials, and making faces, occasionally wearing little clothing.

Like Soda, Amalia Soto is obsessed with the internet and loves karaoke, but the similarities seem to dwindle from there. When we meet at the gallery she’s wearing an oversize sweater, a long gingham dress, clunky boots, and no makeup. She speaks matter-of-factly about the state of the internet (“it’s never felt more tense”); the burner Instagram account she keeps to follow her friends; her take on #covfefe (“I love conspiracy theories”); and her desire to start keeping a physical diary. She’s not the person she plays online.

Some eight years since first creating the screen name Molly Soda on Tumblr, the artist is often asked by new friends and acquaintances, most of whom first “met” her online, which name she goes by. “I don’t really care either way, as long as you know that Soda is not my last name,” she replies. “But that’s just also the power of the internet, and the way that we get to know each other now.”

Detail of Molly Soda, Bored, WYD?, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and 315 Gallery.

Detail of Molly Soda, Bored, WYD?, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and 315 Gallery.

Soda is a digital native, part of a generation that came of age online. Born in 1989, and raised in Bloomington, Indiana, she cut her teeth blogging on Xanga, then moved to LiveJournal, racking up a cache of daily entries that chronicled her teenage life (topics included hanging out with her boyfriend and learning to drive). Many of her friends today are people she first met online; her current Brooklyn roommate, for instance, is a mutual friend she met through Xanga.

As Xanga and LiveJournal fell out of vogue in the early aughts, she turned to Tumblr in 2009, while studying photography at NYU. She wouldn’t consider her work art until later, but during this time, as her posts became more visual and less personal, the Molly Soda persona began to take shape.

She notes that today, with Instagram and Twitter—the two platforms she considers most consequential—the focus on personal branding is inevitable. “With Tumblr, you didn’t have to post any pictures of yourself, nobody had to know anything about you, people just liked your taste in things or the way that you curated a sort of mood board,” Soda recalls. “Now, it’s very much like you have to love me, my identity, and it all rides on people literally validating that.”

Validation is central to Molly Soda’s persona, and the work that she creates. Particularly resonant in the new show is That’s Me In The Corner (2017), a video of Soda singing alone in a private Koreatown karaoke room that she streamed live on Instagram. Disco lights stream across her face as she earnestly works her way through a half-hour-long playlist including “Stay” by Rihanna, “Otherside” by Red Hot Chili Peppers, and “Losing My Religion” by R.E.M. (she borrowed its lyrics for the work’s title). While somewhat light-hearted at first blush, the video takes on a sinister tone.

The number of viewers watching the live video drops from over 100 to hovering around 20 or 30; Soda’s wide eyes stare longingly at the screen, lighting up momentarily when her followers write fawning comments. The piece conveys the common sensation of posting something online and feeling waves of disappointment, delight, or validation, depending on the likes, retweets, replies, and comments.

Installation view of “I'm just happy to be here.” Courtesy of the artist and 315 Gallery.

Installation view of “I'm just happy to be here.” Courtesy of the artist and 315 Gallery.

Soda’s practice is also driven by a desire to archive her online interactions for posterity, and as potential fodder for future works. (One 2012 work, Inbox Full, was an 10-hour-long video of herself reading off all of the messages she’d received on Tumblr.) She’s also keen to preserve the different visual iterations of the internet. She fears a hypothetical scenario in which she wakes up to find that Instagram no longer exists. “I’m so terrified,” she says, “Not that I need Instagram, but I need to have had all of that stuff saved.”

Soda is adamant that the internet will always play a central role in her art, which will itself be readily accessible online. But she’s currently questioning to what extent she herself will figure into her future work. She acknowledges that 14 years of a diaristic practice has taken a toll—as have the demands of the online community itself. “I feel like a lot of the work I make ends up being kind of sad or dark because that’s how the internet feels,” she explains. “I love the internet, and I have grown to care about it so much—but it’s a complicated relationship.”

—Casey Lesser